To sulphurous and tormenting flames

In my last post, I wrote about my great plan to get to an outcrop of Bland monzonite. This is a formation important enough in the history of the Jemez that it really needs a place in the book, but it’s proven elusive. The main outcropping (map), which was mined for gold from about 1890 to 1930, is on private land that is very difficult to get to; there are two roads in and both are completely washed out. There is another exposure west of Crager Ridge (map) that is on National Forest land, but I have attempted every promising approach from north, east, or south and found that they all cross posted private land. After finding a good map of land jurisdictions, I settled on driving to the top of the ridge to the west (map) and then hiking down the crest of the ridge to the outcrop.

This looked like a difficult enough bushwack that I was disinclined to attempt it without a couple of companions. Some potential hiking partners found they had conflicts, but Steve Painter, a friend who retired from LANL recently (and has been enjoying his retirement altogether too much!) was available and I decided to try it with a single hiking partner. So Friday morning I took care of a few errands and then Steve picked me up and we headed out.

Sure enough, when we got to the turnoff (map) to the forest road leading to the ridge, we found the gate still locked for the winter (with not one but two padlocks. I guess they mean business.) Well, shucks and other comments.

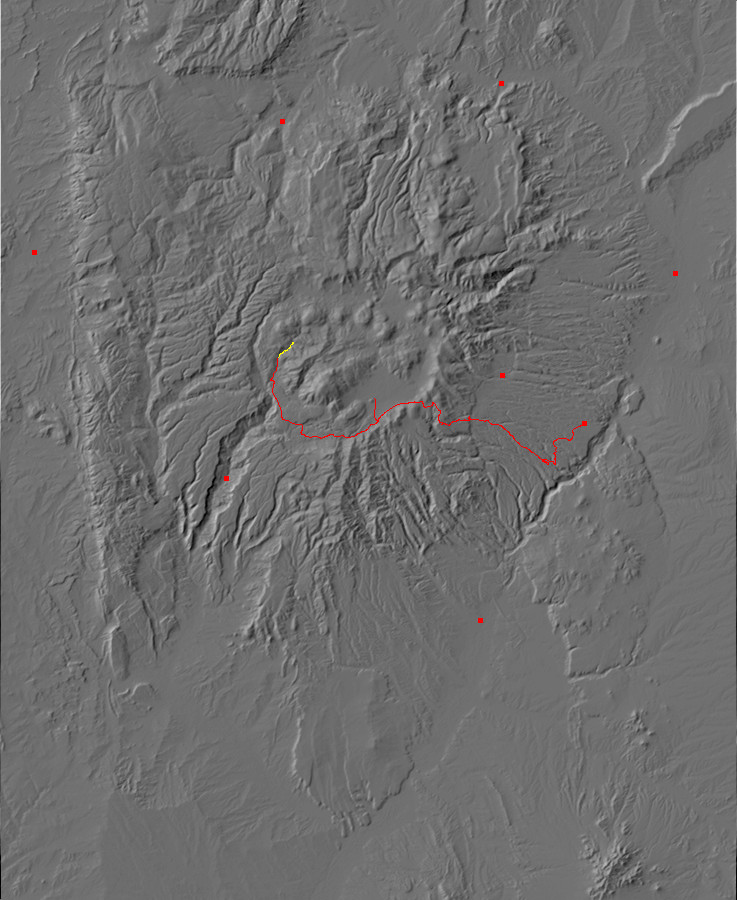

Plan B was to hike to the Redondo graben. This would require a Valles Preserve back country permit to let us drive to the trailhead (map). Alas, we found that we were a day too early; they would not start issuing back country permits until the next day. Well, what about hiking to El Cajete? Four miles each way; too much for the time available. But the rangers suggested we could hike through Sulfur Springs (map) to Alamo Canyon (map). So that’s what we did. (And, after some reflection, I decided to buy an annual pass rather than a short-term pass, as a show of optimism that my surgery will go well enough to let me get my money’s worth out of it.)

Since by now we were working on Plan D, I had not reconnoitered the area and had no map, geologic or otherwise. So we would be almost entirely winging it. We turned on what I guessed was the right side road (map); this petered out in an area of private housing. Steve allowed as how the next side road (map) looked more promising, and he was right. (We resisted the temptation to turn down a side road with a big sign and arrow saying “Freelove” [map]. Turns out this was just the name of the side canyon.)

We had been told at the Valles headquarters that we would have to hop over a couple of fences, but it was all right, really; so when we got to the first locked gate, with a big “VC” on it (map?), we parked, hoisted our packs and climbed over. There was a metal boxed guest register; I signed it for us.

We hiked along the forest road, which ran through a fairly steep canyon forested with conifers. There were occasional outcrops of volcanic rock on either side of hte trail, which I looked up when I got home and identified as Redondo Creek Rhyolite. About 1.2 million years ago, the Valles event erupted the Bandelier Tuff that forms the finger mesas of the Los Alamos area, and the magma chamber collapsed to form the Valles caldera. Fresh magma was injected into the magma chamber within a few tens of thousands of years, pushing the caldera floor back up to form a resurgent dome. Redondo Peak (map) and Redondo Border (map) are the most prominent parts of this dome today. The resurgent dome was full of fissures, through which relatively small volumes of silica-rich magma erupted to form the Deer Canyon Rhyolite and Redondo Creek Rhyolite. Most of the canyon walls along the first part of our hike are underlain by Redondo Creek Rhyolite.

We soon arrived at Sulfur Springs (map).

Sulfur Springs is one of the most geothermally active areas of the Jemez, which was once mined for sulfur and later developed as a hot springs resort. The resort failed during the Great Depression, and now all that is left are the old buildings of the resort, abandoned trailers, and the Detroitus visible in the second frame.

The area immediately around the springs is underlain by Deer Canyon Rhyolite tuffs, but these have been altered to light clay minerals by the hydrothermal activity in the area. The smell of sulfur is unmistakable.

We hiked on, though not without pausing to take in the amenities

the scenic views

and the utilities (map).

Steve concurred that we would not be sampling the local water supply.

Still, the surrounding area is beautiful (map).

This is Sulfur Point, a possible eruptive center of the San Antonio Member of the Valles Rhyolite. This was lava erupted through the ring fracture that formed when the Valles magma chamber collapsed. This eruption took place about 557,000 years ago.

Because there is obviously hot rock not far below the surface here, exploratory geothermal drilling was done in the area during the 1980s. Steve spotted one of the well pads not far from the road, which turned out to be the Baca #1 well (map).

The geothermal potential turned out not to be great enough for profitable exploitation, but the drilling contributed significantly to our understanding of the geology of the Valles caldera.

Another view of Sulfur Point.

The trail closed up again and passed some impressive stacks of Redondo Creek Rhyolite (map).

The yellowish discoloration towards the bottom indicates that hydrothermal alteration has taken place. Typical alteration minerals here are alunite and jarosite, which are insoluble sulfate minerals.

Soon we reached the mouth of Alamo Canyon (map), where there is another area of hot springs.

We hiked a short distance up Alamo Canyon, which is a beautiful area. This would be our lunch break.

Alamo Canyon is a medial graben on the resurgent dome. The floor of the canyon has dropped along faults in the north and south walls, produced as the surface of the dome stretched as it was pushed upwards.

After lunch, Steve and I explored the nearby springs. This was a rocky area with bubbles emerging from several places. In some cases, there was what appeared to be sulfur deposits around the springs.

It is hard to imagine that this is anything but sulfur deposited by the spring. However, when Steve boldly put a finger into one of the bubbling vents, he found that the water was icy cold. We tried several vents; only one was lukewarm rather than cold. I tried tasting the water on my finger (from sticking it in a spring vent.) There was no noticeable taste. We speculated that the hot springs had been diluted by heavy spring runoff.

We headed back, and on the way I took one more picture of a lava stack

And my Ansel Adams moment for the day.

Passing back through Sulfur Springs, we decided to look around a bit more. Here is one of the old bath houses; judging from the map, this may be Kidney and Stomach Trouble Spring.

(I assume that means the waters are supposed to cure your kidney and stomach troubles, not that they are supposed to give you kidney and stomach troubles.)

We also inspected the Detroitus, and found that one of the cars was a Toyota and probably dates back to the 1980s geothermal exploration. The others appeared to be considerably older, perhaps dating back as far as the 1930s resort.

West of the resort is a bank of heavily hydrothermally altered Deer Canyon Rhyolite tuff.

We headed on out and home.

Steve has expressed interest in taking another crack at the Bland monzonite once the gate is open. That probably won’t be until the fall dry season, since my shoulder needs time to heal, and I don’t want to be climbing down the crest of that ridge during thunderstorm season. Still; I definitely want to try again.

Shoulder update: Another appointment last Thursday, at which I discovered that my appointment had been misplaced. I have to give them credit; they squeezed me in and made sure I was actually on the surgical schedule for May 27. At least, I hope so; I got a message to call the surgeon’s office Friday, while I was off hiking, and I worry I’ll find when I call Monday that there has been some kind of delay. I want to get it over with.

I tried functioning with just one arm today, as an experiment. Among the things I found that I simply could not do were peeling an orange and testing my blood sugar. It’s hard to poke your finger and sample the blood one-handed. Cindy almost fainted when I told her she might have to help me; she does not like the thought of poking my finger for me. I found it is also hard to dress yourself (especially in buttoned clothing) and to open a child-proof pill bottle. Oh, and I can’t tie a tie one-handed; I’ll have to wear a fake bow tie to church.

I don’t know if I’ll slip in one more adventure next weekend, before the surgery. I’d like to join the LAGS on their trip to Magdalena, but that’s a long way to drive with my sore shoulder. A lot will depend on the weather, too, which looks miserable for as far ahead as the forecast shows.