The wanderlust gods, they taunt us: day 2

Day 1 may be found here.

After getting up at a decent hour, and confirming that little in the hotel’s continental breakfast selection was safe for a diabetic, Bruce and I headed out for a cup of alkaloids (in Bruce’s case) and some complex carbohydrates with fat and protein (in my case.) The breakfast venue was a quirky little cafe, the Java Moose, whose trademark is a trio of dancing moose looking vaguely like rock art Kokopelli. But friendly: The whole town oozed friendliness.

I got a cup of oatmeal, which turned out to have much more sugar than I really wanted. Fortunately, it had been cooked with plenty of water and had not been overcooked; I strained out and ate the oats and left most of the sugar in solution. Also a bagel with ham, cheese, and egg, of which I ate half and saved half for later. (This may have been a mistake.)

We headed back through Mosquito Pass to the Collegiate Peaks Overlook. Only then did I realize that I had left my camera and GPS in my car. (We were riding in Bruce’s car.) Well, shucks and other comments.

I had my cell phone. It can take pictures, though I have almost never done so, and was not quite sure how it worked. It looks like I have pictures on my phone, but I haven’t yet figured out how to get them onto the Internet.

It’s a shame, because we then visited a fairly cool Paleozoic outcropping sitting on Precambrian rocks, somewhere around here; the Great Discontinuity. The outcrop was a pretty limestone, the Ordovician Manitou Limestone, I think. I don’t recall that we saw any fossils to speak of.

From there, we drove through Antero Junction almost to Hartsel, a little town we would visit repeatedly. The road went past a number of saline ponds, for this is evaporite country. Much of this area is underlain by the Maroon Formation, which includes red beds and thick evaporite sequences. Evaporites are soluble minerals deposited by evaporation in a shallow briny sea; they include the obvious, halite or rock salt, but also gypsum and soluble potassium and magnesium minerals.

Just short of Hartsel, we turned north towards Garo, a very small ghost town. There are just a couple of buildings left, one of which is the old post office. Bruce had a book full of road logs for South Park, and one log took us through Garo and along dirt roads through a subdivision to a cluster of hills. The road log dryly commented that a developer had sold lots in this subdivision to Easterners on which it would have been nearly impossible to successfully build a house, because the underlying evaporites make the ground extremely unstable and prone to sinkholes. Numbers 16:32 comes to mind.

We were looking for a gypsum outcrop and I somehow had gotten the notion it was in a road cut, which were rather scarce hereabouts. We finally found ourselves on the side of a hill looking at what turned out to be andesite. Well, piss. Which we proceeded to do, though more out of relief than anger: We’re both men over 50 and it had been a while since our last stop.

Turns out the gypsum outcrop was supposed to be in a drainage ditch by the side of the road but I had missed that while reading the road log. I claim it was one of the very few significant navigational errors I made on this trip.

Back to Garo, and a stop at a hogback on the way back to Fairplay. Here, I think. Without my camera and GPS, I can’t show or tell, but the road cut had some nice red and white sandstones in it, probably of the Garo Formation. (Ya think?)

Back to Fairplay. Picked up my GPS and camera, and continued north along route 9. There was a nice road cut just north of town, exposing beds of the Pennsylvanian Minturn Formation.

The road log told us that the lower two-thirds of the section were fluvial and the upper third was marine deposits. The transition seems pretty clear here.

The fluvial portion appears to have rhizoliths.

Rhizoliths are a kind of fossil trace of roots. The roots themselves are not actually the fat structures visible here; the roots would have been much thinner, but because of their content of organic matter, they alter the rock chemistry in a zone around the root. In this case, the organic matter reduced the free oxygen content of the altered zone and converted the red ferric iron to soluble ferrous iron, which likely long ago leached away to leave the pale structures visible here.

In the other direction were large mounds of placer tailings from gold mining.

We turned around and headed back towards Mosquito Pass. We were on our way to visit a mutual acquaintance, Jorian Sartorius, who runs a supply company for emergency responders. After visiting Jorian, we would head off to the Mt. Aetna caldera following yet another road log.

Some more shale of the upper Minturn Formation:

From there through Mosquito Pass and down to Salida. Here we met with Jorian, who is chief technology officer of Rescue Essentials, friend of the Wanderlust, and an old acquaintance of both Bruce and me. We got a fascinating tour of the business, which specializes in tactical emergency medical supplies. We also saw Jorian’s collection of leg splints, which included models going back almost a century.

Jorian recommended a local pizza restaurant, Moonlight Pizza, which was indeed very good. I know: I’m a diabetic. I don’t eat pizza. Well, I did for lunch this day, just this one time. It was excellent, too. (The house salad was also pretty decent.)

We headed out of town, encountering some awfully tame wildlife along the way.

Bruce noted that this did not appear to be a terribly well-fed deer.

We headed back north, for the Mt. Aetna caldera, for which I had a road log. This was a truly enormous caldera that erupted some 35 million years ago or so, producing, among other things, the great Wall Mountain Tuff outflow sheet. Our log took us up Chalk Creek, and gave us a magnificent view of the Chalk Cliffs.

The gorgeous rock is the Mount Princeton Quartz Monzonite.

The gleaming white is plagioclase, the slightly pink grains are potassium feldspar, the gray patches are quartz, and the dark patches are muscovite and amphibole.

Further down, another wonderful view.

At left, an outthrust shoulder of Mount Antero. Chalk Canyon on the boundary of the first and second frame. Mount Princeton up the canyon in the last frame, with its foothills dominating the foreground.

The foothill at center is particularly interesting.

You may want to click to enlarge. (You can do this with almost all the pictures on this blog, if you haven’t already discovered.) There are what appear to be near-vertical black dikes in the outcrop. My road log did not mention this, and I don’t have a good enough geologic map to tell, but I wonder if this isn’t a shear zone associated with the caldera or its resurgence. I kind of wish we had thought to take a closer look — but the thing with road logs is, you tend to go with their flow.

Which took us up a canyon to the ghost town of Hancock.

Some more views of the area.

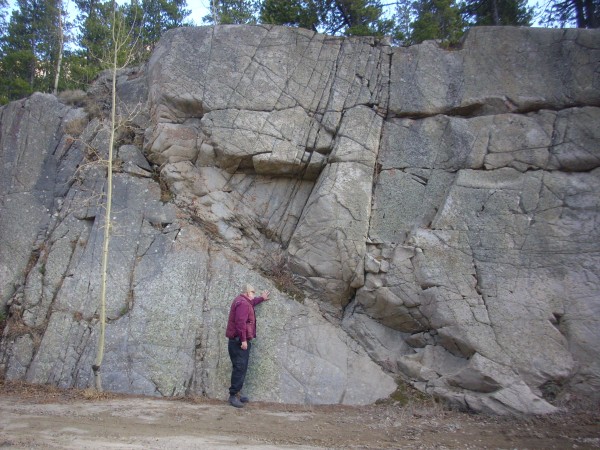

We headed back down the canyon, looking for a shear zone described in our road log. It took some time to find, but then it was obvious:

This marks an area of the caldera wall where part of the floor sheared past the wall.

Our road log next took us to a trailhead to look at more ring fracture zone features in the canyon wall. Alas, the trail was unclear, and we never found the features; but at least I got a nice picture from the trail.

We turned round and headed back. The road passes through the not-quite-ghost town of St. Elmo. It’s a historical mining town but there are actually still a few people living here. I was tickled to take some photographs.

The last photograph was in an area labeled “Chipmunk Crossing”. The bird is a Steller’s jay.

From here back to Fairplay to set up for the occultation. We ate at the Asian Fusion place again; this time I had beef and broccoli, and they were out of the hot and sour soup, so I had miso. Then we looked up a good location and time for the occultation; the ideal graze path passed right through the local high school football field, so that was a natural observing location, but the graze time was harder to get; we interpolated between Denver and Farmington, New Mexico, and came up with about 11:40. Then we sat around waiting for 11:40 to arrive, while anxiously watching the weather — which seemed to change every ten minutes.

Got to be around 11:20. I had my big 10″ Dobsonian telescope in my car; Bruce piled in, we set out, and I set up the scope. More anxiety; clouds periodically passed in front of the moon. But it cleared up just a few minutes before occultation time. I could see Aldebaran easily through the scope, slowly closing on the edge of the moon, and it seemed almost to be gliding in for a landing as the time approached … perhaps one minute to go …

And the clouds rolled in. And I felt a snowflake on my cheek. And:

Snow!

Except I didn’t say “Snow.” What I said is spelled with four letters and starts with S, but it is not actually the word “snow.”

Look, I don’t usually use colorful language. I think the example my parents gave me was that such language was almost never to be used, but I recall some extremely rare exceptions for very special occasions.

This was a very special occasion.

Bruce’s comments were even more colorful, as well as physiologically implausible.

We waited several more minutes, but it only got cloudier and the snow came down harder. The time of occultation passed. We packed up, headed back to the hotel, and turned in for the night rather unhappy.

Next installment: Bison, volcanics, and petrified wood.

Pingback: Great American Eclipse wanderlust, day 5 | Wanderlusting the Jemez