Great American Eclipse wanderlust, day 7

Day 6 may be found here.

Yesterday I visited the northeast part of the park, which I did not get to last time. Today my plan is to visit the south part of the park, for the same reason.

I had thought to climb Purple Mountain today, but my knee did not feel up to it. I started the day instead by driving through Firehole Canyon.

Firehole Canyon runs along the boundary between two large rhyolite flows within the Yellowstone Caldera. To the west, seen here, is the West Yellowstone Flow, one of the younger flows in the park. This came up against the older Nez Perce Flow to the east. Both were flows of dry high-silica lava, which is extremely viscous; vast quantities were erupted for the lava to reach so many miles from its vents. This kind of lava cools into a rock called rhyolite, which in many places in Yellowstone cooled so fast that the rock could not crystallize before solidifying and became obsidian.

The cliffs seen here show dark streaks where the flow encountered water, from streams or glaciers, and the water vapor rose through the partially solidified magma to rapidly cool part of the flow. The dark color is largely from small grains of obsidian.

Here is volcanic breccia possibly formed by steam explosions when the Nez Perce flow encountered glacial ice.

An even more striking example.

My camera had considerable difficulty locking onto GPS in the narrow canyon, so I don’t know the precise location. However, it was not far north of the falls:

As Bruce and I noted on the earlier trip, the sign here has a photograph of Hawaiian basalt eruptions, which are actually almost entirely unlike rhyolite eruptions. However, they’re a whole lot safer to photograph.

I continue down the road. In the distance is Twin Buttes.

Unfortunately, the far butte is hidden behind he near butte from this angle. These buttes are part of the rim of a very large hydrothermal explosion crater. Such craters form when something — perhaps nothing more than a drought — reduces the pressure on superheated groundwater, allowing it to explode into steam and carry away the rock above it. This would be a great place to hike to someday, but not this trip. The knee is feeling only slightly better this morning.

This stretch of road (Madison Junction to Upper Geyser Basin) is bestrewn with interesting hydrothermal features, and I’m pretty much wandering through all of them. This dead forest cannot be very old; there’s too much bark still on the trees. But sinter has whitened the base of the trunks and even grasses struggle to survive here. This patch of ground became heated relatively recently.

This illustrates the ever-shifting nature of the hydrothermal features. Sinter deposition closes old fractures in the underlying rock; earthquake activity opens new ones. One can also find patches of ground where the soil is whitened but many young trees have recently taken root; this is ground that has recently cooled off.

Silex Spring, if I’m not mistaken. (My GPS fix is slightly uncertain.)

This spring is quite hot, judging both from the copious steam and from the blue color. Orange and green thermophiles are restricted to the cooler edges of the pool.

The vent here emits a continuous load roar of rushing steam.

Clepsydra Geyser erupted just as I walked up; I didn’t quite get my camera up in time.

This one erupted for us last time as well.

I return to my car, continue south, and turn onto Firehole Lake Drive. Last time I was here, with Bruce, the road was literally melting from shifts in the hydrothermal activity, and it was closed shortly after our trip. (Not our fault, please.) The road has since been stabilized, repaired and reopened.

Another very hot spring, but with an impressive “runoff platform”, as one guide book calls it. This is covered with green and orange thermophiles.

This has an impressive sinter terrace around it. It’s also one of the more reliable large geysers in the park, erupting spectacularly every day or so. Still not as predictable as Old Faithful, but on my last trip with Bruce, a volunteer at the geyser had worked out the next eruption time fairly well, Bruce had a guidebook describing its behavior that allowed us to time the eruption to within a few minutes, and we were back just as the geyser went off. It was quite spectacular.

No such luck or preparation this time, but just the terrace is impressive.

I half-expected Charon to come rowing up with eyes like hollow furnaces of fire. Had not brought an obol to pay him.

I drove past Midway Geyser Basin; it was a madhouse and my experience was that you can’t properly appreciate Grand Prismatic Spring from ground level. I was headed to a trailhead where there is a bridge across the Firehole River.

The trail takes you to a low hill west of Grand Prismatic Spring, where you get a marvelous view.

Regrettably, it seems my first shot was with the camera accidentally bumped into the “bridal soft focus” setting.

But the panorama was set right.

Some beds in the hill across the way caught my eye.

I know: “You’ve got this in front of you, and you photograph that?” (Evil Kent, in best Bill Cosby Fatherhood voice: “Brain. Damaged. Geologists.”)

These are upwarped beds of the Mallard Lake resurgent dome. That makes them cool.

I head down to Biscuit Basin, which I do not remember from my last trip. The thermophiles are abundant here.

There is a ranger with a group of tourists; he seems to have some expert knowledge about thermophiles. The darker green in cooler parts of the springs are apparently filamentous cyanobacteria, large photosynthetic bacteria, and there are species of the mayfly, Ephemera, that have adapted to feeding off the cyanobacteria in hot springs.

The thermophiles color forests of sinter spikes.

(Try saying that three times quickly.)

My, I’m full of cheery classical references today, aren’t I? Which reminds me: I’ve been meaning to get hold of a copy of Dorothy Sayers’ translation of Inferno. Sayers was one of the Inklings, C.S.Lewis and J.R.R.Tolkien’s merry band of Christian humanists, notwithstanding a rather irregular personal life (including at least one illegitimate son). Her translation of Inferno is not particularly literal but is claimed by some critics to be truer to the spirit of Dante than many other translations. I don’t recall which one I studied in college; Ciardi, perhaps? I looked but can’t find my copy. (Evil Kent: “Inferno Lost?”)

A very hot pool; its overflow must flow some distance before it cools enough even for the colorful thermophiles.

I reach the west end of the basin. There is a trail into the hills, and a marker: Mystic Falls, 1.1 miles. That doesn’t sound far and my knee merely feels awful. And there are people on the well-marked trail. I go for it.

Rather interesting rock outcropping.

This is part of the Upper Basin Member of the Central Plateau Rhyolite. It’s one of the older flows and, from its appearance here, appears to be a bit richer in iron than most. Erupted immediately after the caldera eruption, I speculate it represents residual magma from a zoned magma chamber where more iron-rich magma was located deeper in the chamber. We see this pattern in the Jemez back home.

I reach a lookout point where several other tourists have gathered. It seems Old Faithful is erupting.

The eruption is about ten minutes early, and it’s the shortest I’ve ever seen. I speculate aloud that early eruptions may be less vigorous, because the geyser hasn’t fully recharged. The other tourists look at me like I’m some kind of geologist.

Incidentally, the other two eruptions I saw were about ten minutes late. The mean time is around 70 minutes now, and the eruptions may be coming a bit less regularly. Pity.

Obsidian by the trail.

The trail is climbing the West Yellowstone flow. The Little Firehole River below me runs between this flow and the Summit Lake Flow to the south.

Please to not sit here.

Well worth the climb. Mallard Lake Dome at left, the southern part of Madison Plateau at right. Upper Geyser Basin just left of center.

The trail goes on (for a very long distance, since it’s part of the Continental Divide Trail), but I turn around here. This was, after all, an impromptu hike, albeit on a well-marked trail with many other tourists and my cell phone. (Coverage is not a problem this close to Old Faithful.)

On the way out, I pause at West Geyser.

If my recollection is correct, this is a relatively young feature whose appearance killed the trees in the background.

I drive past Upper Geyser Basin and towards the West Thumb. At the continental divide:

I am startled; one does not normally expect to find lily ponds at the top of a mountain pass, and I wonder if this was artificial. Apparently not; the lillies are Nuphar polysepala, the great yellow pond-lily, with an extensive range and adaptability to altitudes up to 10,000 feet. I’ll have to look for it in Ashley Pond back home when I’m next there.

Hydrothermally altered rock across the road:

Yellowstone gets its name from the Yellowstone River, whose gorge has many spectacular exposures of hydrothermally altered rock like this. Orange tends to mean hematite, but the yellow color is likely jarosite, a potassium-iron sulfate mineral formed when hot acidic water breaks down rock containing both elements.

I pull into a picnic area and consume my lunch. I can see that there is a deep valley to the west, and I hope to get a view of the Mallard Dome from this perspective; the extension graben on top should be clearly visible. It is, but only as glimpses through dense trees, not suitable for photographs. Darn. The extensional graben is a fault valley on the top of the dome that formed as it was pushed up; the analog back home is the Rendondo Creek valley between Redondo Peak and Redondo Border.

A little further on, the sign says “Shoshone Lake Overlook.” I drive past, reconsider, head back, and park. Another car pulls up alongside me, and who pops out but the two blonde college girls from the Mount Washburn trail? That, or the other half of the quadruplets …

There is not actually a view of the lake; just dense forest below. Shucks.

I continue on past West Thumb and take the road to the south entrance. This is new country to me. There’s not much to see until I reach Lewis Lake.

I didn’t really think about it at the time, but … a wave-tossed lake surface is not exactly ideal for a panorama of separate exposures. I’m deeply impressed Hugin (the panorama software package I use) did so good a job of fudging the frames together.

And it’s a lovely lake.

I’ve been to Hawaii four times now; somehow, I’ve made all those trips without ever visiting a black sand beach, that I can recall. I look down:

Different kind of black sand, of course. In Hawaii, it’s very fine basalt cinders. Here it’s very fine obsidian grains.

If I ever make it back to Hawaii, I want to hike to the green sand beach near South Point. It’s polished olivine granules there.

I park at Lewis Falls. There are some excellent exposures of the obsidian-rich Pitchstone Flow, Yellowstone’s youngest, here.

Lithophysae:

Devitrified nodules within the obsidian. Probably started as gas bubbles that became lined with crystals from fluids moving through the rock.

I walk out onto the bridge for just the right angle on the falls. About a hundred other tourists are trying to do the same, but we all manage to avoid getting cross at each other.

I drive out the south entrance; a unique experience in that I am passing from one national park, with its own passes and fees, directly into another, with its own passes and fees. Fortunately I have an all-parks annual pass. I go as far as I think my time will permit, which gives me a shot of the Grand Tetons to the south.

This is another area I’d like to visit. Alas, I doubt I will ever be back this way again.

I return to Yellowstone. The road follows Lewis Canyon, which is very scenic, but there is a distressing lack of safe pullouts. This is the best I can do.

This is Lava Creek Tuff, part of the outflow sheet from the last caldera eruption, over Lewis Canyon Rhyolite erupted immediately after the first caldera eruption. I can’t tell for sure, but I think the more gray outcrops towards the very bottom of the canyon are the Lewis Canyon Rhyolite.

I head towards Canyon Village, a part of the Grand Loop Road I haven’t yet done this trip. I decide to visit the Mud Volcano.

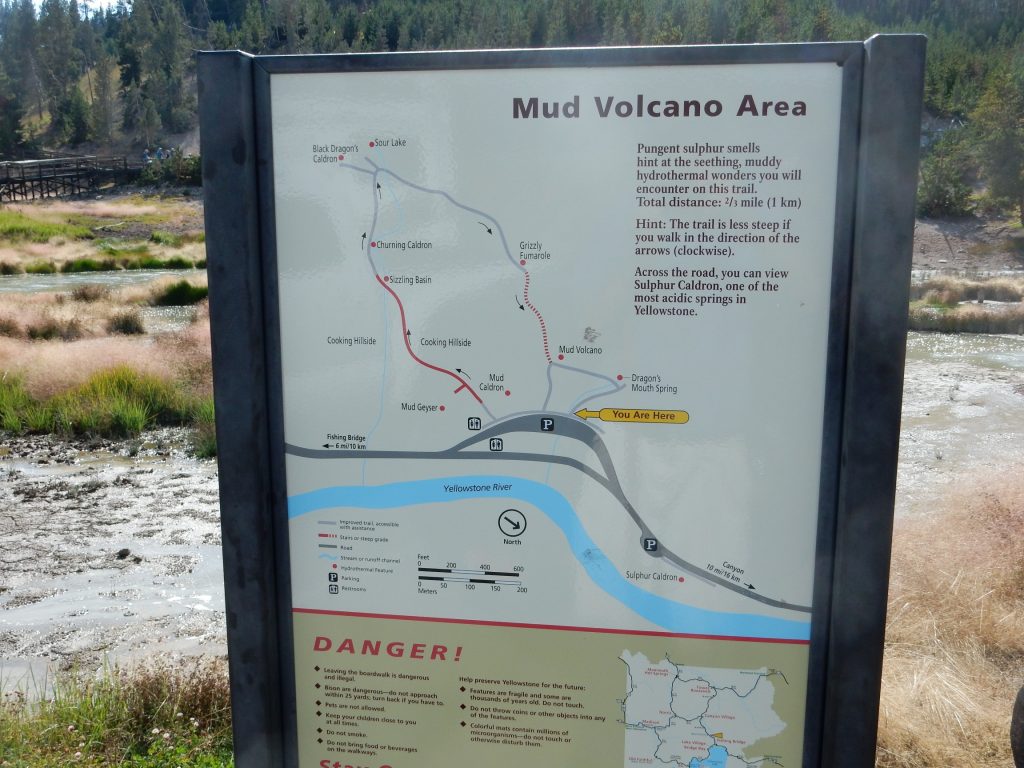

This sign amuses me.

“Hint: The trail is less steep if you walk it in the direction of the arrows (clockwise).”

Look, I’m not a mathematician, but …

Wait a minute. Yes I am.

It’s not mathematically possible for a trail to be steeper in one direction than the other.

Okay, okay. You think you know what they mean, and I think I know what you think they mean. Still.

I walk the path counterclockwise.

Mud flats crackling merrily away from rising gases.

It really does sound like there’s something bellowing back in there, with periodic waves washing out.

I don’t remember what this lake is called, but you can see several roiling spots on the water corresponding to underwater vents.

Nearby is Black Dragon Cauldron.

And a little further is Boiling Cauldron.

Most of the bubbling is carbon dioxide, not steam. This is one of the cooler features in the park (thermally, I mean. Well, not that it’s uncool geologically. … Never mind.)

An intriguing thing I first notice here is that the runoff from a lot of these vigorously bubbling springs is not that great. I wouldn’t estimate the runoff I saw in the channel from this spring at more than about a gallon a minute.

This hill is more notable than it looks.

This hill was heavily forested as recently as a few decades ago. The ground rather suddenly heated following a nearby earthquake, killing the trees. Now it looks like even the grass is starting to be burned off. Will a hydrothermal feature follow?

I continue on to the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. I find a parking spot on the south rim (no small accomplishment) then discover there is a trail to a lookout point, Point Sublime, further up the canyon. My knee is unhappy but I cannot resist.

A fine fat red squirrel. These guys have a remarkably loud chattering call. I heard it and got my camere zoomed in. This guy has a pine cone and he is working it over the same way Americans eat a cob of corn — holding it in his claws and rotating it as he worked down it from one end to the other. When he is done, he has a little nub of pine cone core that he tosses away. He grabs another pine cone, looks me over, and decides he’ll finish his supper elsewhere. Well, thanks a lot.

I come to a nice lookout point.

Yeah. The Grand Canyon of Yellowstone is one of those places where you almost can’t fail to take a spectacular photograph.

The geology is Upper Basin Member over glacier sediments in the nearby cliffs. Aways down the canyon, the brown color is Lamar River Formation.

I do a panorama.

Further down, a great shot up canyon.

The glistening spots on the canyon wall are probably cold springs.

My knee is hurting. I ask a couple of hikers going the other way how much further. “Not very far.” “Is it a great view?” “Meh.” Pride kicks in and I finish the hike anyway.

The hikers were right; the view isn’t that great and it’s now too late in the day for good photographs

I start back. At one point I pass a party of British hikers going the other way. A little further on, I find an older British woman sitting well back from the trail. “I lost my nerve” she explains, with cheerful candour.

At the trail head, I get a good view of the falls.

This shot needed to be early in the morning rather than early in the evening, alas.

I drive back to Upper Geyser Basin to recharge. I arrive just as Old Faithful geyser is going off.

Before recharging, I visit the grocery store here. As expected, prices are high. They are out of oranges. I do get some lunch meat, but there are no low-carb wraps. (That was a long shot anyway.) There is, however, some very fiber-rich bread from a local Montana bakery. I later discover that this is really excellent bread, and when I bring some home to Cindy, she laments that such bread cannot be found in New Mexico.

Dinner and turn in for the night.

Next: Elephant Back

Pingback: Great American Eclipse wanderlust, day 6 | Wanderlusting the Jemez

Pingback: Great American Eclipse wanderlust, day 8 | Wanderlusting the Jemez