A sedimental journey, day 8

Gary is scheduled to meet me at 8:30 and I arise in time for a good breakfast. Mom is already going through her morning routine.

Gary arrives and we repack the Wandermobile. I get a final shot of Mom.

We drop off Gary’s rental car, and then we’re on the road. We will be passing back through the mountainous spine of Utah, thrown up during the Laramide, and back onto the Colorado Plateau.

The first stop is in Spanish Fork Canyon near Greer Hollow. Looking north:

The cliffs are the Permian Diamond Creek Sandstone. This is likely beach sand from a time when the Pacific coast was located very close to what is now the mountainous spine. It would roughly correlate with the Cedar Mesa Sandstone we saw on the trip out.

In the other direction:

The cliffs are the lower Jurassic Nugget Sandstone. Between the two areas in the photograph are poorly exposed Triassic shales. The Nugget Sandstone covers the same age range as the Glen Canyon Group — the by-now familiar combination of Wingate, Kayenta, and Navajo Formations prominent further to the southeast.

We approach the Red Narrows.

This is mapped as the lower member of the North Horn Formation. This formation is a coarse conglomerate that straddles the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in geologic time and marks the climax of the Laramide orogeny in this area. The conglomerate was shed off the high mountains thrown up to the west.

A little further, it gets really red.

There is a convenient pullout for examing the formation more closely. To the north:

The notch is a less resistant bed insufficiently great in extent to be mapped.

Gary examines the rock with his hammer.

The clasts are a mixture of granitoid and volcanic rocks, the former predominating. All are well rounded but quite large. This suggests an alluvial fan. The red color suggests that the erosion of older red beds such as the Chinle contributed much of the finer sediment to the formation.

We examine a horizon of much larger boulders.

and the nearly clast-free red horizon.

Then we drive on to another spectacular road cut.

This is the delta facies of the Eocene Green River Formation. This formed in a huge freshwater lake, Lake Uinta, that covered much of southwest Wyoming, eastern Utah, and western Colorado. Here we are near what was the southwest shore of the lake, where delta mud alternates with freshwater limestone. Bird tracks can be found here, though we saw none.

A little further. We are between Heslington Canyon and Garner Canyon.

We pass Soldier Summit, where rock exposures are poor (the beds are easily eroded mudstone of the Colton Formation), and on the other side, we pause between Crandall Canyon and Sulfur Canyon to admire the new set of formations.

This is Price River Formation over Castlegate Sandstone, both upper Cretaceous. Further on we come to Castle Gate.

The mesa visible through the cut is Price River Formation over Castlegate Formation over Black Hawk Formation. All are Cretaceous. The road cut itself is in the Black Hawk Formation, which is beds of sandstone, shale, and coal. Two coal seams are visible at left, neither thick enough to be economically mined but both of high-quality coal. We spent some time here going over the beds, hoping to find some leaf impressions in the coal or adjoining shale beds.

But no great luck.

I picked up a big chunk of coal, and I find one dubious candidate for a leaf impression in the shale.

We head on to our first big planned destination, Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry. There is good signage proclaiming it OPEN that guide us to the access road, and there is signage along the road:

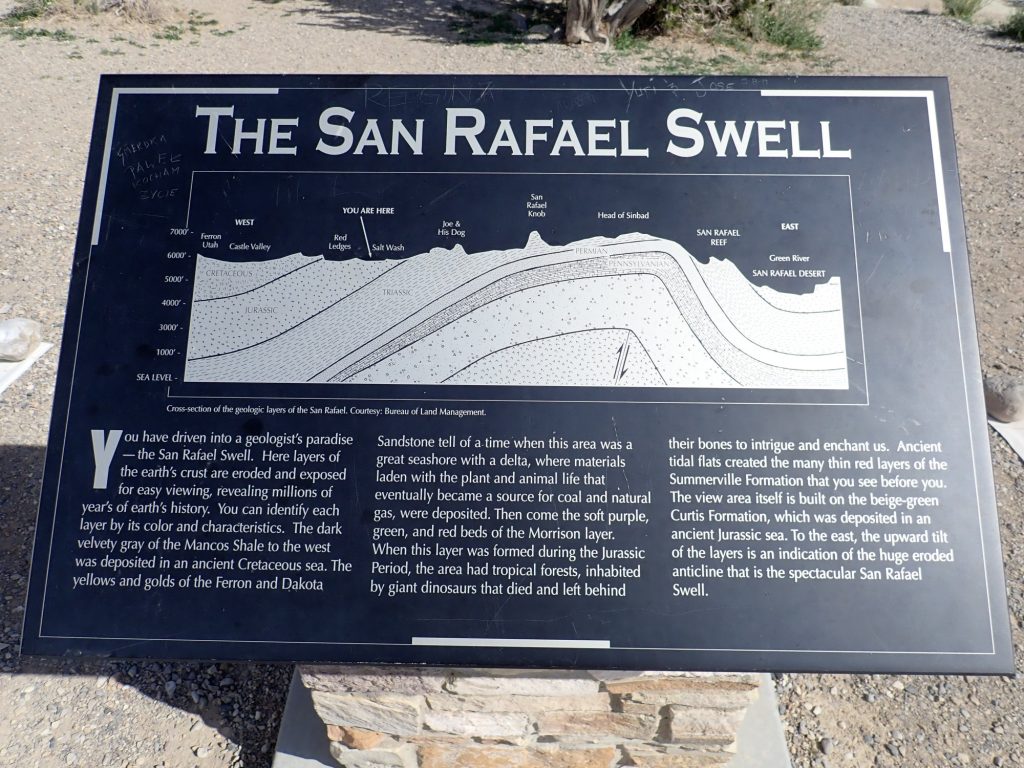

The road crosses the western boundary of the San Rafael Swell, a large upwarp in the earth’s crust sixty miles long and thirty wide. To enter the upward is to move backwards in geologic time. This begins here with the Blue Gate Member of the Mancos Shale, laid down in the Western Interior Seaway 80 million years ago.

Next comes the Ferron Member.

Yeah, we saw this last week near Capitol Reef. It marks a brief retreat of the sea. The resistant sandstone forms an escarpment.

Looking back northwest towards civilization. There is a thin strip of ground in the lee of the mountains and west of the San Rafael Rise that has enough irrigating water to support a string of small farming towns.

Next: the Tununk Member.

The Tununk is another shallow marine shale. The Cretaceous is notable for fossils of ammonites, nautilus relatives like the one pictured.

This looks like Dakota Formation to me and is at the same stratigraphic position. The geologic map I have identifies it as such. Naturita must be a local name. If so, this is beach sand from the Western Interior Seaway as it first drowned this area.

This is mostly mudstone, from coastal swamps and deltas preceding the Western Interior Seaway. Its equivalent back home is the Burro Canyon Formation, which is much coarser sediments.

Well, crep.

Closed and padlocked. Did we miss something? The signage seemed very clear.

(Checking after I get home, I see that the web site has the quarry closed this week. But there was no indications on the signs along the highway.)

We get out and wander around. Gary is inclined to jump the gate and just see what’s down the road. I take a few pictures.

Brushy Basin Member, Morrison Formation.

We walk as far as the Morrison Formation sign.

Dark desert pavement.

Unhappily we return to the car. The other road heads to something called Humbug Flats Lookout; but we never find that, either. The road appears to end near here at a set of trail heads.

Yeah, the cloud shadows kind of borked that one. But apparently we’re on Lucky Flats and, had we but known, we could have walked a couple hundred feet further south and found Humbug Overlook, which does indeed overlook a deep basin called Humbug Flats.

The ridge in shadows is all Salt Wash Sandstone Member, Morrison Formation.

We return to the main highway. Along the way, we see that CLOSED signs have been posted on all the quarry signposts that previously said OPEN. I’d swear they weren’t there driving in. And, considering that the quarry was open the day before (according to the Web site) I’ll bet they weren’t. We drove in just as someone drove out and put up the signs.

Crep.

Well, it gives me something to visit next time I’m in the area. Only, I’ll check the web page first for dates and times.

On the way out: Some hills capped with a sandstone layer. My wager is Ferron Member.

But it turns out this is the Poison Spring Bench, and it’s another gelogically young pediment surface over Blue Gate Member.

We drive south, planning to reprovision at one of the small towns. We pause on the outskirts of Huntington.

The prominent cliff is Blackhawk Formation over Star Point Sandstone. The lower bench is a pediment over Mancos Shale. The Blackhawk is here a coal-bearing formation, as it is back at Castle Gate, and the Huntington Power Plant is nearby.

Somewhere along here we stop to refuel. The gas station has a small pizza shop that also has shrimp baskets. I haven’t had a shrimp basket in years … When I get back out, Gary has struck up a conversation with a local woman (who, he later dryly notes, seems qualified to talk about food) who tells us there are much better alternatives down the road. We find a decent grocery store, reprovision, and have lunch at an adjoining Subway.

Just outside Ferron are some more gorgeous views.

Little Nelson Mountain. Also Blackhawk Formation over Sand Point Formation, with a small cap of Castlegate Sandstone and Masuk Member of the Mancos Shale at it feet.

You might think the Ferron Member must be nearby. It turns out that it’s east of town and does not form an obvious outcrop as seen from the highway. However, we do see the Emery Member north of Emery:

The sandstone beds with Blue Gate Shale Member beneath. Good spot for a panorama:

I like the little butte. She’s a beaut.

To the north is a bench covered with sand and alluvium.

On the skyline is Youngs Peak.

We arrive at the interstate just outside San Rafael Swell, and head east. Our first stop is as the road descends into the Ferron Sandstone Member.

Beneath is Tununk Shale Member. As on the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry road, as we go into the San Rafael Swell, we look at older and older beds.

To the east, the Mancos gives way to the Cedar Mesa and Dakota Formations as on the Cleveland-Lloyd Quarry road.

We see a viewpoint sign and decide it’s a good idea. The view area has signage.

And a view.

The white rock in the foreground is, as the sign says, Jurassic Curtis Formation. The great red valley beyond is all Entrada Formation, which is less resistant and so has eroded out. The lighter tan beds in the far distance are the underlying Carmel Formation.

Which we encounter in a road cut shortly thereafter, and find so pretty that we spend quite a bit of time here.

I guess from the stratigraphy that this is Carmel Formation. (I will be delighted to discover I’m right after I get home and check the geologic map.) This is a better outcrop than any I’ve ever seen; it’s thinner and less spectacular in the Arches area.

It has some beautiful ripple marked beds.

Smug Bed is Smug.

In the panorama, the lowest bed looks a lot like Navajo Sandstone; the map tends to confirm this. The layer above is the smug layer, which looks like shale and limestone with a lot of gypsum in it. Next comes a massive sandstone.

Above that is a really impressive gypsum bed, described as an alabaster gypsum in the geologic report.

This was really impressive. The lower part looks like limestone, which is perfectly sensible: gypsum forms from evaporation of ocean water, and when sea water evaporates, calcite is deposited before gypsum. (Salt follow next, but the evaporation here does not seem to have progressed that far; the overlying beds so no sign of the distortion you’d expect if salt had been deposited then dissolved out by groundwater.)

(I will learn after I get home that gypsum is heavily mined from the Carmel Formation in parts of the San Rafael Swell, accounting for two-thirds of Utah’s production.)

Above the gypsum is a tan sandstone.

I don’t know what the wavy pattern is. It’s not cross-bedding. I suspect it’s post-depositional in character.

To the east is San Rafael Knob.

This is an erosional remnant of Navajo Formation atop Kayenta Formation.

More monoliths in the distance.

I am a little surprised to see that the gypsum bed forms a break in the slope of hills.

That’s something I would have expected of a resistant bed, but gypsum is soft and soluble.

On into the Kayenta Formation. There are numerous erosional remnants of the overlying Navajo Formation.

Also here, near Ghost Rock.

We pass through a long section of Chinle and Moenkopi Formation, on the axis of the Swell, and enter a long roadcut in the Kaibab Limestone. This is the oldest formation we will see on this drive, being a Permian formation around 280 million years old. Beyond, the east limb of the Swell begins to dive steeply into the earth.

I had to scramble up the roadcut to take the panorama from a precarious perch. The zoom is from atop the median.

The lowermost yellowish-tan beds are Moenkopi Formation, with a cap of Sinbad Limestone Member. The lower reddish slopes of the mesas behind are upper Moekope Formation and Chinle Formation. Then come massive cliffs of Wingate Formation capped with thin beds of Kayenta Formation.

Then we’re back to the Navajo Sandstone forming the San Rafael Reef on the east side of the Swell.

The sun is getting low. I mentally recalibrate my plans to see Goblin Valley this evening; it will have to wait for morning.

Leaving the interstate, we take the road south to our camping area. The Reef is in shadow, but it will be beautiful in the morning. Our campsite is near Temple Mountain within the Reef.

We will pitch the tent atop the Moody Canyon Member of the Moenkopi Formation.

The view to the south is spectacular.

The lower beds are Moenkopi and Chinle Formations; then comes massive cliffs of Wingate Sandstone capped with Kayenta Formation.

We haven’t got a lot of hiking in yet, and there’s still some daylight. Gary has spotted what looks like mine shafts halfway up the mesa to the northeast. We decide to explore.

Ripple marks in Moenkopi Formation.

I don’t know what makes these different from those earlier in the Carmel Formation, at least not for sure. The Moenkopi was a tidal flat formation while Carmel was fluvial; it could be the difference between ripples in a river bottom from steady current and ripples from waves rocking back and forth.

Mesozoic ATV tire tracks.

My first impression was that this was unusual ripple marks in the beds. On reflection, I wonder if it might be a fossil impression, perhaps of tree bark Bruce, do you have any idea?

Temple Mountain ahead.

Temple Mountain is capped with Wingate Sandstone over the usual Chinle Formation and Moenkopi Formation. The foreground beds are Torrey Member of the Moenkopi Formation.

The middle beds, extending right from Temple Mountain, are Chinle Formation sandstone. The mine openings are visible just above and to the right of Gary’s head.

It’s a very steep scramble up the cliff.

There are bits of petrified wood in the sandstone. That’s likely how the mine formed: The reducing (oxygen-poor) environment from the decomposition of the organic matter helps precipitate metals from solution.

The adit level.

We’ve come a ways from the Wandermobile and our camp.

The adits (horizontal mine shafts) seem to me to very likely be old uranium mines, which also typically yield vanadium. (When I get back, I will find from mindat.org that I am correct.) However, they’re long closed and, in most cases, sealed.

Old mines are very dangerous. Sealing ones this close to an established camping area is the responsible thing. In the case of uranium mines, there is also the tendency for radon to accumulate, which is carcinogenic (though I wonder how badly from a brief exposure.)

More petrified wood. My guess is these mines exploit uranium substituting for wood in a point bar.

Some adits did not go back far.

There would be no reason to go further once you’d “lost” the vein.

We collect some bits of rock that seem to have a yellowish stain. I’m hoping it’s carnotite, and I’m under the impression it will fluoresce bright yellow-green under the UV lamp when we get home. (When I do, I find it hardly fluoresces at all. But then I check Wikipedia and find to my surprise that carnotite is not fluorescent. I suppose the next thing is to try a geiger counter, but I haven’t got one.)

These were not just prospects. Evidently substantial quantities of ore actually came out.

A shaft that could potentially be reopened.

Notice the marking at right”Bad air”. Probably radon.

Another sealed adit.

Claim memorial?

Citizens can stake mining claims on public lands with an affidavit that there are valuable mineral resources there. The claim number is recorded at the local land office and the claim must be marked. I’m wondering if this is such a marker.

Temple Mountain from back at camp.

You’ve probably noticed that our camp is next to a fenced area of ruined buildings. There is no signage but I’m guessing this is an old pioneer homestead. There is a trickle of water in the nearby arroyo, but what a place to try to settle!

The white patch of rock below the west (left) face of Temple Mountain is a solution breccia, a body of crushed rock that collapsed into an underground cave dissolved out of limestone beds not exposed at the surface. The limestone had petroleum in it, and the hydrocarbon vapors ascending through the crushed rock bleached it white.

We feast on pan-fried chicken. Gary goes to wash his hands and I discover that the twilight glow to the west lingers long after the sun has set. It is the zodiacal light, which is at its best evening presentation this time of year. When seen in the morning, it is sometimes called the false dawn.

Gary returns and we turn in for the night.

Next: An army of orcs