Christmas 2021

Fox is back.

This was a couple of weeks ago. We got just a dusting of snow that day, and Fox decided to take another day nap on our back porch.

Meanwhile, Stupid the Cat doesn’t understand why her bowl isn’t constantly overflowing.

Kitten is troubled by our inefficiency.

Last Friday (not Christmas Eve, the week before) Gary and I made another trip up to Ghost Ranch for Gretchen to teach us a little about fossil preparation. Filling up gas at Puye:

It’s a panorama I’ve done many time before — this is a frequent gas stop on my adventures — and the sun is much too low for a good panorama, inasmuch as it’s nearly the winter solstice. Really just warming up my camera. But the Sangre de Cristo Mountains are on the skyline, with Black Mesa on the right in the middle distance and the Barranco badlands in between.

The Sangre de Cristo Mountains form the east flanking uplift of the Rio Grande Rift, which I am more or less standing in the center of. For new readers (Welcome!): The Rio Grande Rift is a great crack in the Earth’s crust, extending from central Colorado to the El Paso area in west Texas, and more or less coinciding with the valley of the Rio Grande. It’s where the Colorado Plateau has pulled slightly away from the interior of the North American continent. The center of the rift dropped down while the ground to east and west popped up, and the resulting rift valley was filled with sediments about as fast as it formed. These sediments consolidated into the rock of the Santa Fe Group. (A group is a set of geologic formations that are related in some way.) The chief formation here is the Tesuque Formation, which is what we’re looking at in these badlands. When the Rio Grande finally plowed a route all the way to the Gulf of Mexico — a process taking some millions of years — the Santa Fe Group began eroding back out, producing the badlands you see here.

I guess I just never get tired of this area.

This is looking west. The upper gray beds are Puye Formation, which is relatively young (geologically) at less than 5 million years old. It’s debris eroded off the Jemez Mountains to the west. The pink, beds beneath are Chamita Formation, which is (obviously) more than five million years old, but mostly less than ten million years old. It’s the youngest Santa Fe Group formation in this immediate area, though there are much younger Santa Fe beds elsewhere. In fact, some geologists are inclined to include the Puye Formation in the Santa Fe Group, though I’d opine that it’s more closely associated with the Jemez Mountains than the Rio Grande Rift.

We arrive at Ghost Ranch.

The lowermost red beds are Chinle Group, likely Rock Point Formation. This is where most of the fossils in the area are found. Above are pink to tan sandstone cliffs of the Entrada Formation and a gray cap of Todilto Formation. The Chinle Formation is late Triassic in age, around 206 million years. The others are Jurassic in age, around 165 million years old.

It turns out we were having a little trouble connecting; the same storm that brought us that skiff of snow knocked out their power for two days. We finally get ahold of Gretchen, who needs another hour to open the museum. We take the time to hike the area.

(Click for a full-resolution image, as you can do with most images at this site.)

Gary notices something to the west.

Notice the terraced appearance of the otherwise very flat ground of the Chama Basin. Two possibilities occur to me: These may be a series of parallel faults, or they may in fact be river terraces from a river that no longer exists here. The climate has gotten a lot drier since the last ice age. Gary thinks they must be river terraces, and he’s probably right. The geologic map shows no parallel faults oriented this way in this area.

A magnificent view.

The vantage point gives a nice view of the stratigraphy here.

The red siltstone beds of the Chinle at the very bottom of the cliff form a very sharp contact with the overlying sandstone beds of the Entrada Formation. This sharp contact is found throughout the area and marks a period of some tens of millions of years that are missing from the geologic record — a discontinuity. Most likely the area was beveled flat by erosion after deposition of the Chinle and before deposition of the Entrada, an event called the J-2 discontinuity that is seen throughout western North America.

At the top of the cliff are thin limestone beds of the Todilto Formation. These were likely deposited in a sabhka, a kind of salt marsh on the margin of an ocean in an arid climate. The Todilto also commonly has an upper set of gypsum beds, mined in some places. It looks like these may be present here.

We return to the museum, meet Gretchen, and begin learning how to assist with her January class. Cleaning implements:

Yeah, the same kind the hygienist uses to clean your teeth. Some of these were in fact donated to the museum by a dentist.

Fossils already prepped; they give us something to aspire to.

Most are pliosaur scutes — bony plates armoring the skin of a water-dwelling form of early reptile. Gary and I will be entrusted with some unprepped pliosaur fossils to take home and practice prepping on. This is done under a big magnifier, using dental picks, toothpicks, cotton swabs, and water or acetone as solvent. The idea is to remove as much non-fossil from the fossil as possible without wrecking the fossil.

More bones, mostly tail vertebrae but also some ribs and other bones.

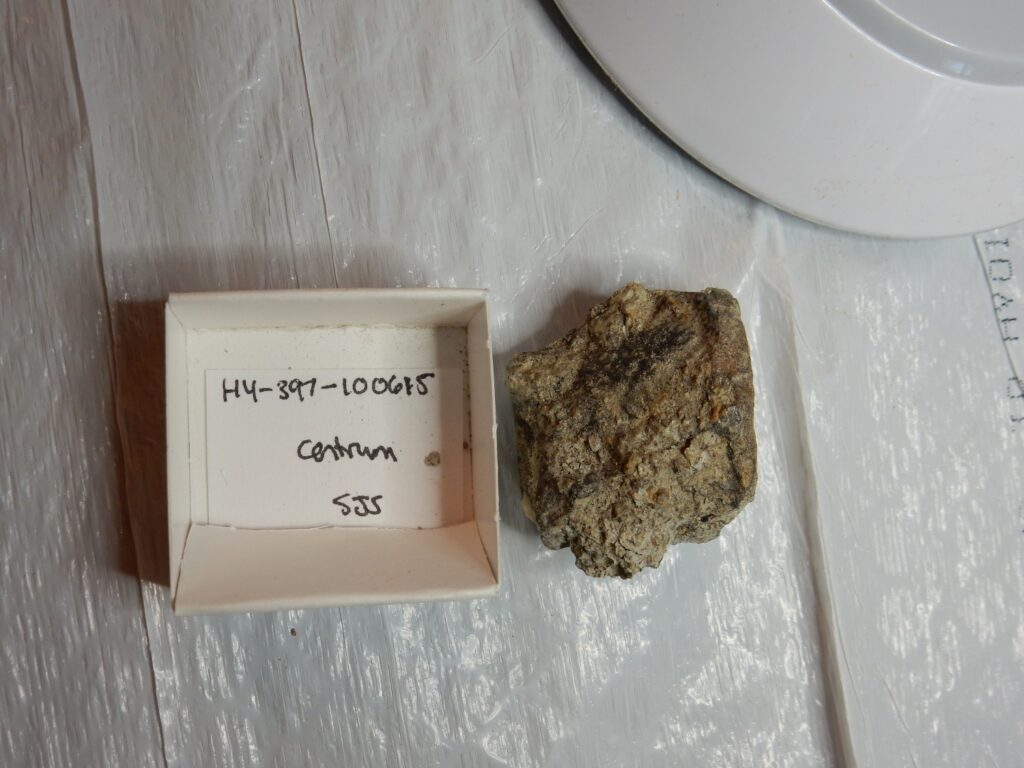

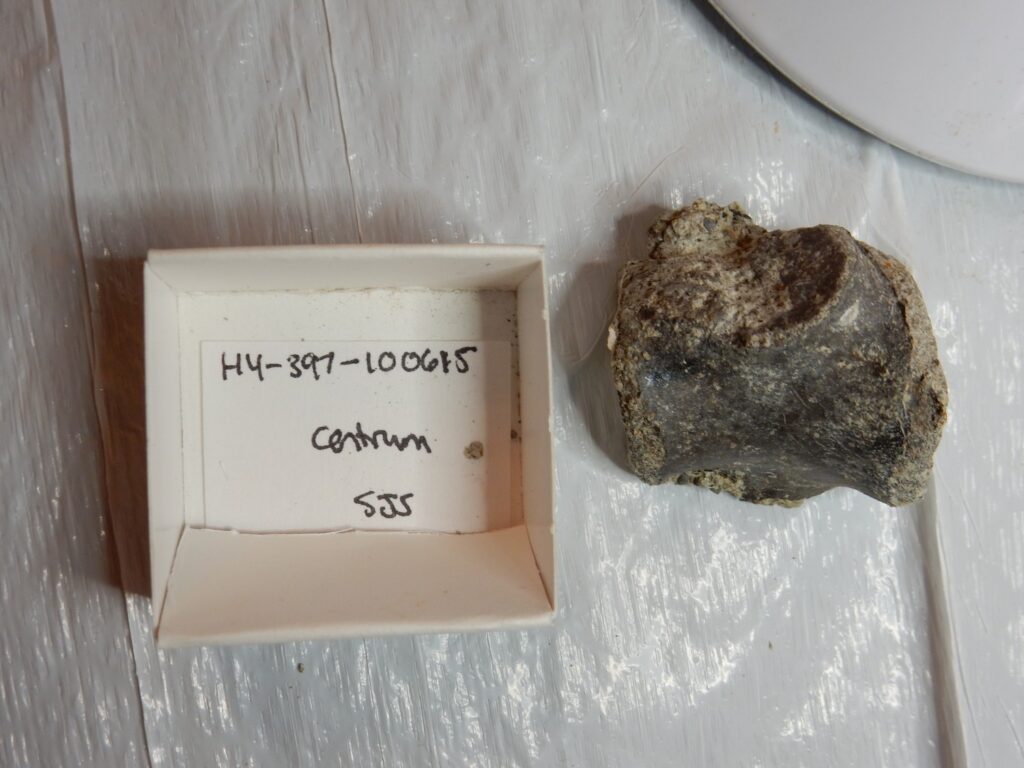

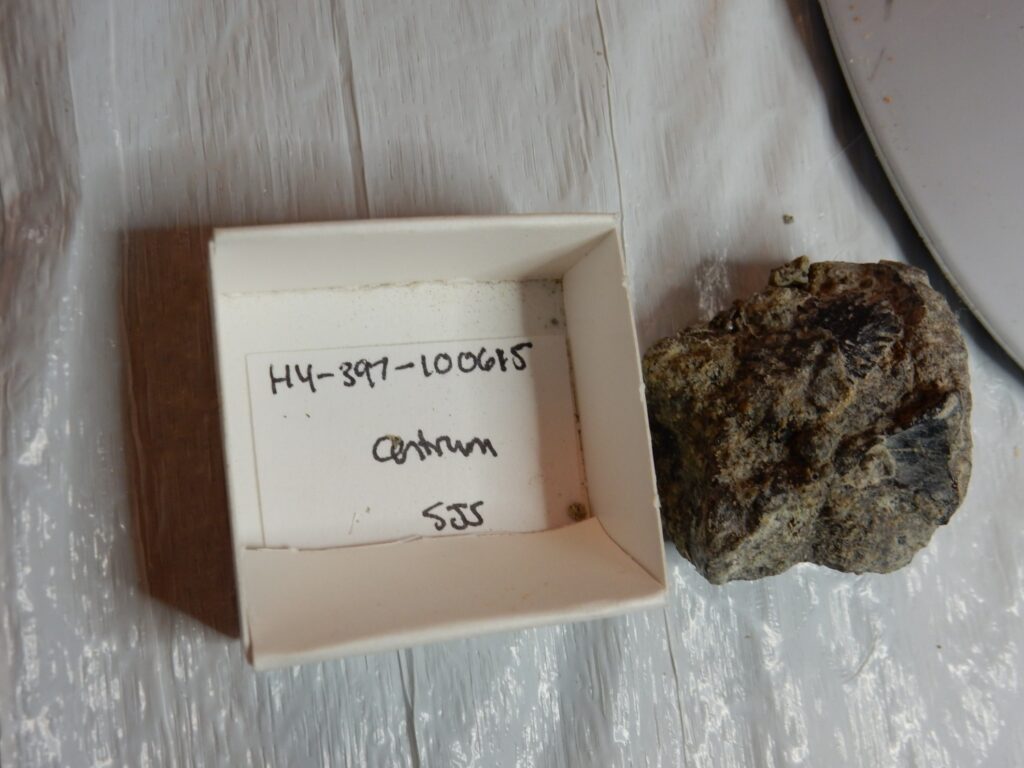

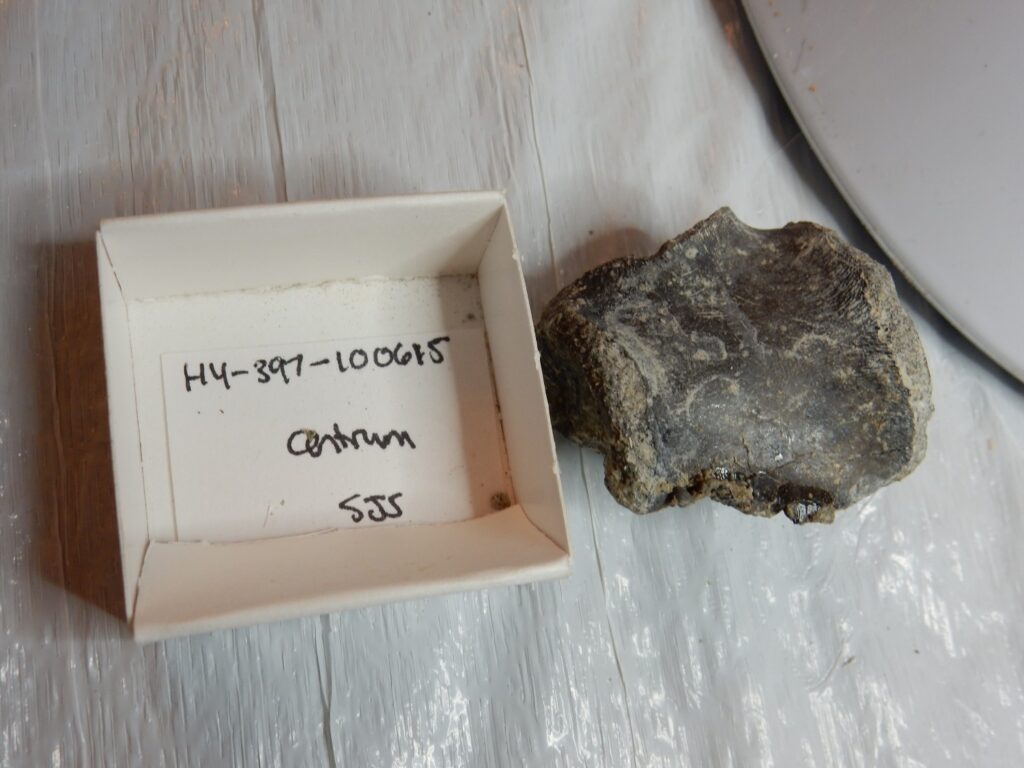

Stuff for us to practice prepping.

Obviously, as fossil bones go, these are not terribly important — that’s why we’re being allowed to practice on them. Still, it is way cool that we get to do this.

Back home the next day, I discover that Fox in enjoying my back yard.

My guess is a gray fox, Urocyon cinereoargenteus. They’re quite common in the New World. Wikipedia informs us that they actually like human-inhabited areas, which are avoided by their main predators. They are also apparently comfortable climbing trees, which may explain why this one is so fond of our wooden back porch.

Later in the afternoon, Gary and I try our hands at vertebrate fossil prepping. My piece before prep:

You can see that there is still a lot of gunk (“matrix”) encrusting the fossil. I will end up doing a lot of swapping with a wet Q-tip and poking with a toothpick or dental pick to dislodge matrix.

Gary is already at it.

Fossil surface with most of the gunk scraped off.

One side is in poor enough shape that it’s hard to tell where matrix ends and fossil begins.

However, you can see two surfaces that are now cleaned. The part at extreme left is a very thin crest of bone (a neural ridge?) and a small piece breaks off; I glue this back in pace with a special glue made of plastic dissolved in acetone. It’s strong but can easily be removed with more acetone.

Final results, at least for this session:

There’s been definite progress, but probably more could be done.

Christmas morning arrives, and Fox is back.

I’m not sure why I find it so touching that Fox feels comfortable this close to us.

Christmas presents.

I actually rarely use the fireplace; it’s mostly a backup if our local power or gas should fail. But I do like a fire on Christmas morning.

Fox continues his nap.

Time to unwrap presents. Mouser the Cat provides the laser light display.

Fox pretty much spends the day napping on our porch.

He stirs at evening; alas, the light is bad for my camera.

He was out there again this morning. In fact, he may still be out there now.

A Merry Christmas to you all.

Trying to pay attention to the science, but those fox pictures are so distracting! Very neat that it is comfortable in that environment.

I was looking through old pictures yesterday — cleaning out and reorganizing the photo album — and I found a picture of Fox from about this time a year ago. It’s his second winter with us.

I don’t know why I find that so flattering.