90th Birthday Wanderlust, Day 10: Y Mountain

I will be spending the rest of the week with Mom, at least when I’m not out exploring local geology. It will be an opportunity to visit and to record some more of her stories for Kira to transcribe.

This morning, after breakfast, I decide I’ll have a go at the Y Trail in Provo. This is a winding set of switchbacks up the steep western face of Y Mountain, part of the Wasatch Front, that is short but challenging. The trail (and mountain) get their name from a very large whitewashed “Y” placed there by the students of Brigham Young University, my alma mater. The guide book says the trail continues to the top of Y Mountain and that this part is much gentler. We’ll see what I feel up to.

As I arrive at the trailhead, I encounter the greatest threat to life and limb facing a geologic tourist in Utah: Utah drivers.

My experience with the people of Utah is that they are wonderful people. They are considerate of neighbors, generous, active in their churches and community, and look out for each other and for visitors, and I share a common faith with many of them. This makes it all the more surprising that, when some Utahans get behind a steering column, they turn into wild men. Perhaps it’s just that I spend more time in central Utah than any other conurbation except Albuquerque, so I just notice it there more. And it’s a conurbation with an unusual large number of young drivers, so perhaps it’s just demographics. Utah driver idiocy is mostly of the reckless young driver variety, rather than the senile old driver variety of, say, Arizona. And it’s fair to point out that it may well be that 95% of Utah drivers are excellent drivers, and it’s just the 5% who are lunatics who stand out.

But too many Utah drivers seem to think getting from point A to point B in an automobile is some kind of mortal contest.

So what prompts this screed? I’m looking for a parking place, and the parking area is on the left side of the road. I hit my turn signal and slow down, assuming that the driver behind me (who has been riding my tail) will understand I am about to turn left to park and will be patient. Instead, he hits his accelerator and roars around me to the left, such that if I had already started turning into my slot, I’d have been hit square in the driver’s side door. Idiot.

There are other incidents like this on this trip. I won’t belabor the point. Except: If you are a Utah driver and don’t understand why I’m upset at this driver, you’re part of the problem.

</rant>

We’re mostly looking at lacustrine deposits of Lake Bonneville here.

I saddle up and start out. The trail soon forks.

To the left is an interesting outcropping.

The map is a bit imprecise, and we are in the great Wasatch thrust fault zone here, so the geology is confused. But the tan rock forming most of the rock face is clearly Tintic Quartzite, a lower to middle Cambrian formation, in the ballpark of 530 million years old. Quartzite is sand that has been very thoroughly cemented, forming a very hard rock that is either regarded as very hard sandstone or as a metamorphic rock. The dark brown beds appear to be Mineral Fork Tillite, which is glacial debris deposited by the great ice age of 650 to 700 million years ago. This is the ice age hypothesized to have resulted in a “Snowball Earth” in which the entire planet, except for a small band of ocean along the equator, was covered with ice.

Mineral Fork tillite.

Notice the bluish patches. These may be sodium-rich minerals reflecting its deposition at the ocean bottom.

Tintic Quartzite:

I return to the fork and take the main Y trail.

It’s a very popular trail, though since BYU is presently on break, the numbers are not huge. There are joggers and casual walkers; I’m the only one I see with a backpack.

First switchback.

Each switchback will have a sign discussing some aspect of the area. Mule deer are common back home as well.

Second switchback. Gamble oak, ditto.

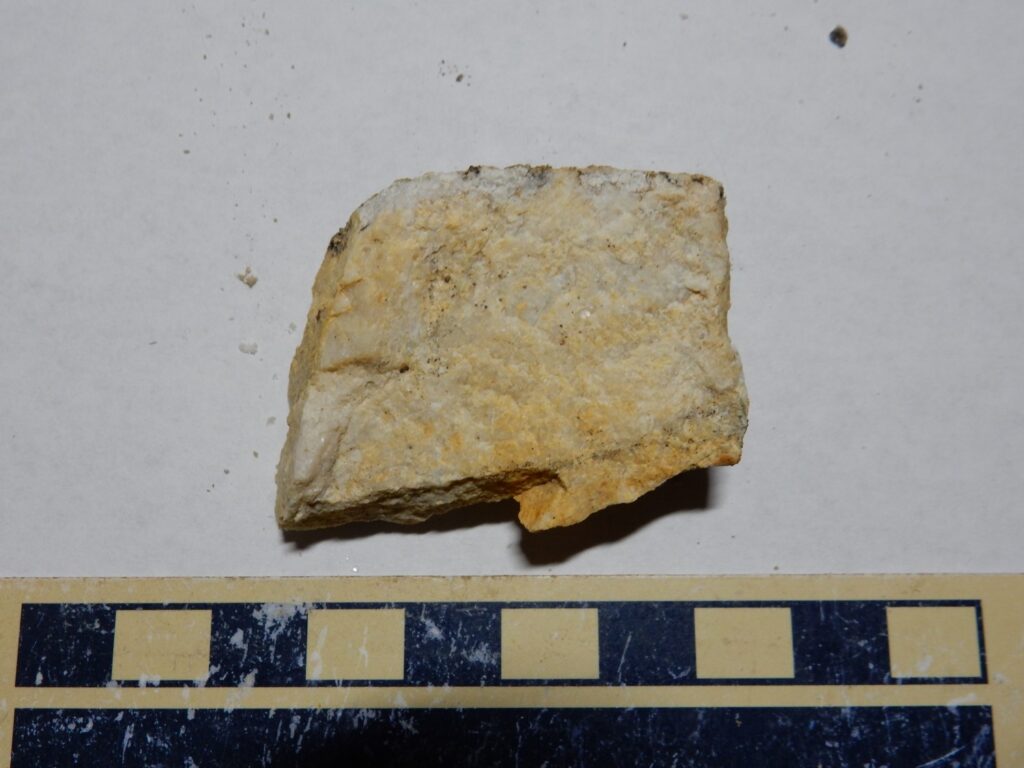

Rock by the trail. Since this is an area of colluvium (material that rolled down the mountain) this could have come from anywhere between here and the top of the mountain.

This, on the other hand, appears to be in outcrop.

This is thinly-bedded shaly limestone of the Middle Cambrian Ophir Formation.

Third switchback.

The Y on the mountain has been there since 1906 and is football-field-sized. It’s a prominent landmark throughout Utah Valley.

I miss one.

Sixth switchback.

The Y has now been thoroughly institutionalized. Some things really shouldn’t be.

This area is mapped as landslide, so the parent formation is not obvious.

Seventh switchback.

The Uinta ground squirrel seems to have tiny ears. I’m guessing this is a cold-climate species, unlike our warm-clime big-eared local squirrels.

Eighth switchback.

Sagebrush is rather familiar to us in Los Alamos.

Nowadays the lighting is permanently installed.

Another massive landslide boulder, provenance unknown.

We’re now at the bottom of the Y.

I’m puffing a bit, but persevere.

Middle of the Y.

Final switchback.

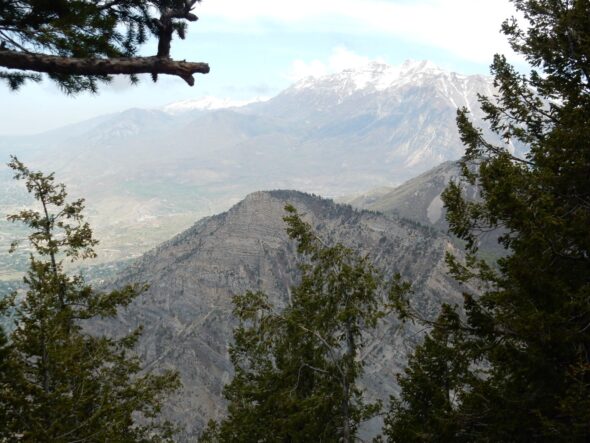

The view is nice.

The campus of BYU is directly below. Beyond is Utah Lake, and on the other side, West Mountain at left and the Lake Mountains to the right. At far right is the Bingham Canyon mine.

The mine is one of the largest open-pit copper mines in the world, and has produced 19 million tons of copper. That would fill a solid cube roughly 128 meters on a side. The ore is porphyry sulfide ore, in which fluids from an underground magma body rise towards the surface and deposit their load of dissolved metal sulfides.

I start down the trail to Slide Canyon. This climbs above the landslide zone and I start to see true outcrops.

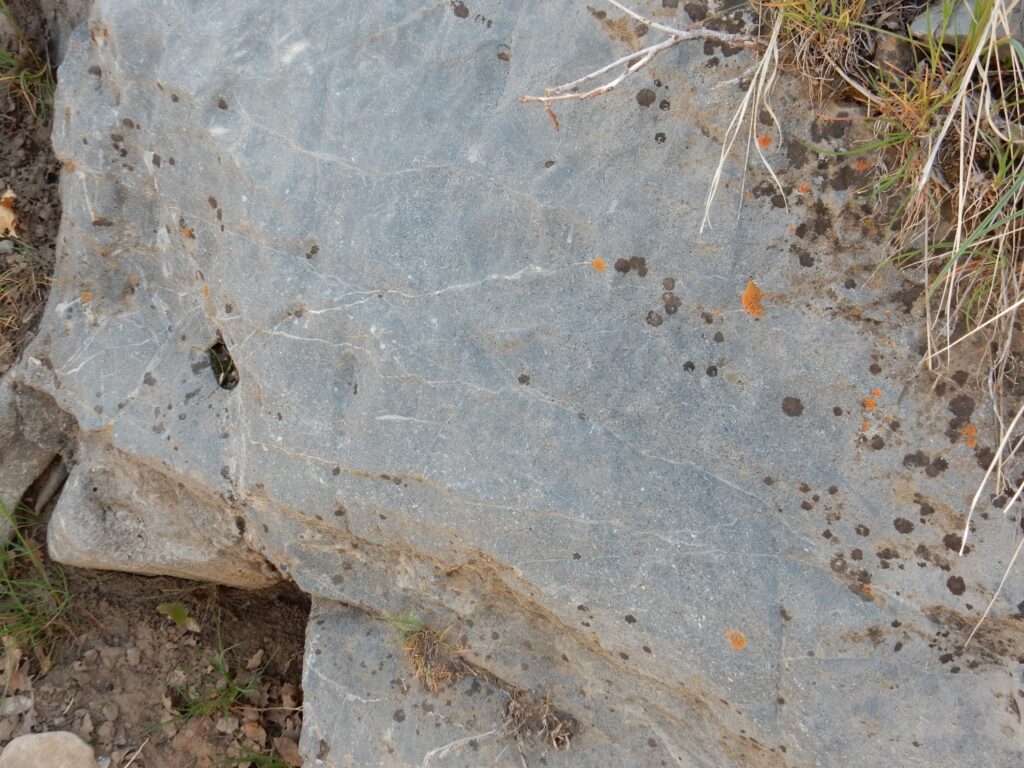

This is Middle Cambrian Maxfield Limestone, a thinly bedded gray limestone according to the map description. Seems about right. The map description does not describe it as fossiliferous.

Outcroppings to the south.

These are outcrops of the Mississippian Gardison and Fitchville Formations, with at least two faults running through the outcrops. My map does not describe these formations.

Another outcrop.

Ditto. The “eyes” in the limestone match the description of the Fitchville. The Cambrian through Pennsylvanian limestones making up Y Mountain were deposted when the Pacific Coast of North America was a passive continental margin, following the rifting away of Australia and Antarctica around the beginning of the Cambrian. Passive margins tend to slowly subside, and this allowed enormous quantities of limestone to be deposited in a shallow marine environment. How enormous? Wasatch Range enormous.

Some nicely bedded limestone. My GPS positions are going to be inaccurate in this mountainous terrain, but this is likely still Gardison or Fitchville Formation.

The lighter beds are layers of chert, a very fine-grained form of silica. These likely were deposited as radiolarian skeletons. Radiolarians first appear in the fossil record in the Mississippian, and were single-celled plankton distantly related to amoebas that secreted silica shells.

Another view.

Although my geologic map does not describe these formations, I can look them up on Geolex, The upper Gardiner Limestone is described as a massive cliff-forming limestone having pods of white chert. This seems to match.

The trail continues up Slide Canyon. Limestone with small fossils:

You’ll have to click for the high resolution image to have much hope of making these out. Crinoid stems, mostly. This is likely the Deseret Limestone, which is reported as containing abundant crinoid and coral fossils.

Fork in the trail. I go left, which seems more like to take me to the top of Y Mountain. The trail becomes quite steep; probably the most challenging section.

Looking southeast, where clouds are gathering.

Corral Mountain, I think. The mountain is covered with what look like logging roads, but may be avalanche suppression. The mountain itself is underlain by Pennsyvlanian Oquirrh Formation, here composed mostly of interbedded sandstone and limestone. The Oquirrh Formation is one of the most prominent formations in central and northern Utah. We’ll see plenty of it later.

Massive limestone, almost devoid of fossils.

This is almost certainly Mississippian Humbug Formation, which is mapped through this entire little valley and surrounding ridges. The formation is varied, with limestone and sandstone beds.

Humbug beds to the west.

The final trail to the top. I am concerned how fast clouds are moving in. But Squaw Peak to the north is very striking.

The uniform beds at top are also Humbug Formation. The more massive beds below are Deseret Limestone.

Humbug Formation along the trail.

I reach the top, and the clouds have already arrived. I am very disinclined to linger, but shoot a quick (and, unfortunately, badly focused) panorama.

Then I hurry back down.

Wildflowers.

Arnica, perhaps.

Too blurry for id.

Some kind of legume.

Hoodoo of sorts.

This is mapped as Gardison or Fitchville Formation.

It seems to fit the description of the lower Gardison Formation.

I come down to the level of the Y again, and stop for lunch and rehydration at the middle of the Y. To the north are beds of the Tintic Quartzite.

I reach my car and head to the Bean Life Sciences Museum at BYU. BYU is taking masking a little too seriously for my tastes.

I am required to wear a mask, even though I am fully vaccinated. The museum kindly provides me one.

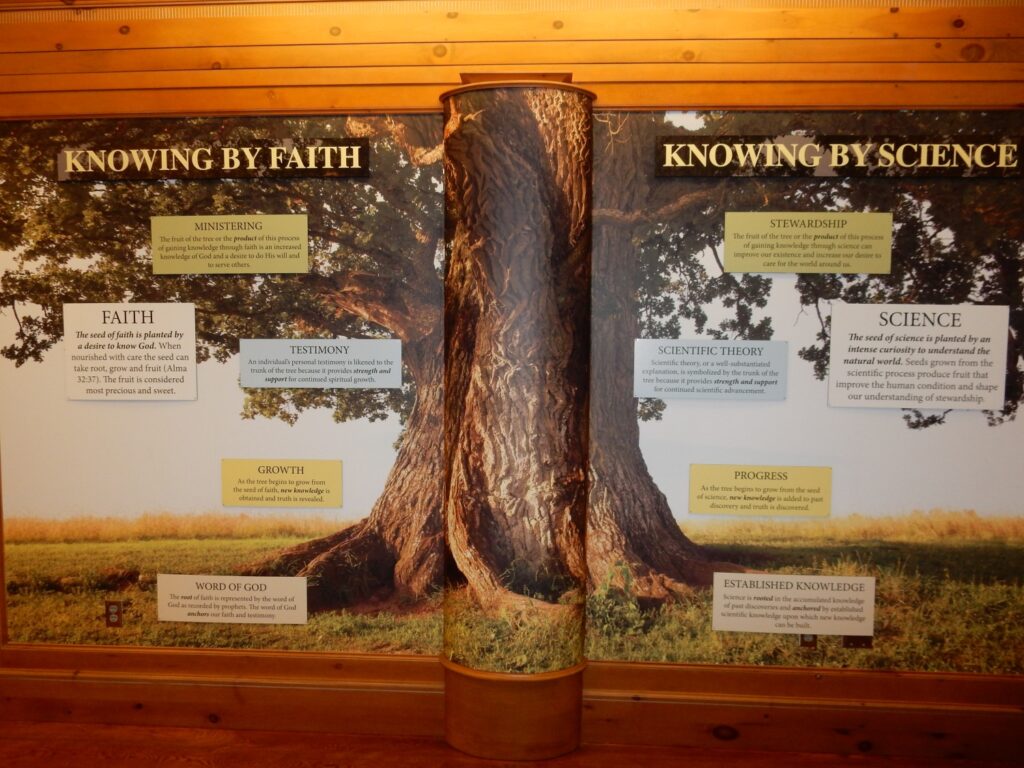

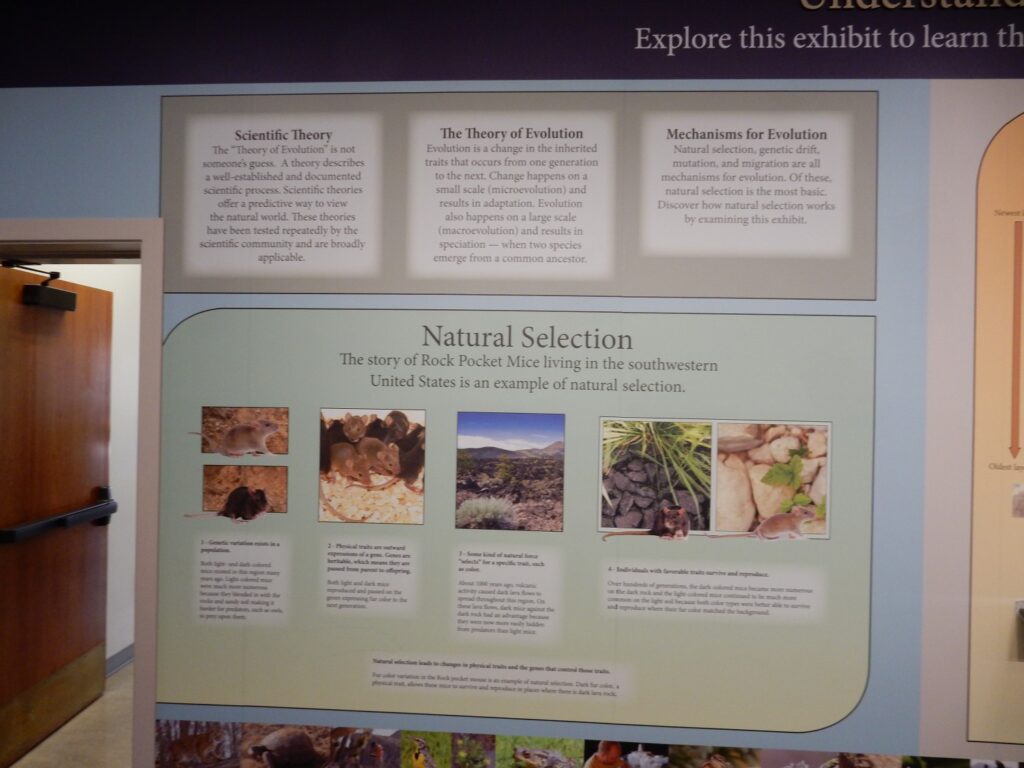

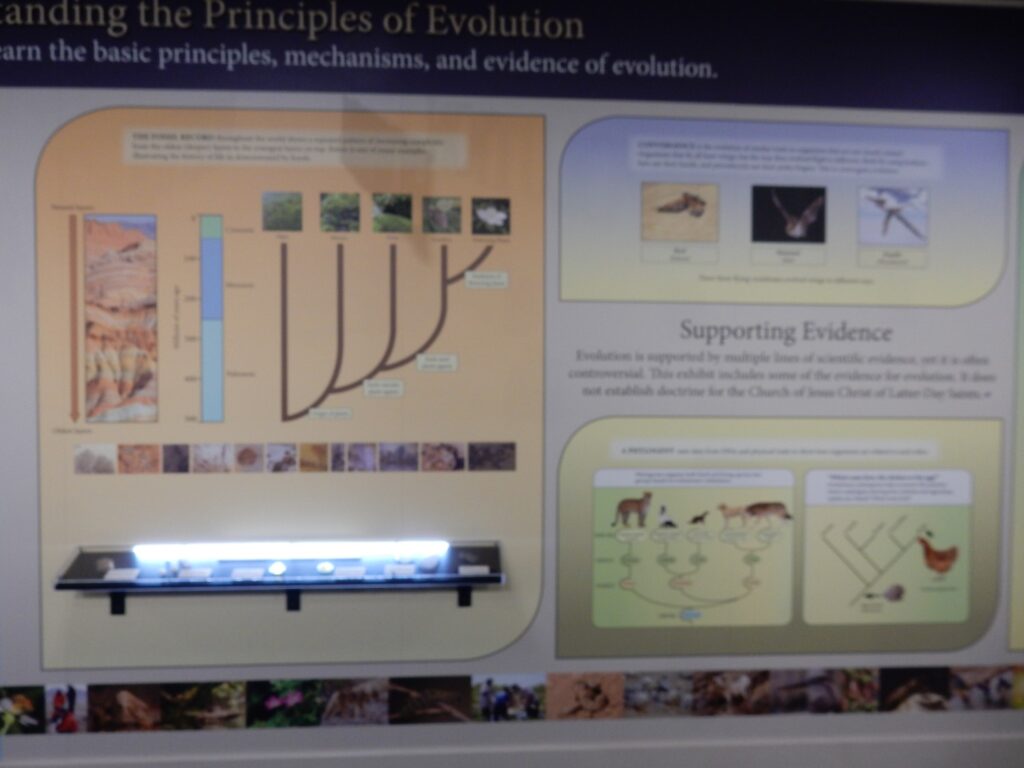

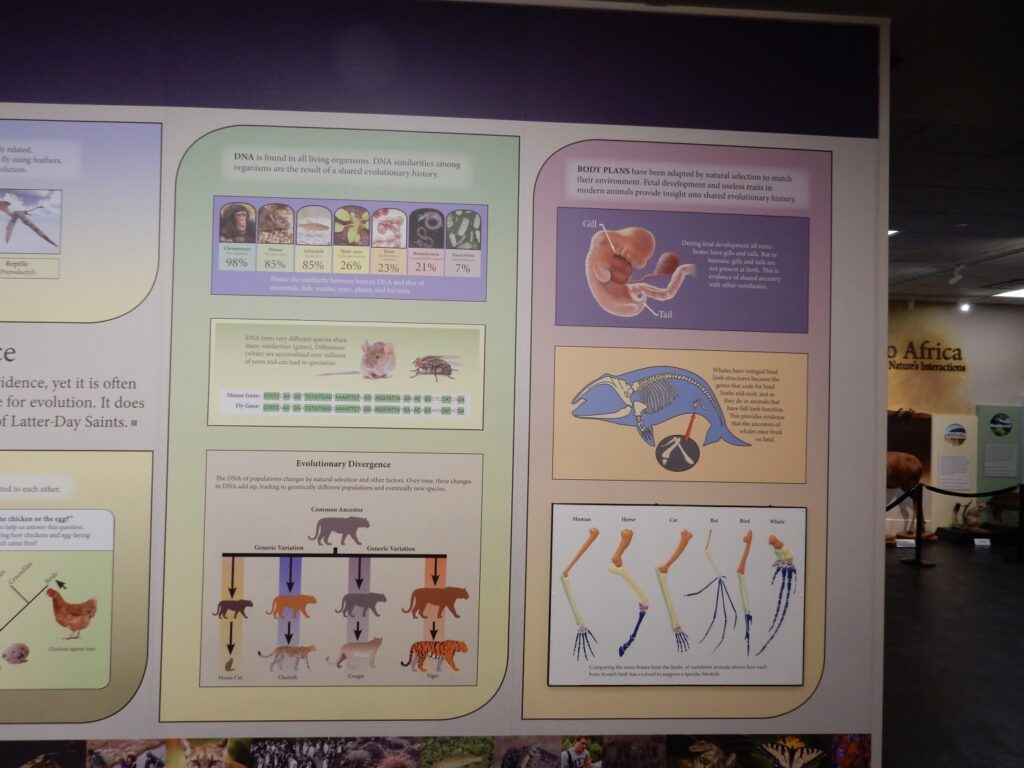

BYU is a conservative church university with a very modern geology department. This makes for some interesting displays.

With which I am pretty much on board.

There is a striking display of Morpho butterflies.

The museum is fun, but I was half expecting a paleontology section and there is none. I ask at the desk; yes, BYU has a separate paleontology museum. It’s small but fun.

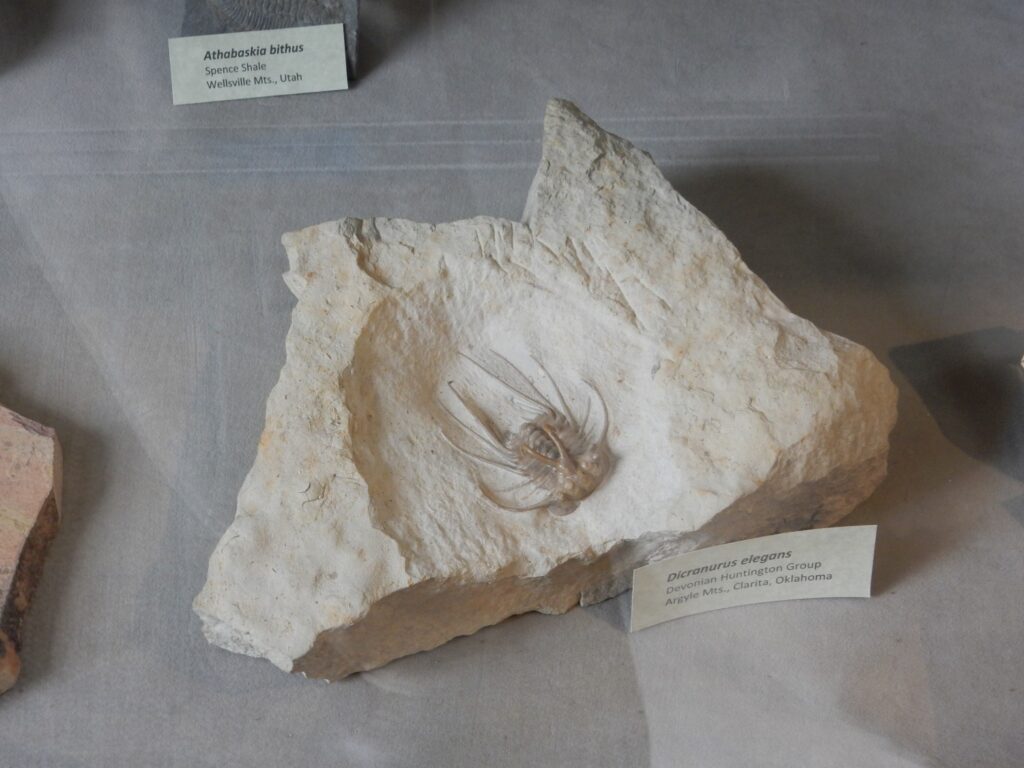

Fully dressed up trilobite.

Excavating this from its host rock was done skillfully.

Fossil mollusk covered with fossil barnacles.

Sauropod hip.

Complete skeleton.

The raised head is very typical of such skeletons. It’s a result of the dead tendons shrinking in a characteristic way.

Stunningly well-preserved petrified wood.

Cephalopods.

Relatives of squid and nautilus. Particularly characteristic of the Cretaceous.

I return to Mom’s for the remainder of the day. My trail guide gives the mileage to the top of the Y as a little over two miles (round trip) but did not give mileage for the top of the mountain. I Google it up and discover I’ve hiked eight fairly strenuous miles. Nice to know I still have it in me.