Wanderlusting the Cerros del Rio

My wanderlusting began some years ago, when I decided to celebrate my (mumble mumble)th birthday by going somewhere I’d been living close to most of my life, but never actually visited, as a kind of birthday adventure. That first wanderlust was to the Buckman area on the east side of the Rio Grande. It was not particularly ambitious, and most of the pictures didn’t turn out, but it was a nice start.

It’s been a tradition ever since.

Yesterday was my birthday again; to be precise, my 26th annual 29th birthday. I decided to celebrate by driving out to an area I’ve lived close to most of my life, have photographed numerous times from a distance, but have never actually set foot on: the Cerros del Rio, the high basalt plateau just across White Rock Canyon from Los Alamos (map).

Unless it’s the Caja del Rio. Both names are in common use for this area. I’ve done a bit of Googling but cannot find much on how two separate names arose, except that part of the plateau is on the Caja del Rio Grant. Geologists seem to prefer Cerros del Rio.

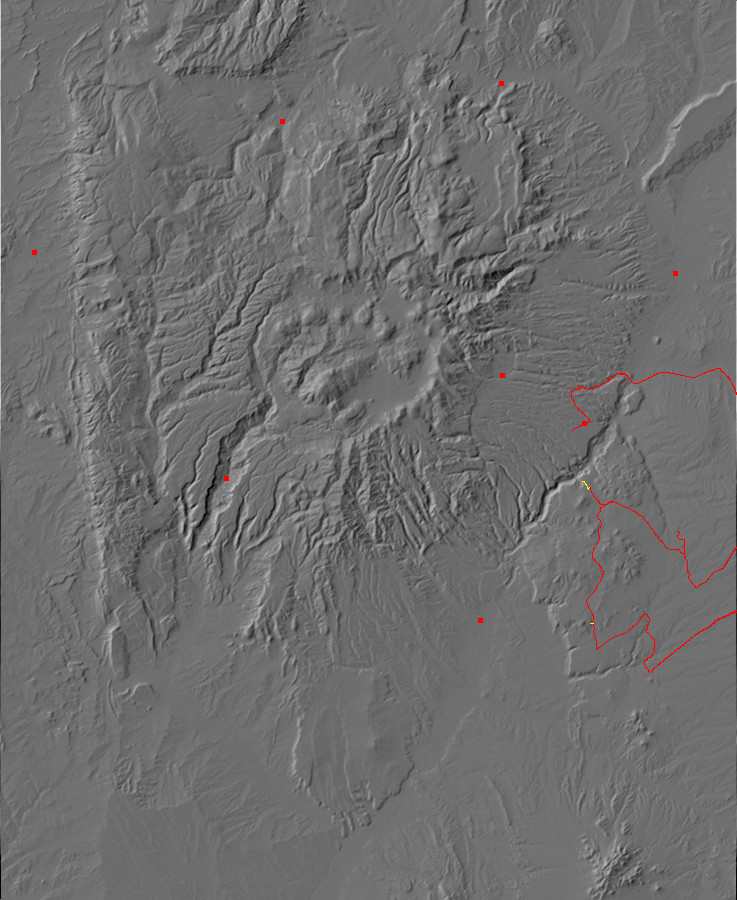

The plateau is surrounded by escarpments, leaving just two access points by vehicle. These are connected by Forest Road 24 (most of the plateau is Santa Fe National Forest land) and my plan was to make a loop from one access point to the other, with a diversion to the east rim of White Rock Canyon. The road did not look passable all the way to the rim, so my plan was to hike the remaining distance once I’d gotten as far as I could get.

So yesterday I ate a good breakfast, loaded up my gear and a sack lunch, and headed out to Santa Fe in the Santa Fe. Clownie the Wonder Car is retired now, a story I told in my last post, and I would be taking Cindy’s old Hyundai Santa Fe. It has something like 120,000 miles on it, but it’s in much better shape than Clownie, and it has considerably better ground clearance. Cindy would have to start breaking in the new car, which she has been hesitant to do; there’s something very traumatic about that first door ding, and since she works on a small college branch campus, that door ding is certain to come sooner rather than later. (College kids being what they are.)

My route took me past Santa Fe to La Cienega (map) where the fun began. La Cienega is located on marshy ground along Cienega Creek, and it is a very old settlement, supposedly once the bread basket of Santa Fe. My impression is that the area has suffered partial gentification in the last few years. The creek has cut deeply enough to expose some interesting geology in the area, and I’ve visited here a couple times before. Still, there’s always something new.

The first thing that caught my eye was a fairly dramatic contact between the Galisteo Formation and the Ancha Formation (map).

The Galisteo Formation is the red beds at the bottom. This is a relatively old rift fill formation, perhaps the oldest in this part of the Rio Grande Rift, though its age is quite uncertain; it contains almost no fossils. The best estimate is around 30 million years old.

The light tan beds on top are Ancha Formation. This is the youngest rift fill formation in the area south of Santa Fe, perhaps younger than 2 million years in some places. The Ancha Formation thins out and disappears to the north, and becomes fairly substantial further south.

Further up the road (map), Ortiz Monzonite is exposed. This has been dated to around 20 million years in age.

Monzonite is an intrusive rock (a volcanic rock that cooled slowly underground) that has an intermediate silica content and a moderately high alkali metal content. This is a common rock along continental rifts such as the Rio Grande Rift. Here’s a sample.

Under the geologist’s loupe, one sees smaller gray crystals, probably alkali feldspar, with larger white crystals, probably plagioclase, and lots of oxidized iron that was probably once hornblende or another iron-rich mineral. The presence of both alkali and plagioclase feldspar is characteristic of monzonite, and the absence of visible quartz keeps this from being a quartz monzonite. (Tangent: Many of the prominent buildings of Salt Lake City are build with “granite” from a nearby quarry that is actually quartz monzonite.)

Further up the road (map) is a hornblende trachyandesite dike that I photographed during an earlier wanderlust. I paused here to take a closer look, hoping to spot some xenoliths (bits of country rock caught up in the magma that didn’t quite melt.) I was not disappointed.

Xenoliths get geologists’ attention because they sample the rocks deep below the surface, including the lower crust and upper mantle. And this dike has apparently gotten a lot of geologists’ attention, because there are drill holes all over it where geologists have taken samples. I’m guessing most of these are of xenocrysts rather than the trachyandesite itself, which, while pretty and interesting, is not worth that much attention.

I noticed some contact metamorphism around the dike, and what looked like bits of shale.

I scrambled up the very loose shale-covered slope (yeah, not a great idea with my shoulder) to get a closer look.

You know, this looks for all the world like Mancos Shale. And it’s not impossible: There is quite a lot of Mancos Shale exposed in the Cerillos Hills just south of here, where it is intruded by Ortiz monzonite. The question is why it would be preserved in this area just around this dike. Perhaps the shale was metamorphosed by contact with the dike just enough to make it more resistant to weathering.

From here it was north along Highway 54B and Highway 56 to La Cieneguilla (map).

Click to enlarge and read the sign.

I wasn’t actually planning on it, but when I passed a parking area with a big sign saying “Petroglyphs” (map) I decided it was time for a short hike to the Cerros del Rio escarpment to look at the petroglyphs. Anyway, it was time to check my blood sugar and eat my morning orange, and my bladder was wanting some attention.

Here’s the east escarpment of the Cerros del Rio (map).

The escarpment almost disappears further to the north, where the two highway access points are, then becomes substantial again. This portion forms the northeastern boundary of Tsinat Mesa, which is the very flat southern portion of the Cerros del Rio (map). The rock here is a trachybasalt dated at 2.68 million years old. My geologic map is not so specific, but this is probably the sodium-rich trachybasalt known as hawaiite.

The sediments beneath the lava cap are rich in red granite fragments, and are shown on my map as Ancha Formation. The granite came from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to the east and was probably transported to this area by the ancestral Santa Fe River.

Here’s the escarpment a bit further south (map).

Just south of here (map), the trail climbs the mesa (becoming rather indistinct in the process) and the petroglyphs are numerous.

I know little about petroglyph iconography. But then, so do archaeologists, who have a number of different notions about their significance. I have seen petroglyphs throughout the Jemez area, including petroglyphs carved on Bandelier Tuff and in Mesozoic sedimentary rock. Basalt seems favored but not decisively so. Some petroglyphs are found close to ancient settlements, but I’ve also seen petroglyphs in areas far from any known settlement, including White Rock Canyon (map) and the Hagan basin (map)

Here’s one where I can at least name some of the iconography.

The figures appear to be Kokopelli, a fertility deity shared across several native American cultures. Kokopelli has been thoroughly commercialized in modern New Mexico, which I find vaguely regrettable.

There was a good place nearby to hike to the top of the mesa, find a bush, and take care of my bladder. Then back to the parking area, north to Route 56C (map), and up onto the Cerros del Rio.

The road passed a cinder cone that had been cut in half (map).

The dip on the beds strongly suggests that what looks like a breach in the cinder cone wall is, in fact, a breach in the cinder cone wall. The breach is now filled with sediments and blocks of the overlying lava. I was not up to scrambling up the hill, but satellite image shows nothing up there anyway — this cinder cone must have been buried under a thin layer of basalt forming the top of the mesa.

And, yes, that’s the new Wandermobile. The ground clearance is generous, although the car does not have four-wheel drive. It should serve me well. (Evil Kent: “Meaning, you’ll run it into a ditch even further out in the middle of nowhere than you could have with Clownie.”)

Here’s the beds close up.

Those are my car keys at lower left for scale. These are very typical cinder beds, thrown up around a vent where blobs of basaltic lava were blasted into the air as gas escaped from the lava, with the blobs cooling in the air before landing around the vent. Such vents often also have a flow of degassed lava emerging from the base of the cinder cone, but here the flow likely would have been to the northwest, and is now buried under later flows.

The cinder has some commercial value. It is possible, and my geologic map seems to confirm, that the breach here was actually excavated for cinder and is not a natural feature. Further up the road, there is an old cinder mine, now inactive, and another that is still active that I did not visit today (map).

The inactive mine has a locked gate, but I found a side road up a nearby hill (map) from which I could get a distant photograph (map).

The cinder is here oxidized to a deep red. This makes the cinder valuable as decorative stone, and it is also used on highways for traction. I wondered if it was also used in cinder block, but the cinder in cinder block is apparently clinker from burning coal or slag from the manufacture of pig iron and steel.

Getting the Wandermobile up this hill was its first real test. The road wasn’t awful, but it was a bit rocky and rugged. No sweat. In fact, whereas I could sometimes imagine Clownie saying “Nope, nope, nope, not going down that road”, the imaginary voice in my head for the Wandermobile was saying “No sweat, boss.” Well, what fun is that?

I got back onto the main road and headed southwest — for quite some distance. Tsinat Mesa is miles and miles of miles and miles (map).

Well, actually, it’s only about three miles to the opposite side of the mesa from here, but it seems longer when you’re driving it relatively slowly on a dirt road. As you can see, the road is quite excellent here, but it gets worse later. I could probably have taken Clownie down it, but I was glad to have the new car to put through its paces.

I paused southeast of Tetilla Peak for a panorama of the hills forming the northern boundary of Tsinat Mesa (map).

Tetilla Peak is the shapely mountain to the left, which is a distinctive landmark visible for great distances. At 7206′, it is not actually the highest point in the Cerro del Rio (that would be Colorado Mountain at 7300′) but it is the most prominent. It is also one of the older features of the Cerros del Rio, erupted 3.04 million years ago. What makes this more surprising is that it has a cap of dacite that is the most evolved lava in the entire Cerros del Rio. Evolved: Magma becomes more silicic the longer it sits in the crust, both because it absorbs relatively silica-rich crustal rock from its surroundings and because low-silica minerals crystallize out as it cools. But the age may be off; magnetic data and field relations suggest the age is more like 2.7 million years.

I got to the National Forest boundary and an abrupt turn north on Forest Road 24 (map). Here I found a recreational vehicle parked, with no one around. Not to worry; I got about half a mile up the road and saw a bearded nature lover jogging the other way, surrounded by a flock of terriers*. These proceeded to swarm around my car, yapping away, and forcing me to stop lest I run over one. (They’re a hassle to wash out of your tire treads.) Their master thanked me for my forbearance as he jogged past, and presently the dogs followed.

*I know. A group of dogs is usually called a pack or a kennel. But when they’re small terriers I insist the correct term is “flock”.

The road passes close to Tetilla Peak, where the ground becomes a bit rough and the Wondermobile got its first really good workout. The road was quite rocky and rutted at points; I’m pretty sure I would have turned around if I had been driving Clownie. I got looking at the mountain: Doesn’t look so bad. It would be cool to get a panorama from the top. So I stopped and started hiking west to see if this was feasible.

It’s always bigger than it looks (map).

This is just the face of the andesite flow at the foot of Tetilla Peak. Andesite magma is viscous enough that its flows can be quite steep like this. Not looking promising for a hike, if I’m going to have time to see anything else in the Cerros del Rio. It didn’t look better when I got right up to the face of the flow (map).

It is interesting,though, to compare the basalt to the left of the arroyo with the andesite to the right. The basalt is probably younger, but has been eroded away where it made contact with the andesite flow. I crossed the arroyo and climbed up far enough to grab a chunk of the andesite, but apparently I didn’t climb high enough, because what I grabbed doesn’t look like andesite.

Sure, the color is within the andesite range, and the presence of plagioclase and hornblende phenocrysts (white patches and dark needles) is typical of andesite, but the rock also has green patches of olivine. Olivine andesite is not unknown, but it’s decidedly uncommon and noteworthy, and the geologic map of the area mentions no olivine in the andesite of Tetilla Peak, only in the basalt around it.

I gave up on climbing Tetilla Peak. I will probably want to come back and try it another time, but with at least one companion, the whole day ahead of me, and with the route better planned. It turns out the best approach is probably from the north-northeast. Today, I’ll stick with a first reconnaissance of the Cerros del Rio.

Continuing north, I got to a spot (map) with a nice view of Colorado Peak, which is apparently the high point of the Cerros del Rio.

Colorado Peak is underlain by andesite about 2.6 million years old. The flat top is surrounded by a ring of dikes. These I’d like to check out sometime, but the hike would be a long and rugged one from the road.

“Say, do you know the way to San Jose?”

“Neigh.”

The horse had a somewhat wild look about it. I recall a “human interest” story about wild horses in the Cerros del Rio in the news, but that was years ago. I don’t know for sure whether this is a mustang determined to stand its ground, or a stock horse used to automobiles.

Further on was a good spot (map) for a view of Cerro Ruiz.

Cerro Ruiz is underlain by 2.61-million-year-old andesite. You may be seeing a pattern here: All the peaks are underlain by andesite. Why, yes, and this is why they are peaks. Basalt lava is relatively low in silica, relatively fluid, and flowed out freely to form the flat surface of the Cerros del Rio. Later, more silica-rich, and therefore more viscous, andesite lava was erupted to form the hills and peaks.

Next I came to a spot (map) with a really good view of the San Miguel Mountains to the west (map).

The picture doesn’t do this justice. The San Miguel Mountains are an early eruptive center of the Jemez Mountains; the high point, St. Peters Dome, is about 8.5 million years old, while some of the flows are as old as 12 million years.

Next is Cerro Rito (map) to the east.

This is underlain by basaltic andesite a bit younger than the other features we’ve seen so far, at 2.53 million years old.

Incidentally, the rock under most of these peaks takes the form of cinders, while the lower slopes are solid flows. This is quite typical of cinder cones.

This is also a good spot for viewing Cerro Micho.

This one is a little older, being underlain by andesite that is about 2.76 million years old.

Up over a rise (map), and we get our first view of White Rock, across White Rock Canyon.

I’m now just seven miles or so from my house, but a good hour and half away, because White Rock Canyon is in the way.

Another turn (map) and Montoso Peak comes into view. This is very prominent on the skyline directly south of my house.

Montoso Peak is underlain by basalt 2.59 million years old. The low-viscosity basalt has produced a mountain with relatively gentle slopes.

“Iota, kappa, lambda …”

“Moo.”

Montoso Peak again in the background.

Now the real adventure began. I found the turnoff for the canyon rim (map), with a truck and trailer nearby but no one visible. (The whole day, I saw just one other person — the dog owner — and heard occasional distant gunfire, but that was it.) The road became significantly worse; the Wandermobile began really showing its paces. I just about gave up at one spot (map) where there was a rather deep dip in the road, full of boulders and branches.

“You think you’re really up to this, Wandermobile?”

“Sure, why not?”

I hopped out, walked ahead, and decided maybe I could do it. And I could. Didn’t bottom out at all. I could not have done that in Clownie.

Finally, I hit a bit of road (map) so deeply gullied that I chickened out. Anyway, I was close enough to hike the rest of the way.

It was worth the hike to the rim (map). The view was magnificent. But, two frames into my panorama, my camera informed me its batteries were running dead and turned itself off.

Well, shucks and other comments. I had left the spare batteries in the car.

I managed to squeeze out a few more frames by letting the batteries rest between shots. Somehow it came out as a fairly decent panorama.

The deep valley in the first four frames is Montoso Maar. This is likely one of the oldest parts of the Cerros del Rio, formed when basalt magma rising to the surface penetrated sedimentary layers that were saturated with water. The resulting steam explosions laid down very thick beds of cinder and pulverized country rock, forming a kind of volcanic feature called a maar. This must have been subsequently buried by more sediments and by thick basalt flows from Montoso Peak. When the Rio Grande cut its canyon to the west, this exposed the maar, which has since mostly eroded out.

Montoso Peak itself is the peak on the skyline in the first frame, and its flows extend across the next two frames. In the last two frames, we see the far rim of White Rock Canyon, with Bandelier Tuff sitting on top of Cerros del Rio Basalt sitting on top of Santa Fe Group sediments. The mouths of several tributary canyons to White Rock Canyon are visible. In the next to last frame, the San Miguel Mountains are on the skyline, and the skyline in the final frame is the Sierra de los Valles west of Los Alamos. You can see one of the technical areas of Los Alamos National Laboratory on top of the mesa on the boundary of the two final frames, with a large VLA dish telescope. The tributary canyon to the right of the mesa is Ancho Canyon.

Note the junked appliance in the foreground in the final frame. Geologists sometimes refer to this as “locally-derived anthrogenic colluvium”, or, when it consists of automobile parts, simply as “Detroitus.”

Here’s a closer look at the maar beds.

Notice the great thickness of the beds — several hundred feet in this area. This must have been a truly enormous maar, though not as large as the enormous Seward Peninsula maars in Alaska, which are a thousand feet thick.

It was now a little after 3:00, and time to start heading home. (In my flight plan for Cindy, I promised to be back before sunset.) I retraced my steps, turned the Wandermobile around, and headed back, picking my way across the one really bad spot in the road a second time. I reminded myself that my worst mishaps in the past were always on the return leg, when I got a little too cocky, and I tried to stay vigilant. It seemed to work.

On my way back to the main Forest Road 24, I paused to photograph the Ortiz andesite flows to the east.

The whole area north of Ortiz Peak is a wild maze of steep-sided andesite flows, quite striking on the topographic map (map). The andesite here all erupted from around Ortiz Peak, and is one of the younger flows in the Cerros del Rio at 2.32 million years old. This seems to rule out the possibility that its rugged topography is the result of more extensive erosion that other parts of the Cerros del Rio. Looking at the topo map for the area, I get the sense that most of the andesite flows had a tendency towards this deeply lobed structure, but none were nearly as voluminous as the Ortiz flows and so did not fully develop this structure.

I got back to the main road and turned east to my exit point from the Cerros del Rio. I paused at a point south of Ortiz Mountain (map) to get a picture.

That’s where all that andesite came from.

A little further on (map) I got a nice photograph of the Twin Hills.

These are also relatively young, being underlain by basaltic andesite with an age of about 2.53 million years.

I descended off the mountain, passing an archery range marked with an enormous arrow (naturally) and reaching pavement at Caja del Rio Road (map). I headed north along this in hopes of seeing the contact between the Ancha Formation and the Tesuque Formation in one of the road cuts. To the west, I got an impressive view of Ortiz Mountain (map).

And I found my contact in a road cut (map).

The Tesuque Formation is the reddish beds at bottom, full of bits of red granitic rock. This has to be Lithosome A, though I can’t guess which member. The tan beds on top are Ancha Formation. I checked these coordinates against the geological map when I got home; yep, there’s a contact between the two right in this area. Neat.

Time to go home. I found my way to the Veterans Memorial Highway and from there to White Rock. Where I found waiting for me a sugar-free cherry pie, a new electric razor, and a new book, in celebration of my birthday. I needed the razor; the old one had batteries so worn down with age that the heads did a kind of lazy spin that was not terribly effective at removing my stubble. The new one gave me my first really clean shave in months. The book was a field guide to sedimentary geology. The cherry pie was delicious.

Not a bad birthday at all.

These keep getting better and better.

You’re very kind, Set.

Just discovered, from perusing the geological map, that the white area just above the maar deposits is a bed of El Cajete Pumice. That stuff got around.

About 40 years ago I ventured into Montoso Maar. It was a wild experience. There were several drop-offs you had to negotiate. The geology was extremely interesting.

Pingback: Wanderlusting Tetilla Peak | Wanderlusting the Jemez