Wanderlusting El Cajete

The weather has been heavy monsoon most of this week, which is good and bad. The good, which in the larger scheme of things is what really matters, is that the monsoon started rather late and we need it to be heavy. The bad is that it makes for lousy wanderlusting weather.

Nevertheless, I got up early Friday and checked the weather. It was clear everywhere but over the Jemez, which had a thick cap of clouds. Well, maybe I’ll drive up there anyway. If I hike quickly, I should be able to get to something interesting before the rains hit.

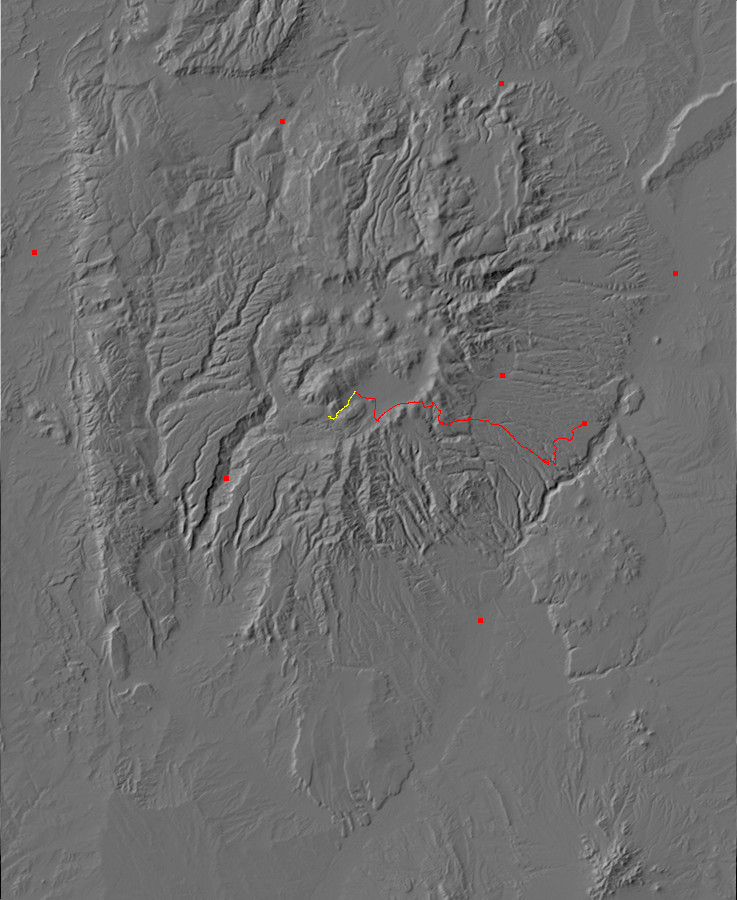

Given that it was an iffy day for exploring, I decided on one of two places whose trail heads could be reached by Park service van, so that I would not need a back country permit. The first was Cerro Pinon, which is a small hill where Valle Jaramillo joins the Valle Grande. It’s interesting because it has a nice sequence of early Valles beds: Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, at the base; then Deer Canyon Tuff; massive Deer Canyon rhyolite flows; and, finally, a mantle of debris flows. I don’t have any decent photographs of Deer Canyon for the book. The other choice would to to hike to El Cajete from the bunkhouse. Since El Cajete is the vent area for the most recent eruptions in the Jemez, it’s another one I want to photograph for the book.

Arriving at the Preserve visitors’ center around 9:00, and examining the map at the headquarters, I saw that there was a back country parking spot much closer to Cerro Pinon than I realized. This meant it would be an easy stop some other Friday when I had a back country permit. I decided it would be El Cajete, though I’d have to risk getting a good soak: It was heavily clouded over. A young ranger pulled a van around and I loaded aboard, after swapping my sneakers for hiking shoes and making sure I had everything I needed in my backpack. Wait: I had the folder and explanatory notes for the Valles geologic map, but not the map itself. Well, shucks.

I learned on my way out to the trailhead that the ranger driving the van was new to the area, having arrived just three months ago; that the vans were also very new, everyone was still getting used to them, but they were way cool (being practically noiseless); and that I had a good chance of getting soaked if I wasn’t done by a little after noon. She dropped me off at my trail head.

I slathered on bug spray and sunscreen, the latter perhaps a bit superfluous with the heavy cloud cover, and proceeded down the trail.

Beware of hiker:

Part of the first stretch of trail took significant damage from the Las Conchas fire in 2011.

You will also note that the trail, an old ranch road, is rather muddy from recent rains. This wasn’t the worst spot, but most was much better.

For example:

I think there was a spot even worse than this, but I didn’t think to photograph it. Fortunately, most of the trail was much drier.

This puzzled me.

This was posted along a stretch of road with no nearby buildings and no nearby crossroads. Look, I’ve gotten pretty lost driving on forest roads, but I’ve never gotten this lost hiking.

Emerging from the forest near here, I was taken with the view of South Mountain.

You can see that it’s a cloudy day. Cerro del Medio is visible beyond the trees in the center of the first frame; behind it is the caldera east rim, which extends across the second frame. At center of the second frame is Cerro la Jara, with South Mountain to its right in the foreground and extending across the last two frames.

After the Valles caldera formed in the great eruption of 1.21 million years ago, a ring fracture was left circling the interior of the caldera. This was a weakness through which fresh magma could force its way to the surface, forming ring domes around the caldera. Cerro del Medio was the first of these ring domes, forming very shortly after the caldera. Subsequent domes were erupted in counterclockwise order around the fracture, so that South Mountain and Cerro la Jara (both of which erupted around 520,000 years ago) are the youngest of the ring domes.

I continued up the trail, pausing to look at some tracks in the muddy road (possibly a shoed horse, a bear, and an elk, but too muddy to be sure) and checking out what I took at first for an outcropping of rock unusual for the area. I concluded I was looking at the mixture of random rocks typical of an alluvial fan, which this area is.

The trail came clear of the forest, only to plunge back in at the end of this valley. Looking back along the road:

Foothills of Redondo in left foreground; South Mountain in right foreground; beyond, Cerros del Abrigo at left and Cerro del Medio at right.

Cerros del Abrigo is another ring dome, with an age of 970,000 years.

Ahead, the road begins to climb more steeply, as we start up the narrow saddle separating South Mountain from Redondo

A branch of the road heads for South Mountain. Some other day.

I was puffing by the time I reached the top of the saddle.

It’s funny. When I was a Boy Scout hiking in the mountains, the possibility of a coronary seems not to have been on my mind. I always have a cell phone on these trips, and here it would likely have even gotten a signal, but it would take time to get me out. (True even if I was with a buddy.)

You can see some forest fire damage here. It’s patchy, but this is where the Las Conchas fire of 2011 swept through this area. Las Conchas itself is just the other side of South Mountain, and the fire started near there when winds downed a dead tree on power lines.

The road cut on the other side of the road exposes beds of El Cajete pumice.

Bits of this pumice were already visible in the trail up to this point, and here the dominate both trail and banks for the rest of the hike. We are close to the El Cajete vent.

The El Cajete pumice was the first of three closely spaced eruptions that mark the most recent spurt of activity in the Jemez. These are difficult to date; they are too young for the usual radiometric dating, but too old for cabon dating, while other methods are notoriously imprecise. However, 55,000 years is a reasonable estimate. The products of the first eruption are pyroclastics, mostly pumice but with occasional denser clasts of vesicular rhyolite and snowflake obsidian. Later eruptions produced ignimbrites (the Battleship Rock flow) and obsidian flows (the Banco Bonito flow).

It was about this time that I heard elk trumpeting in the higher ground to the right. “Trumpeting” is a strange word for it; it sounds more like a very loud kazoo. But there was no doubt it was elk; I could see them and tried in vain to get a photograph. Heading down the trail, I saw that there was quite a large herd (perhaps 15 animals?) on the lower ground to my left, heading up slope. I tried to get some photographs as they cut across the trail in front of me, but this was the best I could do.

You can see a couple in the photograph. I had a hard time with my little tourist camera; you press the button, it thinks about it for half a second, then snaps the photo. Makes timing hard.

I tried not to get too close. Elk are shy and usually nonaggressive, but if you get a bull elk riled, he’s going to get mean.

Los Griegos came into view from further down the trail.

This is the high point of the south rim of the caldera, underlain by hornblende dacite 7.5 million years old. It’s part of the Paliza Canyon Formation, which dominates the southern Jemez and accounts for more of the original volume of the Jemez volcanic field than any other single formation.

On the other side of the trail, the river channel is choked with debris flows:

Debris flows are composed of fairly large boulders carried along with enough water to make the whole mass fluid. This is a modern debris flow, created by the fire damage to the watershed here.

Hiking further, I reached the point where this channel crossed the road. There was significant damage.

The little voice in my head was saying: You may get down this section, but coming back up is likely to require some scrambling, and your shoulder is only a little more than two months out of surgery …

Of course, I went anyway.

While I knew where I had come from, and knew the way back, I was not 100% sure where I was. (The qualifier is to assure you that I was not “lost”). I wondered if the ridge to my right might be the lip of the El Cajete vent:

No. Shucks.

Yeah. I was starting to get tired and time was passing.

Continuing on down the trail, I ran into some real gulleys.

They’re real, and they’re spectacular. This section was at least ten feet deep, and it cut right across my path. I had to work upstream a modest distance to find a spot where I could cross.

Shortly after came a fork in the road; being too lazy to check my map, I headed right. It was comforting to have a sign confirm my choice a few feet down the road.

The road began winding steeply up the side of a ridge.

Notice the abundant pumice in the road bed. The road grade here must have been close to 30%, and I was wheezing by the time I got to the top. But not so wheezing that I failed to notice some beautiful snowflake obsidian.

My thought while on the trail was that this was Banco Bonito obsidian that somehow got on the far side of the El Cajete vent. However, my geologic map (the one I left at home by mistake) notes that obsidian clasts are found in the El Cajete pumice close to the vent. And we are very close to the vent here.

Obsidian is a black volcanic glass, formed when very high-silica lava solidifies too rapidly to form proper crystals. Snowflake obsidian is volcanic glass with clusters of cristobalite crystals, formed while the magma was still underground. Cristobalite is a high-temperature form of solid silica, but with a different structure from quartz; it is the stable form at 1470 C or higher. It persists in this obsidian because the transition to ordinary quartz could not take place before the crystals cooled to a temperature where the transition process is infinitesimally slow.

Also, as you will discover if you Google it, snowflake obsidian is believed by New Age types to be a mystical crystal that gives balance to body and mind. I didn’t notice my mind becoming any more balanced from seeing this stuff on this trip, and I think I actually tripped over a boulder of it a couple of years ago, so it hasn’t helped balance my body either. Color me skeptical of New Age.

Another bend and the road began to descend, and I could see the trees thinning out to the left.

And then…

The flat area is mostly alluvium, carried in by water after the vent formed, but there’s apparently a patch towards the center that is an original deposit of El Cajete pumice. There are also some deep pits in the far side of the flats, used as barbeque pits for guests when this was a ranch; Google shows them full of water so I didn’t bother to go look.

At left is a rim of pumice thrown up around the vent. At right is Redondo Peak. The low ridge in the third and fourth frames is the east end of the Banco Bonito obsidian flow. The vent for the El Cajete pumice is though to be directly under El Cajete flats, but the vent for the Banco Bonito flow is further west, not far from the edge of the flow seen here.

Well, cool. I ate my snack (a very large orange), rested for a few minutes, looked at my watch gosh look at the time, and turned around. I had no particular need to be back, except for not wanting to be rained on and not having brought a proper lunch; the latter was an oversight, the former prudent pessimism.

I started noticing more obsidian boulders on the trail back, and wondered about them. Could they have been thrown this far from explosion pits on the Banco Bonito flow? Too bad I didn’t have my geologic map to tell me that obsidian clasts, as well as country rock clasts caught up in the eruption, are sometimes found in the El Cajete close to the vent.

Though I had passed through before, I was struck by the extensive deposits of pumice on the valley floor here:

This seems like a nice modern example of sheetwash, where flood waters run across a large surface without being channeled. One for the book.

Some of the vesicular rhyolite here is impressive.

Vesicular rhyolite: Not bubbly enough to be pumice, not massive enough to be just plain rhyolite. The chunks I hefted felt like tuff. This chunk is larger than a basketball and is an impressive distance from the vent; given that it’s in a sheetwash deposit, and given the lay of the land, it probably originally landed even further from the vent. Impressive.

Back over the saddle (huff huff huff and my left hiking boot is digging into my ankle) and the welcome sight of the Valles:

Cerros del Abrigo on the left, Cerro del Medio on the right, and the clouds have lifted enough to show Tschicoma Peak framed between on the skyline. It’s the highest point in the Jemez and sits just beyond the Toledo embayment outside the caldera.

Here’s what a healthy ponderosa forest is supposed to look like.

The trees are widely spaced and surrounded by grassland. This is what you get if there are frequent “cool” ground fires to cut down the number of ponderosa saplings and promote the growth of grass.

Finally: Back to civilization!

More or less.

I got to the bunkhouse, got on my cell phone, and called for my ride. While waiting, I amused myself scanning the area with my big binoculars. The van arrived, I got in, and the driver entertained me on the ride back talking about how the vans functioned and how weird they are. I had never seen one with a pushbutton transmission before; he said it took some getting used to.

Checked in at the visitor’s center, confirmed that you cannot enter the Preserve at the old Banco Bonito staging area (shucks), and drove back to Los Alamos. Got some cash from the ATM (I need some to pay the young man who has been mowing my lawns this summer). Stopped at the library bookstore; nothing worth purchasing. Checked the stacks; there was a really nice book with paleogeographical maps of the Colorado Plateau, showing county boundaries; cool. Checked it out. Ate at the local McChinese. Got a new bulb for my car at the auto shop. Went home, installed it. Man, were my legs rubbery … Rested most of the rest of the day.

Today I repaired the single-lever ball faucet in my kitchen (my friend Robin R. has declared them the work of evil Chinese dwarves), cleaned the kitchen, got some posole going. Taking it easy and enjoying the day. I’m getting back to a regular schedule, though the shoulder is still sore, stiff, and weak. But getting much better.

Nice summary. I live just south of this vent, with my house built on the El Cajete pumice. We get there by going straight across the East Fork near the cliff jumping spot.

I sent you a private message via Facebook to ask if you have ever Wanderlusted Forest Road 181/American Springs Road. It doesn’t look like the message I sent has been viewed yet so I thought I’d try reaching you through your blog.

I don’t see your message at Facebook; I’m not sure why. I haven’t visited American Springs, though I’ve driven past countless times; I may make it a side trip sometime, though.

Here it tis from August 2:

“Hi Kent,

Have you ever wanderlusted forest road 181, aka, American Spring Road (right across NM4 from the Apache Spring trailhead)? I was just there today. It’s one of my favorite roads to walk. Last year, with all the rain we had, Apache tears were washing out onto the road in the area where the main Water Canyon branch crosses. I even found an obsidian arrowhead uphill and past Water Canyon. This year, there’s not so much Apache tears since we haven’t had a lot of rain to wrest the obsidian from the soil but I did find a few places today, maybe thanks to our recent rains. So, I wonder where the obsidian is coming from? The area is below an eastern arm of Cerro Grande. Any wanderlust here would also have to include the stunning cliffs above the main branch of Water Canyon! To further whet your interest, there are springs just off the road – American and Armstead. Plus, there’s a spring in the easternmost branch of Water Canyon that once supplied water to S Site.

Glad you are on the mend after your surgery!

Yvonne”