The Alternative Wanderlust

Perhaps I should have taken a break this weekend, but the weather was again forecast to be gorgeous and the back country season in the Valles Preserve is fast coming to a close.

So I devoted Friday to catching up on all my chores, so that I could enjoy a guilt-free Saturday in the mountains. It was tough, seeing the beautiful morning passing while I worked around the house, but it helped that I at least got to sleep in first. Plus the weather deteriorated more than expected late in the afternoon, so at least I had been spared dealing with that.

Then Cindy and I went grocery shopping in Santa Fe. (The WalMart in Espanola is closed for remodeling.) We decided to eat out as part of it, something we haven’t done in a while. Then we found that finding our way around an unfamiliar WalMart was time-consuming. And we needed more stuff than we realized. And then it took a full half an hour to bag our groceries at checkout, because Santa Fe has this useless and aggravating ordinance requiring stores to charge for bags unless you bring your own, and Cindy had brought our recycled bags. With all the will in the world, this is still vastly less efficient than the use of identical plastic bags prepositioned on a turnstile. This is the real cost of bag ordinances: Not the cost of the bags themselves. The cost in wasted human effort.

Upshot: We didn’t get home until 10:00 PM, and then we still had to unload the groceries.

And then, around 1:00 in the morning, we had the first really spectacular electrical storm we’ve had all season. Which I had a hard time sleeping through just on general principle, but especially because my little dachshund, Laci, is terrified of thunder and was scratching at the door of her kennel for a full expletive hour. I sat close to comfort her, and it helped a little, but of course that kept me up.

So I was later than I liked getting up Saturday morning, and by the time I got organized and up to the preserve, they had already issued all their back country permits for the day. Shucks.

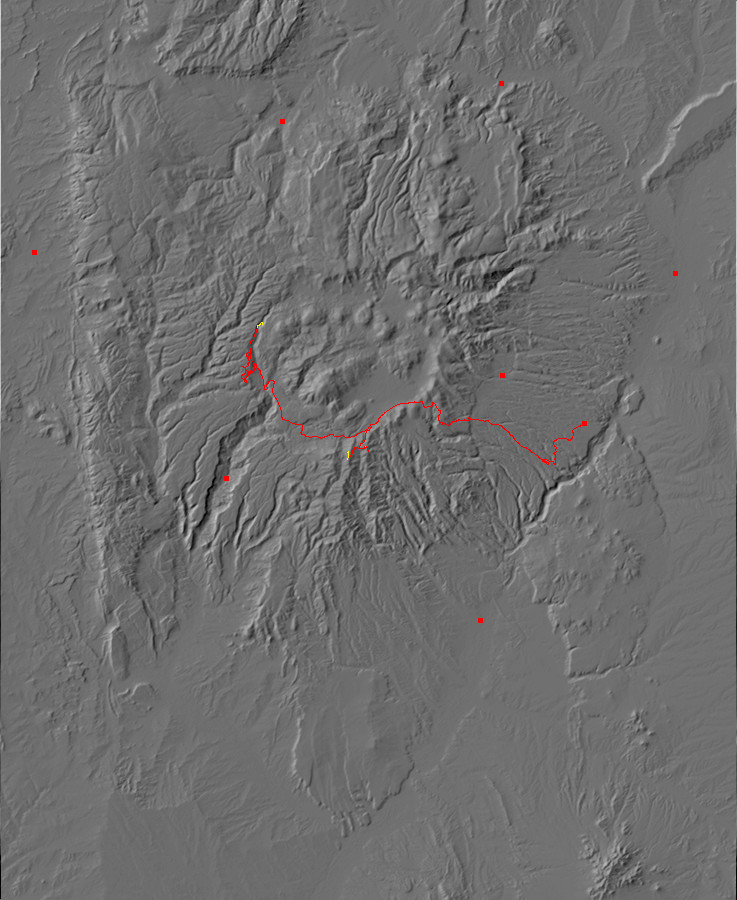

My backup plan was to explore the western rim of the caldera. I started that way, but, on impulse, turned onto Forest Road 208 and headed down into Peralta Canyon. I had some vague notions of looking at the Bandelier Tuff beds in the canyon, revisiting the hydrothermal breccia outcrops, and perhaps climbing that knoll I’d been too tired to climb Monday.

FR 208 passes over the rim of the caldera, then turns right to climb up the east side of Peralta Ridge. At one point it passes outcrops of Tsherge Member, Bandelier Tuff.

The presence of these beds here, and of both Tsherige Member and Otowi Member further down the canyon, show that Peralta Canyon already existed when the Toledo caldera collapsed 1.65 million years ago. The canyon bottom was filled with Otowi Member, which subsequently mostly eroded away, and then the canyon bottom was filled again with Tsherige Member when the Valles caldera collapsed 1.21 million years ago, which has also mostly eroded away.

I passed what turned out to be the forest road down Peralta Canyon. The road looked unused, being overgrown with grass and with a sign directing travelers along Forest Road 208 to the right. I decided not to chance it, though Google suggests the road is not that bad. I found myself going up the side of Peralta Ridge instead. Excitement! Adventure! I had no idea where I was going!

But the views looked very promising, so I kept on, and gradually a plan formed in my head to climb to the top of a high knoll I could see to the south from the road here

from which I could get a very nice panorama. I reached the crest of the ridge, where I found another car parked, saw that the road apparently descends into the next canyon (upper Paliza Canyon, as it turns out) and decided this was a good place to commence my hike.

That’s a cattle guard across the road, with barbed wire fence heading north and south along the ridge crest. Again, on impulse, I decided to hike north along the fence, which had fairly easy ground to either side. It seems that game and cattle tend to wander along fences, forming what amounts to a game trail on either side.

This turned out to be an excellent decision, considering it was made on impulse. The going was fairly easy and there were some very nice views. For instance, Los Griegos, the high point of the south caldera rim, was visible to the west.

Notice the cliffs halfway down the slope. These continue to the south at a slightly higher level. If I’m reading my geologic map correctly, this is a late basalt flow of the Paliza Canyon Formation (which underlies most of the terrain south of the caldera) with an age in the ballpark of 9 million years old. I describe it as a “late” flow because most of the basalt of the Paliza Canyon Formation is found at lower stratigraphic levels; this flow is separated from these flows by a fairly thick sequence of andesite.

The fence wandered west down the ridge, and I paused for a photograph of Redondo Peak beyond.

It was time to leave the fence and head up the knoll. This was composed of a very pretty hornblende dacite.

The dacite is choked with white plagioclase phenocrysts. This thick mush of crystals in a viscous matrix would have had considerable difficulty just emerging from its vents, yet it is present both here and on neighboring Los Griegos.

A little higher, and I had a clear view to the west.

Los Griegos is to the left and Redondo Peak to the right. Beyond is the spectacular cliffs of Bandelier Tuff of Cebollita Mesa on the west side of Canon de San Diego. In the middle distance in front of the cliffs is Banco Bonito, a very young (~55,000 years) obsidian flow. On the skyline are the Sierra Nacimiento Mountains, with Big Mountain near the center of the panorama. Unlike the Jemez Mountains proper, the Sierra Nacimiento Mountains are fault block mountains of Precambrian granite and metamorphic rock thrown up by the Laramide Orogeny, 60 to 30 million years ago. They were likely the original west rim of the Rio Grande Rift in this area, but deformation associated with the Rift seems to have shifted east to the Pajarito Fault, just west of Los Alamos, within the last few million years.

Ahead, a knoll from which it looks like I will have a very nice view.

Turns out this is not the furthest north knoll of the ridge, which is actually Conchas Peak.

Meh. Too many trees, and the lighting is wrong to the west. But Conchas Peak is there just to the north (second frame), and its top is practically bare of trees. The temptation is strong with this one…

The saddle I’d have to hike along was rather steep and overgrown, and I decided it would not be prudent. Which was probably prudent, but I’m almost wishing now I had done it.

I took another panorama from a slightly different vantage point but only its central frame was a keeper.

Redondo Peak, second highest point in the Jemez, in all its glory. Redondo Peak is part of a resurgent dome, formed when the caldera floor was pushed back up by fresh magma injected into the magma chamber very shortly after the Valles eruption. The entire process took perhaps as little as 50,000 years.

The meadow patch just south of the mountain, partially obscured behind a ridge line, is El Cajete, the source vent for the El Cajete Pumice 55,000 years ago. The source vent for the Banco Bonito obsidian is just to the west in the forested area. The meadow between the two cloud shadows, left of center, is an old pumice strip mine, with State Road 4 just to its south.

Having decided I could not risk the further climb to Conchas Peak — I was, after all, already well off my original flight plan — I headed back. Along the way I photographed an illustration of a sometimes little-appreciated agent of rock weathering.

Fire.

This area has recently been burned over, and the rocks often show signs of soot. What’s more, many appear to have shed an outer layer (exfoliated) from the heat of the fire. I wonder if this isn’t a significant cause of weathering over geological time scales in an area where natural wildfires are a regular occurrence.

A little further down the trail, and we leave the cap of hornblende dacite atop this part of the ridge. The rock here is two-pyroxene andesite around 8.8 million years old.

I hiked back to my car, ate my orange, and then hiked south along the barbed wire fence. This was shorter and easier going, and in no time I was approaching the knoll to the south. From which I had a nice view all the way into the Toledo Embayment.

Alas, lots of low cloud and there are trees in the way; not one for the book.

Climbed atop the knoll, and found a nice view to the east.

Aspen Ridge stretches across the entire panorama, with Peralta Canyon in the foreground. Cerro Pico and Cerro Balitas are visible in the distance near the center of the panorama. The knoll at left conceals the point from which I will be taking some spectacular panoramas later this day, while the prominent knoll at the right edge of the next to last frame is Woodard Ridge. The high knolls in the final frame make up Bearhead Ridge (not to be confused with Bearhead Peak further south).

I shifted position slightly, and got a panorama to the north.

Alas, still a few more trees in the way than I would like. Still. Redondo Peak to left, Conchas Peak just left of center, Valle Grande peeking over the caldera rim right of center, and the north part of Peralta Ridge to right.

Here’s a close up view of part of the third frame.

If I’m reading my geological map correctly, the cliffs above center are part of the same basalt flows of the Paliza Canyon Formation that we saw earlier on the east flank of Los Griegos. They’re at a lower elevation here, because the Paliza Canyon Fault has thrown down this area relative to Los Griegos. Most of the canyons of the southern Jemez appear to be structurally controlled; that is, they are aligned with major faults, which produce a zone of crushed rock that is susceptible to erosion.

Coming down off the hill. Little lonely car in the distance.

Yeah, I know. The Wandermobile is such a rugged vehicle, by comparison, that it just doesn’t work to anthropomorphize it in the same way as Clownie the Wonder Car.

It was barely noon. I headed down Peralta Ridge and took the turn to Aspen Ridge, planning to take another look at that area mapped as hydrothermal breccia. I recalled vaguely that the geologic map, which I had not brought with me, showed that a side road passed right over one breccia pipe, so I parked and started hiking down the road.

Could this be it?

No, probably not. The location is not quite right and this looks like just an isolated patch of hydrothermally altered andesite, like you find all over this area.

How about this?

Again, probably not. A careful comparison of my position and the geologic map says this is hydrothermally altered andesite very close to the Aspen Ridge fault. In fact, it looks like at this point I had already walked right past one patch of hydrothermal breccia, and, as it turns out, I quit here, some distance short of the place in the road that appears to pass right over a hydrothermal breccia pipe. Well, I have a pretty good idea where to look next time.

In fairness, what I am looking for is mosaic breccia cemented with silica, and this

maybe kinda does look like very poor mosaic breccia, if you squint at it right and think wishfully enough. Still. When I cracked open another “breccia” shard, I saw:

The interior of the shard looks to be relatively unaltered andesite, with a coating of iron oxides and silica. Shucks.

Not knowing I was too far south for the one patch, but thinking that what I had found was not quite convincing, I decided I’d look for another patch mapped further south. But first I wanted to climb that knoll, the one I was too tired for Monday, and get a good panorama. I went up the southeast side, and while there was a lot of scree to scramble over and some brambles, it really wasn’t too bad. And the view from the top was wonderful.

The panorama begins to the west, and Aspen Ridge extends across the first four frames. You can see the road I came in. Redondo Peak forms the skyline in the third frame, and Cerros del Abrigo and Cerro del Medio are visible in the fourth frame, with the north caldera wall behind. Rabbit Mountain dominates the fifth frame. On the other side of the foreground trees, we see the San Miguel Mountains in the distance in the fourth to last frame, with mesas of Bandelier Tuff in the nearer distance. The third frame from the left looks almost directly down Bland Canyon. The last two frames look down the southern part of Aspen Ridge.

Unsurprisingly, there was a cairn at the top of the knoll, and a piece or two of trash.

Some close up views. The wild country southwest of the San Miguel Mountains:

The view towards Boundary Peak:

I worked my way back down the knoll, ate lunch, and headed north to try to find the other patch of hydrothermal breccia. Again, I think I was looking in not quite the right place. At one spot, I came across what looked very much like Bearhead Rhyolite:

This spot appears to be too far southeast. I worked my way a little north, and found myself apparently tracing a small dike of Bearhead Rhyolite.

However, this position appears to be still too far south and east.

I’ve now very carefully plotted the coordinates of the two patches of hydrothermal breccia from the geologic map, and we’ll see if third time is lucky.

Heading back over the caldera rim, I found the view demanded another photograph.

Cerro la Jara at center. In front of Cerro la Jara, an early South Mountain flow. Behind, the large dome is Cerros del Abrigo, with the lower Cerro del Medio at right. Behind, the north caldera wall.

And a nice view from here of South Mountain.

Still had plenty of time and the weather was actually improving. I set out for the west caldera rim.

Of which I took a panorama from here.

The most noticeable thing about the west rim is that it is lower than the south, north, and east rims. Gravimetric readings confirm that the caldera floor collapsed to a greater depth on the east side of the caldera than the west. Geologists call this a trap door caldera.

I continued up State Road 126, taking the turn north onto Forest Road 376. The southern part of this road is one of the better gravel roads in the Jemez; the north part starts off rough enough that I chickened out last time I was here, driving Clownie. This time I figured the Wondermobile could handle it and just plowed through. And, for the most part, the road was okay.

I watched for interesting outcroppings along the road, which slowly descends the west caldera rim as it heads north. Like this one.

This turned out to simply be colluvium rich in Bandelier Tuff clasts, judging from the geologic map. A little further down was this:

This is mapped as Ts, undivided Tertiary sediments. These make up a fair part of the west caldera wall, and this section must be at least five million years old. The authors of the geologic map seem not to know quite what to make of it, though it likely should be assigned to the Santa Fe Group of rift fill sediments.

Coming around a corner, one sees a dramatic view of the west side of San Antonio Mountain.

Not too much further along, one encounters Permian rocks of the Abo Formation at the base of the caldera rim.

These long predate the Jemez volcanic field, being around 310 million years old. Their presence establishes that San Antonio Canyon is outside both the Toled and Valles ring fractures.

The road ends with a parking area and a locked gate, here.

No motor vehicles beyond this point. Shucks; there’s some geology up there worth looking at. But it may be accessible, perhaps with some hiking, from Forest Road 144.

There is some excellent scenery.

The cliffs are Otowi Member, Bandelier Tuff, except for an isolated patch of Tsherige Member forming the high point of the rim. In general, the beds of the Otowi Member are best preserved on the west side of the caldera, where the Tsherige Member is fairly spotty.

The west face of San Antonio Mountain:

San Antonio Mountain is a ring dome, formed from high-silica magma that welled up along the Valles ring fracture almost exactly a million years ago. The dome likely flowed right up against the caldera rim here, creating a lake in the northern caldera whose lake beds have been mapped by geologists. The lake eventually eroded an outlet in this area, leaving high cliffs on both sides.

Here’s San Antonio Creek, the agent of that erosion.

Seems pretty harmless, no? They say it’s always the little guy you have to look out for.

A clast of Bandelier Tuff (probably Otowi Member) in the road bed.

Note the many bits of rock embedded in the tuff. These were torn from the walls of the vent through which the tuff erupted.

I cross San Antonio Creek and started up to the springs. Here‘s a view of a dramatic outcrop of Otowi Member on the west cliff.

Approaching the springs. The runoff is considerable.

I did not photograph the springs themselves. They were crowded with people, and I avoid including strangers in my photographs; it seems intrusive. Especially when it’s people in various states of undress.

But I did take a pan of west caldera rim from the springs location.

While in the area, I grabbed a sample of the rhyolite of San Antonio Mountain.

It’s fairly typical of the ring dome rhyolites, having lots of glassy quartz crystals.

Some larger boulders of this rock were along the trail back out.

You can see flow banding in these rocks.

I hiked a little further up Forest Road 376. This continues well up the canyon and onto the Valles Preserve — though the gate there is closed and heavily barred.

The bank to the left caught my attention. Further down it became a substantial bed in the road cut.

It looks like a tuff, but it’s very poorly consolidated. The geologic map maps this area as colluvium, but shows a bank of Otowi Member just up the hill. So this is reworked tuff, formed from sediments eroded off the original tuff bed.

Time to start back. There were some pretty enough Abo beds along the road for another photograph.

I hiked to my car and started back to the main highway. As I said, there were a couple of bad spots in the road; this one I just have to share.

I kept a lookout for interesting outcrops in the road cut again. Such as:

This looked like basalt, but the area is mapped as Tertiary sediments. However, the stratigraphic position corresponds to Paliza Canyon basalt, so that’s probably what this is.

Also basalt, but this time the location is right at the edge of a mapped Paliza Canyon basalt outcropping.

I did not ignore some of the wonderful views from the road.

Redondo Peak, with Redondo Border in front and, in the middle distance, Thompson Ridge. To the right, peeking through the trees, is the south caldera rim and the mouth of Canon de San Diego.

And now an outcrop I had been hoping to spot:

Up in the trees, well above the road, is a flow of Tschicoma Formation dacite. This extends along much of the caldera west rim. I scrambled up for a closer look.

Massive boulders broken off the face of the flow.

The eroded face of the flow.

The flow has a massive core over a base of breccia.

The breccia is quite solid, in spite of its appearance. It represents fragments broken off the face of the very viscous dacite flow as it advanced, which formed a carpet of broken rock beneath the more massive core of the flow.

The Tschicoma Formation underlies most of the Sierra de los Valles that makes up the western skyline of Los Alamos. It is mostly dacite, a rock moderately high in silica, most of which has a radiometric age between 5 million and 3 million years. The presence of recognizable flows of this formation on the west caldera rim suggests that the Sierra de los Valles is just the easternmost part of an extensive field that extended across what is now the Valles caldera.

Samples. First, from the breccia at the base of the flow:

From the massive core of the flow:

The latter is quite striking, isn’t it? The larger white crystals are feldspar, while the smaller include quartz, and augite and biotite crystals are prominent under the loupe.

It’s also striking that the two look so different. The base sample has a glassy appearance under the loupe, suggesting more rapid cooling consistent with this being formed on the face of the flow. There are also hints of microscopic glass bubbles.

I headed back onto State Road 126, turned right, and proceeded to Forest Road 144. Sometime I will make a day of exploring down this road, but for now I was interested in a lookout point that I reconnoitered last year but in bad weather for photography. Weather was no problem today.

San Antonio Mountain at center, with the prominent cliffs on the east rim of San Antonio Canyon across the frame. The distant mountain on the skyline at the center of the left frame is Cerro Pelon on the La Grulla Plateau.

I headed home, but with one last photograph along the way.

This one is for the book. The low ridge, located just north of State Road 4 as you approach Sulphur Creek from the east, is one of the more accessible megabreccia slabs in the caldera. The ridge is essentially a single large slab of Paliza Canyon Formation lava that broke off the caldera rim as the caldera collapsed, sliding down onto the caldera floor where we see it today.

And finally home.