Wanderlusting the Nacimiento Mine

This trip was with the Los Alamos Geological Society. Also the PEEC Pebble Pups and the Albuquerque Gem & Mineral Club Junior and Pebble Pups. This made for a very large group. The group from Los Alamos alone was sizable.

That’s our group, stopped along Route 126 deep in the Jemez for a potty break. (Gentlemen to the front, ladies to the rear.) For some reason I found myself singing “We Got A Great Big Convoy” in a high falsetto voice in my car; fortunately, no one had taken me up on the offer of a ride.

Parking at the Nacimiento Mine.

We were briefed by Larry Gore, geologist with the USDA Forest Service, who was our primary host. The mine has been worked since at least the 19th century, originally by adits (horizontal tunnels) in the copper-bearing beds. These were shut down during the First World War, due to the wartime labor shortage, and never reopened. Open-pit mining began in the 1960s and continued to 1975, when rich new copper deposits in South America began to be worked and drove the worldwide price of copper so low that the Nacimiento mine could not longer be profitably worked.

In 1984, an attempt was made to extract the ore by in-situ leaching using a solution of sulfuric acid. However, the method proved uneconomical. By then some 25,000 gallons of sulfuric acid had been pumped underground. This posed a serious environmental hazard, and in 2007 the Forest Service began remediation, flushing fresh water through the ore body to remove the acid waste and processing it in a series of treatment ponds on the site. The water returned to the watershed is apparently so cleaned up that it meets drinking water standards.

The treatment ponds begin with an anaerobic pond, filled with boulders, in which alcohol is added to feed anaerobic bacteria. The bacteria convert the sulfuric acid in the leach water to hydrogen sulfide, which precipitates out most of the metal contaminants but gives a distinct stench to the area. It was not too bad this day.

Our trip was a last-chance visit. Next year, work will begin to gather and bury the mine tailings, which are the best source of specimens for the rockhound but which are themselves an environmental hazard.

We proceeded on down to the main mine area, where our LAGS host, Patrick Rowe, told us what to look for and where.

That’s the main mine pit in the background. There is an active claim at the north end fo the mine pit, held by an Albuquerque rockhound, which Patrick warned us to respect. Patrick let us see some samples, including this large piece of petrified wood with copper mineralization and a cut and polished septarian nodule.

The septarian nodule is at the top of the photograph. It contains numerous cracks (septaria in Latin) that are now filled with mineral crystals, in this case probably calcite and barite. The petrified wood is the black material in the bottom sample, and the green and blue material is the copper mineralization. No, I didn’t find a sample like this; this is nearly a museum-quality specimen.

Most copper mines consist of copper sulfides deposited by hydrothermal activity, with a rich cap of copper carbonates (green malachite and blue azurite) formed by oxidation of the upper part of the ore body. The Nacimiento Mine is one of a very few copper mines in the world in which copper was deposited by groundwater in a carbon-rich sedimentary bed. The copper was leached from overlying beds of the Chinle Group by the groundwater, which then percolated through the underlying sandstone of the Shinarump Formation (formerly called the Agua Zarca Formation.) The presence of organic matter (petrified wood) provided carbon, which produced a low-oxygen environment in which the copper was precipitated primarily as chalcocite, a copper sulfide mineral, and as smaller quantities of malachite and azurite, copper carbonate minerals.

The most striking copper minerals at the Nacimiento Mine are vivid green malachite and blue azurite. Malachite is much more common, in part because azurite slowly changes to malachite when exposed to air. The petrified wood itself has had a variable amount of its carbon replaced by chalcocite; the two can be hard to distinguish, since massive chalcocite is black in color.

The septarian modules form in the red beds of the Salitral Formation that overlie the Shinarump Formation. My impression is that their mechanism of formation is not very well understood.

Another geologic curiosity found at the mine is pyrite nodules, which are most common in the Poleo Formation overlying the Salitral Formation. I did not find any, nor did very many others on the trip, and I neglected to photograph Patrick’s sample.

Patrick pointed us at the main tailings dump, where the pickings were easiest, and off we went.

I had already slathered on the sun screen, something pretty much compulsory with me since I had the skin cancer removed a month or so ago. Consider that your public service announcement for the day: Protect yourself from the sun, and have unusual skin lesions checked promptly. I spotted mine right away and it was removed at once, which probably saved me from going by the name “Vincent” for the rest of my life.

The tailings consist of overburden, which is coarse rock removed to get at the ore body, and gangue, rock within the ore body that was ground to powder and separated from the ore during milling. It’s not hard to tell the two apart, and the gangue could be expected to be devoid of ore. The best pickings were in the coarse overburden.

My first find, not quite rich enough to go in the bag.

You can see how the copper mineralization tends to be close to black fragments of petrified wood.

A youngster having the time of his life digging up a promising green rock fragment.

Some nice green malachite covering a sandstone surface. This, too, was too large for my bag. In fact, I didn’t photograph a rock unless I was not going to take it with me.

Would like to have taken this one with me, but just a little too large.

Numerous bits on the ground. The mother lode?

Another too-large-for-the-bag boulder encrusted with malachite.

I’m guessing these kinds of deposits formed downstream from a bit of petrified wood along an existing fracture in the rock.

A couple more:

I had a rather full bag by this point. I dumped out my specimens and decided which were “leaverite” and which were keepers. Here are my keepers.

Here’s one that can serve as a yard rock.

These next two are nice because they have a fair amount of blue azurite in them. Azurite is distinctly less common than malachite, in part because it tends to slowly convert to malachite when exposed to air.

A collection of petrified wood fragments.

I may give some of these away. I have a nephew who is, or at one time was, interested in geology. I also offered one to Cindy.

Me bring girl-thing pretty rock.

Alas, while she is wonderful about letting me explore the hills, she hasn’t that much interest in geology herself. She’s more a molecular biology type.

This one, though, I am not giving away.

It’s not a large fragment, but in addition to having beautifully preserved grain, you can see that there is some kind of membrane or layer cutting across the grain at intervals of a few millimeters. I am not paleobotanist enough to tell you the significance of this, alas, but it might identify the species. The fragment is relatively heavy, suggesting that much of its carbon content has been replaced by chalcocite.

I ate lunch, then walked over to a convenient overlook for the old mine pit.

The mine pit is now filled with water, the top layer of which is little more contaminated than normal groundwater. (The deeper parts of the lake are another matter.) You can see white beds of Shinarump Formation on the far side of the lake, overlain by red beds of the Salitral Formation of the Chinle Group, which are also visible to left and right. The geology is a little weird here, and I had to study the geologic map for awhile to get it straight in my head. The rock beds in this area are all steeply tilted to the west, due to the nearby Nacimiento Fault, so rocks further to the west are younger than those to the east. The many small white buildings are part of the well system for the reclamation project.

I hiked along the benches to the right, and found a really impressive outcrop of sandstone.

Look at how thinly bedded this is. My best guess after perusing the geologic map for this area is that this is an outcrop of Poleo Formation, which is stratigraphically located above the Salitral Formation. This in turn is overlain by upper Chinle shale, probably of the Painted Desert Formation, which forms the reddish terrain west of the mine pit.

I continued around the mine pit, pausing to look over some of the soft red shale exposed here. A family of fellow geology enthusiasts were happily cracking rocks; well, this was the kind of beds we were told to expect septarian nodules in. Looking around, I found a likely-looking candidate and gave it a crack with my geologist’s hammer.

Yup. Not a great specimen, though. (Then again, if it had been, I would be slapping myself upside the head for ruining it with my hammer.)

I grabbed another large candidate, gave it a good crack with a hammer, exposed some interior crystals, and finally engaged my brain. This one looked like it might be a great specimen. I collected a couple more likely candidates and stowed them in my pack. These I plan to have sawed in half, if I can find someone with a rock saw. (My own budget won’t afford one any time soon.)

I continued on around the pit, coming across a large boulder of Shinarump.

Note the softer layer between the two harder beds. This turned out to have some petrified wood, but no visible copper mineralization.

Here’s the east face of the mine.

Note the large concrete anchors for steel cables. I don’t know enough about mining to be able to tell you what these were used for. Note also a few splashes of green.

Here’s one close up.

This shows what the ore deposits were like before being mined. There is a large fragment of petrified wood surrounded by malachite. I was not inclined to try to chip out anything like this.

Another example:

Now this is interesting:

This layer of the formation is thick with petrified wood, but there is no visible copper mineralization. This petrified wood was also distinctly lighter in color than was typical of fragments surrounded by malachite, suggesting that there has been relatively little replacement by chalcocite. Petrified wood must be present for the mineralization to take place, but not all petrified wood actually yields mineralization. I don’t know why.

I also don’t know what produced this layer of petrified wood. The wood would have to have been deposited in the sediments in quantity in a fairly short time, then quickly buried under more sediments before it could decay. Flood? Forest fire followed by a flash flood? Volcanic eruption?

This is probably bioturbation.

Bioturbation is disturbance of a bed of sediments by living organisms, such as burrowing worms. I’m guessing some kind of burrowing animal here as well. Again, I’m not paleontologist enough to make a more specific guess.

Finally, a view of the lake from the other side.

The lake is accumulated ground water, which has no outlet here. Dealing with the constant influx of groundwater was one of the expenses that originally drove the mine out of business in 1975.

The near side of the lake is Shinarump Formation overlain by Salitral Formation. The Poleo Formation runs along the west side of the lake, though it is poorly exposed, and the red high ground beyond that is probably Painted Desert Formation. The skyline ridge may be Jurassic Entrada Formation cut by the Nacimiento Fault, and beyond that are more Jurassic and Cretaceous beds.

I was disappointed to not find any pyrite nodules, but few of us did. One of the other participants did find a nodule cemented with native silver; I almost grabbed my pack and headed out to find one for myself, but our time was up. I signed out and started back.

I had not stopped on the way out (except for the potty break) so that I could keep up with the convoy. I was on my own on the way back, and took the opportunity to see some northwest Jemez geology. This is the part of the Jemez I know the least well.

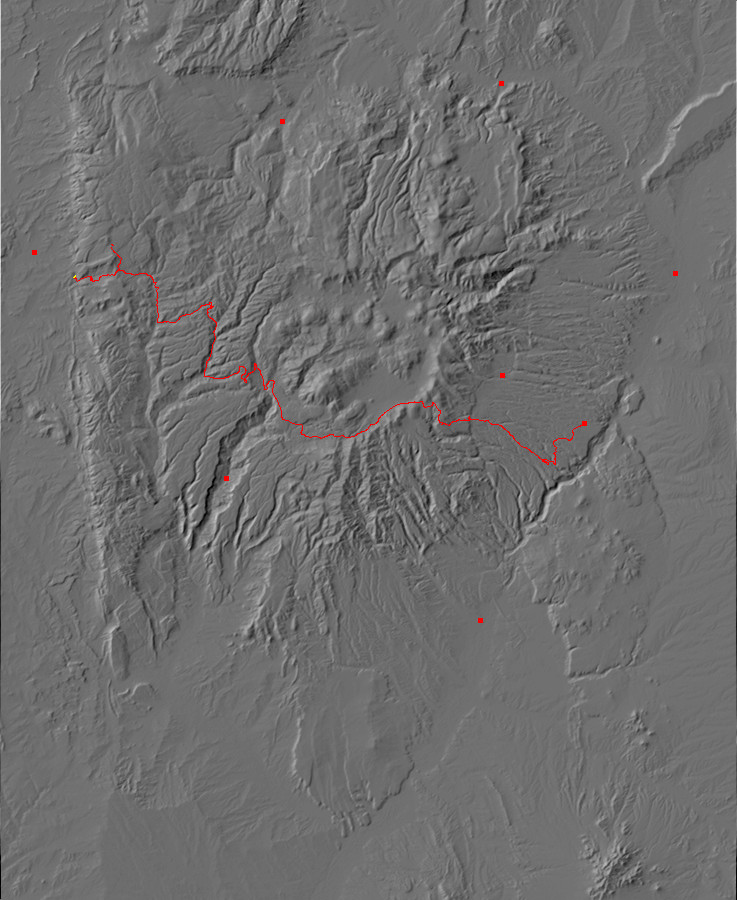

The Nacimiento Mine is located at the west end of Eureka Mesa. Here a couple of views of the mesa, from here

and here.

The mesa is capped with Shinarump Formation, which is quite level east of the Nacimiento Mine before it starts to dip into the Nacimiento Fault. Underneath are beds of the Permian Yeso and Abo Formations.

I came to the forest road leading to the trailhead for San Gregorio Lake and the San Pedro Parks Wilderness. Well, heck. One of the most enjoyable Scout camps I ever had as a teenager was at the lake, but I had never been back. Plus, the geologic map for the area showed a fairly cool kind of granite called rapakivi granite. I turned onto the road, and after driving some distance, came across some obvious granite.

I did not notice the rapakivi texture at first. I was more struck by the numerous crystals of bluish quartz; quite unlike any other granite I had seen.

The outcrop had a shear zone crossing it.

And a big patch of more mafic (silica-poor) rock.

This is probably not a dike; it’s too localized. It looks like a big blob of country rock (the rock into which the granite was intruded) that broke off and sank into the granitic magma.

I keep saying granite. This is actually quartz monzonite, which differs from true granite in having more plagioclase feldspar and less akali feldspar.

I checked out another outcrop to the south, and this time the rapakivi texture was clear.

The weathering of this surface helped bring it out. Here’s a sample.

The rapakivi texture refers to the big pink rounded crystals. These are orthoclase, a form of alkali feldspar, with a rim of oligoclase, a sodium-rich plagioclase feldspar. You can see the rim particularly well on the big crystal towards the right side of the sample. The presence of big, fat, and happy orthoclase crystals makes this a rapakivi quartz monzonite; the oligoclase rims makes it the particular kind of rapakivi called vyborgite.

Rapakivi texture is fairly rare in granite-like rocks, so it’s kind of cool we have a very large exposure of this rock so close to home. This texture is usually associated with granite-like rocks that were not formed during a continental collision, the so-called A-type or anorogenic granites. There was a very widespread pulse of anorogenic granite formation in western North America 1.4 billion years ago; I’m taking a wild guess that’s how old this rock is.

I returned to Route 126 but stopped again to look at a mafic dike intruding another quartz monzonite outcrop.

Turns out this one is on the map. A close examination showed something I’ve never encountered before.

There are rather large crystals of orthoclase in the otherwise fine-grained dike rock. These look like the distinctive orthoclase crystals of the rapakivi quartz monzonite. A sample:

Furthermore, while washing the sample to prepare it for its portrait, I realized that there are bluish quartz grains in the rock that are elongated in one direction. (You can see one just above the center of the sample.) I’d never seen or heard of anything like this. Some online research suggests that this is a kind of lamprophyre called vogesite. The geologic map for this area indicates that lamprophyre dikes are present in the quartz monzonite. So there it is.

Lamprophyres are very low-silica, high-potassium rocks formed in small volumes by very slight melting of the earth’s upper mantle.

A little further down the road I passed the Great Unconformity, which separates Precambrian rocks from Phanerozoic rocks, and found myself looking at a very pretty outcropping of the Pennsylvanian Madera Formation.

Just too nice not to photograph.

From there it was Bandelier Tuff and familiar ground, so I proceeded on home. Not a bad way to spend a Saturday.

Pingback: Earth Treasures Show 2017 | Wanderlusting the Jemez

Hello! Great blog post. Was there any discussion as to the family, genus, or species of plants fossilized in chalcocite at the Nacimiento Mine?

I’ve seen no identifications of specific plant taxons.

Kent, is there any sort of permission needed to rockhound around the Nacimiento Mine? Or is it simply considered part of the national forest?

I’m afraid it’s closed for remediation. Our trip was possible only through special arrangement. I’m not sure how one goes about that; our club field trip organizer took care of that.