Wanderlusting the Valles north rim

Today was the first day of this season in which I had the whole day open, the Valles Preserve was issuing back country permits, and the weather was forecast to be excellent. So I decided this would be the perfect day to go and repeat some panoramas with my new camera that hadn’t come out so well with the old. This would require getting up at 6:00, in order to be at the headquarters when it opened at 8:00, but sometimes you have to make sacrifices.

So I awoke at the appointed hour (how do our brains know? I almost invariably wake up just before the alarm is due to go off, even when it’s not set to the usual time. This time I woke up at precisely 5:59 and got to the alarm clock just in time to turn off the alarm before it went off. Go figure.) I made breakfast, loaded up a sack lunch, got my backpack and camera and spare batteries and stuff, and was on the road by 7:10. The drive was fairly uneventful, over very familiar country, and I was at the headquarters by 7:50.

You can see what a beautiful day it was shaping up to be. I noticed that the headquarters had several swallow nests, including one right under the peak of the roof that looked occupied.

You can’t see any birds in this photo, but the adult birds were visiting the nest periodically. I assume there’s some brood in there that keep out of sight when the parents are not around. And prairie dogs:

There’s a small colony just west of the headquarters building, and several fat prairie dogs were in view.

I got my permit and headed towards the caldera north moat. Again, this was mostly familiar country, so I did not pause for pictures before parking near the Cerro Trasquilar dome, donning backpack and grabbing walking stick, and heading out.

That’s the Wandermobile at the parking area, with the Cerro Trasquilar dome in the background. This dome has an age of about 1.36 million years, meaning it formed between the Toledo caldera eruption 1.61 million years ago and the Valles eruption 1.22 million years ago. It is interpreted as a ring facture dome, formed when lava erupted through the ring fracture where the caldera floor collapsed in the Toledo event.

The road ahead.

This is looking almost straight west down the north moat of the caldera. This is the low ground between the caldera north rim, to the right, and the circle of ring domes to the left. These ring domes erupted along the ring fracture of the Valles event. At farthest left is part of Cerro Santa Rosa, erupted 900,000 years ago; to its right and at increasing distance are Cerro San Luis and (800,000 years) and Cerro Seco (790,000 years). In the far distance is the west caldera rim.

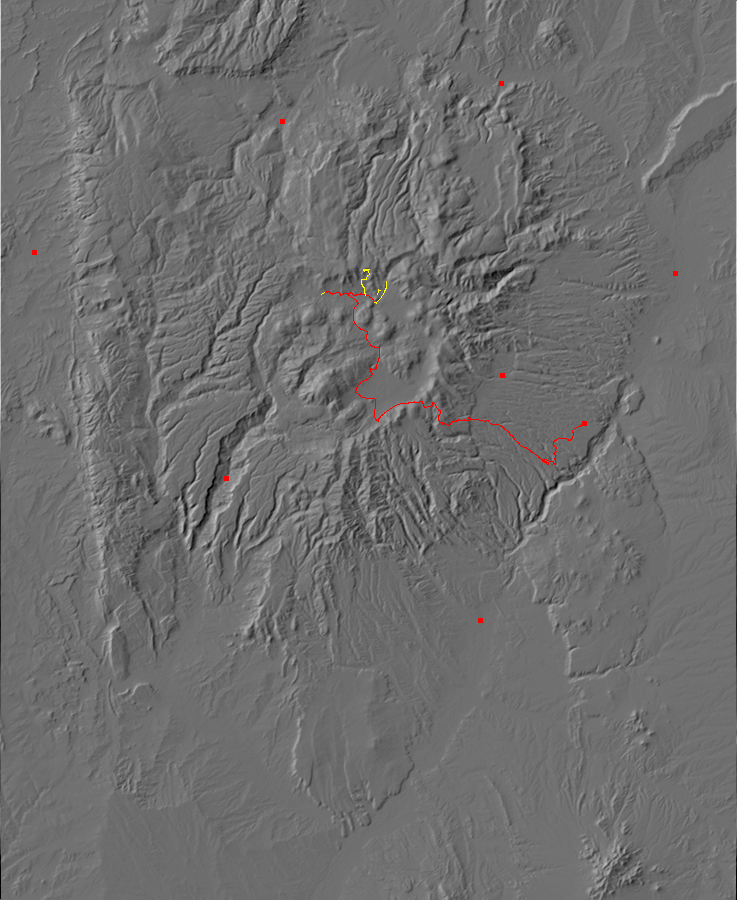

My first objective today is the north caldera rim, via VC 11. This road is closed to motor vehicles, but seems to be well-maintained for use by the Preserve staff, presumably for fixing the north fence, maintaining erosion control, establishing firebreaks if necessary, and so on. My hike would be about three miles each way, but with bushwhacking at the end and a difference of elevation of about 1760 feet. Don’t bring your young children on this one. Here’s the start of the trail.

The road will curve to the right (east) and bring me just beneath a bare part of the rim, ideal for photography.

Bruce Rabe and I walked the first few hundred yards of this road a few summers back. There are outcrops that have been heavily hydrothermally altered by hot, acidic fluids that rose from the Bearhead Batholith beneath. In a few places the Bearhead Rhyolite itself is exposed.

Or, at least, I think this is Bearhead Rhyolite. It’s been heavily altered, which (among other things) has left the rock soaked in orange iron oxides and sulfates. There is also Santa Fe Group in this area, interbedded with the rhyolite, and it can be hard to tell even rocks with very different origins apart once they’ve been boiled in acid.

The road begins to steadily climb.

I tried to be careful to pace myself. As a diabetic, I’m at unusual risk for heart trouble, though I essentially pass a stress test every couple of weeks this time of year. On the evidence, my heart is in good shape. My feet are another matter …

Wildflowers.

Antennaria rosea, perhaps. Small leaf pussytoes, a composite.

The road begins climbing the east side of a drainage.

and comes out onto a subalpine meadow.

Ahead a critter saw me coming and waddled as fast as he could down the road away from me, with one worried backwards glance. This was a hasty shot:

Yeah. Porcupine. The second-largest rodent of North America. I wasn’t anxious for us to meet, either.

Although I note we’re cousins. Rodents and rabbits are the closest relatives of primates among the mammals. Well, you can’t choose your relatives.

The bare north rim comes into view through the trees.

But then the road began to turn east, away from the bare rim. I was tempted to cut across country.

I decided to stick with the road.

I paused and considered. The road turns left up ahead; follow it and have a long but gentle hike along the crest to the ideal photography spot at the right, or bushwhack straight up the hill? There was a flow exposed halfway up; well then.

But first, more wildflowers.

Some kind of daisy. I couldn’t find anything precisely like it online.

I started up the rim, which turned out to be rather steep, but mostly covered with tufts of grass that gave reasonable footing. The spot I chose seemed to have two flows cropping out. The lower flow:

From the map, this should be andesite of the La Grulla Plateau, though I couldn’t be sure of that at the time. I noted it was full of plagioclase feldspar crystals and some dark mafic mineral; I guessed hornblende but the map for the area suggests pyroxene.

Sure looks different, doesn’t it? But it may just be a matter of weathering. This is also mapped as La Grulla andesite.

I worked my way slantwise across the ridge, and soon the objective was in sight.

I climbed the final distance, in a rather fierce wind, and found the perfect spot for the panorama. I ate my orange, then set up and carefully leveled my tripod. And:

My first attempt at a panorama from near this spot, several years back, was pretty unimpressive. Here’s my second attempt, after I had gotten better at it, but the weather was very uncooperative. Both earlier attempts were taken from a point further east where the very shoulder I stood on today got in the way of the view west.

This older one’s really not bad, considering. The weather stank, but it was fall with the lovely leaves, and you do get a slightly better view into the Toledo Embayment at left. Still, I think the new one is a lot better choice for the book. The old one is more an art picture.

I wanted to be really really sure that, with all that climbing, I had got a good panorama. So I took two more with increasingly deep telephoto. The middle resolution came out like

and the high resolution like

As with almost all the images at this site, you can click on the image for a full-resolution version. Which may take some time to download for these large panoramas.

The highest resolution version is wonderfully detailed,with that beautiful deep zoom the new camera allows, but I missed Polvadera Peak at far left and the image seems just a bit cramped. I think the middle one will be the one for the book.

So what are we seeing? Polvadera Peak is at extreme left in the first two of today’s panoramas. Then comes the cluster of domes filling the Toledo Embayment. This is a kind of divot taken out of the 3 to 5 million year old Tschicoma Highlands. The domes that fill it are all between 1.62 and 1.22 million years old, meaning they formed after the Toledo eruption but before the Valles eruption. It was once thought that the Toledo Embayment was the caldera from the Toledo eruption, but it isn’t big enough to account for the volume of rock in the Otowi Member of the Bandelier Tuff that was produced by that eruption, and it’s pretty off-center of the outflow sheets of Otowi Member. It’s now thought to be a kind of extension of the Toledo caldera to the northeast along deeply faulted rocks, with the main part of the Toledo caldera almost coincident with the Valles caldera.

The large valle near center is Valle Toledo. Beyond it and to the left is the east rim of the caldera, with the back side of Pajarito Mountain visible. (You can even make out the radio antenna on top in the highest resolution panorama.) To its right on the skyline, almost directly across Valle Toledo, is Cerro Grande. In front of Cerro Grande and just to its right is Cerro Medio, the oldest of the ring fracture domes. Then comes Cerros del Abrigo and, across a narrow north-south valle, Cerro Santa Rosa. There is a kind of spur from the north rim reaching almost to Cerro Santa Rosa, the lower part of which is Cerro Trasquilar.

We’re now looking at the large valle right of center, which is Valle San Antonio. Behind it is Redondo Peak, which is a resurgent dome, formed shortly after the Valles eruption when fresh magma entered the magma chamber beneath the caldera and pushed up the center of the caldera floor. The Valles caldera was the first resurgent caldera recognized by geologists, and so is the “type specimen” of this kind of caldera.

Strung out along the ring fracture, right of Redondo Peak and south of Valle San Antonio, are Cerro San Luis, Cerro Seco, and San Antonio Mountain. Then comes Cerro de la Garita, the heavily forested high point on the north caldera rim.

The rock at my photography site is mapped as biotite-hornblended dacite of the La Grulla Plateau, and I believe it:

Definitely not the same rock as the earlier two flows. It’s not a matter of color, which is not very diagnostic; it’s that there are fewer and smaller phenocrysts of plagioclase feldspar and some obvious flakes of biotite mica. And the texture is very different; more fine grained and massive.

It was just before noon, and if I got back down off the mountain fast enough, I would still have a high sun for good panoramas at some other locations. I debated the longer but easier hike along the ridge to where it met the road, apologized to my knees, and headed more or less straight down.

No, really:

The picture doesn’t do it justice. That’s a dauntingly steep slope down to the road. But it’s covered with tufts of grass, giving good footing, so down I went.

On the way, I noticed a pond. Could not resist:

Alas, while I saw something splash as I approached, I did not actually see any fish or amphibians in this small, probably artificial, erosion control pond. Just water bugs.

At least three different species.

Elk come this high.

Yes, I was tempted. But, no, it’s still up there.

I got back to my car by about 1:00 and headed to Valle Toledo, to redo a panorama with the earlier camera taken on a rather cloudy day. Alas, they have closed the last leg of the road, before it actually enters the valle:

The road originally was open as far as this point. Well, shucks, and other comments. I ended up climbing the low hill at center to get a clear panorama; the hill turns out not to be that low and its true crest is some distance beyond the visible crest here. At least there were wildflowers.

Dunno. Some kind of buttercup?

A hardy survivor on the slope of the hill. Almost looks like a Mugo pine, but I think it’s more likely to be a fir of some kind. The hill, incidentally, is an old river terrace from when San Antonio Creek had not yet cut down to its present level.

Badger burrow?

That, or a humongous prairie dog.

The panorama:

At left is Cerro Trasquilar to the west. Then come the domes of the Toledo Embayment, with Indian Point at left, Turkey Ridge at center, and the westernmost dome of Cerros de Posos standing out at right. This is thought to be a ring dome of the Toledo event. You can see the east rim of the caldera just right of center, then comes Cerros del Abrigo, the main mass of Cerro Santa Rosa, and the northern knob of Cerro Santa Rosa at far right.

The sun was still high overhead, perfect panorama weather. I decided to detour to Warm Springs Dome and redo that panorama, another one somewhat spoiled by clouds on my earlier attempt.

I found the place had been occupied by Texas. Or, at least, there were a large number of cars with Texas plates parked there, and swarms of people on the dome. Meh. I grabbed tripod and headed up to the top of the dome, pausing for more wildflowers:

Looks like the last set, except those seemed to have toothed leaves and this one has smooth leaves. Still don’t know the species, although I still think it looks like a buttercup.

I found that the Texans were all college aged and most did not have a Texas accent. They were hydrology students out on a summer field camp. When they saw I had a tripod, they got very excited:

“Hey, you’re a photographer!”

“… well, I have a tripod …”

I got recruited to take their group pictures for them, which was not after all so hard and didn’t require any real photographer skill. Which is as well, since I pressed the “info” button instead of the shutter button by mistake the first time. (This was a very nice camera.)

Hydrologists aren’t geologists, but they’re cousins, and when the kids found out I was an amateur geologist of sorts, they asked a little about the local geology. I explained that the Warm Springs Dome is about 1.25 million years old, just a little older than the Valles eruption; was thought to have erupted through the Toledo ring fracture; and was probably a kind of precursor to the Valles eruption. I also mentioned that the pyroclastic beds on the north side of the dome probably came from Cerro Seco to the south. The kids wondered why the rhyolite seemed to be bedded almost vertically on the south side of the dome; I explained the concept of an endogenous dome, whose outer layers tend to be layered parallel to the surface, which would have been close to vertical here. The kids also wondered why the dome wasn’t buried in Bandelier Tuff, which is a good question.

I could answer questions about geology from interested college kids all day.

But I had a panorama to take:

Here’s part of my earlier attempt.

The earlier pan does not include the sector to the south. Yeah, I like the new one better.

At left (in the new pan) is Cerro Seco, a ring dome some 800,000 years old. Then you are looking directly west down the moat, to where the caldera rim starts to curve around to the north. This is one of the lowest points on the rim. At right of center is the north rim directly north of the Warm Springs dome, with Cerro de la Garito to the right. Then you’re looking directly east down the moat again, towards Cerro Trasquilar and the Toledo Embayment beyond. Then come more ring domes, in rank, beginning with Cerro Santa Rosa in the furthest distance and then Cerro San Luis.

I headed back to Valle Toledo, meaning to hike up Rito de los Indios along the northwest rim of the Toledo Embayment. I paused first for lunch: diabetic shake, cheese stick, granola bar, and fiber bar, yum. Washed down with a pint of bottled water. Then I headed out. I was particularly interested in beds of the Santa Fe Group, from before there was even a Jemez volcanic field, exposed at the base of the rim. This would prove frustrating.

Cerro Toledo rhyolite off Cerro Trasquilar dome:

Hullo, what’s this?

See, this is the problem with hydrothermally altered rock. This could be a Santa Fe group conglomerate bed. Or it could be a Paliza Canyon formation volcaniclastic. It’s hard to be sure once it’s been cooked in acid.

And this was about the best candidate for Santa Fe Group I found this entire hike.

I came to the foot of a knoll that I thought was mapped as Santa Fe Group. Turns out I had greatly overestimated how far I had walked.

That’s not Santa Fe Group. That’s just plain dirt.

But there was something more interesting just around the corner.

Lake beds, probably from when San Antonio Mountain erupted, half a million years ago, and dammed San Antonio Creek and created a lake in the caldera.

Silt, clay, and gravel layers. Not tightly cemented, like the earliest Valles lake beds, but containing no pumice, unlike lake beds of the El Cajete lake that formed much more recently. And there’s a road junction just to the east; check the map; ah! I know exactly where I am now.

This was the last decent navigation point I would have this hike. It was guesswork from here on out.

Further up the road I expected a Bearhead Rhyolite dike intruding Paliza Canyon Formation. Both are precaldera formations, exposed here in the caldera rim. Paliza Canyon Formation is mostly andesites around 8 million years old, and they form the lower part of the canyon rim. The Bearhead Rhyolite intrudes older rocks from north of here to well beyond the south rim of the caldera, mostly along a fairly narrow band coinciding with the east side of the caldera. (I wonder if that’s significant.) The Bearhead Rhyolite came from an underground magma body, the Bearhead Batholith, that “sweated” great quantities of acid fluids that hydrothermally altered the rock around Bearhead Rhyolite intrusions, particularly in this area.

I think this is Paliza Canyon andesite that has been strongly altered.

Andesite is normally a fairly dark rock, usually with feldspar phenocrysts. Hydrothermal alteration bleaches rock white, except for orange streaks of iron oxides and sulphates. I thought I could make out the “ghosts” of phenocrysts in this outcrop.

I think this is Bearhead Rhyolite.

And I think we’re back to Paliza Canyon andesite here.

Resuming my northward walking, I came to the hill that purportedly had Santa Fe Group on its southern slopes. There were no obvious exposures of bedrock at all. Shucks.

Further north, and some rocks that looked a bit different from anything so far.

Judging from the map, with the camera’s GPS coordinates for this photograph, this is probably Paliza Canyon dacite.

Further down the road, and lookie here:

A recent debris flow. Probably from watershed denuded by the Las Conchas fire, which swept through the mountains to the east. Too small and recent to appear on the map.

Another outcrop to the left. This is decent recognizable Paliza Canyon biotite dacite.

There’s been some hydrothermal alteration, slightly bleaching the rock and leaving some orange deposits, but not nearly as bad as further south. You can still easily make out the feldspar phenocrysts.

I pressed ahead, seeing what looked like an exposure of the Indian Point dome:

This time, my navigation was good. and that’s almost certainly what this is:

This certainly looks like rhyolite, with flow bands and such. So this is rhyolite of the Indian Point flow, 1.46 million years old, washed down off the dome.

One last longing glance ahead

and I turned around. Man, my feet were killing me; eight miles walking so far today, some over very difficult terrain.

Wildflowers.

Dunno; something in the carnation family?

I still wanted to find some Santa Fe Group beds, so I ignored my aching feet and headed into the hills west of the road. I thought this might be a hill marked as Santa Fe Group:

but my navigation was off again and it turned out to be Paliza Canyon Formation intruded by Bearhead Rhyolite. At least there were wildflowers.

Even I can recognize an iris at a glance.

I headed further northwest, towards what the map showed as a large hill of Santa Fe Group, but this

turned out to be a Paliza Canyon andesite flow just below the actual Santa Fe beds. Had I gone a couple hundred yards further, I would have been at those beds; but then there’s no guarantee I would have found a decent outcropping.

I headed more or less straight at Cerro Trasquilar, since my map showed Santa Fe beds just north of the dome. This area was another old river terrace, crossed by a deep gully.

This exposes the very gravelly surface of the terrace deposit. It’s actually pretty typical for the top of river terraces to be covered with coarse gravel.

I worked my way around the barbed wire, after thinking long and hard about just following the fence down to the road and getting off my sore feet sooner. Up ahead was a knoll that looked very much like it should be underlain by Santa Fe Group, judging from the map.

But, you know? I was just about spent, and I didn’t see anything on the knoll that looked like an outcrop. I decided I was done, followed an old logging road back onto the main road, and got back to my car. Chugged down another pint of water; my throat was very dry and sore. I seriously wonder if the diabetes has destroyed my sense of thirst; I wasn’t particularly conscious of being thirsty on the trail, even though I was apparently flirting with serious dehydration. Chugged down a diabetic snack bar.

I was so tired that when I got to State Road 4 south of Cerro Grande, and saw through the trees that the lighting was just about perfect for upper Frijoles Canyon, I could not bring myself to pull over, climb up the hill, and take the shot. Some other day.

Took Saturday to do yard chores and help a friend move. Monday I plan to just rest up after the hiking and yard work. No adventure next weekend; I’ll be preparing to drive to Logan, Utah, for my niece’s wedding. However, I plan to look at some geology on Monday as I drive through the Four Corners area.

Ah. Good. Jealous. But I wouldn’t have walked that far, just sent Indian Boy to bring back samples.

Indian Boy would probably have found the outcrops I couldn’t, too.

Pingback: And now for something completely different | Wanderlusting the Jemez