Kent and Bruce Have Yet Another Excellent Adventure, Days 6 and 7

Day 5 may be found here.

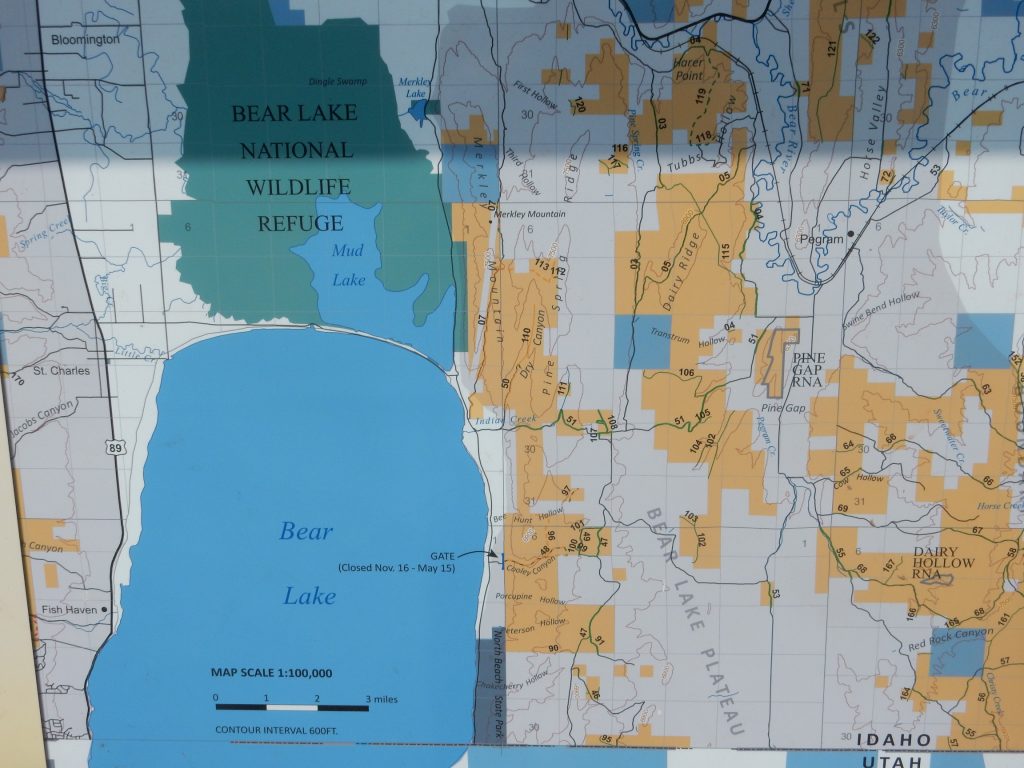

Today is Bear Lake Day. My parents grew up in the Bear Lake Valley and so it’s traditional, when possible, to spend a day at the lake during our reunion.

The low tire light comes on in my car when I start the engine. Crep. I drive down into Logan after finding that the tire still has considerable pressure in it, get some cash from an ATM to pay for my opera tickets, then refill the tire. I’ll have to keep a close eye on it and see if there’s a real problem.

Then back through Logan Canyon to Bear Lake. I am watching for formations, and first soon comes up.

This is the Ordovician Garden City Formation, which is mostly marine limestone. As I’ve mentioned in previous posts, Utah was covered by a shallow sea in the early Paleozoic, with the continental shelf located somewhere in what is now Nevada. This was an ideal environment for depositing limestone, often rich in fossils. The beds are very thick and continue in the cliffs to the northeast, which, alas, are practically into the sun:

I drive past two thinner formations, the Swan Peak Quartzite and Fish Haven Dolomite, without spotting them, but then the next thicker formation towers over the road.

Again, rather too much into the sun, but this is the Silurian Laketown Dolomite. Fortunately, I get a photo over my shoulder with better lighting.

This formation is described as cliff-forming, fined-grained, and sugary-textured. The shallow sea continued to lap over Utah at this time.

Next to catch my eye

is the Devonian Hyrum Dolomite. It contains a few beds of limestone and sandstone but is mostly massive dolostone. I missed the thinner formation between this and the Laketown Dolomite, the Water Canyon Formation, which is more shale and so more easily eroded.

This one I know at once. (The others I will identify with certainty only after getting home and plotting coordinates on the map).

The imposing cliffs are the Mississippian Lodgepole Limestone, which my guide describes as fossil-bearing. It is prominent in the middle canyon and is known local as the Chinese Wall, from a not-unreasonable fancied resemblance to the Great Wall of China. The formations beneath, the Leatham Formation and Beirdneau Formations, are largely mudstone and so form a slope between the more durable Hyrum Dolomite and Lodgepole Limestone that is poorly exposed as seen from the road.

Here is more Hyrum Dolomite at road level.

I think I got out and examined the beds here, but could find no fossils.

The Hyrum Dolomite continues along the canyon for for some distance.

To the southeast from this point, a nice cliff exposure of higher formations.

The lower cliffs are Hyrum Dolomite. Above is a slope of shale and occasional limestone beds of the Devonian Beirdneau Formation, which likely was deposited in a delta environment close to shore. Above this, a line of trees completely obscures the Leatham Formation, which straddles the Devonian-Mississippian boundary. Then comes cliffs of Lodgepole Limestone. The peak in the background shows a solid wall of Lodgepole Limestone — the Chinese Wall — above which are Mississippian and Pennsylvanian beds obscured by forest.

is very close to the contact between the Water Canyon Formation and the Laketown Dolomite. The Water Canyon Formation seems to be a tangled mess like this wherever it crops out.

And here

we are back in the Laketown Dolomite.

Incidentally, these formation names — St. Charles, Laketown, Fish Haven — echo through my family history. They’re all the names of small towns on the west shore of Bear Lake.

This formation jumped out at once when I came to it.

This is the Fish Haven Dolomite, which I haven’t seen good exposures of until now. The road log describes it as medium-bedded and bioclastic. I get out for a good look. There are indeed signs of bioturbation in the beds, where living organisms tunneled and crawled and left their burrows behind.

The second one found its way into my car as a yard rock.

This one I’m not too sure of.

I thought these were ripple marks at first, but there are trace fossils that look like this.

The road turns north into a glacial valley.

The distant peak is Beaver Mountain. Across the road are prominent red beds, the Red Banks.

This is Eocene Wasatch Formation, geologically young beds eroded off the young Rocky Mountains. We saw a great thickness of this north of Salt Lake City yesterday morning.

The road curves east again and passes an outcrop

near a fault trace and thus at the intersection of three different formations. The one that fits the description best is the Cambrian Nounan Dolomite.

These impressive beds

are of the Cambrian Blacksmith Dolomite.

Almost directly south of here is the Peter Sinks Solution Collapse Basin. This is a bowl-shaped depression in a mountain top formed by groundwater dissolving out the limestone beds beneath. Cold air accumulates here in the winter to produce one of the coldest spots in the contiguous United States, with a record-low temperature of -69.3F. It rarely goes four days without freezing temperatures even in summer.

Near the crest of the pass into Bear Lake Valley are some very pretty shale beds.

This is the Cambrian Bloomington Formation.

A small fault trace.

This formation has many such small faults, due to dissolution of limestone beneath, that the geologic map does not attempt to map.

A large concretion in the beds.

From the rest area at the crest, I look across the valley.

The air quality is dreadful. Every other time I’ve been at this crest, the mountains across the lake were clearly visible, as was the valley north of the lake. Today it’s all obscured by wildfire smoke.

I continue down the road and into another spectacular road cut.

This is the lower Cambrian Geertsen Canyon Quartzite. I examine it; there are thin beds of shale but no fossils.

Lots of Cambrian formations along the west side of Bear Lake Valley. I find this somehow fitting. We visited here every year when I was a child, and back then, the roads in the small towns were still gravel roads constructed with Cambrian gravel. These ancient rocks, the oldest with much in the way of visible fossils, seem like a fitting setting for visiting my aged grandparents.

Down into the valley and north along the lake. Our reunion site today is the north shore. I pass another outcropping.

This turns out to be more Geertsen Canyon Quartzite. And the map shows it’s a fault escarpment, though a rather peculiar one; this is a thrust fault and I’m standing on the upthrust side. All I can figure is that the beds I’m standing on were less resistant and so were eroded away.

There is a huge line of cars at the shore.

It’s a maaaaadhouse, and rather than monkey around trying to find a spot close to my family, I park in the first available slot and walk down. Probably better than half a mile.

It’s great to be with the family. But I don’t like sand, so when it’s time to start riding on the Ski-Doos or whatever they’re called, I decide to take a hike.

Back to my car. I try moving it closer. No dice. Back to my original spot (astonishingly, still open). Back to the family again. Then back to my car for a real hike, to the quarry where the stone was obtained for the Paris Tabernacle.

Last time we were here, the tour guide at the Tabernacle told us the stone was quarried from the Nugget Formation eighteen miles to the southeast. It took me a long time to figure out the exact spot, but I had and I wanted to visit.

But first I am distracted by some flatirons north of the lake along the foot of the eastern mountains. Fault escarpment?

Possibly, though I examine the rocks and find no slickensides, the characteristic striations of rock beds rubbing past each other at a fault. I also have only a poor geologic map of this area; my best guess is that this is Phosphoria Formation, a Permian formation mined for phosphite.

Not much evidence of fossils in the cliff.

Some hints of shells and other fossils, but only poorly preserved, in rock fall.

I proceed to Indian Creek Road, the road to the quarry.

The road is on private land at first, and I have no decent map of the first mile or so. This outcrop

appears to be a quartzite, and has no fossils, but I havent’ even a good guess what formation it is. The poor map I have labels it Trtp which would indicate a Triassic formation, but I have no legend to identify it further.

This outcrop likewise, though it looks like it might be cut by a fault.

This hill is described as Traw, so also Triassic, but I don’t know which formation “aw” is.

looks a little like the red sandstone the Paris Tabernacle is build of, but the area is still labeled Triassic. And then I’m onto BLM land.

And here I finally get to something I can put a definite label on.

This looks very much like the sandstone of the Tabernacle, and the map labels it Jn — Jurassic Nugget Formation? Maps of nearby areas for which I do have a legend use Jn for this formation, so there it is.

This is not yet the quarry. But I’m in the right neighborhood.

Further down, the rock changes again.

Extrapolating a bit from my maps, it seems this is Jurassic Twin Creek Limestone. It’s a bit younger than the Nugget Sandstone, consistent with the road cutting through progressively younger beds. It certainly looks like a limestone, though I spend some time looking at the rock here without finding any good fossils. Just some poorly preserved hints of shells.

In places the limestone is coarsely crystalline. This suggests some recrystallization that will have tended to spoil the fossils.

I cross the creek, which has turned north, and there is more Twin Springs Limestone.

I examine this for some time, but still don’t find any clear fossils. However, I acquire a passenger.

The ascending road is back into the Nugget Formation.

Or so I think. This area is mapped as the Gypsum Spring Member of the Twin Springs LImestone, which is described as red-weathering beds of limestone breccia, mudstone and sandstone. Perhaps this is just a large block of Nugget Sandstone from up the hill.

The gate to the first quarry. There are two mapped here.

The quarry beyond.

This quarry appears to have been inactive for some time. My guess is it’s the one from which the stone for the Tabernacle was taken.

I take a side road south; it ends in a big pit that does not look like a quarry. Possibly a large barrow pit. From the rim, I can look back at the quarry.

I am on the Bear Lake Plateau.

To the left is the Thomas Fork Valley, on the Idaho-Wyoming border. To the east, the low Sublette Range, and then rolling hills across a good part of Wyoming.

There is a gated road to the north, where the map shows the second quarry. The gate is closed but not locked or posted. I consider, then park my car and walk past the gate. I am soon at the quarry.

There is a large pile of Nugget Formation boulders and a rock sorter.

The quarry is obviously still active, though it’s shut down now for the weekend. The boulders are large enough for use in dimension stone (stone cut to specific sizes and shapes, such as building stone or tombstones). However, I suspect most of the stone here is being quarried for use as crushed stone.

The main quarry pit:

Since I am an uninvited guest, I am careful to touch nothing and keep my distance.

I’m out of time; I hurry back to my car and head back down the road to the lake.

I am to rendezvous with my family at the Paris Cemetery. I do not get a cell signal until I am out of the canyon; then I find that the rest of the family is actually running more late than I am. So I am the first to arrive at the cemetery. (Which, on reflection, seems like an ill omen.)

I park near the west end.

It’s a beautiful cemetery, resting on a gentle hill above the rural valley where my people come from. I would like to be buried here someday.

No hurry.

My mother and father.

I realize with a start that I am now older than my father was when he died. Mom, of course, is still with us.

We gather for some photographs of the family (which I may post later) and then look at some of our other relatives’ graves. Very near my father is my uncle, one of his sons, and one of my aunts. Both sets of my grandparents are also in the cemetery, along with other, more distant, relations.

My uncle was probably as enthusiastic an amateur geologist as I am. He introduced me to my first geodes. There is a pile of geodes on his gravestone. On impulse, I add a bit of Mancos Shale from the car carrying an Inoceramus fossil.

The cemetery is surrounded by pastures.

My niece Bailey, animal lover that she is, cannot resist bothering the cow.

My father’s childhood home.

I am in a rush to keep up and do not get a picture of my mother’s childhood home.

The gang drive down to Garden City for shakes at LaBeau’s. There is no such thing as a diabetic-friendly shake in Bear Lake Valley, alas, and not that much in the way of main courses. I finally risk a turkey and avocado sub sandwich, because my stomach is screaming for some solid food.

Afterwards we will be scattering, so I say my goodbyes. Then back through Logan Canyon. I cannot resist one geology stop, for a picture of lake deposits just out of the canyon.

These beds cannot be more than about 20,000 years old, which is a few minutes ago in the geologic scale of things. They’re a nice model for vastly older sedimentary beds.

Then down the Wasatch Front to Provo. The smoke is only getting worse, but this I can’t resist.

The thick white layer is our old friend, the Cambrian Tintic Quartzite. Below is the Neoproterozoic Farmington Complex, so we’re looking at the Great Unconformity at the base of the Tintic Quartzite. Above is the Cambrian Maxfield Limestone.

The Great Unconformity is the name given to the boundary between Precambrian and Phanerozoic rocks in the western United States. Almost everywhere in this region, there is a large gap in the geologic record between a time when life was very simple and left very few fossils (the Precambrian) and the time of first fossil-bearing beds, which by definition are assigned to the Phanerozoic (“visible life”) Eon. Here the gap is probably some hundreds of millions of years. In my neck of the woods, it’s over a billion years.

I arrive back at Provo, well ahead of Lori, but she soon catches up, lets me in, and we turn in for the night.

The next morning is Sunday. I go to church with my sister, and then we spend the entire afternoon talking. When I was a goofy young nerd, hooked on Star Trek, impressing people with all the facts I had collected in my head, poor at athletics, and an inviting target for bullying, Lori was one of my chief protectors. Not physically, but emotionally.

We take time in the evening to drive over to my mother’s and visit some more. Mom is 87 and nearly blind, but her mind is still reasonably sharp.

Next: Bruce joins the adventure.