Treasures

This was a weekend for treasures.

Earth Treasures Show

Gary Stradling and I visited the Earth Treasures Show this morning. This is an annual adventure for me, in which I enjoy looking at wonderful minerals specimens and am relatively painlessly separated from a modest number of quatloos.

The event is sponsored by the Los Alamos Geological Society and has been held at the Masonic Temple at Los Alamos every year I’ve attended. The front hallway:

This is normally the site of the geode sale and silent auction. The geodes are uncut; you pick out a likely candidate, pay for it, and the sale price includes having the geode sawed in half on the front steps. Gary got one; I’ll be interested to see how it came out. (We could not linger long enough to watch it be cut.)

The silent auction is of donated mineral specimens. You find one you like, write down a bid, and check back periodically to see if someone else has written a larger bid and decide if you want to top it. Proceeds apparently pay for students to attend a geologic conference. I’ve picked up a decent sample or two this way, but not this year. (There was a promising looking sample of graphic granite, but I missed the chance to bid on it.)

Silent auction items.

The fluorite and galena sample at right caught my eye, but the starting bid was $50, which was already out of my range.

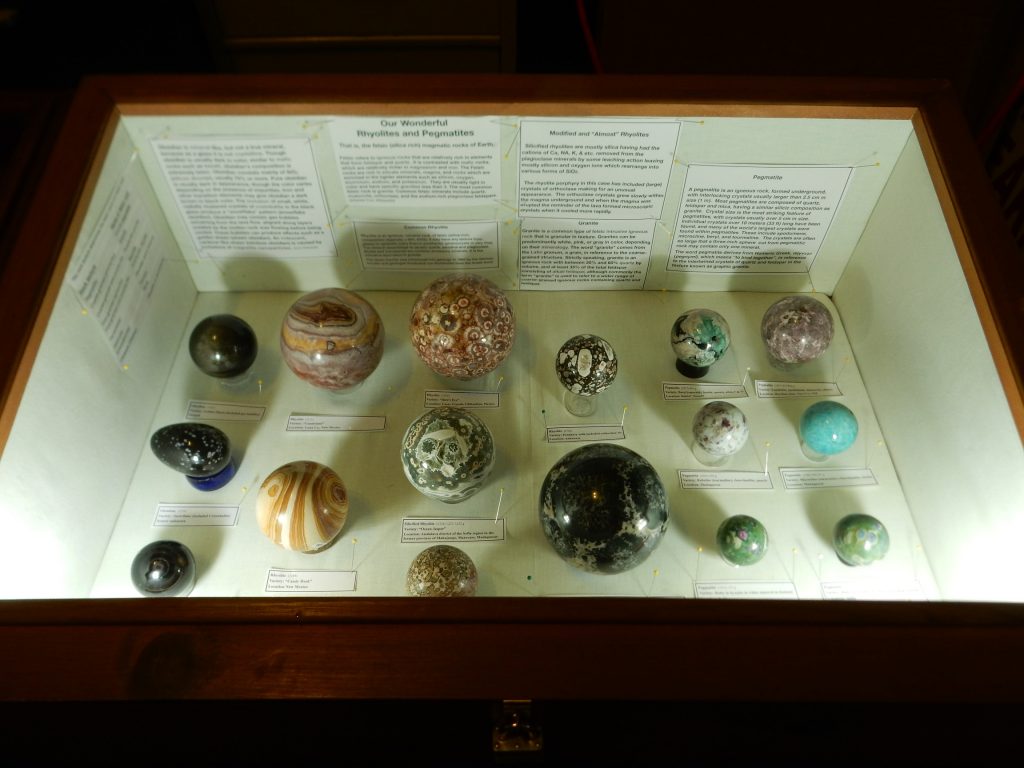

In addition to the items for sale, the Los Alamos Geologic Society puts together some nice displays of items not for sale. One theme this year was rhyolite, a silica-rich volcanic rock.

Polished spheres of various kinds of rhyolite. The left column is various kinds of obsidian, which has the composition of rhyolite but cooled so quickly that it formed a volcanic glass. Looking at the orbicular rhyolite, at top center, seemed to make my ankle hurt; I broke it a year ago trying to reach an outcrop of orbicular granite in the Sandia Mountains. Still, some nice samples here.

Assorted mineral specimens.

These are tantalizing; some are just outside my budget, which is frustrating. And I cannot see the word “fragile” without mentally pronouncing it “fra-GEE-lee”, like Daren McGaven in A Christmas Story. Love that movie.

I was looking for some nicely crystallized sulfur, for the book, and there was a small sample here within my price range. I made a mental note.

View of the main vendor area.

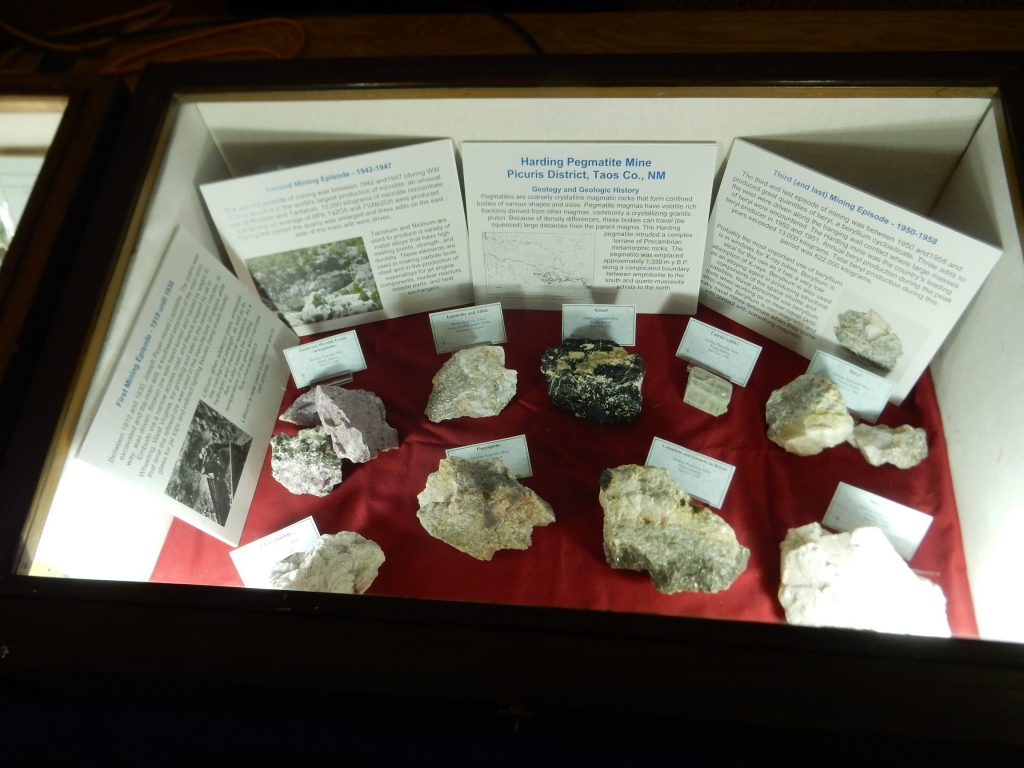

A pegmatite display.

There are some feldspars here typical of pegmatites, and a sample of lepidolite at the upper right. The beryl, at center, caught my attention; I hunted for some at the Harding mine during the Society’s field trip there, but came up empty. I do not know what rubellite, the purple mineral at top, is.

Pegmatites are interesting because some pegmatite outcrops contain rare minerals, including ores of scarce elements like lithium, beryllium, and tantalum. They’re thought to form from the very last part of a big magma body to crystallize, and are rich in incompatible elements.

The twelve most common chemical elements make up 99% or more of common rocks. The other 78 naturally occurring elements are present only in trace quantities. When a body of liquid rock, magma, cools and crystallizes, the minerals that form first are typically minerals of the most common elements, such as feldspar, which is rich in the common elements oxygen, silicon, aluminum, sodium, potassium, and calcium. But the trace elements sometimes sneak their way into the crystals as well. This is particularly true of compatible elements, which have a similar ionic charge and radius to the common elements making up the bulk of the crystal. For example, manganese is a compatible element with ferrous iron, having nearly the same ionic radius and charge; as a result, distinctive manganese minerals are not terribly common even though manganese is the twelvth most common element in the Earth’s crust. It sneaks its way into iron minerals to replace some of the iron, rather than forming distinctive minerals of its own.

The ions of incompatible elements have a combination of charge and radius that is not like any common element, and so they have a tough time sneaking into the common minerals as they crystallize. They tend to remain in the remaining liquid portion of the magma instead, where they can become highly concentrated. This is actually similar to how silicon is purified to make computer chips (which requires extremely pure silicon). In the process of zone refinement, a slug of silicon is repeatedly passed through a heating element, forming a narrow molten zone in the silicon where silicon is slowly melting on one side and crystallizing on the other. The impurities tend to remain in the liquid silicon, and end up concentrated at one end of the slug — which is sawed off, leaving the rest of the slug extremely pure.

In the case of a pegmatite, the last part of the magma to solidify is so enriched with incompatible elements that they form easily mined minerals. We get most of our lithium from underground brine pools (where it is concentrated by a similar process), but the lithium minerals lepidolite and spodumene, found in some pegmatites, are an important additional source. Beryllium mostly comes from beryl found in pegmatites.

So does tantalum, and for a time the most important source of tantalum in the United States was the Harding Mine.

The Harding Mine is located east of Dixon, on the road to Taos, and is mostly tapped out. The mine now belongs to the University of New Mexico, which hosts geologic tours and limited collecting. I’ve been there three times myself, the last with LAGS, and it’s always great fun. Spodume and lepidolite are easy to find; other minerals, like tantalite, apatite, and beryl, require more work, but I’ve got samples of all but beryl.

One of the simplest and most common minerals is quartz, silicon dioxide, but it comes in some spectacular and occasionally rare forms.

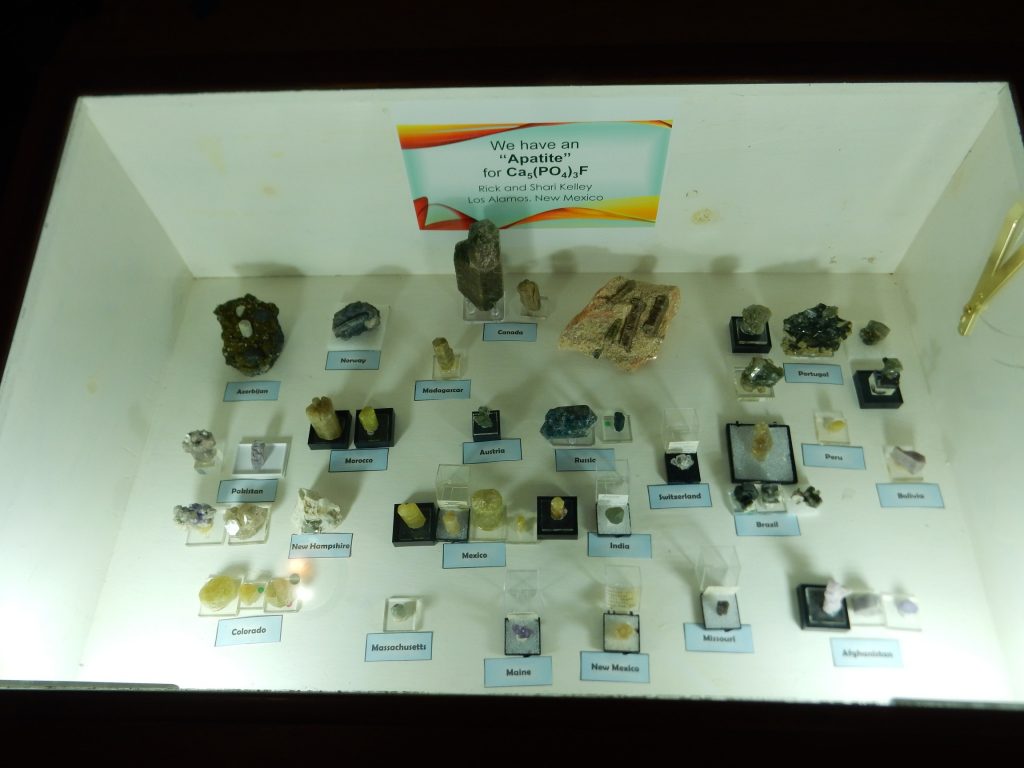

Rick and Shari Kelley are professional geologists and great friends of the LAGS, who apparently have enormous apatites.

Apatite is a form of calcium phosphate incorporating hydroxyl, fluorine, or chlorine. It’s a common pegmatite mineral and is found in other types of rock outcrops as well. It’s not particularly valuable unless it is well crystallized; these samples are well crystallized.

It also fluoresces beautifully under a UV lamp. Rick seems fond of fluorescent minerals and has convinced me to put a decent UV lamp on my Christmas wish list.

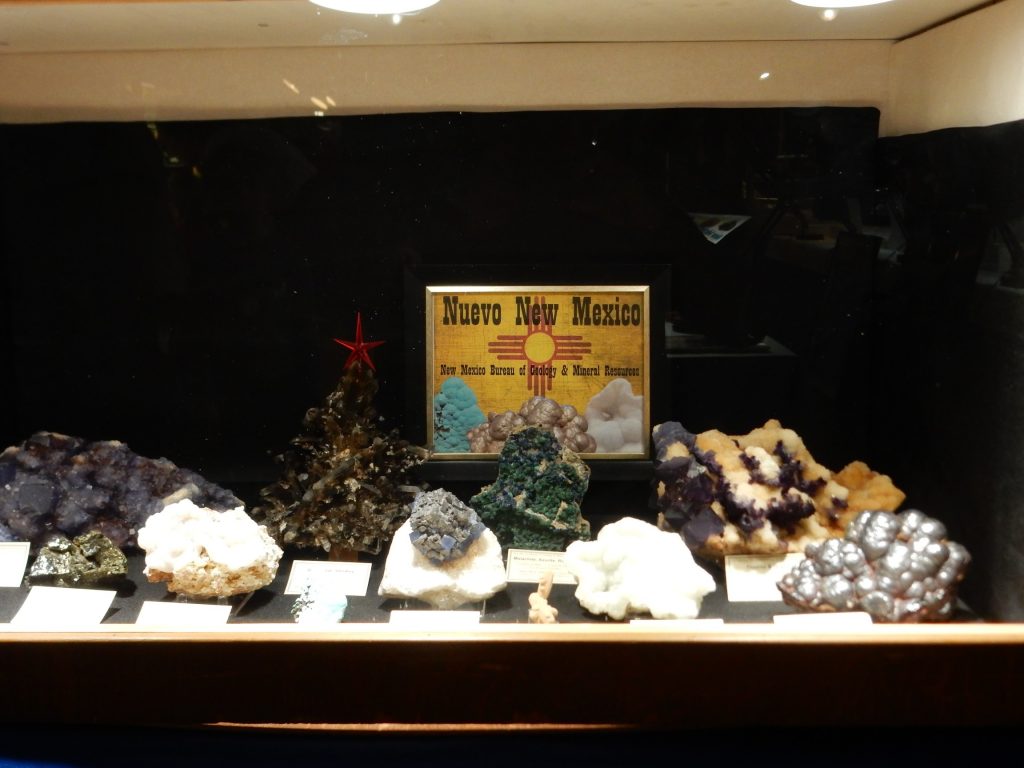

There is traditionally a row of museum-quality pieces at one end of the floor. These are not for sale; the best would be worth thousands if they were:

It probably goes without saying that I have no museum pieces in my collection. The one that comes closest, a slab of schist full of staurolite crystals, might go for a hundred bucks in the right venue. Most of my collection is interesting only because I know where I got the rocks and what their geologic history is.

I snapped a shot of Patrick Rowe, our faithful tour guide on many of our LAGS trips. Alas, although the autofocus on my camera is feeling much better, this particular shot turned out blurry.

Gary was finding all kinds of great stuff, including trinkets for grandkids. I found a beautiful fire opal, but decided not; Cindy loves fire opal, but she would not be happy with me paying that much for one. I settled for a tile of Green River Formation with a fossilized fish (I’ve wanted one for a while and this one was just within my budget) and the aforementioned lump of sulfur crystals.

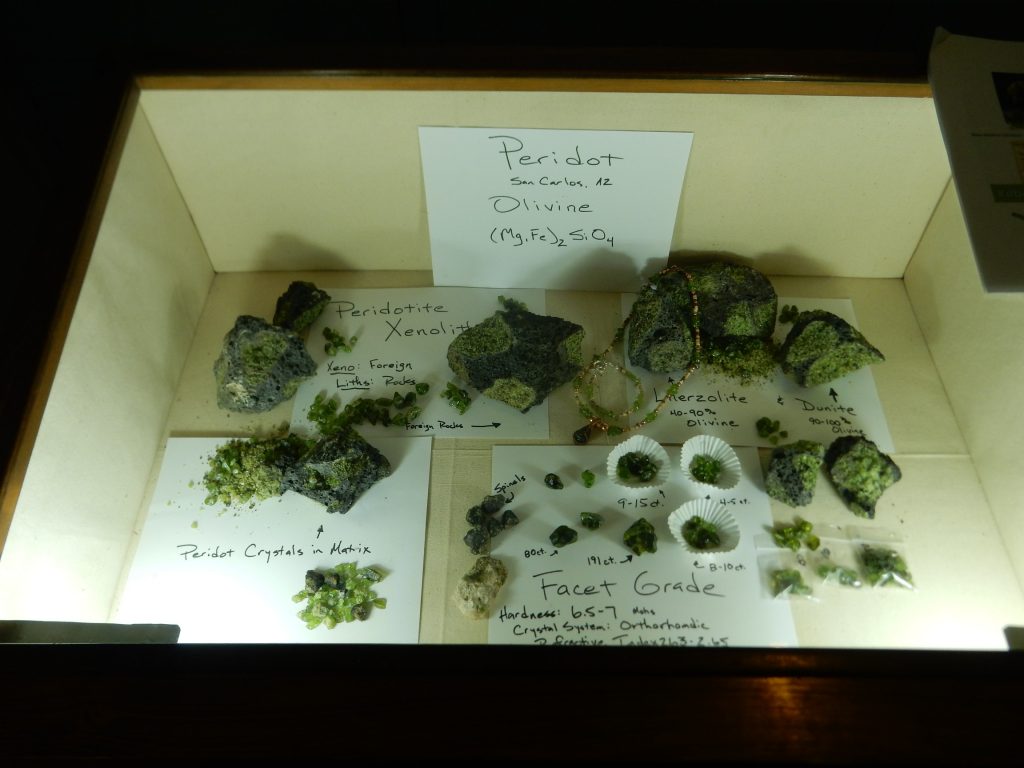

How about a piece of mantle for a mantle piece?

The green stuff is chunks of the Earth’s upper mantle, brought up by the eruption of the basalt in which they’re embedded (xenoliths). The most common mineral in the mantle xenoliths is olivine, magnesium-iron silicate. Alas, not for sale; I’ve priced similar specimens at $200 at previous shows, and I have a very small specimen I purchased at a show in Creede Colorado, last summer. The nearest place on public lands you can find the stuff is Kilbourne Hole in southern New Mexico, which I think I talked Gary into visiting with me sometime later this winter.

Waiting for Gary’ geode to be sawed in half.

We couldn’t linger to watch, because we wanted to visit the

Creche Show

This always takes place the same weekend as the Earth Treasures Show, just down the street at the LDS chapel. Here we see a different kind of treasure.

Nativity scenes in many styles from many countries.

Moosemas:

From Alaska. Some tourist kitsch has a certain charm.

I snacked on cheese blocks, little spicy weiners, and meatballs before heading out. I needed to be home in time for

Thurgood family Christmas party

which Cindy and I hosted this year. We chose to have this at the local pizza parlor, which we more or less invaded and occupied for two hours. (It was a profitable occupation for the parlor.)

Treasured family:

(Not everyone loves the camera.)

The white elephant gift exchange was a riot. I got home feeling like life is good, which is what Saturdays are for, right?