Wanderlusting Cerro Rubio

It’s been a while since I spent some serious time hiking in the Sierra de los Valles, the range of mountains west of Los Alamos that is also the east rim of the Valles caldera. This is not an area to hike during thunderstorm season, but the forecast was for good hiking weather today and I decided to seize the opportunity.

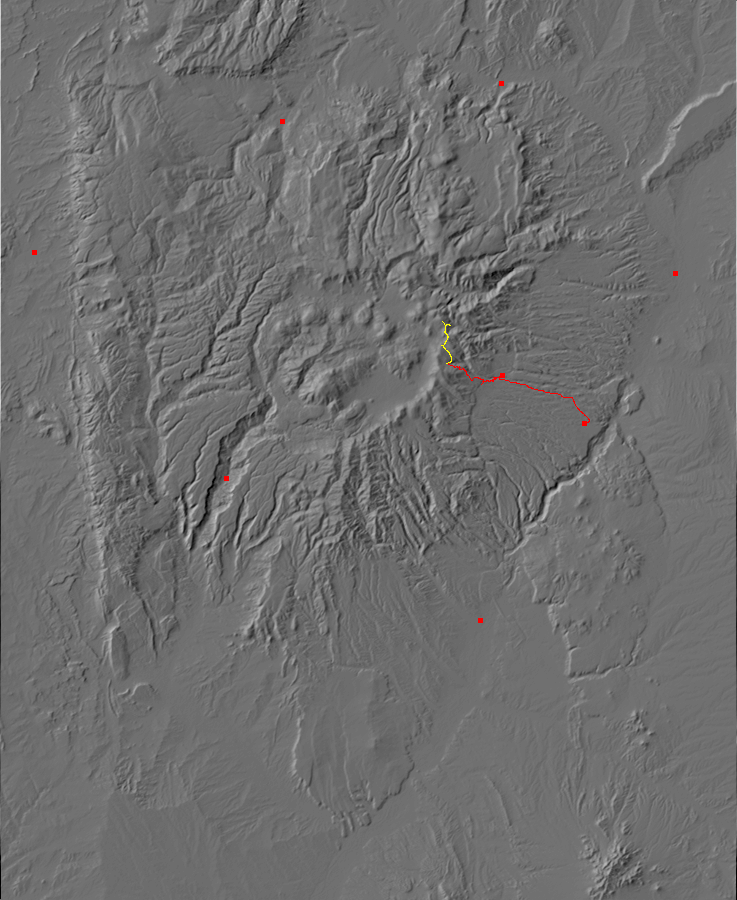

My route would take me from the Pajarito ski basin north to Cerro Rubio (“Blond Hill”). I hoped to see some good views of the caldera from its east rim, of the Los Alamos area to the west, and of the Toledo Embayment. I also hoped to get some samples of the upper Quemazon Canyon dacite and of the Cerro Rubio dacite.

I am up early, eat the usual breakfast (steel-cut oats with ground flax seed, blueberries, and sucralose; high-protein chocolate pancake with sugar-free syrup; homemade kefir with xylitol; bacon and eggs. I’m diabetic.) I turn the fish tank on for the day, clean the dishes, and head to a friend’s house to take care of their dog, (They are out of town as volunteers with a youth activity.) I get about halfway to the ski hill and Cindy calls. I forgot to leave her the house key so she can take the dog out at noon. I mutter some naughty words at myself, drive home, drop off th key, and drive back up to the ski hill.

At the trail head.

The Wandermobile may need to go see a mechanic; something is rattling in the underbody. But the car makes it here okay. I pack up, put on my hiking boots, turn on my SPOT tracker, and head out.

I’m not 100% sure where the trail head is but quickly find it.

The trail leads to Canada Bonita, which is a popular cross-country skiing area. Today it’s hikers and bicyclists.

It’s a good trail.

And my GPS lock is way off. Terrain?

Pajarito Mountain is underlain by the Pajarito Mountain Dacite of the Tschicoma Formation.

Dacite is a volcanic rock that forms when lava fairly rich in silica erupts to the surface. Silica makes a lava viscous, and the lava that forms dacite is about as viscous as Silly Putty. The lava tends to have big white crystals (phenocrysts) of plagioclase feldspar that formed while it was still underground, and these are visible in the dacite. I’ll put up some good pictures in a moment.

Pajarito Mountain was a vent for such lava, which erupted around 3.1 to 2.9 million years ago, based on argon-argon radiometric dating. This method of dating determines the age of a rock by measuring how much trapped argon has built up in the rock from the decay of its content of radioactive potassium.

This vent was part of a period of volcanic activity, from about 7 million to less than 3 million years ago, that erupted mostly dacitic lava all along the Sierra de los Valles and the Tschicoma Highlands to the north,. The rock produced by this pulse of activity is called the Tschicoma Formation. There are some beds of Tschicoma Formation dacite in the west wall of the caldera, showing that the active area must have included what later became the Valles caldera, though these vents are now deeply buried under the caldera floor.

I don’t ski myself, but the ski area is certainly beautiful. A panorama:

(As with most images at this site, you can click to enlarge.)

The trail forks.

I recall seeing this on the map, and I believe they join up again further on. Still, it could be awkward if I’m mistaken. The left trail looks better and I take it.

A view down into the confluence of Canada Bonita and Quemazon Canyon.

Upper Canada Bonita is a relatively gentle valley, but the lower portion descends more steeply to its confluence with Quemazon Canyon. Below the confluence is Los Alamos Canyon.

I promised some photographs of the Pajarito Mountain Dacite. Here’s one:

You can see that it has plagioclase feldspar phenocrysts in a bluish-gray, very fine-grained matrix. This is pretty typical of a dacite, though many of the dacites around Los Alamos have a reddish matrix rather than bluish. Plagioclase feldspar can freely replace calcium and aluminum in its structure with sodium and silicon; in a high-silica lava like dacite, the plagioclase will tend towards the sodium-rich side.

And, as so often happens, I promptly come to a better outcrop.

The size and number of plagioclase phenocrysts varies from location to location.

Wildflowers.

Canada white violet, I believe. I had to look this one up. I have a modest but far from exhaustive knowledge of plants.

Wild strawberry. (I did not have to look this one up.)

There were also numerous dandelions, but I took no pictures. Dandelions are why God invented

Oh, I know. But dandelions are an invasive, exotic species, and I have no sympathy for them.

The trail comes out on the Canada Bonita.

I scout enough to see dacite boulders in the valley floor, then get a panorama.

A lot of south-facing slopes in the Jemez are bare, presumably because they lose snow cover during bright winter days and exposed tree seedlings freeze in the cold night air.

More wildflowers.

These look a lot like the Canada white violet, but not white. A slightly different variety?

I come to a fence.

It’s the boundary of the Valles preserve. The fence is rather porous and there may be a great view of the caldera from the crest beyond. I decide to save it for the return leg.

I find myself sharing the trail with bikers. There will be another group on the return leg. I meet two groups of hikers, one quite large. Otherwise it’s a quiet trail.

Looking back down the valley.

The trail turns north, crossing a ridge of Rendija Canyon Member dacite. This is slightly different from Pajarito Mountain Dacite, being somewhat older (around 3.5 million years in this area) but I don’t notice a difference and don’t realize I’m on a different flow. The view opens out slightly to the north.

The mountain at dead center (first peak left of the trail) with the meadow on its face is Tschicoma Peak, the highest point in the Jemez and the namesake of the Tschicoma Formation. To its left and closer to us (and, unfortunately, right behind a big clump of dead trees) is my objective today, Cerro Rubio. At right (directly over the trail) is Caballo Mountain. A lot of interesting terrain below the peaks is obscured by the forest.

I continue north, and cross some kind of boundary. Looking back:

Apparently I’m in the Pipeline Road corridor, which for obvious reasons cannot be shut off to motor vehicle traffic. And my GPS absolutely refuses to lock in this area. And there is a loud buzzing sound; perhaps a beehive in a nearby tree?

I come to a clearing where my GPS finally locks.

The western half of Pipeline Road.

The actual pipeline heads straight west from the intersection ahead. However, “straight west” is also “straight down a cliff” and the service road has to wind its way down a slightly different path.

And, yeah: I’m not sure what all the reasons were for running the gas pipeline to Los Alamos straight across the Valles Calder, with its rough terrain, but I suspect local land politics.

I decide to explore Pipeline Road just a little.

I’m hoping to find a clear view to the caldera to the west, but the road turns out to be heavily forested. Which is good; I’m glad to see that the two most recent massive forest fires in this area spared as much forest as they did.

I continue on across the Bandelier Tuff plateau.

I’ve mentioned the Bandelier Tuff a couple of times now. The Bandelier Tuff records a series of at least three caldera eruptions, where a body of very high-silica magma beneath the Jemez broke through to the surface. Such magma tends to be gas-rich but extraordinarily viscous, roughly like roofing tar. When it hits air, it tends to disintegrate into a red-hot mixture of gas and tiny shards of volcanic gas. This mixture is heavier than air and can flow across the ground for files as a pyroclastic flow, destroying everything in its path. The vast amount of magma erupting from the magma chamber forms an outflow sheet as the pyroclastic flows, moving out in all directions, settle to the ground and cool to form a rock called ignimbrite or (less formally) tuff. The emptied magma chamber collapses to produce a caldera.

The first eruption(s) were relatively small, producing the Culebra Member of the Bandelier Tuff about 1.85 million years ago. This is found mostly in the southwest wall of the caldera and along San Diego Canyon. The caldera produced by this eruption was destroyed by the later, larger eruptions, but may have lain in the western part of the Valles caldera, based on drilling. More recently, it has been suggested that the Toledo Embayment, a divot taken out of the older rock northwest of the Valles caldera and filled with younger lava domes, might have been the caldera that produced the Culebra Member, but that’s not widely accepted. Cerro Rubio sits on the southeast margin of the Embayment and was thought to be a young dome until radiometric dating showed it was part of the older Tschicoma Formation.

The next eruption occurred 1.62 million years ago and was ginormous, producing a caldera perhaps 10 miles across and covering the surrounding countryside with its outflow sheet. This is the Otowi Member of the Bandelier Tuff. The magma chamber refilled and broke out again 1.25 million years ago to form the Tsherige Member of the Bandelier Tuff, which underlies the Pajarito Plateau east of the mountains. It also filled most of the canyons in the mountains themselves, and left a bench on the western face of the Sierra de los Valles that I am now hiking on.

The eastern half of Pipeline Road.

Where the pipeline itself goes over a cliff.

I’ve alluded to it already, but there is a certain weirdness about how Los Alamos gets its natural gas supply. The main gas pipeline comes in from Cuba, and its path is still discernible on satellite as a zigzag path through the terrain to the east, starting here. In some places, the pipeline lies very close to a road still in use, while in other places the road is nearby but still some distance from the pipeline trace, as the pipeline follows as straight a path as possible over difficult terrain while the road takes a more manageable path. The pipeline passes through the Sierra Nacimiento via Senorita Canyon, then through quite wild country south of Jarosa and past Twin Cabins, and then into the caldera, where its trace becomes easily visible. Here the occasional jogs of Pipeline Road away from the actual pipeline are obvious. There is no way out the east side of the caldera except straight up a cliff, and Pipeline Road of necessity takes a big jog to the south to switch up the cliff. But Google Maps erroneously (and quite dangerously) shows the actual pipeline trace as Pipeline Road, so the cairns blocking off the path over the cliff are probably a good idea.

The remaining path into Los Alamos is a windy one, which must have been a nightmare for the pipe layers. There would have been no choice but to put frequent turns into the pipeline, which are very expensive.

Pipeline Road itself is theoretically drivable — it has to be, as a maintenance road for a major natural gas pipeline — but is normally closed to unofficial vehicular traffic. Hiking it is perfectly legal but it’s a long, long hike from the Los Alamos side. Hiking to it from the ski basin, as I’m doing here, is much easier.

As I’ve mentioned, the one disappointment on this hike is that the forest cover obscures otherwise promising viewpoints. I get only a narrow glimpse of the caldera from here.

The mountain just right of center is Cerros del Abrigo, “Hills of the Thief”, one of the ring fracture domes of the Valles eruption. The Valles caldera dropped a plug of rock roughly ten miles across into the underlying magma chamber, producing a ring-shaped fracture that remained a zone of weakness. Subsequent smaller batches of magma made it to the surface through this fracture, producing domes that line the ring like beads on a wire. Cerros del Abrigo was the second ring dome to erupt, around 970,000 years ago or a little over a quarter of a million years after the main Valles event. Ring fracture eruptions have occurred sporadically ever since, the most recent at Banco Bonito a touch over 70,000 years ago.

The meadow in front of Cerros del Abrigo is Valle de los Posos, “Muddy Valley”. It’s part of the “moat”, the area between the ring fracture (and ring fracture domes) and the topographic rim of the caldera. The rim left by the ring fracture itself was highly unstable and quickly collapsed, moving the topographic rim a considerable distance outward. We’re standing on the lip of that topographic rim now, underlain by Bandelier Tuff erupted by the caldera eruption, which obviously had time to solidify before the rim collapsed out this far.

Yeah, it’s Pipeline Road all right. There’s the pipeline warning sign, and the start of Guaje Trail to the left heading north.

As I hike north, I start looking for a change in the bedrock. Here it’s still Bandelier Tuff.

You can tell because the tuff is relatively light, is not actually very tough, and has glistening crystals of quartz and alkali feldspar. I’m looking for an outcrop of dacite the trail should cross in this area. Perhaps here?

This is one of the outcrops I want to sample, but I don’t want to carry the rock further than I have to. I decide to explore and sample on the return leg, and I’ll discuss the outcrop then.

I see a side trail to the rim, and this will turn out to be one of the better views of the day (though still not perfect.)

At left is the unnamed peak north of Pajarito Mountain that forms the northwest rim of the ski basin. The southern rim of the caldera just peeks over its right shoulder. The mountain partially obscured by the tree is Cerro del Medio, the first of the ring fracture domes (erupted almost immediately after the Valles caldera eruption), and the mountain framed between the trees at right is Cerros del Abrigo

I come into a badly burned area and my objective is ahead.

And as I write this, I’m kicking myself: There’s a chance that, if I had hiked west to the rim here, I might have gotten a fairly clear view into the caldera. It didn’t even occur to me, perhaps because at this point I expected a good view from atop Cerro Rubio, and on the way back I was just too tired to think of it. But there’s no guarantee; it looks like there might be standing burned trees clear to the rim.

I appreciate the timely work of volunteers keeping the trail clear.

During the entire hike, I encountered only one tree across the trail that had not been cleared yet. Kudos to our local volunteer trail-maintainers.

Wildflowers.

Wild iris, of course. Iris missouriensis. As I said, I’m not terribly knowledgeable about botany, but I know an iris when I see one.

I arrive at the foot of Cerro Rubio. It’s clear it will be a nasty ascent; the ground is covered with a maze of fallen trees and patches of shrubbery. I continue on the trail as it turns east, both in hopes of seeing a clearer path to the top and because the map suggests there is a spectacular lookout ahead.

The trail follows a knife edge.

This is eroded out of the Bandelier Tuff, which is a perfect rock for erosion into steep cliffs, knife edges, and tent rock.

There are amazing views to north and south, though with just enough standing dead trees in the way to be a problem. Ahead, there is a cairn; I fail to spot a second one that indicates the trail stitching back and down the north side of the knife edge. Beyond are some potentially clear viewpoints, if I can get to them without killing myself. And I already have a pretty clear view to the south.

The mountain at center has no official name, but is known locally as either Rendija Mountain or Quemazon Mountain; it is located at the head of Quemazon Canyon to its south, while Rendija Canyon organizes itself from a fan of small arroyos some distance to its east. The mountain is underlain by Rendija Canyon Member, which is between 5.6 and 3.5 million years old. (Probably closer to the younger date under the peak.) The valley is an unnamed spur of Guaje Canyon, with the knife edge at left obscuring the confluence. This location is, unsurprisingly, known locally as Guaje Overlook.

I debate whether to try to get out further on the knife edge. I’m also puzzled that I know there must be a trail down, but I can’t imagine where it could be. (I missed seeing the switchback.) I am about to turn back when I see a large group of hikers ascending the knife edge from the north. I don’t know why, but this encourages me, and I slither my way further out on the knife edge for what is probably my best panorama of the day.

(Click to embiggen.)

Quemazon Mountain at right again, and looking down Guaje Mountain past the knife edge. At left is Caballo Mountain, underlain by the Caballo Mountain Member of the Tschicoma Formation (3.06 million years old.) That’s another rock type I may not get a sample of for a while; the north half of the mountain,and most of the exposures to its northeast, are on tribal land. There are outcrops around Guaje Reservoir, and those are my best bet.

The bench left of center, and the tall cliffs on the east side of uppermost Guaje Canyon at far left, are Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff. The spectacular tent rocks in the canyon are of potentially great geological interest:

They intrude the 4.21 million year old Tshicoma Formation beds in the area, and identical rock further west intrudes 1.33 million year old Toledo Embayment rock, but seem to underlie the Tsherige Member, in spite of having a measured radiometric age a hair younger than the Tsherige Member. Furthermore, indications are that both outcrops appear to plug the vents through which they erupted. These could shed light either on the nature of the Toledo Embayment or on the earliest stages of the Valles eruption. However, while the east plug is on Forest Service land, there does not appear to be a trail off the main Guaje Trail that goes up the canyon, and the area is a maze of fallen trees. I can put it on my bucket list, but there’s little chance I could make the hike up and back in a single day, and I’m getting too old to backpack in with a tent, sleeping bag, and provisions for an overnight stay. A mule would not do well crossing all the dead trees, even if I could rent one. I suppose I could hire some porters …

The group I saw below are now above me on the knife edge. I slither my way back, and find a group of mostly teenagers with a couple of adult women. They point out where the trail switches back (that I had missed.) I have no particular desire to descend further; the trail will be obscured by standing dead trees. I work my way back to the base of Cerro Rubio for my big ascent of the day.

Along the way: Wildflowers.

Obviously a legume, from the flower shape, but I had to look it up for more specifics: Probably golden pea.

There really isn’t a way up Cerro Rubio that avoids a maze of fallen trees.

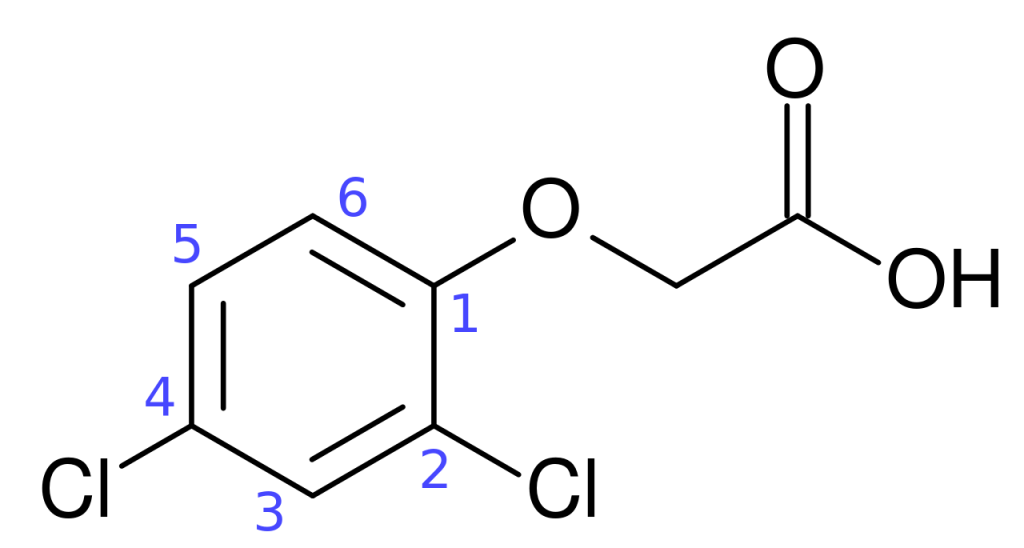

I slowly work my way up, coming almost at once to a new rock type that I figure must be Cerro Rubio dacite.

It turns out it is. This rock has a very characteristic fine-grained look from numerous small, almost equally-sized plagioclase feldspar phenocrysts. It looks bluish when fresh but weathers to a red color.

Geologists initially characterized this rock as quartz latite, a rock with equal quantities of plagioclase and alkali feldspar and 5 to 20 percent quartz. It was not immediately radiometrically dated, and its field relationships (which other formations it lies on top of and which lie on top of it) were misread such that this was assumed to be a quite young eruption, perhaps as young as 1.1 million years — postdating the Valles eruption. When it was finally radiometrically dated, it was found to be 3.56 million years old and to have a dacitic composition, making it part of the Tschicoma Formation. In fact, it is now recognized to be the southwest buttress of the Toledo Embayment. I figured it was still worth a visit.

But the going is awfully, awfully slow, with all the fallen trees. I do a lot of weaving to avoid having to do much ducking, and finally work my way up to where the view opens up a bit.

Still a lot of standing trees in the way. I’ll save the description of the view for later.

The ground is increasingly covered with dacite boulders.

High-silica domes tend to be rubbly like this. The lava is so viscous that it does not come out a vent on top and run down the sides of the dome; rather, the dome is inflated with fresh magma from inside. Like bread rising, the outer crust stretches and cracks, forming lots of easily-eroded debris.

My hope is that I will strike a bare rubble field further up from which I will have a marvelous view. These bare rubble fields are likely where Cerro Rubio, “Blond Hill”, got its name.

And I reach a fence.

This is apparently the county line between Los Alamos County to the east and Sandoval Country to the west. Yes, apparently, someone saw fit to fence that boundary, here in the middle of nowhere. I speculate that this is because it’s only a couple hundred feet east of the Valles Preserve boundary, which it parallels, and served for both at one time. However, this fence is clearly no longer being maintained.

I cross easily and soon see another fence.

This is newer and marks the preserve boundary. I hesitate; I haven’t bought my season pass for the year yet. But there’s no one here to buy a pass from. I cross and continue.

The rubble field comes into view beyond the shrubbery.

I’m soon there.

This is an example of a lag field. The soil and smaller bits of rock are carried away by the elements, leaving only the larger boulders. In some places, lag fields became so icy during the last Ice Age that they were mobilized as rock glaciers; but I see no signs of glacier flow here.

Signs of flow banding in a boulder.

The bedding is stretch marks from the dome being inflated from within. The crust of lichens over most of this boulder field shows that it has not been disturbed in a very long time; possibly centuries.

I’m high enough to try another panorama.

I had hoped to get one for the book, but there are just too many trees in the way, and it’s clouding up. Still. At left is Quemazon Peak, then Pajarito Mountain with its ski runs in shadow near center, with the caldera rim in front. At right is Valle de los Posos, with Cerro del Medio at right and the south caldera rim beyond them.

A closer shot of the Bandelier Tuff bench forming the east caldera rim. This is one for the book:

I climb a little higher and try again.

That may be okay for the book. At left is Quemazon Mountain, then Pajarito Mountain left of center with the bench of Bandelier Tuff on the caldera rim below it, then Valle de los Posos to the right with East Posos on the near side and Cerro del Medio on the far side, and the caldera rim on the skyline behind them. That’s Redondo Peak at far right partially obscured by the tree.

Valle de los Posos again.

The bench again. This shot may be slightly better.

I consider. It’s 11:30. I could climb for another half hour according to my time budget. But it’s not clear time is now the limiting factor; it’s clouding up and there may be lightning risk. Also, I’m feeling pretty tired by this point, and tired means more likely to injure myself. I climb a few more feet to see if there is really a better spot higher; it doesn’t look like that’s a sure thing. (Looking on the map after I get back, I see that I could have had a pretty good view further up, but it would have meant crossing a bare boulder field a over considerable distance, and while that’s not as bad as the crossed fallen trees, it’s still hard work and treacherous.)

I decide to call it a day.

I pause for a sample. Wait, I’m still on the Valles Preserve side. Yes, I’m scrupulous about not collecting on the Preserve. I cross the wire fence and grab my samples.

The first is definitely Cerro Rubio dacite.

It has a characteristic bluish tint and a “salt and pepper” appearance from many small crystals of quartz and feldspar. These sparkle in the light. There is also a single large feldspar phenocryst at top.

The other sample was, I though, deeply weathered dacite.

But I’m not sure. This rock is oxidized all the way through, it’s easy to break compared with the rather tough dacite, and it actually looks a lot like Bandelier Tuff. Remnants of a thin mantle of tuff atop the dome?

Getting back down is very tiresome. In some ways, it’s harder than going up. But just as I’m wondering if the fallen trees will never end, I abruptly hit the trail.

I’ve drifted a long way east; the grain of the fallen trees kind of drove me that way. But I’m on the trail and it will be much easier going the rest of the hike.

I see another side trail to the rim and try it. Alas, it doesn’t give any clearer view than I’ve had already.

Cerro Rubio at right. The more distant mountain is Posos West. It’s underlain by rhyolite 1.54 million years old, and it’s interpreted as a ring dome of the Toledo caldera that formed before the Valles caldera and is guessed to have been about the same size and in the same location. Posos East, out of view to the left, is slightly younger but has the same interpretation.

I get a picture of a Tsherige Member outcropping in the trail across the bench, and also take a sample.

The sample:

This looks like a densely welded tuff, where the pyroclastic flow settled to the surface while the volcanic glass shards were still soft, and they flowed together. There are lots of crystals of feldspar and quartz.

I arrive back at the dacite flow along the trail I mentioned earlier. Now I’ll investigate it in earnest. I scout up the slope and find a solid outcrop.

I try to hammer off a sample. Holy colorful metaphor, this stuff is tough. If I had any lingering thought this might be Tsherige Member, they’re put to test; no tuff is this hard. I have to try several outcrops before I find one I can get a decent sample from, and it’s more weathered than I would like.

Significance? The Upper Quemazon Canyon flow is a fairly small one, but at 2.92 million years in age, it’s one of the youngest in the Sierra de los Valles, and it seems distinctive enough from the underlying Rendija Canyon flow to be worth mapping separately.

I arrive back at Canada Bonita. The climb up to it was difficult; I’m quite tired by now and my left boot tends to rub my heel badly on uphill climbs. But I hike to the west end of the meadow, passing the very porous Valles Preserve boundary fence and following a faint trail. Alas, the view is still not clear.

Look, I really do understand that it’s a good thing the recent fires did not leave a completely barren landscape. I’m just slightly disappointed that, with the damage so severe, it wasn’t quite sever enough to fully expose the geology. Might as well be hung for a sheep as a lamb.

At left, behind the trees, are the north slopes of Cerro del Medio. In front is Valle de los Posos. The mountain just left of center is Cerros del Abrigo. The mountain on the skyline just right of center is Cerro de la Garita, the high point of the caldera north rim. The hill hidden in the trees at right is Posos East.

I look around a little but it looks unlikely I’ll get a clearer view anywhere nearby.

As I continue on, a pair of bikers pass me. It’s the first people I’ve seen since Guaje Overlook. A little further along are a couple with a pair of dogs. I’m very fond of dogs, and most sense it within about five seconds; these are no exception and they make friendly with me.

Three final shots. A cliff of dacite along the trail.

This shows the kind of high-aspect flow that is produced by very viscous silica-rich lava.

Looking down Los Alamos Canyon.

Mafic inclusions in a dacite boulder.

“Mafic” means rich in iron and magnesium. There are mafic inclusions in Tschicoma Formation rocks north of Tschicoma Mountain, which have been interpreted as evidence of magma mixing — blobs of more iron-rich magma entering the magma chamber and not quite mixing with the rest of the magma. But these look more like bits of country rock caught up in the magma. I suppose it could just be differential weathering.

I get back to my car. Someone has placed cones all around this side of the parking lot, marking it as a bus stop; they weren’t there when I parked. No ticket on my car, fortunately. I load up and return home.