Fall is coming fast

We had a bit of a cold snap this week.

No, that’s not normal for early September in Los Alamos. The local paper reports that this is the earliest snow in 105 years.

It warmed up again fairly quickly, though, and on Friday I did some local hiking just to get a feel for how quickly the roads were drying out. (So I’d make the right plans for Saturday.)

First stop was the zeolite ledges in Ancho Canyon.

The rocks here are part of the Tshirege Member of the Bandelier Tuff. For new readers (Welcome!), the Tshirege Member formed from a mixture of hot gas and volcanic ash erupted from the Valles caldera 1.25 million years ago. This mixture flowed like a fluid (a pyroclastic flow) for miles in all directions from the caldera, then settled to the surface and hardened into solid rock.

The ledges here formed later, when the nearby Rio Grande River was dammed by landslides in White Rock Canyon to form a lake. The ledges mark different stands of the lake, and formed where the water penetrated the porous tuff, picking up silica and alkali, and then was drawn by capillary action into the overlying tuff to deposit the dissolved solids as minerals called zeolites. These acted as a kind of cement that hardened the tuff at the water interface, making it unusually resistant to erosion, so that the zeolite ledges here stand out. I took a sample, but the zeolite is too fine-grained to be easily discernible in the rock.

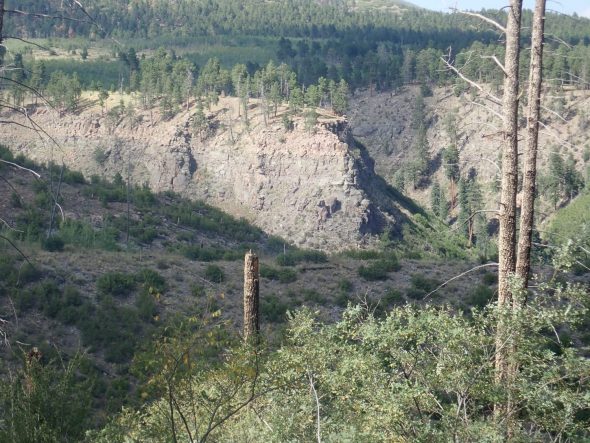

Above here is a slot canyon into the mesa, which ends in a kettle.

The rim is a particularly hard bed of Tsherige Member, probably the lower “C” bed. Water coming over the cliff hollowed out the kettle beneath.

Some interesting tuff here.

This is probably weathered from the softer upper “C” bed. It’s got some pumice in it, and also some fragments of pre-caldera volcanic rock, likely torn loose from the sides of the eruptive vent. This is fairly common in the “C” beds in the White Rock area.

This ain’t natural.

Doubtless a relic of road building in the area, though I don’t know precisely what kind of heavy machinery leaves a mark like this.

I’m mostly out here to see what the roads and trails are like (they’re drying out rapidly, as it turns out) but I find myself wandering up towards American Springs. I decided to get my daily walking exercise here, and find myself on the south rim of upper Water Canyon. I’ve seen the red cinder beds here before, but the light wasn’t nearly as good for photography then. Not that it’s ideal know; there’s just enough scattered cloud that I have to time my shots.

For new readers: Almost every image at this site can be clicked for a higher-resolution, and almost every blue link takes you to the location on Google Maps.

The red beds are quite striking. I hiked in once and took a sample; it’s pumice high in iron minerals that has been thoroughly oxidized. Pumice makes an excellent aquifer, and shallow groundwater percolating constantly through such an aquifer is excellent at rapidly oxidizing minerals. However, I’ve yet to find any geologic report on the Jemez that mentions these beds, which quite surprises me.

Down canyon, we see the contact between the “E” and “F” beds of the Tsherige Member.

If you look close, you can see a rim of pink tuff over grey beds further down. The pink tuff is quite typical of the Tsherige Member, but the grey beds are only found in a few locations, like this one, close to the caldera. There are some unusual chocolate brown beds of tuff just west of the caldera rim, as well, which I tentatively identify as part of the same pulse of unusually iron-rich magma.

I’ve mentioned lettered beds of the tuff a few times. These were first described by a Los Alamos geologist, Margaret Rogers, some years ago. The lower beds seem to be more extensive; near my home in White Rock, only the “A” and lower “B” beds are present. Further north and west, the “C” bed is present, and most of the Los Alamos town side sits on the “D” bed. The “E” and “F” are found only in the westernmost part of the Pajarito Plateau. If I’m not completely off on my reckoning, the gray beds here, which are prominent where State Road 4 climbs the Pajarito escarpment, are the “E” beds, and the pink beds on top are the final “F” beds.

There is some debate whether these represent actual individual flows. That’s surprisingly hard to be sure of.

Further down canyon:

This is probably one for the book. The contact is not quite as clear, but clear enough, and you can see the ledges marking the “D” and “C” beds below. There’s no sign of the red cinder here; it seems to be a very local feature.

I hike down to the escarpment, just for the view.

There seems to have been a lot of recent wood cutting in this area.

The roads looked like they would be fine, so Saturday was more type section photography. A type section is where a geologic formation is first defined and described, and I’m taking the photos mainly for Wikipedia. Last week it was the Ceja Formation type section; this week I’m doing a twofer.

The first is the Arroyo Ojito Formation. This has no proper type section, just a type location, which is on Zia Tribe land north of the Ceja Mesa escarpment near Rio Rancho. Northern Ceja Mesa is kind of a funny area; some developer has already laid out miles of suburban roads that he presumably thinks will become miles of suburbs someday. Perhaps this is not so ridiculous; Rio Rancho is one of the fastest growing cities in New Mexico. The roads are not yet paved and the utilities aren’t yet installed, but they’re pretty good roads, for gravel roads. The main road is Rainbow Boulevard, which heads more or less directly northwest to the escarpment.

The road crosses a barbed wire fence just south of the escarpment where you enter public land. The escarpment itself is the boundary with Zia Pueblo land, except for this one area, where, for reasons unknown, the boundary is down in the badlands below the arroyo. I intended to restrict my hiking to public land and not encroach on the pueblo; but, as there are no markers on the boundary, I may have encroached slightly. Well, let’s hope “no harm, no foul” applies here. My visit was brief and nondestructive.

My photo shows the Wandermobile contemplating the view to the north. Which is spectacular:

Almost everything down there is the Loma Barbon Member of the Arroyo Ojito Formation. Further north, the Navajo Draw Member is exposed, and some of the beds immediately under the mesa rim may be Picuda Peak Member. I’m not sure I can reliably tell them apart; I’m still polishing up my skills at identifying formations, and the distinction between different Rio Grande Rift fill sediment formations can be pretty subtle.

Unpacking that: The Rio Grande Rift is a great crack in the Earth’s crust extending from central Colorado to the El Paso area, much of which coincides with the Rio Grande valley. It’s where the Colorado Plateau is pulling away from the High Plains. The Rift is full of sediments eroded off the bordering highlands, and these sediments are assigned to a number of geologic formations grouped together as the Santa Fe Group.

Here in the northwest Albuquerque Basin, the oldest Santa Fe Group beds are the Zia Formation, which is overlain by the Cerro Conejo Formation, which is overlain by the Arroyo Ojito Formation, which is overlain by the youngest Ceja Formation. There are subtle differences in the makeup of the sediments that distinguish each formation, and each formation is further divided into members based on even more subtle differences in the makeup of the sediments.

I have a published guide to hiking the area but I left it at home by mistake. I recall that it says to hike northwest along the escarpment to a knife edge ridge that goes down into the badlands, and there’s a kind of tent rock that sits very close to the Zia boundary is that you shouldn’t go past. Well, I see the knife ridge, all right, and head that way.

Beautiful view of the beds. This one is for the book.

Zooming in to the beds on the rim to the west. I’m hoping this is Cerro Conejo Formation at its type area.

When I get home and check the geologic map, I’ll find that this is indeed a different formation from the Arroyo Ojito — but it’s marked as the Chamisa Member of the Zia Formation.

Or so the draft map says. The Cerro Conejo was once assigned as a member of the Zia Formation. And there is supposed to be a prominent ash bed within the Cerro Conejo; you can see a white ash bed here. So perhaps the map is mislabeled.

If so, the ash bed is from a ginormous eruption of the Yellowstone hot spot and is around 11 million years old. So says the geologic report.

Visible to the north is White Mesa.

The white is the Todilto Formation, a gypsum bed formed by prolonged evaporation in a shallow sea. Beyond is the main block of the Sierra Nacimiento, with Pajarito Peak forming the high point at left. Below, and to the left of White Mesa, is Red Mesa, which looks like a gentle swell from this side; it’s quite steep on its west side, along the Pajarito Fault. The low ground just beyhond White Mesa is Jackrabbit Flats, and the ridge to the right of White Mesa is Chuchilla Mesa, whose east side is the San Ysidro Fault. Lots of tectonics in this photo.

I start down the knife ridge.

River gravel. There’s been a lot of regional uplift and erosion along the Rio Grande, but a sizable river once flowed here. The gravel includes both quartzite and granite likely from far north, and basalt likely from the Jemez or Santa Ana volcanic fields much closer. So fairly young gravel.

I’ve donated this one to the public domain for Wikipedia.

No, not quite as good as the previous, but I don’t think anyone can blame me for keeping the very best shots for the book.

I finally find a way down the knife ridge to the arroyo below. Looking back up the way I came:

I hike some distance along the arroyo, but never come to the tent rock I expected that marks the Zia Pueblo boundary. I eventually become concerned I’ve already crossed the line, and turn back.

Out of respect for the pueblo, I won’t post pictures that I may have inadvertently taken while north of the line. I’m confident this one was south of the line.

This shows Arroyo Ojito formation beds in the side of the arroyo. Layers of fine dirty sandstone with some gravel and mudstone.

Looking at the guide after I got home, I found that the description of the route was awfully vague, but I likely came the wrong way.

Hiking back involved looking carefully for my own footprints to be sure I didn’t take a wrong turn. At one point my tracks vanished on ground that was far too soft not to show tracks, and I doubled back until I found my tracks headed up a different branch of the arroyo. And I had to guess where I finally went back up the knife ridge; my tracks disappeared but I couldn’t find where they left the arroyo. Turns out I was not far off. Anyway, there’s no way to miss the knife ridge if you just head generally south; it’s just a case of finding the easiest way up.

At the top: There are a couple of young women with a high-power rifle having a great time. One asks me if that’s my car.

Why, no. No, fortunately, not.

I head to the Wandermobile and find their car parked just behind it. Maybe it was a straight question after all. I eat my sack lunch to the accompaniment of an occasional rifle shot and, at one point, a loud “Got him!” Then back down the road. I take the wrong one at first but the road is lousier than I remembered and my car compass says SW when it should say SE, so I soon correct my error. Then off to a road cut in the Cerro Conejo Formation.

Whereas my previous destination was in the middle of nowhere, this one is on a busy highway, and I have to take care parking and getting across for the photo. Also, this is not the type location; it turns out the type location for this formation is on Zia Pueblo land. Zia Pueblo has been good about giving real geologists access for mapping, but I’m not a real geologist (I only play one on the Internet) and I’m going to settle for a good exposure somewhere in the general neighborhood of the type location.

This is my keeper photo. I put a slight different photo on Wikipedia.

Then home via La Cienega, where I do a little hiking to check out one or more two things before my presentation Tuesday. Don’t want to spoil that so I won’t post pictures yet.

And the Wandermobile is now within 700 miles of 200,000 miles. It’s been an absolutely wonderful car; I seriously hope to get many more miles out of it, with proper maintenance.