Coronavirus-Restricted Excellent Adventure, Day 5

Morning in the wilds outside Deming, New Mexico.

We breakfast, pack, and drive to Rock Hound State Park. We paid the overnight camping fee last night, though there turned out not to be a camp site; we might as well get part of our money’s worth by hiking there today.

Florida Mountains to the south.

The northern portion we’re looking at here is relatively young volcanic rock. The southern part of the range is Paleozoic batholith rock, solidified from great masses of magma deep underground in the Cambrian or Ordovician (540-450 million years ago.)

The Little Florida Mountains:

Geologically, these are similar to the northern part of the (Big) Florida Mountains. Volcanic rock, a bit younger and richer in silica. The eastern slopes, not visible here, are young sedimentary beds, suggesting that these mountains were thrown up by tectonic forces in the last 30 million years. That’s young by geological standards.

Gary is ready to hunt jasper.

Rock Hound State Park boasts that it is one of only two state parks in the country that allow rock collecting. Well, a little bit of rock collecting, anyway. Apparently there used to be a bag limit of 15 pounds a day; now they say “a few pieces”. I suspect some people were abusing the privilege. See, this is why we can’t have nice things …

I’m surprised how green the area seems.

Yes, it’s cactus and yucca, but so green. It was the same with the yuccas on the “reef” yesterday.

Jasper.

This is extremely fine-grained quartz rich in hematite, ferric oxide. We spend a fair amount of time collecting specimens. I decide that if I can comfortably carry all mine in one hand, then I’m within the limit of “a few pieces.”

Cactus.

These were not uncommon in the area. Fishhook barrel cactus, Ferocactus wislizeni, if I’m not mistaken. Surprisingly, it can survive temperatures down to 5 Fahrenheit. The yellow cones on top are the fruit, which remain attached to the plant for an unusually long time.

My original plan was to head to Columbus then east to Kilbourne Hole, skirting hte Mexican border. We take a paved road into the Florida Mountains in hopes it heads that way; if not, at least we’ll see some nice scenery.

The sign says:

LOVERS LEAP TRAIL 0.9 MI

VERY STEEP GRADES AHEAD

That seems very believable.

The road ends here. We turn around and drive back into Deming. We need to refuel and we’re both tired of camp cooking; we decide to risk getting some fried chicken from KFC. Gary also wants to make a gift to me of a duffel bag and some plastic bins; my stuff is in several bags scattered all over the back of the car and I agree it’s awkward.

The chicken is wonderful. I decide I’m on vacation and can relax the diet briefly, and eat the buttermilk roll. I eat some of the fries as well. It’s a big carb dose but this is a once in a great while thing.

We want to get to Kilbourne Hole, a large maar (shallow eruptive crater) west of the Las Cruces – El Paso corridor. We’ve abandoned my original route and decide to go in along the interstates, first east along I-10 then south to where I hope to pick up the directions in the road log. The trick is to avoid entering Texas, so that my travel remains in-state, but the road log we have for this part of the trip quite reasonable assumes you are headed south on I-25. The trick is to stay out of Texas while not getting lost. We stay way west in the Rio Grande valley, passing through pecan and peach orchardes, and I put us on what seems like the right road back west into the desert. We are soon at the edge of a gaping crater.

Kilbourne Hole, and Hunts Hole to its south, are maar craters, thought to have formed when rising magma hit sedimentary rock saturated with groundwater, and the result steam explosions blasted a big hole through the overlying sediments and lava flows. Debris rained down around the rim, including chunks of rock from the lower crust and upper mantle. These are particularly interesting since we cannot possibly mine or drill the 30 kilometers down to reach the mantle and collect samples. We have to collect the samples Nature sends us.

In the distance, a lava flow through which the crater was blasted.

This is apparently part of the Aden-Afton basalt flow, which is young enough to be difficult to date; the estimate in our road log is around 100,000 years. The crater itself is somewhere between 24,000 and 80,000 years old, depending on the method used to try to date it.

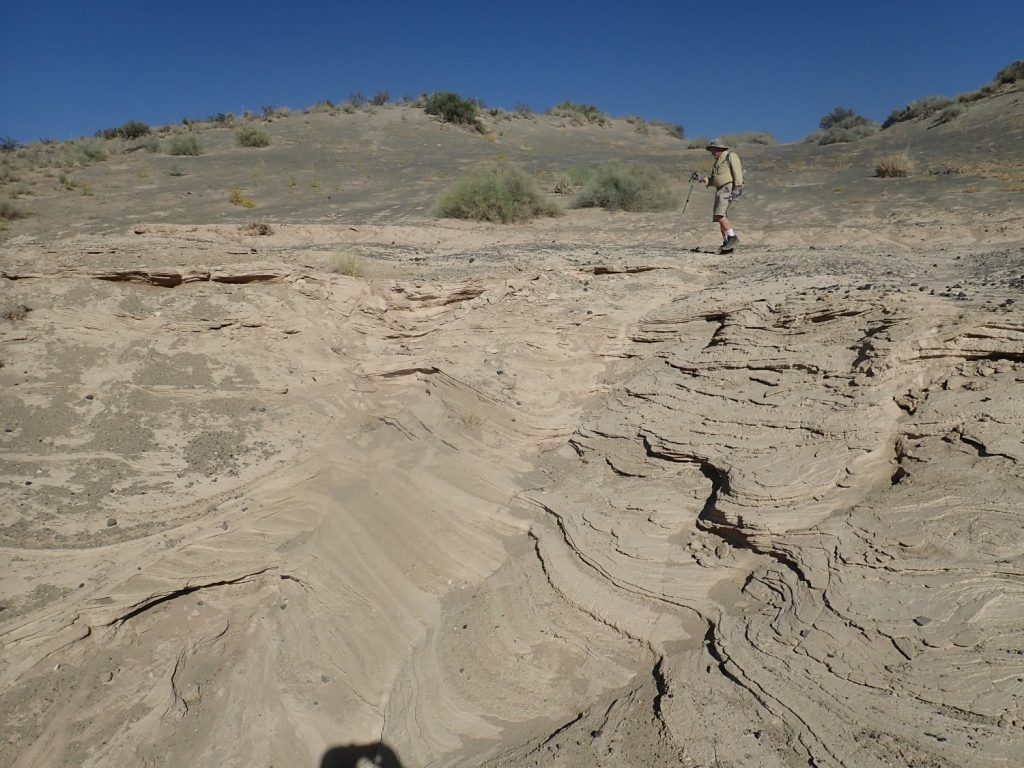

We descend across phreatomagmatic beds. Phreatomagmatic: Resulting from contact of magma with a saturated aquifer.

The thin beds suggest that there was not one big explosion here, but a long series of smaller explosions. This is pretty typical of maars.

Contact of the phreatomagmatic beds with the underlying Santa Fe Group sedimentary beds.

Fox skull.

The basalt flows here seem very young, consistent with the age estimate of less than 100,000 years.

More phreatomagmatic beds.

Crystal casts? Of gypsum?

I’m beginning to feel frustrated. Kilbourne Hole is famous for two things: drop stones in the phreatomagmatic beds, and mantle xenoliths. So far I haven’t spotted any examples of either. All I can find are some crustal xenoliths, such as this sandstone chunk:

We hike back to the car and head north, along a road Gary has Googled up as the fastest way out. We pass another car, not unlike ours, with luggage bag on top and a woman behind the wheel sporting a huge grin. Well, it is fun to be out here, though I’m still feeling frustrated.

To our surprise, we come across another humongous crater. I laugh out loud. We must have taken the wrong road; we were at Hunts Hole, not Kilbourne Hole, and Hunts Hole is a bit smaller and has no xenoliths. No wonder I couldn’t find any.

It is late. We decide we’ll camp nearby and make a long drive in the morning.

After setting up camp, we climb back into the crater to explore. The rim is quite steep, and shows signs of having been popular with dune buggy drivers.

Panorama.

Phreatomagmatic beds, again.

Sitting on red Santa Fe Group beds.

Gary calls out. He’s found a dropstone.

It’s the very one shown in our log book for this area. This big chunk of basalt was thrown out by the eruption, fell on the soft sediments, and made a pretty good crater . This was subsequently filled in by more phreatomagmatic deposition.

Nearby, a drop stone has disappeared but left part of the deformed beds behind.

Contact of the basalt flow with the underlying rock.

The basalt was deposited on a flat surface of thin soil over a caliche (calcrete) layer formed by groundwater being wicked up near the surface and depositing lime. This is a pretty good description of a lot of the modern terrain around here.

We descend into the crater.

Phreatomagmatic beds over Santa Fe Group.

I am scouting for xenoliths. This, maybe?

Possibly a shallow crust xenolith. I’d like to find the really deep stuff.

This?

The rock seems unusually heavy and it looks crystalline. Alas, under the loupe, I see that a fresh surface is all glassy beads — basalt glass. It’s moderately unusual but it’s not a xenolith. Shucks.

Frustrated again at not finding any mantle xenoliths, we start back. Snake track:

Camp.

I consult the road log. The xenoliths are mostly on the east and north rim. Maybe we just picked a bad place to hunt. We’ll try again further north in the morning before heading home.

Next: Xenoliths’R’Us and green chile cheesburgers