90th Birthday Wanderlust, Day 7: Temple Mountain

Breakfast, and then Gary heads out for Green River for some car needs. I don hiking gear and head north towards Temple Mountain, following an old jeep trail.

The petals and stamens immediately suggest something in the evening primrose clan, Oenothera. However, I can’t make a precise species match; the combination of rounded leaves and lobate flower petals doesn’t line up with anything in the guidebooks I have. Pretty regardless.

The rock is upper Chinle Formation. Also pretty.

I approach the big uranium mine from yesterday, but along a different road that runs to the shelf above the mine cliffs.

Temple Mountain peers over the cliffs. The mine itself is in the Moss Back Member of the Chinle Formation, a common target for uranium exploration. Most of the uranium was found in petrified wood deposits, common in this formation. Uranium-bearing fluids percolating through the decaying wood found a chemical environment in which the uranium precipitated out to replace the wood.

Cactus. Possibly Echinocereus.

Temple Mountain looms ahead.

The white upper part is massive Wingate Sandstone, the same formation that makes up much of the rock barrier of the San Rafael Reef. The lower red slopes are all upper Chinle Formation.

There is much evidence of former uranium mining in the area, such as these concrete cylinders.

I have no guess what they were used for. Or perhaps I should have looked more closely; what I’m taking for concrete might be cores of sandstone? Awfully big cores, though.

View down an unnamed canyon.

Old uranium workings.

I come across some sandstone that shows a yellow mineralization.

The yellow might be carnotite, an important ore of uranium. I’m not carrying a Geiger counter, so I can’t be certain.

The northeast face of Temple Mountain comes into view.

This is the location of one of several sinkholes at Temple Mountain. As with the sinkhole I saw yesterday, groundwater has dissolved out limestone beds in the subsurface, and the overlying beds have collapsed into the resulting sinkhole. Hydrocarbons rose into the collapsed rock beds to bleach them white. It seems likely to me that this process took place before extensive erosion in the area, and the bleaching process also increased the degree of cementation of the nearby rock. This helped to preserve Temple Mountain, preventing it from being eroded away along with the rest of the Wingate Sandstone west of the San Rafael Reef.

Sinbad Country.

The many low mesas of this region are capped with the Sinbad Member of the Moenkopi Formation. Beneath the cap are red beds of the Black Dragon Member of the Moenkopi Formation. Though not clearly visible from here, the gully bottoms expose the Kaibab Formation and, below that, the White Rim Sandstone, which seems to be the oldest formation exposed in the San Rafael Swell.

Panorama of the sinkhole area.

I am standing on a high escarpment. It looks like there may be a road down to the country below. I am tempted to find a path that will have me hike completely around Temple Mountain. However, my map is not detailed, and I decide that (while there is no real danger of getting lost) it may be more hiking than I care for. I turn back.

Beautiful view down an unnamed canyon to the distant country.

The butte in the distance is Gilson Butte, which is well out into the San Rafael Desert, one of the most remote areas still left in the lower 48 states. Gilson Butte is capped by Curtis Formation over slopes of Entrada Formation. Both are Jurassic formations, prominent at Arches National Monument (the famous Delicate Arch is eroded out of these two formations), and both were deposited in a great sand sea when this area was in the rain shadow of the Sevier Mountains in western Utah and in the arid belt just north of the equator. This would have been around 170 million years ago.

On the way back, I take a side spur of the road on the off-chance it passes closely south of Temple Mountain. It turns out that the road ends at a high escarpment. Panorama to the west:

On the way back, I look closely at the Painted Desert Member of the Chinle Formation.

This rock is thought to have been laid down in a monsoon climate. The tubelike structures may in fact be burrows of crustaceans or lungfish escaping the seasonal drought. Or them may be rhizoliths, structures that formed around plant roots. I think more likely the former.

Further south still, the structures are clearer.

The lack of horizontal branching suggests burrows rather than rhizoliths.

I think to myself that the road I am on is truly dreadful, hardly fit for jeeps, though there are tire marks suggesting that off-road vehicles (popular in the area) have been here recently. But shortly after I leave the road to strike out for my camp, I hear a roar of an engine, and a passenger van comes roaring down the horrid road I was just on, passengers screaming with delight at every bump. May I make an observation? You people are out of your minds.

Also, you kids keep off my lawn … 👴

I eat lunch, then head out for some more hiking. Last time Gary and I were here, I found a fairly cool fossil impression (it looked like a seed fern leaf) in the Moenkopi Formation, whose sandstone beds do not commonly preserve fossils. I head to the same area to see if I can get lucky again.

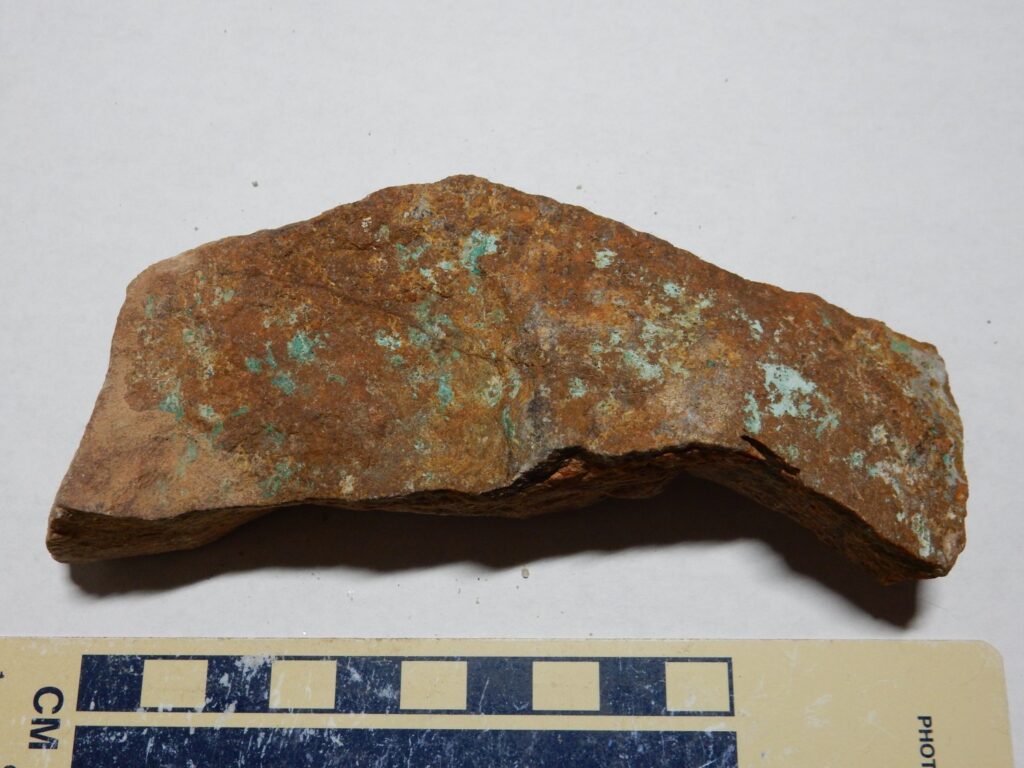

Copper mineralization:

Quite possibly turquoise, though low quality. The rock is a bit heavy to take with me.

This one was more practical, though this is probably just malachite rather than turquoise.

Chert in an arroyo.

Possibly a bit of petrified wood.

I find lots of ripplestone but no hint of fossil impressions. Too bad.

Next I try hiking into the eastern end of the canyon we’ve been camping in. There are some different formations here, and some native American petroglyphs.

“Color” in a shale bed at the contact between the Wingate Sandstone and the underlying Painted Desert Member.

A possible “supersurface” in the Wingate Sandstone.

I talked about these yesterday. The supersurface is a distinctive bed that can be traced for hundreds of miles, and it likely records a high stand in sea level. The sand supply to this area was cut off, and everything above the water table was eroded away. Then, with a drop in sea level and renewed sand supply, silty sand was deposited atop the old erosional surface.

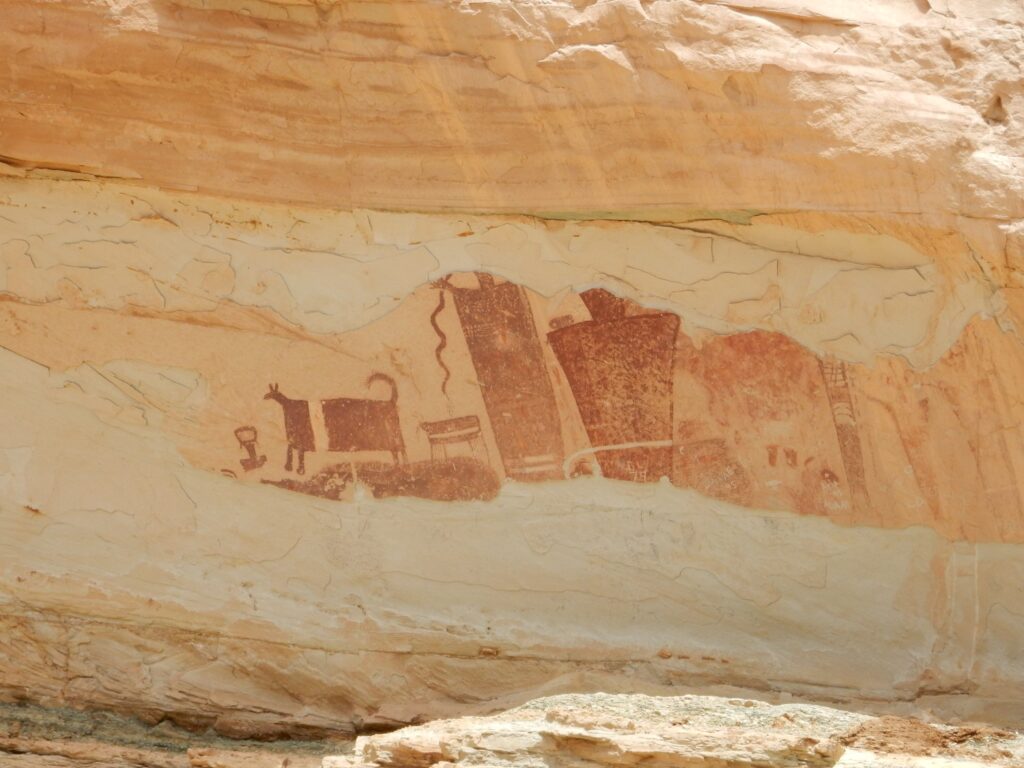

The petroglyphs:

These seem similar to me to the petroglyphs at Newspaper Rock well to the southeast, on the other side of the Colorado River, but quite different from those I’m acquainted with in New Mexico. I find it interesting that culture seems to have been exchanged across the considerable barrier of the Colorado River canyonlands.

The meaning of petroglyphs in my area is known for only a few petroglyphs. The meanings of others is either sacred to the artist and his tribe, or subjective to the viewer, or simply unknown to anyone now living.

Heading back:

From this angle, it’s easy to make out the thick stack of Kayenta Formation fluvial beds atop the massive Wingate Sandstone.

Gary returns from shaking down his vehicle. I discover we have miscommunicated: In my first itinerary, I had us spending this day traversing the northern San Rafael RIft, then camping near Buckhorn Reservoir. After my family’s plans gelled more, I changed this to visiting the reservoir, then Jurassic National Monument, then heading in to Provo for my family celebration. I gave Gary the revised agenda but did not think to call out this change. So Gary was still counting on camping at Buckhorn. Apologies, Gary.

We part ways here for the time being. Gary will camp at Buckhorn, while I will continue on in to Provo, and we will meet up again after my family party.

The road passes the type section for the Tidwell Member of the Morrison Formation.

At some distance, but via the magic of telephoto lenses …

The Tidwell forms the thinly bedded layers in the cliffs, under a cap of thickly bedded Salt Wash Member and over slopes of Summerville Formation.

Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation:

The camera loves this location. It turns out the photograph at Wikipedia (by a different photographer) was taken from almost an identical position and angle, but in better light.

The ledge capping the mesa behind is Buckhonr Conglomerate Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation.

I mentioned at the start of this series of posts that such a series was bound to include a lot of personal stuff. This begins here, because I next hurried to Provo to join the family celebration. Skip if you prefer. There will be significant geology the next few days, but interbedded with family celebration. I’ll try to place headers so you can skip the latter if you are only interested in the former.

Mom

The occasion for this trip was Mom celebrating her 90th birthday.

“When ninety years old you are, look so good, you will not, eh? Heh heh heh heh heh …”

I clean up from my trip, then take Mom over to my sister’s house for the opening banquet.

Almost the entire family is here. I could not bring Cindy and the kids; though now adults, the kids are in poor health, and Cindy hesitates to leave them to themselves for long. (Also, Cindy is in the middle of grading finals.) Susan’s daughter did not want to miss work and school. And one of the grandsons-in-law is on business travel. Pretty much everyone else is here.

Lori is swarmed with grandkids.

The grandkids all go out for a grandkid activity (an escape room) and the kids and Mom yammer into the night. We’re Grimmetts and we can talk forever…

But Mom tires, and I take her home and we turn in for the night.