A day at the museum

On Saturday, the Los Alamos Geological Society took its field trip to the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. This was in lieu of a field trip to a geological site, necessitated by the closue of most public lands due to fire danger. (That danger has since mostly passed; more below.)

I left early to attend a service at the Albuquerque Temple, then got some lunch and found the museum. I was quite early and took some time to admire some of the displays. This is the centerpiece of the main lobby:

This is a recreation of the Bisti Beast, Bistahieversor sealeyi, a relative of T. rex discovered near the Bisti badlands of the San Juan Basin in northwestern New Mexico. The model here is animated, moving around in a very realistic manner and roaring when suitably triggered. This was great fun for the kids, including this 60-year-old kid.

Eocyclotosaurus, a giant amphibian of the Triassic of New Mexico.

Smithsonite, zinc carbonate:

Alas, my photo that included the label did not come out, but it’s from a New Mexico mine whose named sounded familiar enough that I think the Society has visited it on field trips. (Though I haven’t been along myself yet.) Possibly the Kelley Mine near Magdalena?

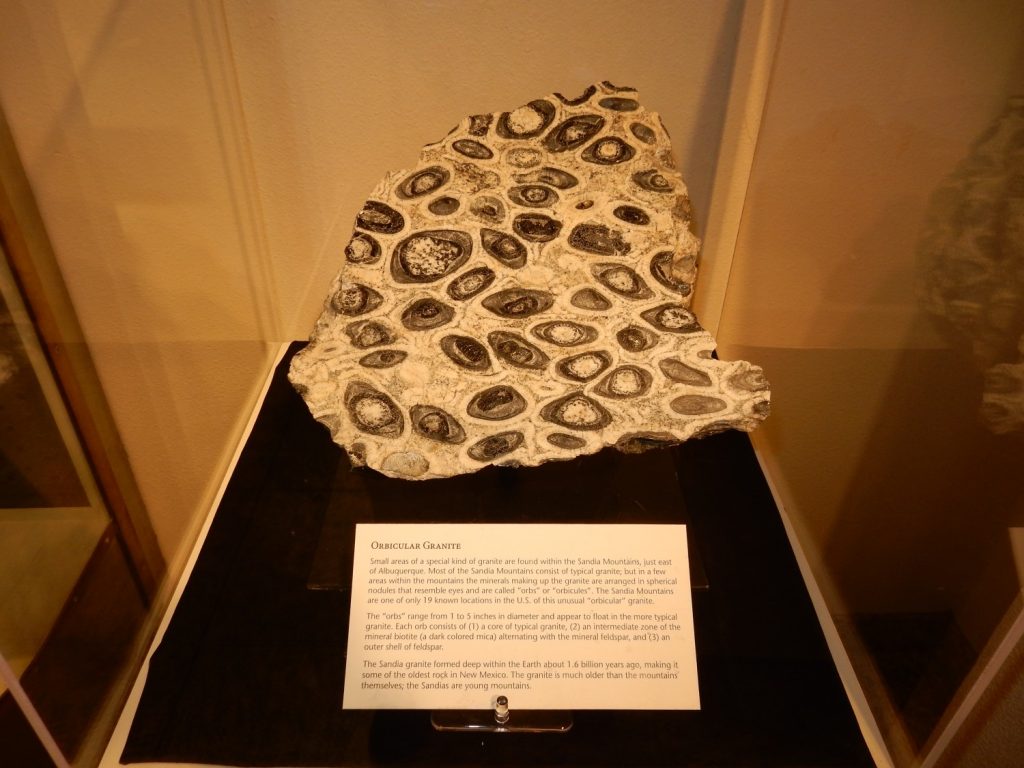

Orbicular granite from the Sandia Mountains. The Sandias are one of just a few places where this stuff is found.

I broke my ankle once trying too hard to find an outcrop of this stuff.

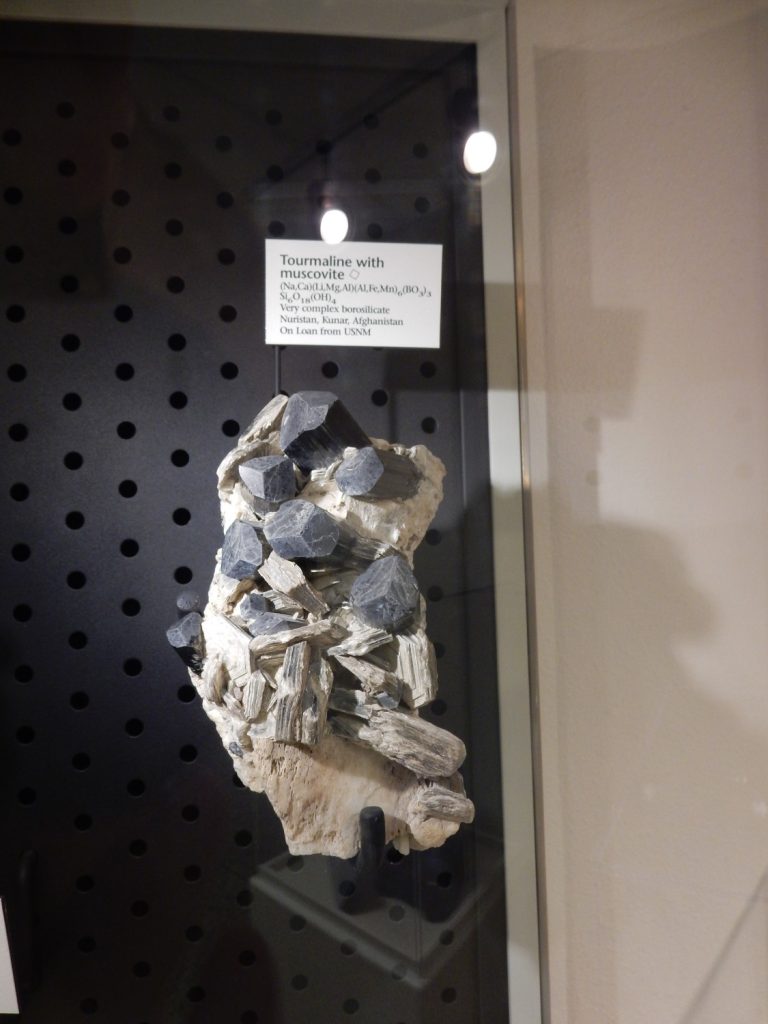

Tourmaline with muscovite.

Tourmaline is a boron mineral common in pegmatite. I have some nice samples but nothing as spectacular as this. Muscovite is common white mica.

Epidote.

Ditto. This is a common mineral in metamorphic rock, but stuff this well crystallized is very rare.

Hermimorphite, a hydrated zinc silicate.

A hydrous zinc silicate. It looks a lot like the smithsonite, doesn’t it? Zinc is almost always in the +2 oxidation state in nature, and this ion is generally colorless. Just winging it here, but i’m guessing the blue-green color is from traces of copper substituting for the zinc.

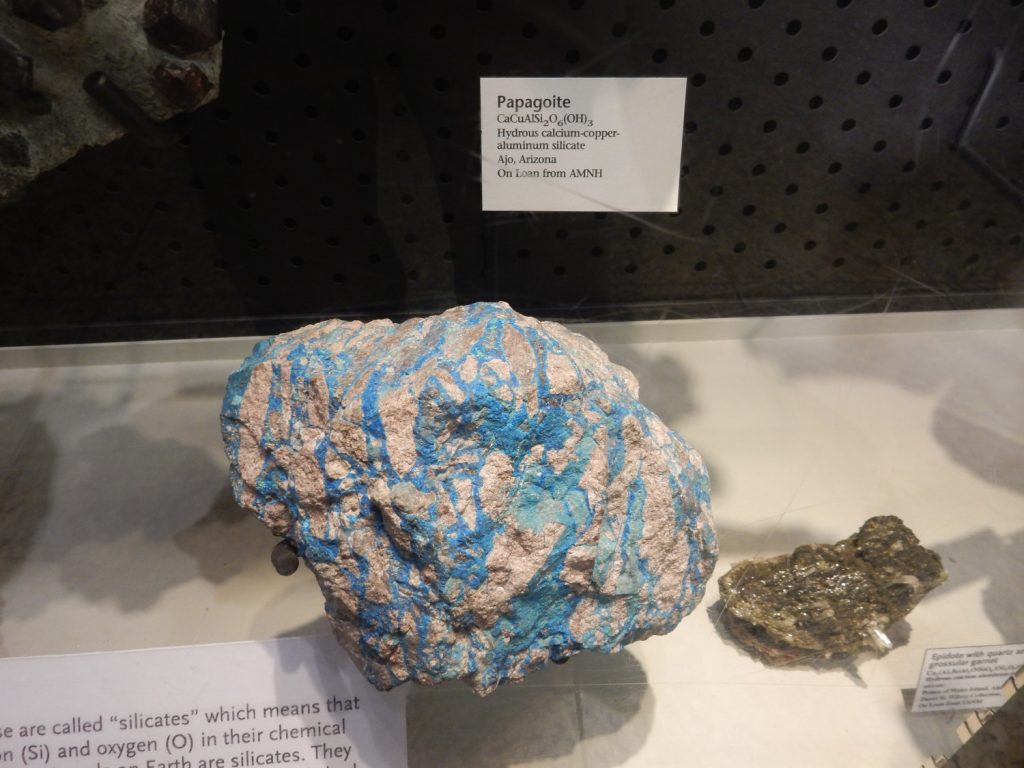

Papagoite.

This is a little like turquoise, but a silicate rather than a phosphate, and I’ve never heard it has any jewelry value.

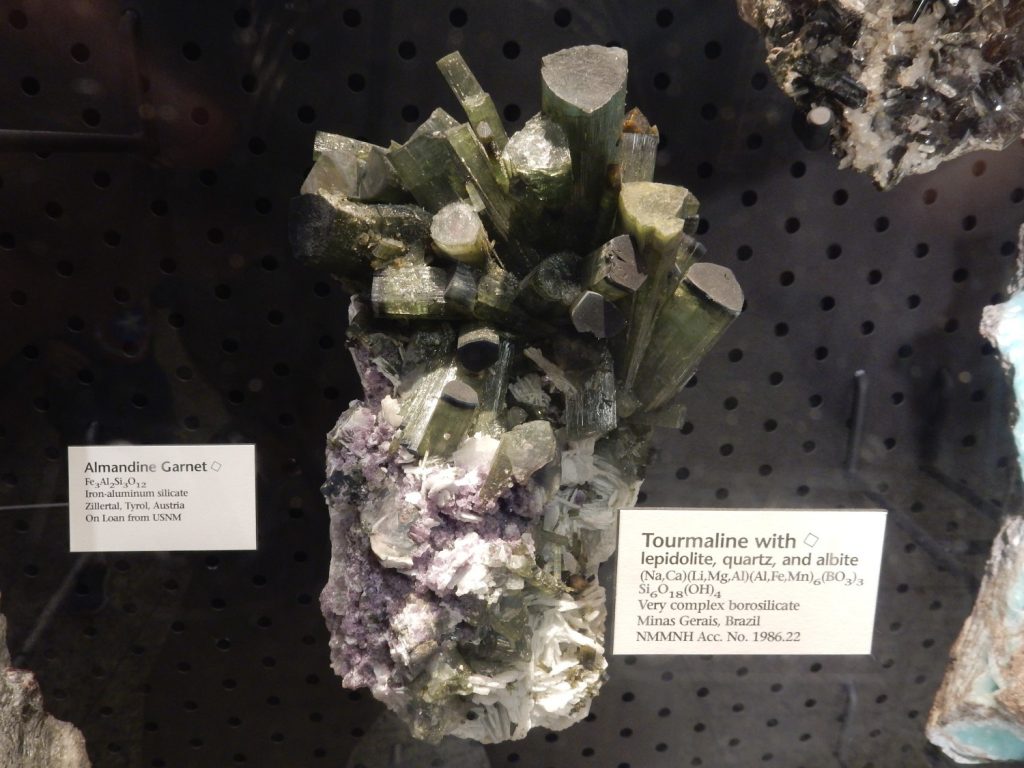

More tourmaline.

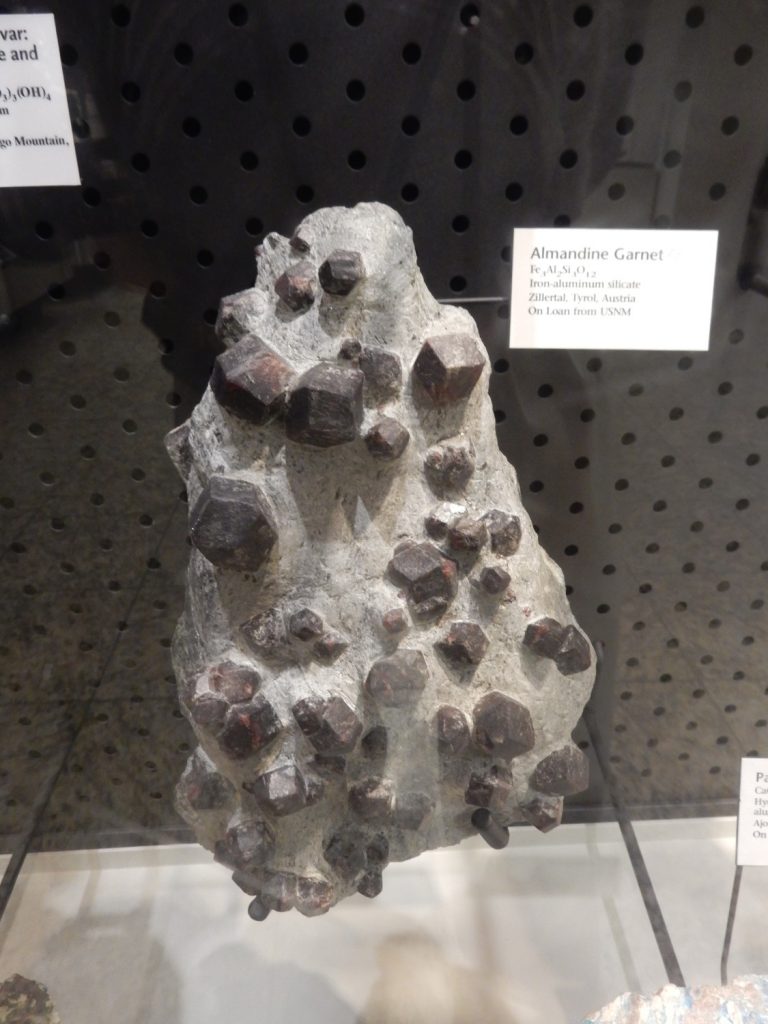

Almandite garnet.

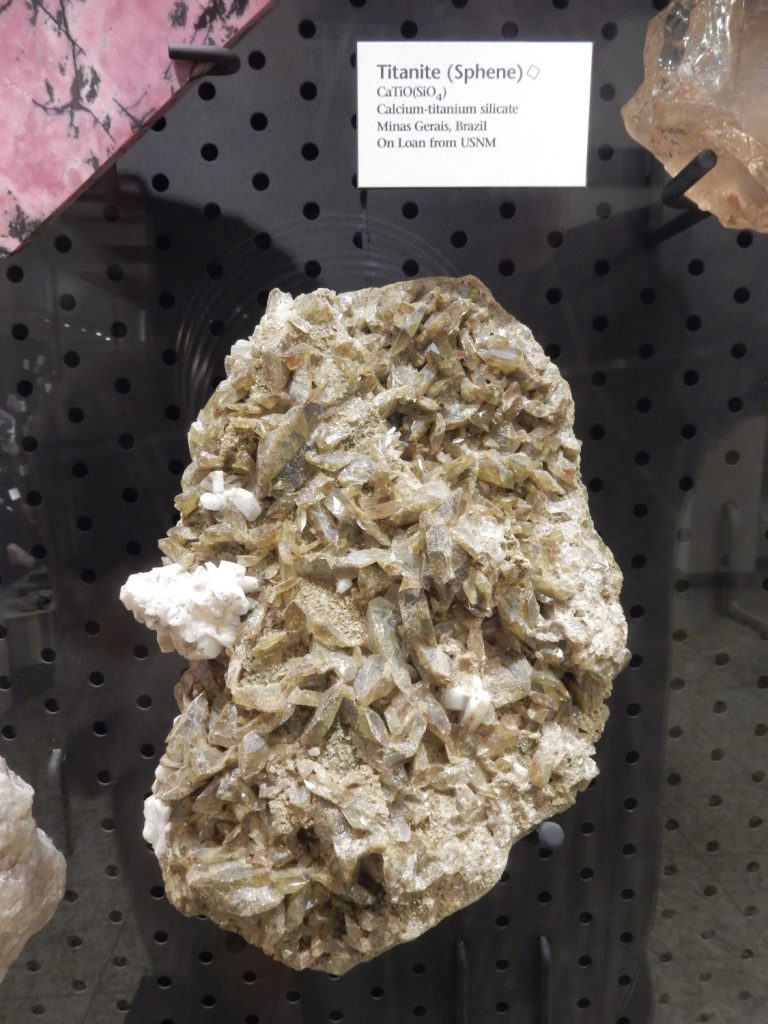

Titanite.

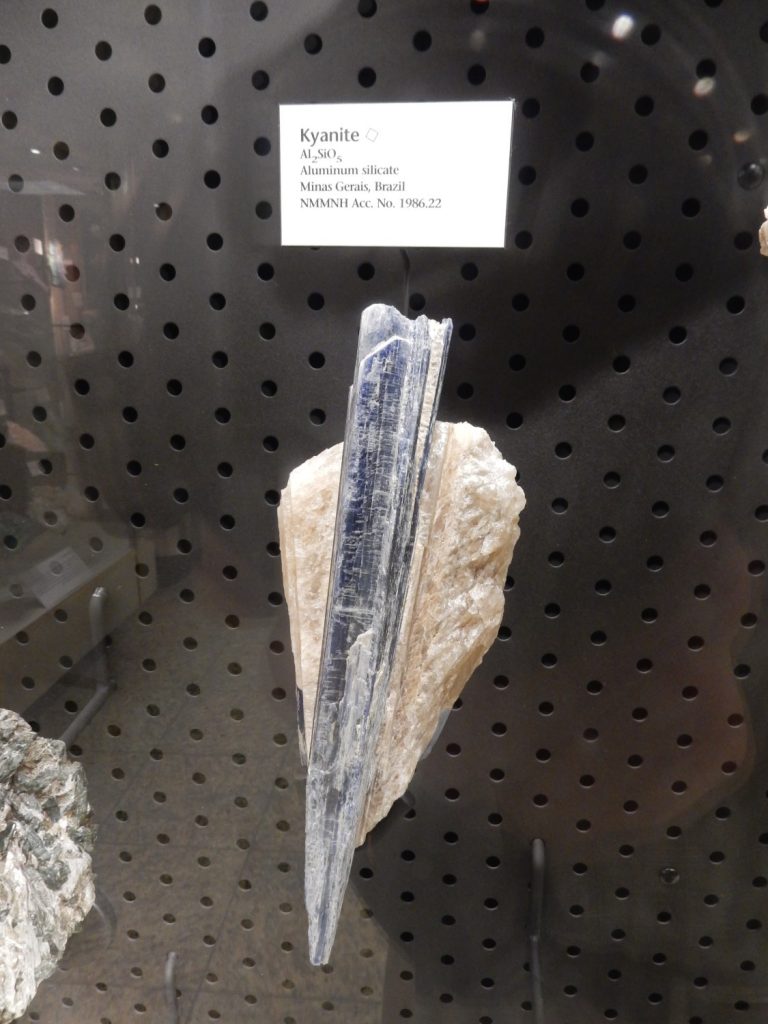

Kyanite.

Blue crystals of kyanite, an aluminum silicate, are not too hard to find in rock shops for a reasonable price, but this one is unusually large and well-formed.

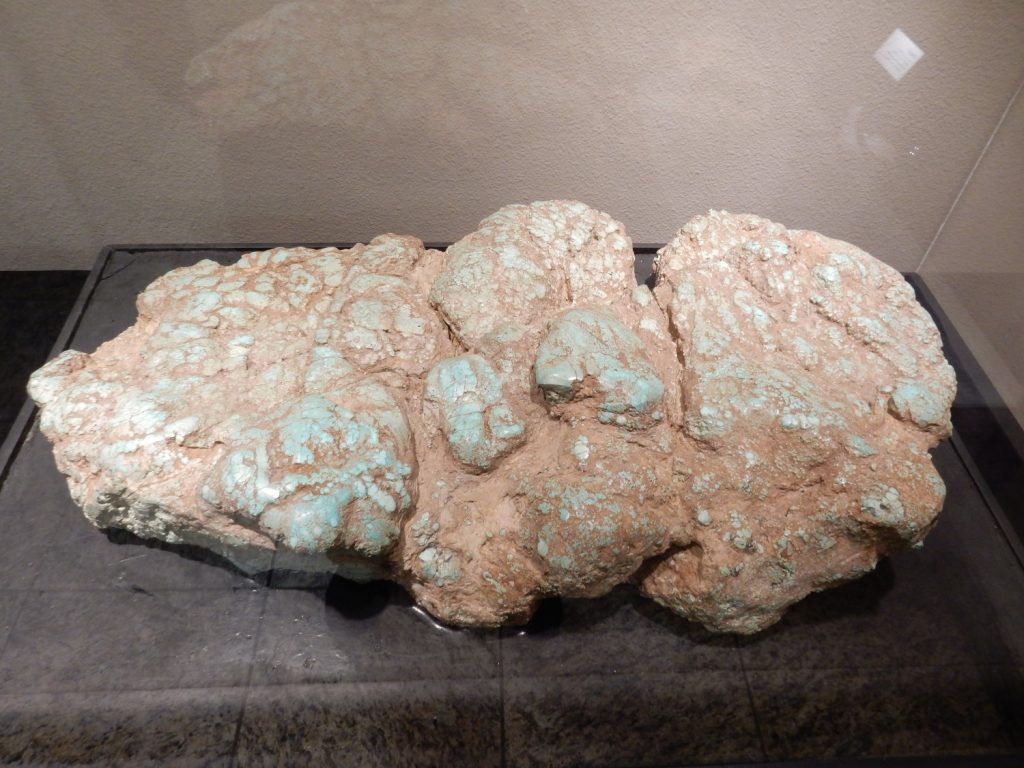

Turquoise.

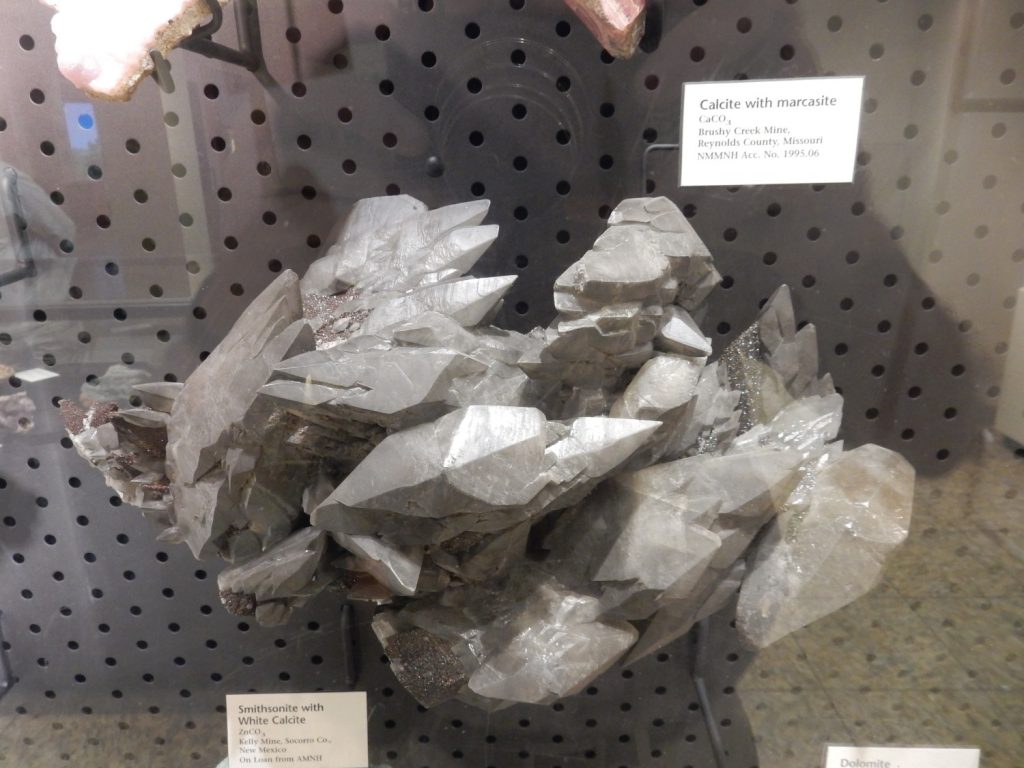

Some unusually well-crystallized calcite with markasite. Neither is particularly rare, except as such spectacular crystals.

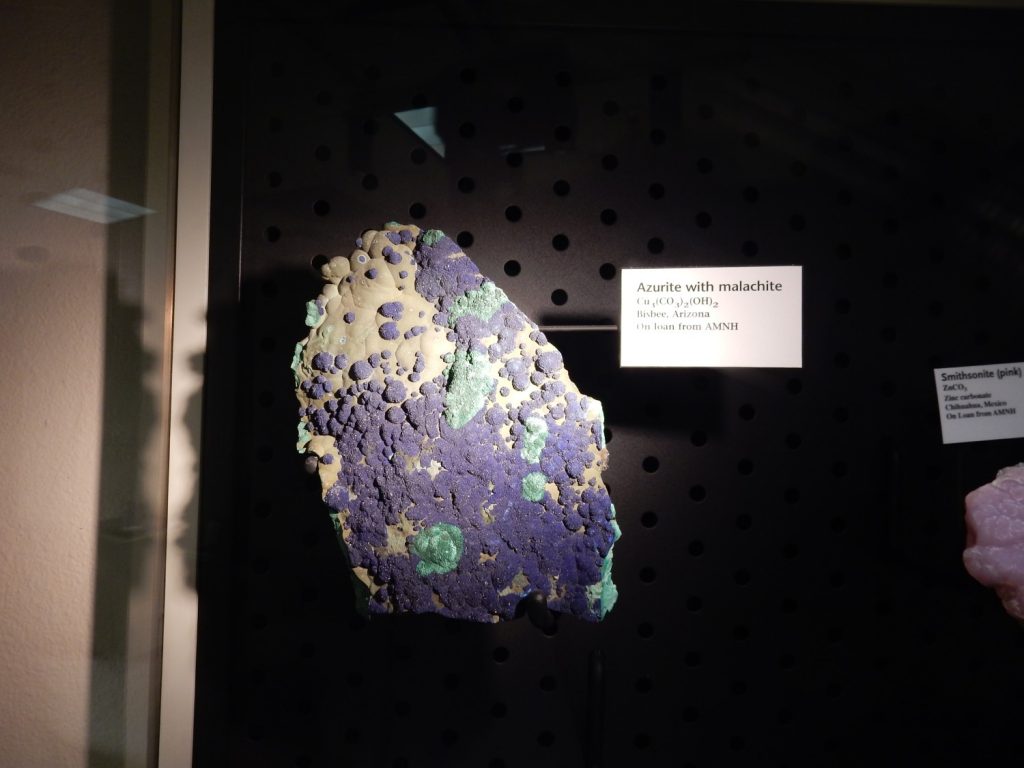

Azurite with malachite.

These are two of the three most common copper minerals at the Nacimiento Mine, along with chalcocite. I’ve never found anything this spectacular, though. Well, that’s why it’s quite literally a museum piece.

Citrine, an orange form of quartz crystal.

Yeah, flash. My only serious complaint about the museum was that the specimen lighting was not always optimum.

Gypsum.

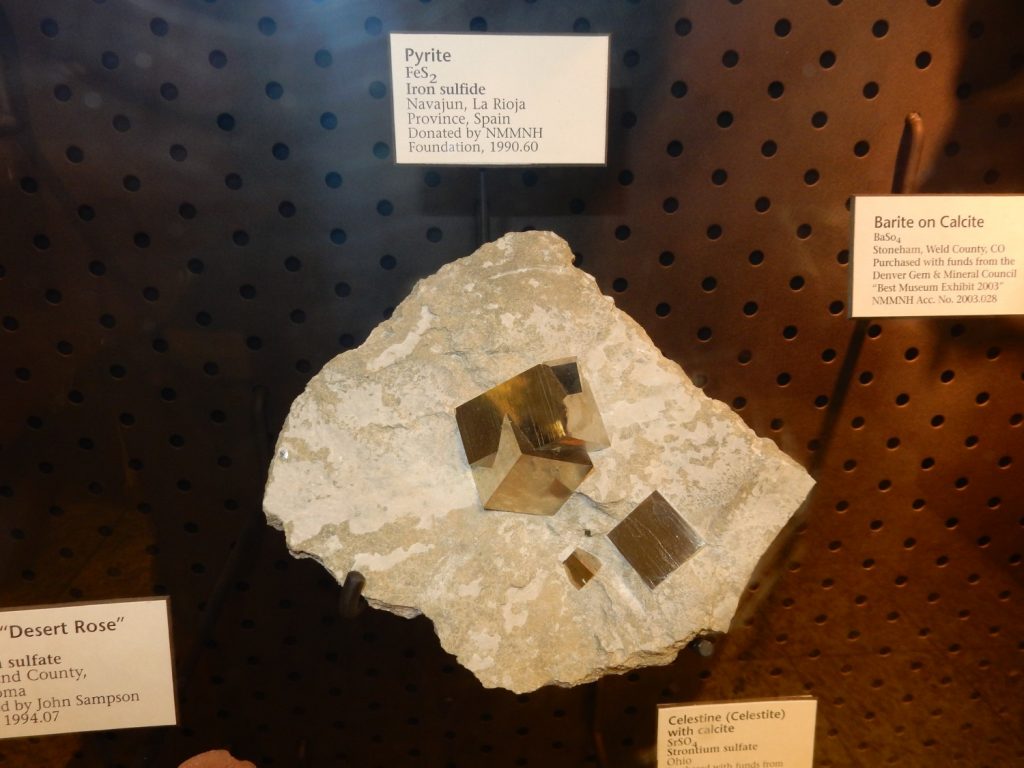

Some almost perfect pyrite cubes.

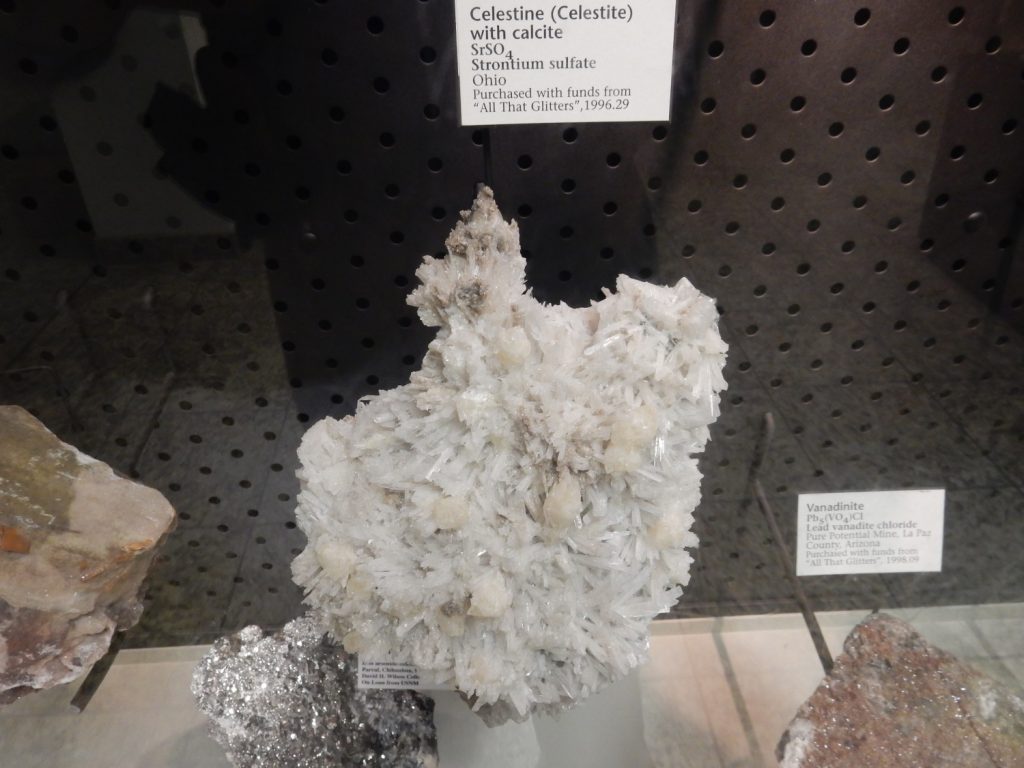

Celestine, an important ore of strontium.

Sulfur.

I think that’s enough of what my more cynical friend sometimes describe as “mineral porn.”

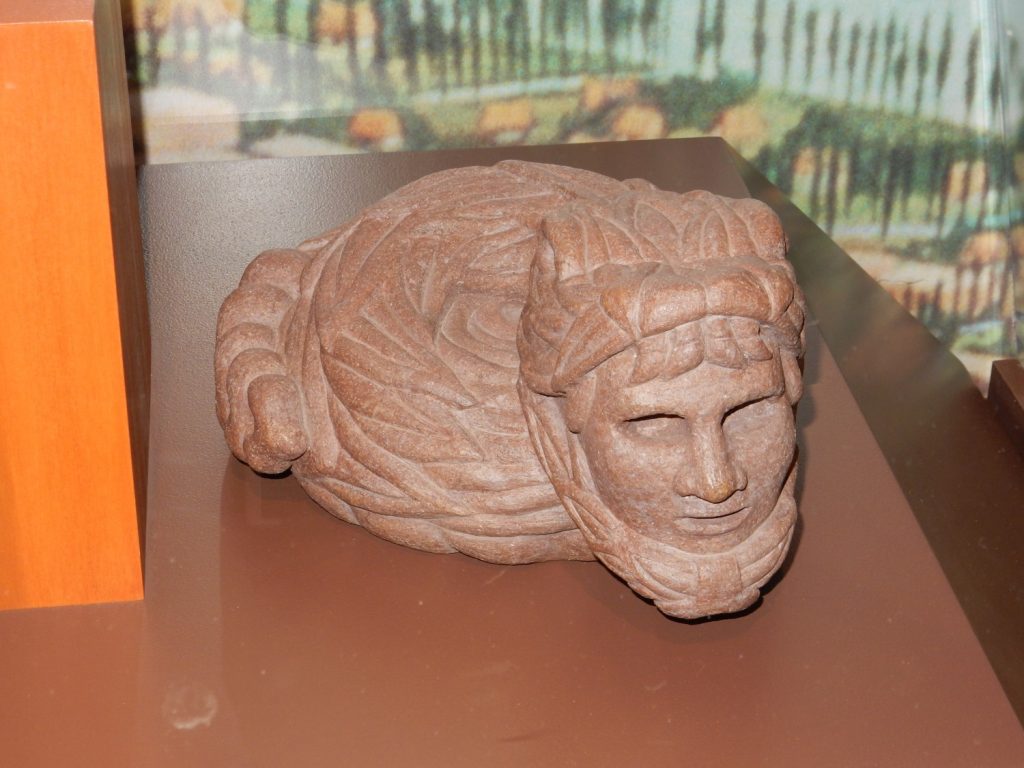

The Museum was having a special exhibit on chocolate. It was moderately informative, but I can’t say I was super-impressed. This chocolate snake god was worth a photo.

Another chocolate-related Mesoamerican diety:

Apparently the Aztec liked theirs bitter, spiced, and foamy, served in ritual cups. Europeans thought to add sugar, and then invented the chocolate bar, which I regard as yet another indication that God loves us and wants us to be happy.

More rocks, this time from the Solar System exhibit. An iron meteorite:

The crystal pattern is thought to have formed at high pressure with slow cooling, and is evidence that iron cores formed even in quite small planetesimals quite early in the history of the Solar System.

Lunar basalt.

Will not be adding to my collection soon: The Apollo Program brought back a total of about 850 pounds of moon rocks, and the program cost about $257 billion in today’s dollars. Granted the program did much more than just return moon rocks, but the brainless calculation puts the cost of this stuff at 300 million a pound.

Money well spent, though with the advances in robotics since, I wouldn’t support such an endeavor today.

It’s 1:00 and the group has arrived.

Patrick Rowe also came early, to deliver some unique and valuable fossil finds to the museum paleontologists. Congratulations to Pat for his contributions to science.

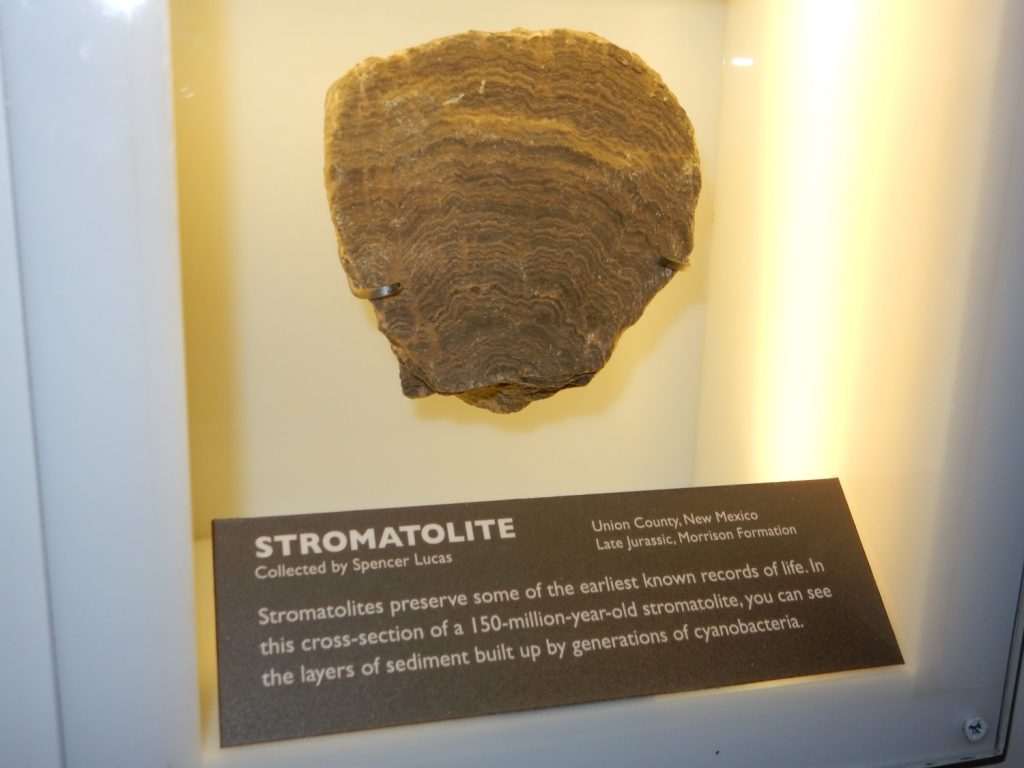

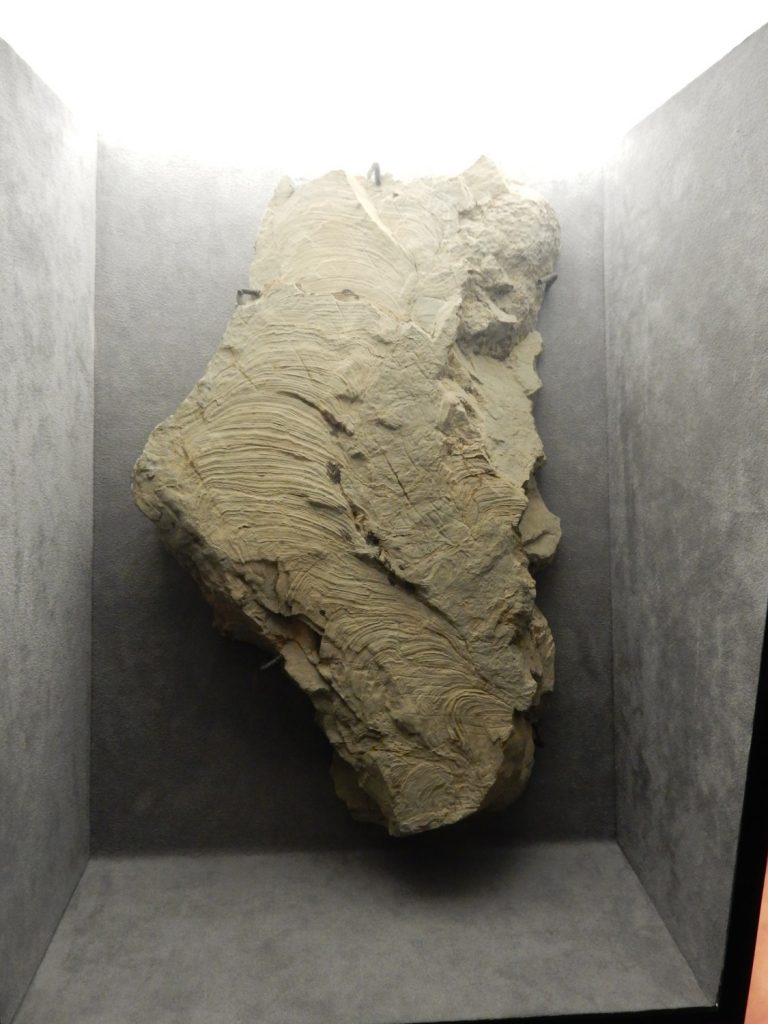

Our tour is a self-guided walk through geologic time. This begins with the first life in the Precambrian, preserved as stromatolites (algal mounds).

Though, oddly, this sample is actually Jurassic, not Precambrian. For illustrative purposes.

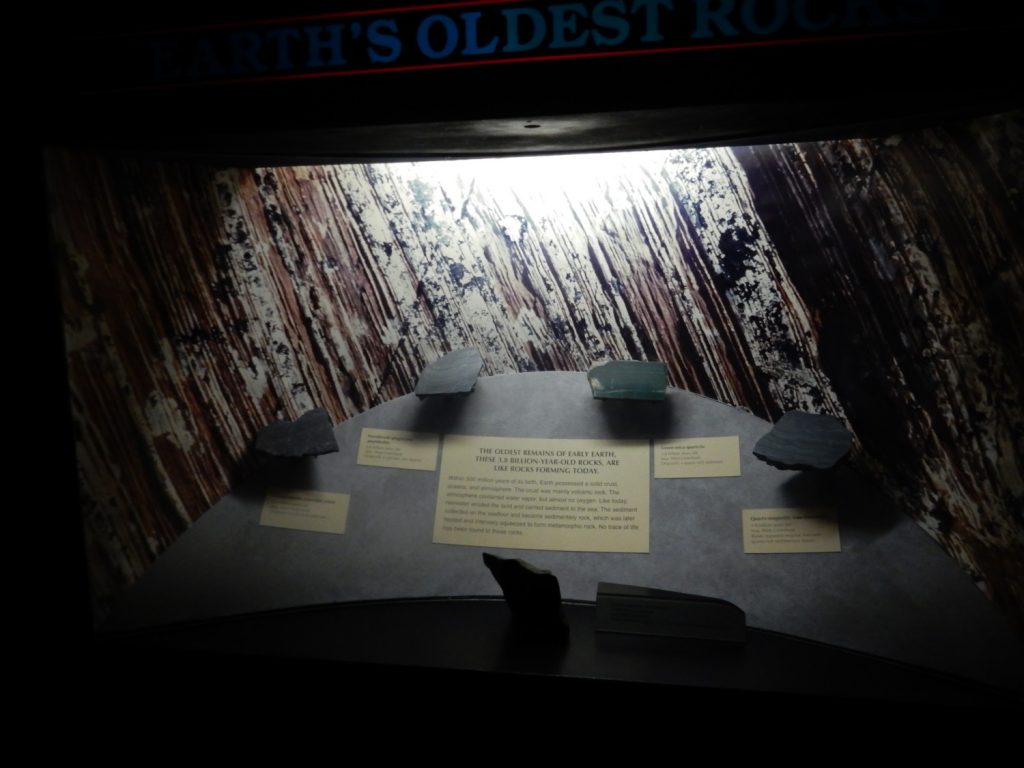

Samples of Acasta Gneiss, close to the oldest rock on Earth. (It has some competitors, and individual zircon grains have been found that are significantly older. Still.)

Stromatolite that is actually Precambrian — I think:

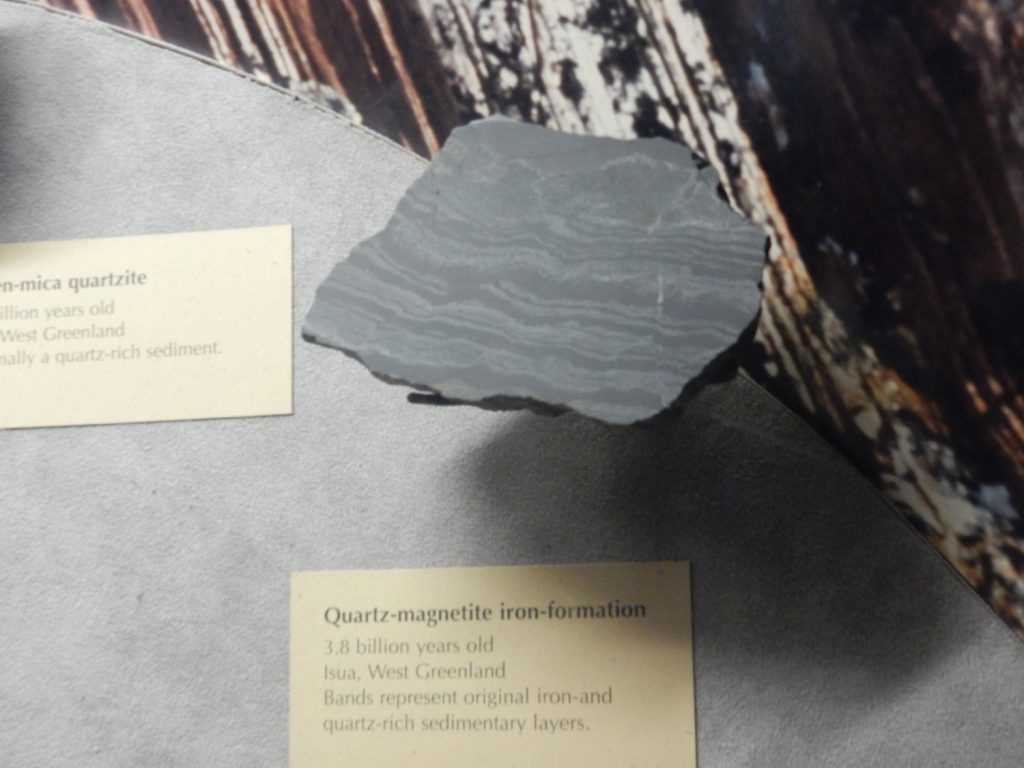

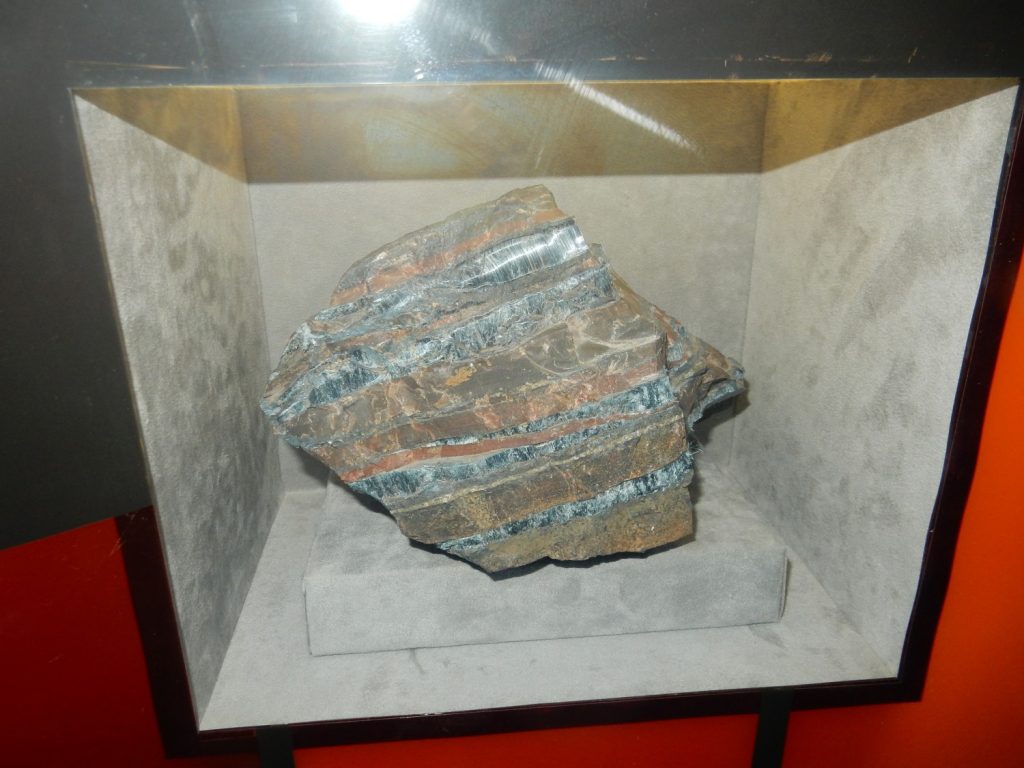

Classic banded iron formation.

Most of this stuff is from about 2.5 to 1.8 billion years ago, and it’s now the major source of iron ore. None has been formed in the last half million years. It’s thought to record oxygenation of the Earth’s atmosphere, though a lot of details are still being haggled over.

Another stromatolite.

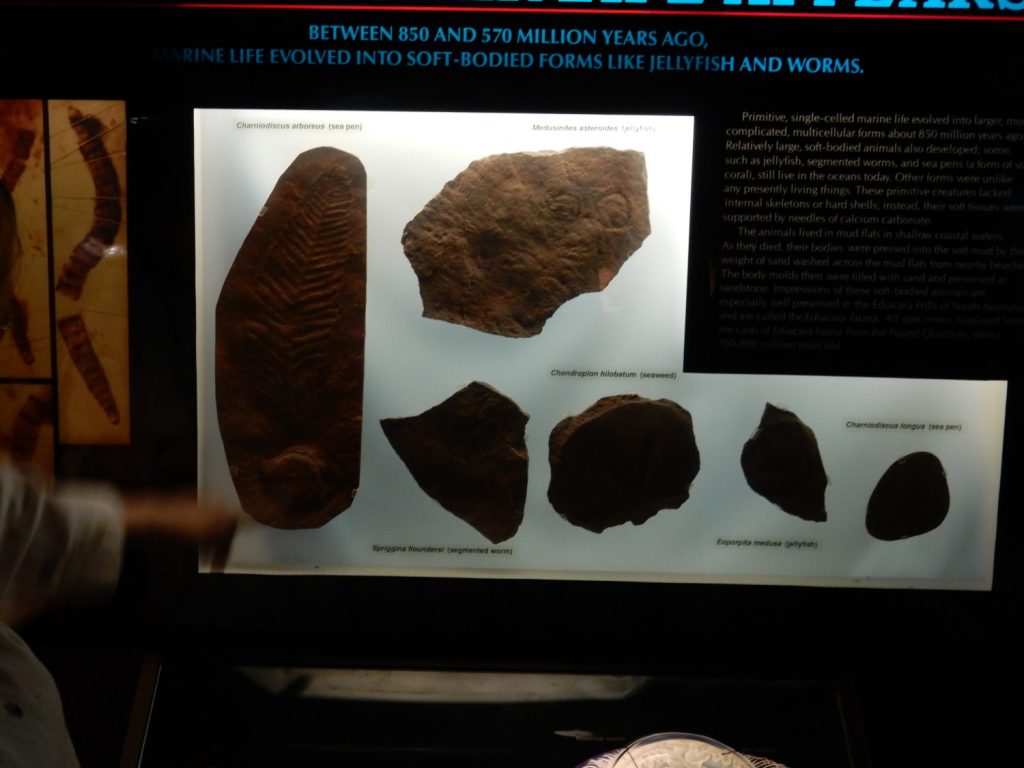

Ediacarian fossils.

The Ediacarian biota emerged at the very end of the Precambrian, and they’re a bit mysterious. The first organism may have been a sea pen, the second set jellyfish, and the last an algae. But the identification of the first two is uncertain, though it’s widely believed the Ediacarans included the first metazoa, or animal forms.

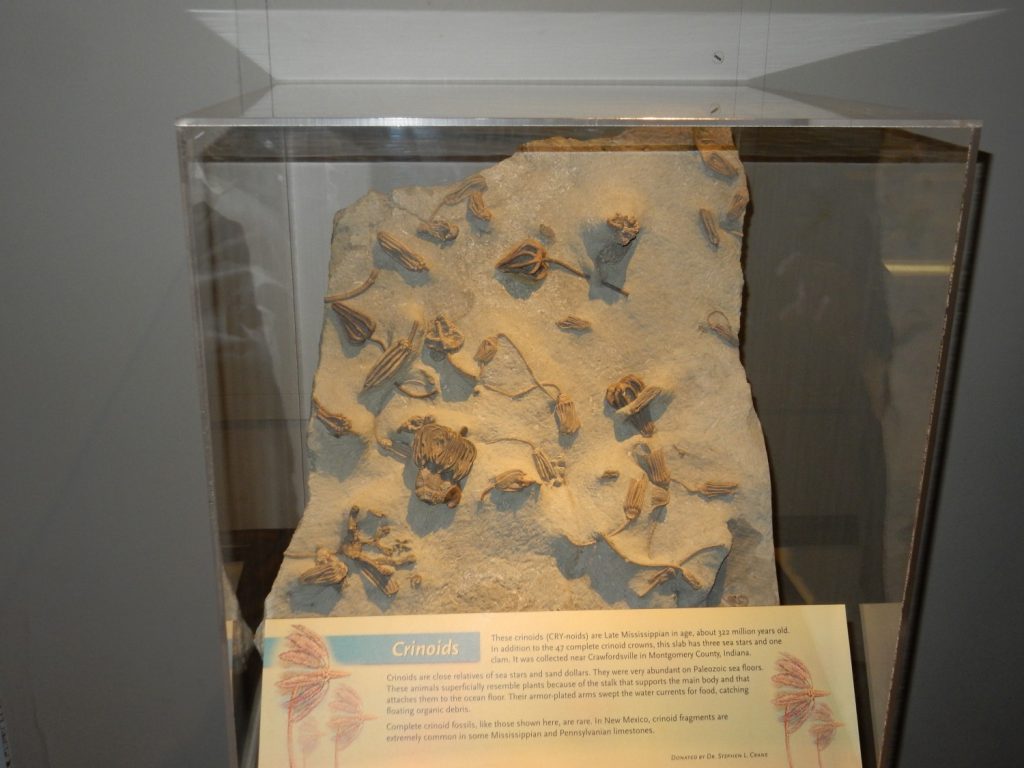

Carboniferous crinoid stems.

These are not only exquisitely well-preserved; the preparer did an excellent job on them. Preparation of samples is a skill I’m only just beginning to learn.

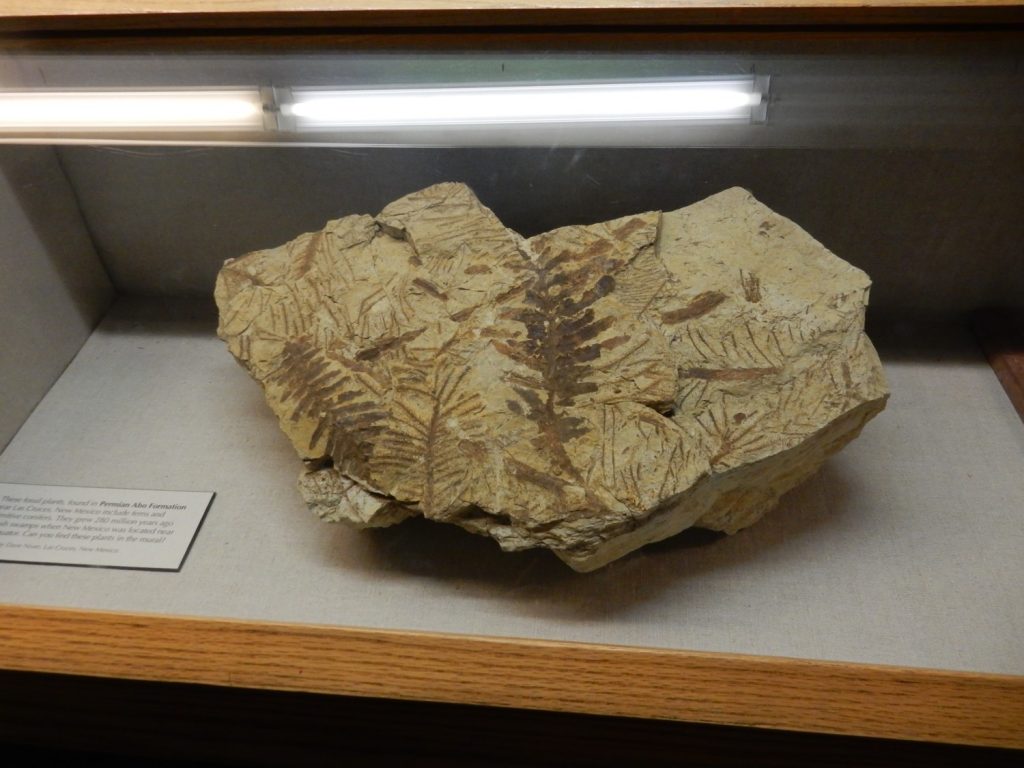

Leaf prints.

This is from the Permian Abo Formation, which is exposed in many locations across New Mexico.

The Museum had a tank with a live lungfish in it, a survivor of the Triassic. Alas, I couldn’t get a good photo of it with ambient light, and I wasn’t going to disturb it with a flash.

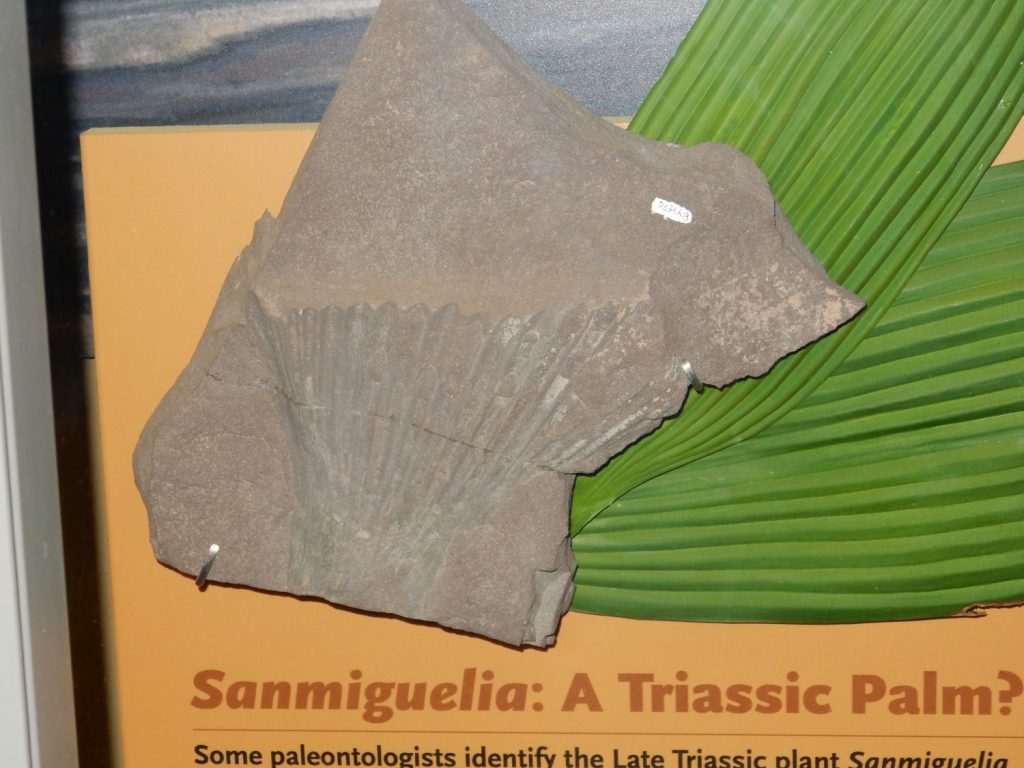

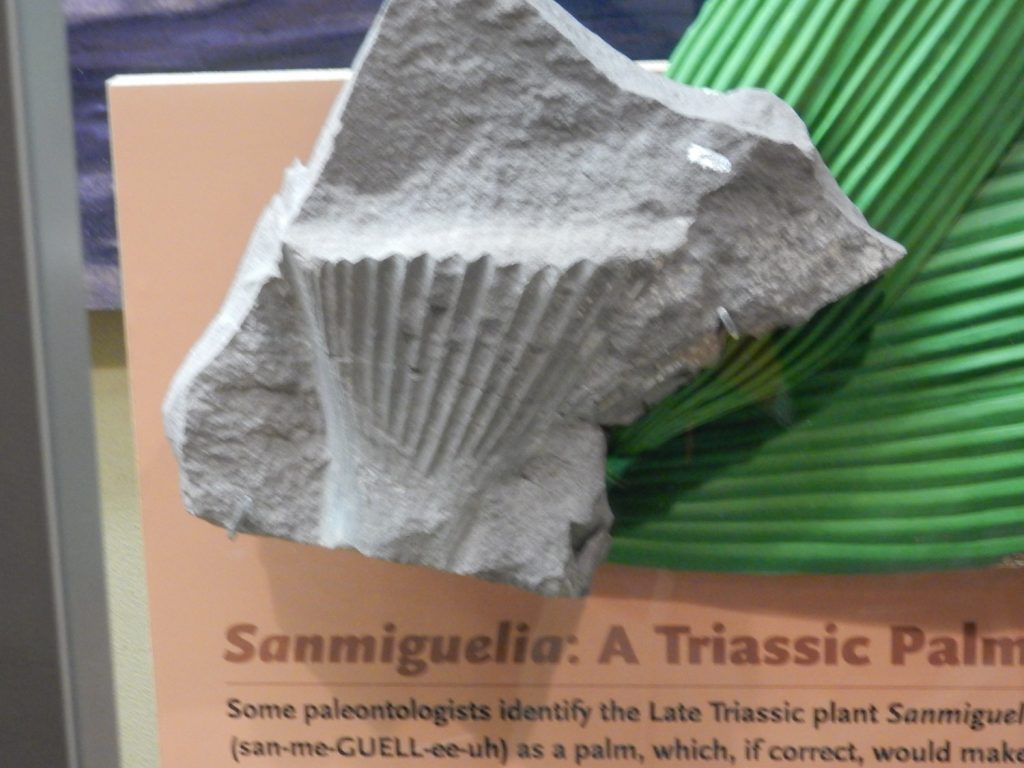

A Triassic palm.

Hmm. Light seems better this way:

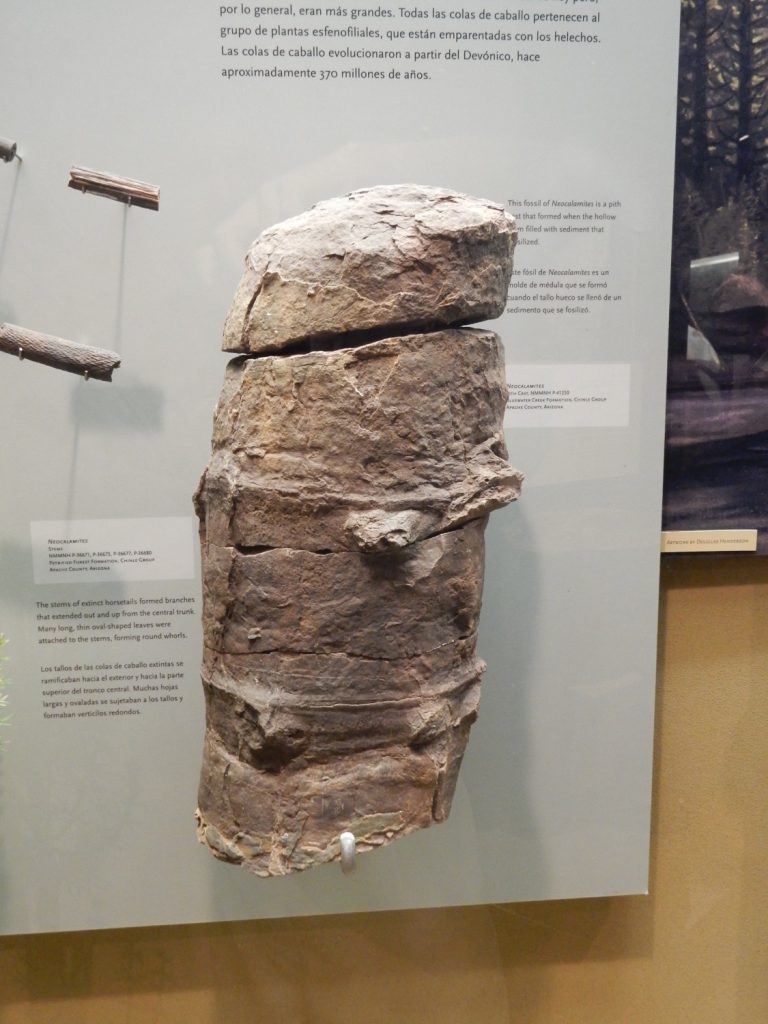

Lungfish burrow.

Early dinosaur fossil slab, from Ghost Ranch.

Various reptile scutes (bony back armor)

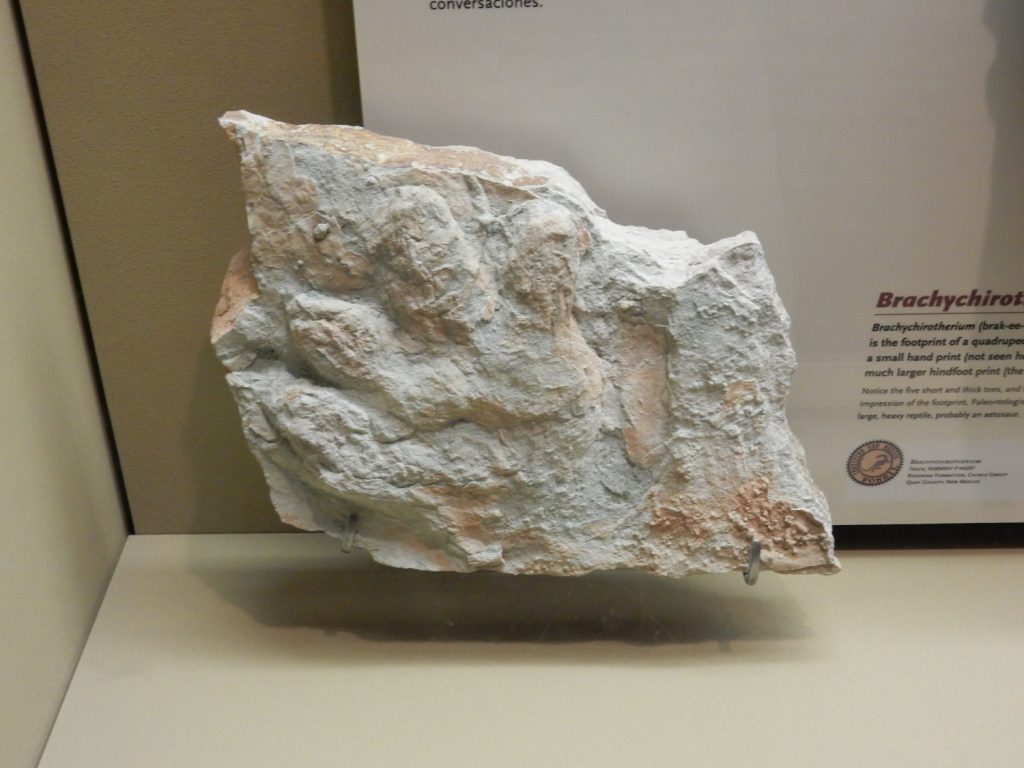

These kinds of reconstructions are always fun:

The critter at left is Placerias, a synapsid. The only living descendants of synapsids are mammals.

Nice to know who to root for in this encounter.

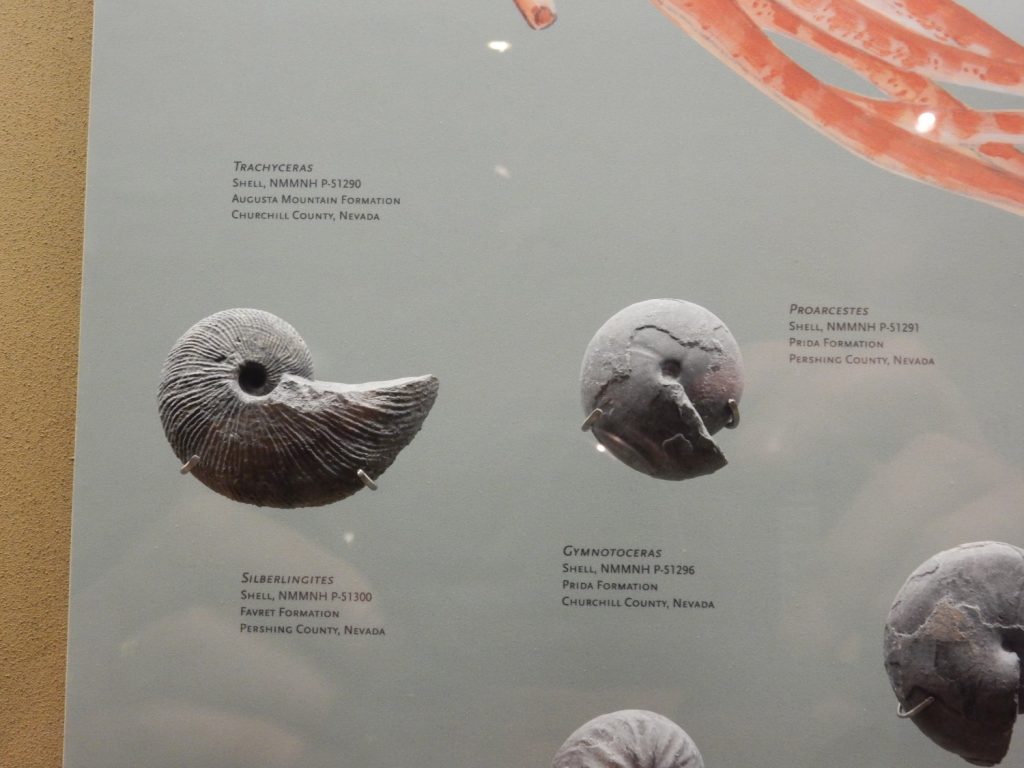

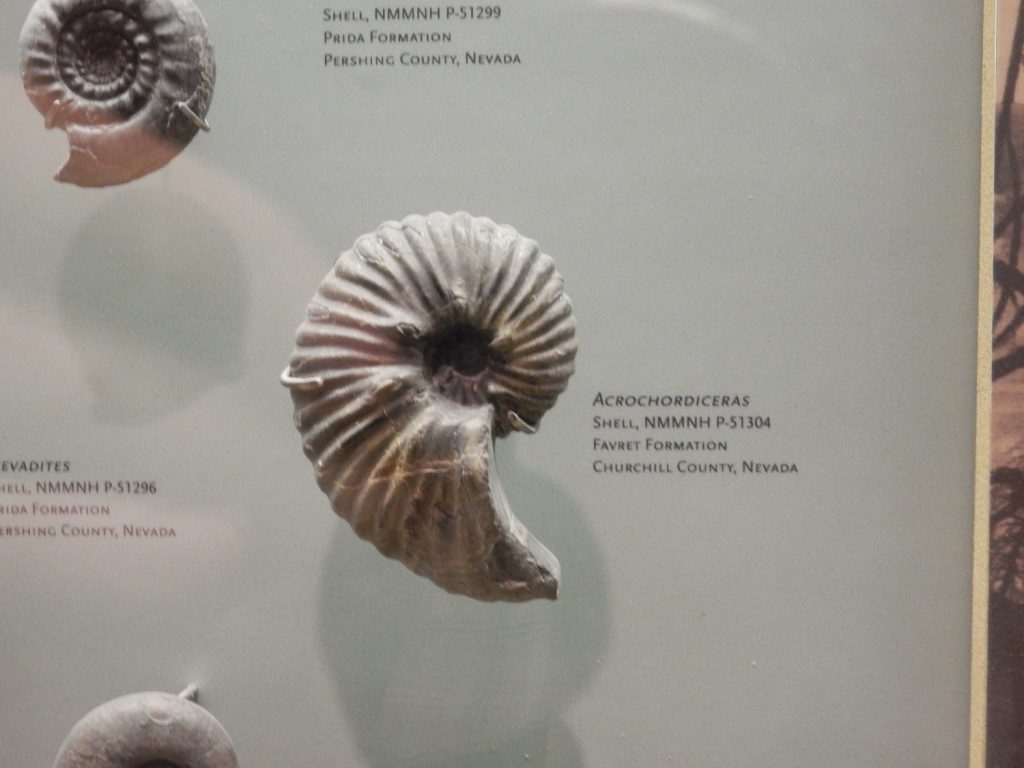

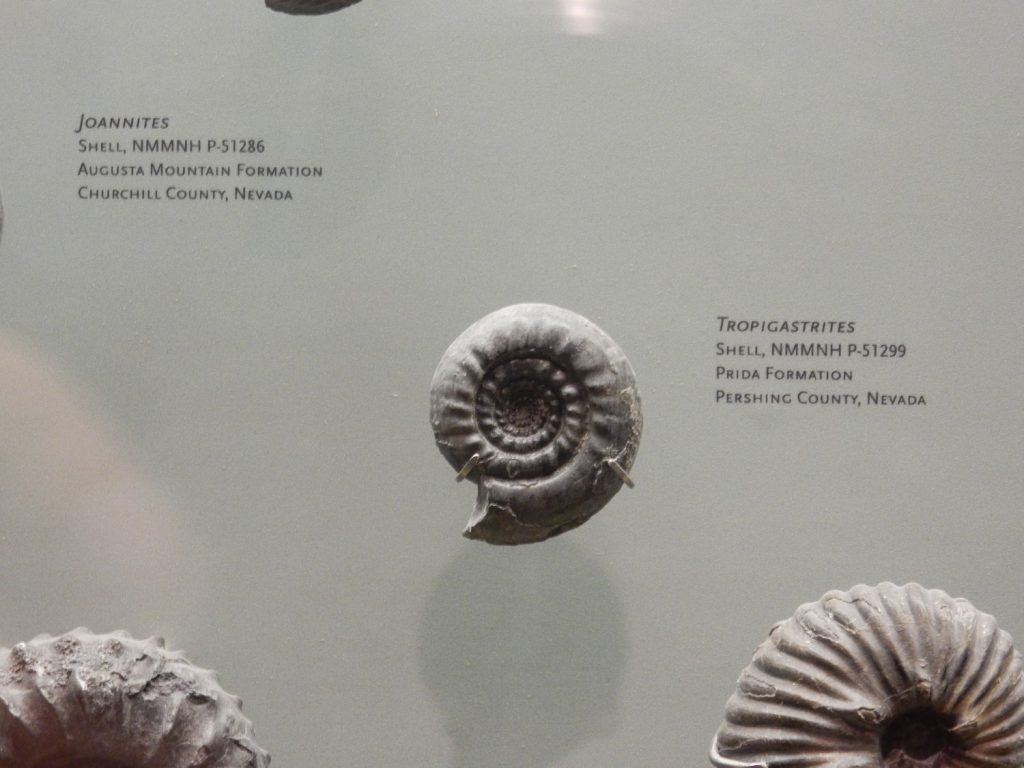

Ammonites”R”Us:

Ammonoids are great for dating Mesozoic rock beds, because they evolved so quickly. However, they did not survive the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction.

Individual specimens:

Brachiosaurus leg

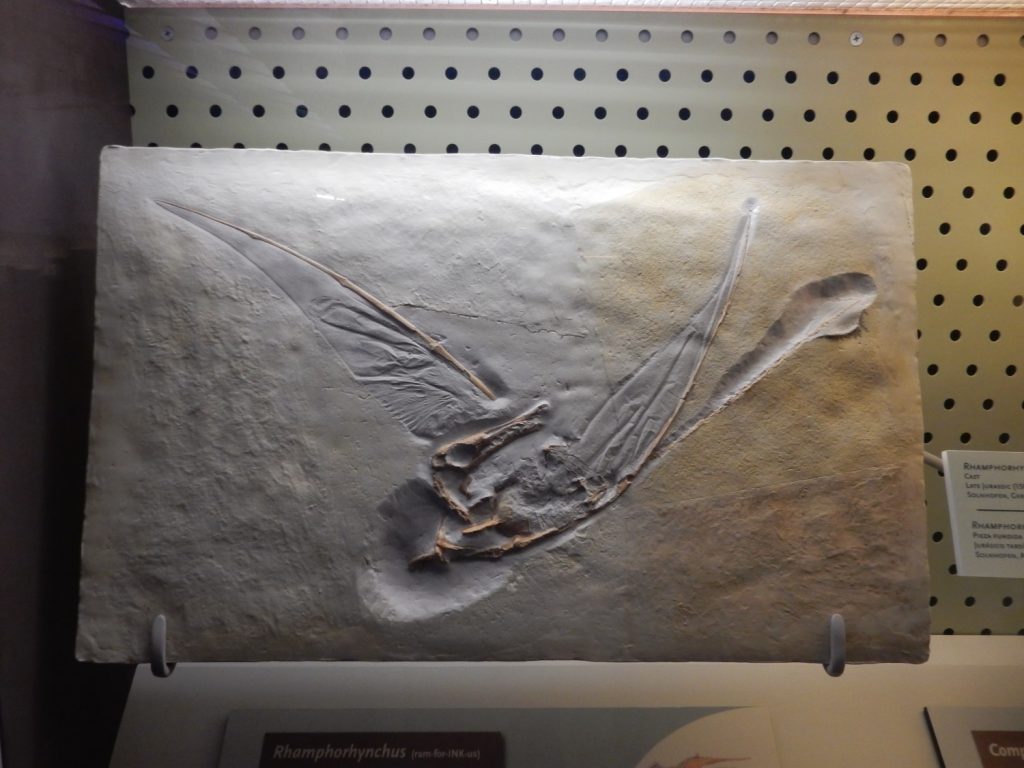

Early bird

Alas, no fossil worm.

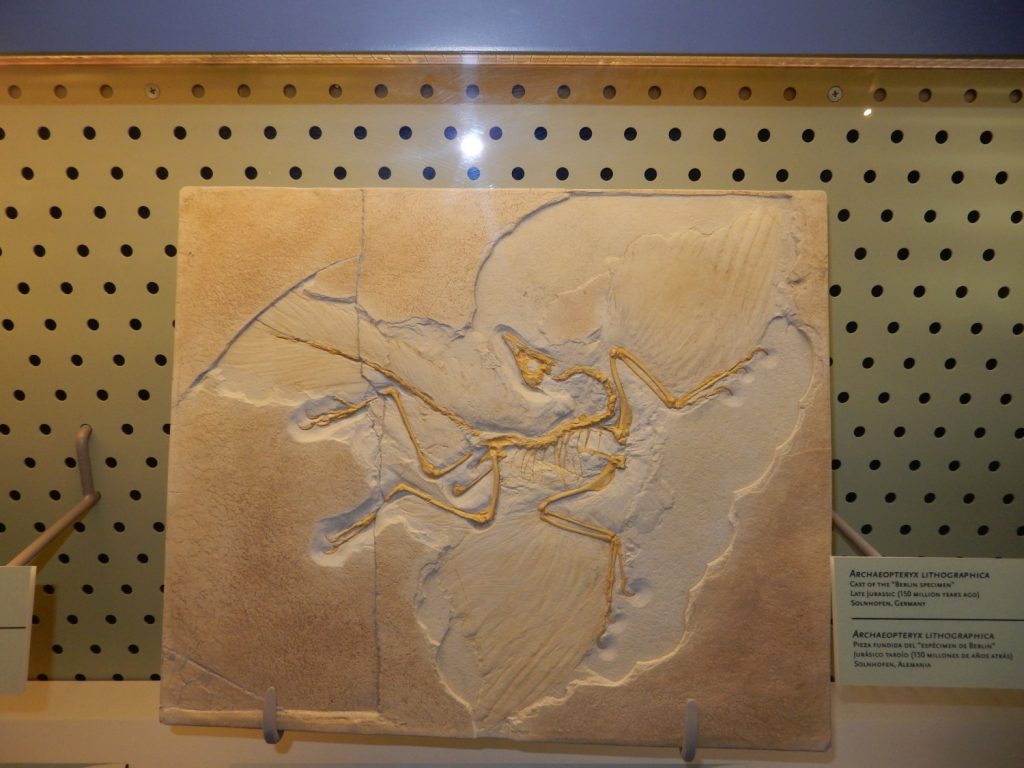

Cast of the classic Archaeopterix fossil.

We got kind of lost at this point; we did not see the directions from the Jurassic room to the Cretaceous room. After asking around, we found our way again.

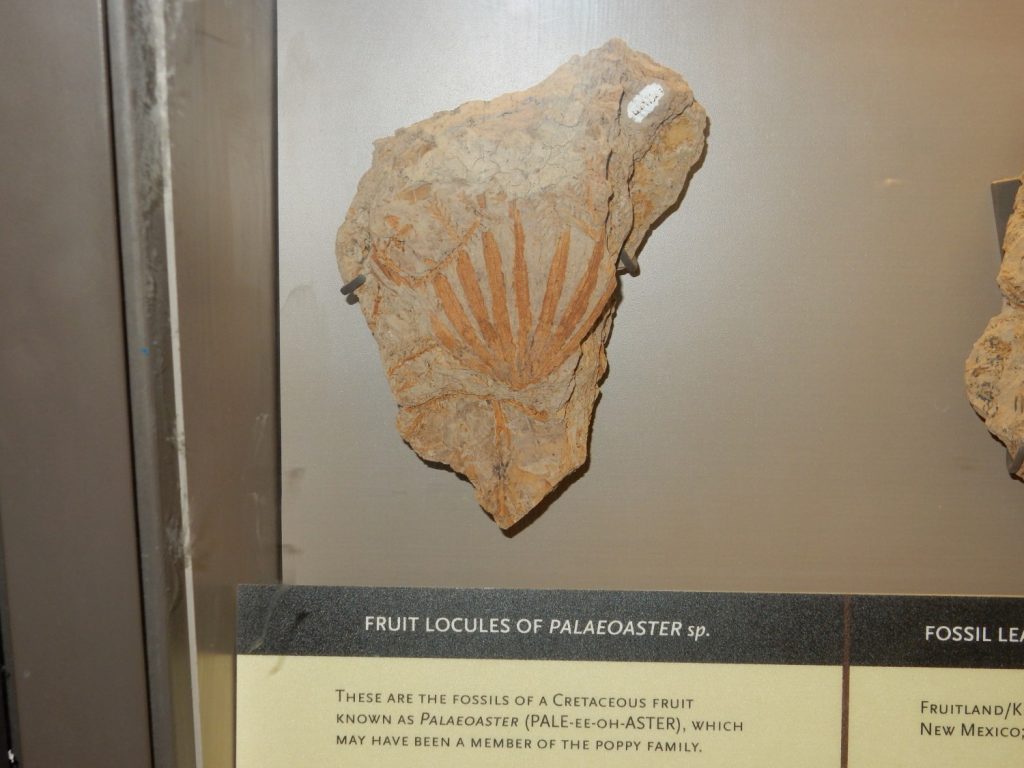

One of the earliest flowering plants.

This one I had a hard time getting a good photo of, because of skylights directly overhead.

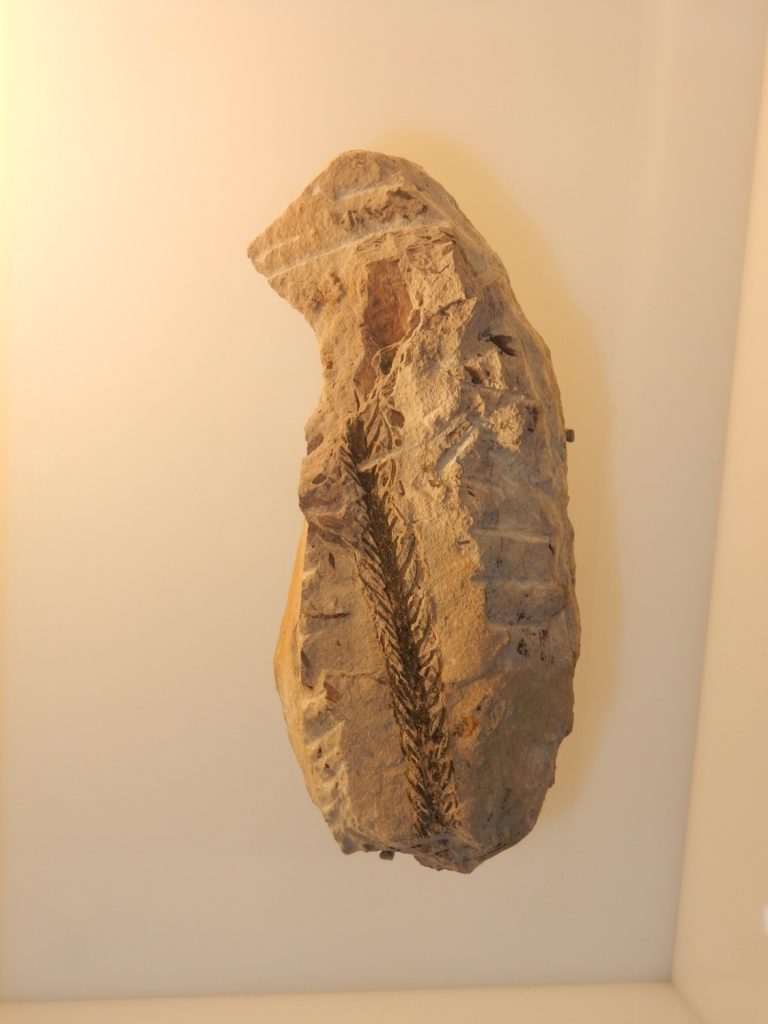

Cretaceous conifer.

Echinoids.

These come from the U-Bar Formation, which forms really impressive fossil reefs exposed in the bootheel of New Mexico. I’d love to visit, but it’s way out of the way.

Geologically young volcanic rocks, including some from the Jemez.

And then we were done.

Admission: $7, in part because I’m old. Well worth the cost.

The weather was quite wet as we left the museum. The monsoon has, in fact, come in with a bang this year, which is always welcome. It started the third week of June or thereabouts and we’ve gotten some inches of rain since then, with more forecast. This is very good news, but it does mean I won’t get much hiking in until the fall dry season. But that’s the best hiking season of the year, so look for some good posts then.

Meanwhile, some parts of the public lands have begun to reopen, and I’ll try to get some hiking in in dry intervals the next couple of months. Though I’d rather we didn’t have any.