Great American Eclipse wanderlust, day 2

Day 1 may be found here.

Being a male over 50, it’s almost inevitable that I’ll wake up in the wee hours of the morning, which are well named.

So on this particular morning, the second of my trip, the quarter Moon is bright overhead.

This photo is partly a test to see if there is any hope of capturing the eclipse on film on the big day. The eclipsed Sun is, after all, almost exactly the same size as the Moon. I’m not planning on wasting much precious eclipse time (just over 2 minutes) fussing with the camera, but I figure on attempting one shot.

Anyway, it’s fun to be at the start of the final week before the eclipse.

Breakfast in camp: Steel-cut oats (easily cooked over a small propane stove), bacon and eggs (more problematic; my new non-stick pan almost immediately overheats), bran cereal with electrocuted milk* and xylitol, and reduced-sugar cranberry raisins in the oats. Really not a bad way to wash down the morning pills: Metformin for the diabetes, Co-Q as a charm against the side effects of pravastatin, omeprazole for gastric reflux (my stomach is very slightly messed up from the diabetes), and a multivitamin as insurance against my restricted diet. Growing older … it is not for the wimps.

Devils Canyon Campground is located southeast of the Abajo Mountains. These are laccoliths, mountains produced by magma penetrating between sedimentary rock layers and pushing them upwards, almost like a blister in the skin of the Earth. The magma later cools to produce great domes of crystalline rock, surrounded by upwarped sedimentary beds. Like these:

These are almost certainly beds of the Cretaceous Dakota Formation. To the right is a crystalline dome, now exposed by erosion. I took the time some years back to drive into these mountains and grab a piece of them; it’s a very pretty diorite.

Diorite is a plutonic igneous rock with intermediate silica content and relatively low alkali content. What this means is that it’s mostly feldspar; more silica and it would show quartz, less and it would show lots of pyroxenes, and more alkali would mean feldspathoids. The needles are hornblende, and incorporate most of the iron and magnesium content of the rock.

The geology here is a lot like the geology around the Ortiz Mountains near Santa Fe. The ages are even similar; 25 million years ago for the Abajo intrusion versus 35 million for Ortiz, and Cretaceous beds in both locations (slightly younger beds, of the Mesaverde Group, in the Ortiz Mountains.)

I pack up and start north. The lighting seems very good for photography as I approach Moab from the south.

The weather is also much improved.

The mountains right of center are the La Sal Mountains, about the same age and character as the Abrujo Mountains. Further west are the Henry Mountains, and I expect to pass close by these on my return leg. I’ll ruminate on the origin of all these laccolith mountains then.

The low cliffs are likely Entrada Formation, here a fairly resistant sandstone. It’s the main formation the arches are carved out of in Arches National Park. In fact, as I continue north, I see a very nice amphitheater in this formation:

Just the place for a Gordon’s concert, hey? Alas …

I pass through Moab, which, as usual, is a madhouse of tourists. Yeah, I know what I am. I think we tourists are like grasshoppers: Not too bad in small numbers, but unbearable when we swarm. I’ll just have to live with that, since, for safety’s sake and Cindy’s peace of mind, and since I’m traveling alone, I’m going to be mostly sticking to places with lots of tourists.

Near the turnoff to Canyonlands, Island in the Sky section:

This is a nice exposure of several of the formations in Canyonlands. The massive sandstone cliffs near the top of the mesa are late Triassic-early Jurassic Wingate Sandstone. There are some thin beds of Kayenta Formation on top of the mesa, not terribly visible from here. Under the Wingate Sandstone is the Triassic Chinle Formation, which here consists of greenish-gray reduced beds below dark sandstone and mudstone beds.

Reduced beds: These had enough organic matter in them, and were deposited under stagnant enough conditions, that iron in the rock was reduced from insoluble red ferric iron to soluble ferrous iron. This either reacted with other components of the rock to form greenish minerals or was leached away.

Beneath the greenish-gray Chinle beds are dark red beds of the Moenkopi Formation, also Triassic in age. I saw this yesterday at Natural Bridges National Monument, where it is a more characteristic chocolate brown. This is a very extensive formation; like the Chinle, it is found throughout the Colorado Plateau and is present back home in the Jemez. However, the Chinle back home is prominent enough to be promoted to group status, while the Moenkopi is a thin (but very distinctive) brown bed found only in the southwestern Jemez. I made a point of hiking to an exposure of it once.

The whole Colorado Plateau is an unusually stable block of crust that has been slowly subsiding, with occasional pauses, for the last three hundred million years. (Six hundred million for the southernmost portion, near Grand Canyon.) This means that sediments have been slowly accumulating on the Plateau for all that time, building up a record of the geologic history of western North America. Just in the last few tens of millions of years, the entire western United States has been uplifted by hot mantle rock as it has drifted over the East Pacific Rise, and the Plateau has been deeply eroded by canyons that expose this extensive rock record. It’s a real geologist’s playground.

The Chinle Formation records the rise and erosion of the Uncompahgre Uplift, a range of mountains thrown up over 300 million years ago when North America collided with Africa and raised mountains all over the current location of the Rocky Mountains. These ancient mountains are known, logically enough, as the ancestral Rocky Mountains. The Uncompahgre Uplift reached clear into the Espanola area, which is why some of the formations formed from sediments eroded off these mountains reach from Utah to the Jemez. These mountains were eroded flat by the beginning of the Cretaceous, when the birth of the Sierra Nevada to the west tilted down the continent and allowed the sea to invade the entire area of today’s Basin and Range, Rocky Mountains, and High Plains to produce the Western Interior Seaway.

Also notice the waning moon in the photograph. Less than a week to go!

Helpful hints for tourists:

You may laugh (I admit I cracked a smile) but toilets are used very differently in some perfectly modern and civilized Asian cultures. Shoot, I’ll redfacedly admit that I was puzzled the first time I traveled to Europe and encountered a bidet …

Island in the Sky is very nearly a true island in the sky, surrounded by escarpments on all sides except a narrow ribbon of road from the north. It does not, however, have the ecological isolation of a true island in the sky, nor is it distant from areas of similar or greater elevation. True islands in the sky are quite rare, the most outstanding examples being the tepui of South America.

Buckman Mesa is the nearest thing to an island in the sky in our area. It’s not ecologically isolated or distant from similar terrain, but it does have some of the feel. Johnson Mesa near Raton definitely has the feel of an island in the sky, but the escarpment is not steep enough for true ecological isolation.

And I love islands in the sky, which is why I keep ranting about them.

Anyway, I got to the first good viewpoint for a panorama and got out my tripod.

Incidentally, the panoramas here may all be clicked on for a full-sized version, and I recommend trying it. Panoramas look distorted on this small scale, but at full scale, it’s almost like being there.

I decide to have some fun with my telephoto setting.

I believe this is Candlestick Tower, for which this overlook is named. The top is Kayenta Formation, then massive beds of Wingate Formation, then Chinle and Moenkopi Formation beneath — the Chinle forming the more gentle slopes and the Moenkopi forming the flat ground at the base of the tower. Same formations I just saw at the park entrance.

Cleopatra’s Chair:

This is a knob of Navajo Sandstone, the next formation above the Kayenta Formation. The white rim in the foreground is underlain by the White Rim Sandstone, a Permian formation nearly the same age as the Cedar Mesa Formation I saw yesterday at Natural Bridges National Monument.

As I’m leaving, a British gentleman about my age is arriving with his own camera and tripod. I like the British; I’m partially of English ancestry myself, the rest being southern Scandinavian with a touch of Scottish, and the similarity in culture is enough to make the differences entertaining. I also like the dry British sense of humor very much. He comments that it’s a good thing we no longer live in a day of expensive chemical film. I can only agree … but I’m already running low on one battery pack for my camera. It takes lithium batteries, which are too expensive to buy in large numbers and require recharging. The old camera had many faults, but its sole advantage over the new one (aside from not crying much if I accidentally drop it off a cliff) is that I can simply keep feeding it alkaline disposable batteries as needed.

Another panorama, from the Orange Cliffs Overlook.

Not too different from the previous, except that Eccles Butte is a little more prominent in the middle distance at left.

I arrive at the Grand View Point, which gives you a grand view to the south. I slap on some more sunscreen, park my hat on my head, load up and don my pack, and grab my walking stick. The area is swarming with tourists. And it is here that I have my cougar encounter, not ten yards away. Lean. Hungry-looking. Dressed in hot pink. She sizes me up at a glance as too old and gamy and moves on.

I thought I had my tripod leveled, but this panorama took some work to come out right.

Worth the effort. The whole lower plateau here is underlain by White Rim Sandstone. Beneath this are red beds of the Organ Rock Shale. Not easily visible from here is the Cedar Mesa Formation, the same formation I saw yesterday at Natural Bridges National Monument, which lies beneath the Organ Rock Shale and is exposed in some canyon bottoms. The Organ Rock Shale pinches out further south, which is why I did not see it there. The White Rim is so like the Cedar Mesa that they are effectively indistinguishable around Natural Bridges, where there’s no Organ Rock Shale separating them, and it’s all mapped as Cedar Mesa Sandstone.

“Pinches out”: Sedimentary formations are deposited in a basin or set of basins where the sediments can be preserved long enough to indurate (harden into rock.) At the edges of the basin, the beds thin out to a knife edge and disappear — “pinching out.”

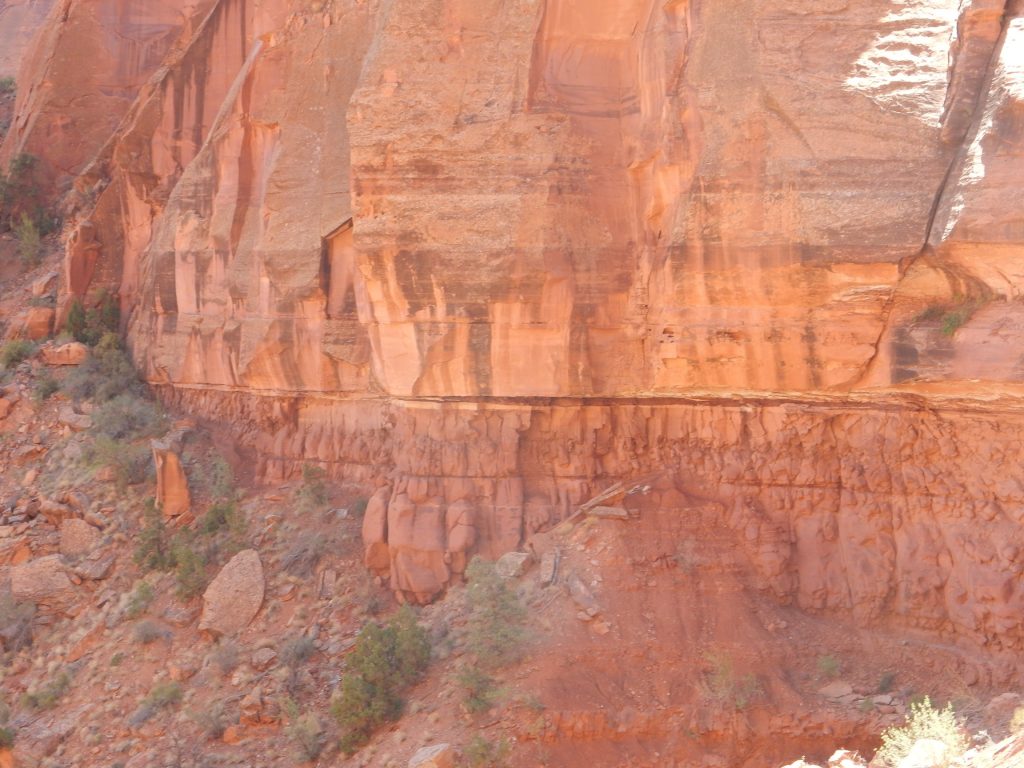

A closer look at this lower canyon.

Yes, that’s a dirt road on the right side of the canyon. The White Rim Trail. It’s actually a jeep trail. You can take a jeep down it with a back country permit. It takes about two days to drive the 100 miles of the trail at a reasonable speed; would make quite an adventure someday, given the right travel companions. Perhaps my friends Jeremy Conlin or Steve Harris might consider taking their sons with me some summer. Would be fun in Babe the Big Blue Box (Jeremy’s four-wheeler).

There’s a trail to the southern point of the mesa, and I need the exercise. It’s thronged with tourists, so I should be safe enough.

That’s Junction Butte at left. It’s the usual cap of Kayenta Formation over Wingate Formation over Chinle over Moenkopi, the latter forming the beautiful lower chocolate slopes.

This is a good time to note that the lowermost Chinle Formation is rich in sand and gravel, and this layer has been formally designated as the Shinarump Member. In the Jemez, where the Chinle is promoted to group status, the Shinarump is a formation in its own right, and a very substantial and important one. It’s very thick in our area, perhaps because the ancient Chinle River passed just north of what is now the Jemez, and it often contains petrified wood. In places, this has been replaced by copper minerals, and so we have the famous sedimentary copper deposits of our area, mined from the days of the Spanish conquistadores almost to the present.

You can see the Shinarump here as a thin lighter layer separating the deep red Chinle from the chocolate brown Moenkopi.

A closer view:

I proceed down the trail. My fellow locusts tourists are an interesting group. I note that German tourists are very numerous; I’m guessing it’s their traditional vacation season. Also a number of French tourists, a few Asian tourists, and some American families and a lot of what look like college kids.

The concretions, I mean. They’re not pebbles. Bruce, any ideas? This is Kayenta Formation, so earliest Jurassic fluvial environment.

Soft-sediment deformation, I’m guessing:

Meaning, something stirred up the beds after they were deposited but before they could harden into the hard rock seen here.

National park, so please to not take samples for analysis. But this could be a record of a volcano, gone extinct 180 million years ago.

The trail ahead, with other tourists.

The knoll at the end of the mesa, festooned with tourists.

180-million-year-old sneaker tread.

No, not really. But dunno what it is.

I reach the tip of the mesa, set down my pack, take out a water bottle and chug it down, and set up my tripod for a 360:

The Colorado River far to the west.

South (into the sun, alas):

Candlestick Tower again:

The Needles District. I went here last trip, for the first time, but not right down into the needles themselves. Gotta save something for the future, since trips to Utah are a regular occurrence (lots of family).

I pull out my lunch. The chipmunks in the area take an immediate interest.

Then back to the trail head.

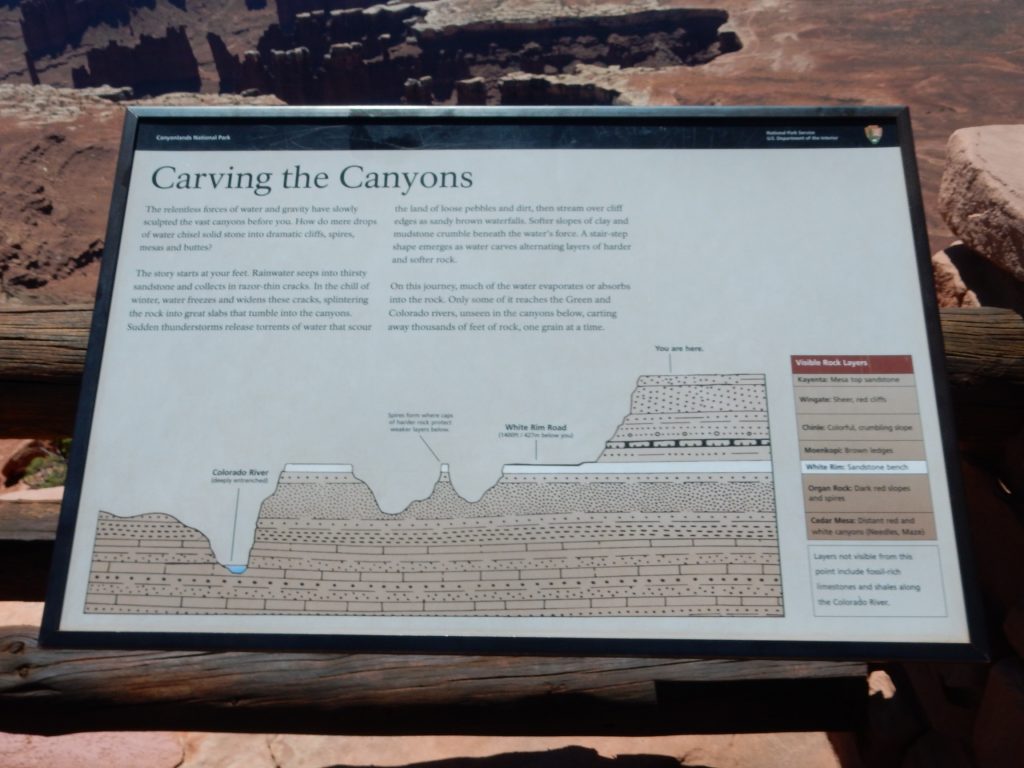

Signage, basically telling you what I’ve already told you, but with less snark:

I did find this useful for checking that I had got a couple of details right.

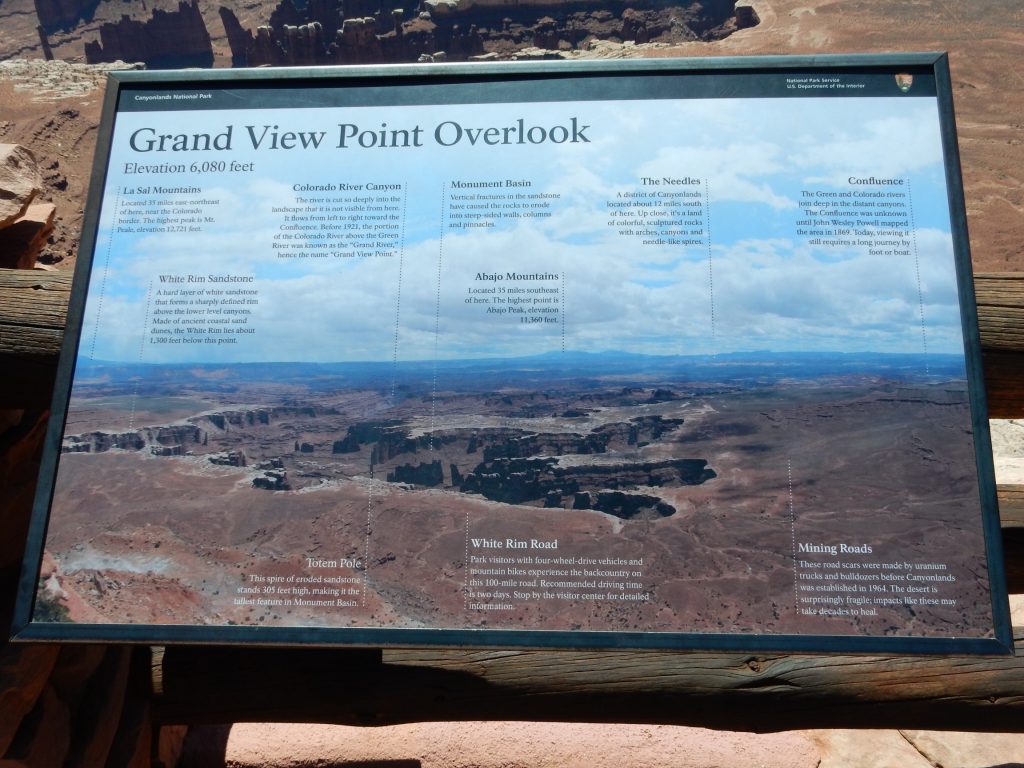

More signage.

So it’s called Junction Butte because it’s near the confluence of the Colorado and Green Rivers.

I stop in at the headquarters and ask a ranger about the Schafer Trail, which seems to descend through several formations. Turns out it’s a jeep trail joining the White Rim Trail. The weather has been good; he opines that I can probably do the first set of switchbacks and the straightaway below them safely in the Wandermobile. Time is short, but I decide to drive down a few switchbacks and see what I see.

It turns out to be a quite good gravel road, better than many I’ve dared in the Jemez.

A particularly good exposure of the contact between the Kayenta Formation and the underlying Wingate Formation.

The transition from the massive light Wingate Formation to the more thinly bedded and reddish Kayenta is quite clean and abrupt here.

More Wingate Formation along the road.

The occasional car passes me going the other way. There’s a fair amount of traffic on this road, considering. The road is wide enough for two vehicles to pass each other in reasonable comfort.

Peeking into Schafer Canyon.

My first good look at the switchbacks.

Let me say something about fear. Fear is a very good emotion, when it’s at the right level: Enough to keep you from being stupid, but not so much that it makes you stupid. At this point, with an excellent, well-maintained gravel road in fine weather, and occasional vehicles coming the other way, it is stupid to be afraid.

So far.

The geology here is Navajo Sandstone on the rim, a fairly thick section of Kayenta Formation beneath, and Wingate sandstone below that, exposed at lower left.

Again: Navajo Sandstone as the white, massive rock on the canyon top, then thinly bedded reddish Kayenta Formation, then massive cliffs of Wingate Formation. The slopes beneath are Chinle Formation giving way to Moenkopi further down. The contacts here are obscured somewhat by colluvium (geologist-speak for “dirt” when it falls from higher up).

That’s really an impressive set of switchbacks.

I work my way down these. Alas, it’s already well into the afternoon and I need to be in Provo by a reasonable hour. The trick is finding a good spot to turn around. There’s a small pullout at one point and I decide it will have to do. This is the only part of the drive that makes me very nervous. I get turned around safely and start back up.

A parting shot. (With my GPS lock distorted by the deep canyon.)

A couple more shots on the way out. The very sharp contact between the Wingate and the underlying Chinle:

A rare shale bed in the Kayenta Formation.

These show that the Kayenta was laid down in a fluvial environment — sluggish streams crossing flat terrain. This marks a geologically brief wet spell between the dry periods that produced the dune fields of the preceding Wingate and following Navajo Formations. It also makes the Kayenta a relatively weak formation, more susceptible to erosion — shale, being full of clay minerals, rarely indurates well.

Back on the blacktop, and more Kayenta Formation.

I head north. There is a prominent anticline here, the northern end of the Salt Valley anticline, that I want to photograph. It’s a classic example of an upwarp in the earth’s crust, caused in this case by rising walls of salt deep underground.

This is the west side of the anticline, where rock beds are dipping into the ground to the west. The nearest beds are Cretaceous Dakota Formation and Mancos Formation, but most of it is Salt Wash Member of the Jurassic Morrison Formation. This was laid down around 150 million years ago in a semiarid mud flat environment.

Further up the road, we look almost directly down the axis of the anticline.

You can see the beds curving up at left, eroded away along the center, and curving down again to the right. And, yes, a downwarp in the Earth’s crust is called a syncline.

Ahead are the Cretaceous Book Cliffs.

This is the south edge of the Uinta Basin. And “basin” here means in the geologic sense: A structural basin, where the crust once sagged slightly and accumulated sediments. Topographically, it’s now a high plateau. The cliffs are capped with Castlegate Formation on top of Blackhawk Formation. The latter contains coal; I’ll see more of it shortly.

Fill up with gas in Green River. Head north along that tedious stretch towards Price, with seemingly never-ending Book Cliffs to the east, San Rafael Reef to the west, and boring brown Mancos Shale between. However, this road cut catches my eye.

Road cuts: Geologists are in love with the things, because they provide such nice exposures of the rock beds.

If I’m reading my map right, this is pediment gravel atop the Blue Gate Member of the Mancos Shale. That looks about right. The lower bed certainly looks like Mancos Formation, and the top is the kind of gravel you get in pediments. Pediments: These are flat surfaces eroded at the foot of a steep escarpment in arid climates, often covered with a veneer of gravel from the eroding escarpment. This is certainly an arid climate, and the Book Cliffs are certainly a steep escarpment.

Through Price and approaching Castle Gate.

The upper part is Blackhawk Formation. If I’m reading my map right, The prominent sandstone bed halfway down is the Star Point Sandstone, and everything beneath is Mancos Formation.

A better view of the Star Point Sandstone up the canyon.

Well, maybe. The map shows Castlegate Formation at the top of the mountain and Blackhawk Formation beneath.

There’s a road cut right through a thick section of Blackhawk Formation exposing coal seams.

These seams are too thin to be economical to mine, but it’s honest-to-goodness coal.

Whereas the coal of Europe and the eastern United States is most Carboniferous in age (over 300 million years old), the coal of the western United States is mostly Cretaceous in age (around 80 million years old). So western coal is “young” coal while eastern coal is “old” coal. As far as I know, there’s no systematic difference in quality, except the older coal is a little more likely to be metamorphosed into anthracite, ideal for coking for steel manufacture.

Further up canyon, I approach the Red Narrows.

I’ve examined this before, but it’s interesting enough for another look.

The conglomerate beds I recognized as upper North Horn Formation, which spans the Cretaceous-Paleocene boundary, 65 million years ago. But I find myself wondering if the lower beds are much older beds from which the upper conglomerate eroded. There are more down the road:

This may be Flagstaff Limestone, exposed along a fault. But my guess is the fault on my map is beyond the hill, and this is just a different facies of the North Horn Formation. Still, I’d never noticed it before – the conglomerate is more spectacular.

It looks from my map and its description that this is the weak unit responsible for the mudflow that drowned the little town of Thistle in April 1983.

I finish my drive into Provo, turning up my music to help keep me alert. Ironically, it’s all classical; I brought no rock music.

I arrive at Mom’s and settle in for the weekend. She takes me to dinner at her favorite lunch place. I leave about half my dinner on my plate because it’s too much carbs for my system. Otherwise, decent food.

Next: A brief interlude, Hell’s Half Acre, and a first taste of Yellowstone.

*Milk preserved by packaging it up then bombarding it with high-energy electrons to completely sterilize it. It’s a cost-effective way to preserve fresh milk in a form that keeps for a long time at room temperature. The correct term is irradiated milk, since the electrons are indistinguishable from beta radiation, though they’re not produced by nuclear reactions. This is all very ironic, given that this stuff is prominently labeled as “organic.”

Pingback: Great American Eclipse wanderlust, day 1 | Wanderlusting the Jemez

Pingback: Great American Eclipse wanderlust, days 3 and 4 | Wanderlusting the Jemez