Wanderlusting Tetilla Peak

The 27th Annual Kent Is No Longer 29 celebration kicked off last Friday morning. Gary Stradling picked me up in his jeep and we headed to La Cienega, where the geologic adventures would begin.

I have been up into the Cerros del Rio once before, on my birthday celebration two years ago. That time, I was traveling alone in the new (to me) Wandermobile on reconnaissance. This time, since I was more familiar with the area, and since I had a hiking partner, I planned to venture further from the road by hiking to the top of Tetilla Peak.

After pausing momentarily to admire the contact between the 3-million-year-old Ancha Formation with the 40-million-year-old Galisteo Formation, we headed into the village and stopped at the hornblende andesite plug that dominates the village center.

La Cienega turns out to be a geologically very interesting place, well worth spending some time in. Mesozoic formations are exposed to the west along the La Bajada escarpment, which is part of the eastern boundary of the Rio Grande Rift. The Rift is a great crack in the Earth’s crust extending from central Colorado to El Paso, which opened when the Colorado Plateau began pulling away from the rest of North America 30 million years ago. Closer to the village, the oldest exposed rocks belong to the Eocene Galisteo Formation, which appears to be around 40 million years old. This formation was laid down in a river valley that likely covered the entire Jemez area, at a time when the Sierra Nacimiento had already risen and the Pajarito Uplift occupied the area between Santa Fe and Los Alamos. The opening of the Rio Grande Rift threw down the Pajarito Uplift and turned it into part of the Espanola Basin, and the former uplift surface is now buried under hundreds of feet of rift fill sediment. We know it’s there from drilling and from geophysical measurements.

Around 34 million years ago, volcanoes erupted along a belt reaching from east of the present-day Sandia Mountains to the La Cienega area. This belt, the Ortiz Porphyry Belt, included numerous large intrusions of magma into the crust that solidified underground as the Ortiz Monzonite. The magma that made it to the surface was erupted as the Espinaso Formation.

The hornblende andesite plug in the center of La Cienega is mapped as part of the Espinaso Formation. I showed Gary some of the many xenoliths, bits of country rock entrained in the magma while it was liquid, that are visible in the plug. I’ve photographed some of these before, but I spotted one I hadn’t photographed that seemed worth the attention.

There are three xenoliths in the photograph, a large one at center and two smaller ones to the left. They all appear to be composed of a granite or granite gneiss, probably from somewhere in the middle crust. They were caught up in the andesite magma without melting and carried to the surface. Xenoliths are not uncommon, but this particular andesite plug seems unusually rich in them.

The andesite itself is a rather pretty rock, with numerous small needles of black hornblende. Though not large, these are beautifully crystallized, with the crystal faces very evident — euhedral phenocrysts. Here phenocryst means a larger mineral crystal in an otherwise fine-grained igneous rock; euhedral means that the crystal had plenty of room to crystallize into a characteristic form, unhindered by nearby crystals.

Gary was eager to climb all over this knob, and who could blame him? I was eager to see if I could find a xenocryst that was from the upper mantle rather than the crust. This was the only really good candidate I could find:

I tried to convince myself this was mantle rock composed of pyroxene (black material) with the other characteristic mineral of mantle rock, olivine, weathered to iddingsite. On reflection, mantle xenoliths are actually very unlikely in an andesite like this. While andesitic magma may form directly from mantle rock in volcanic arcs, andesite in a continental setting like La Cienega is almost certainly an evolved magma, formed when more primitive magma from the mantle stagnates in the middle crust, crystallizes out some of its more silica-poor components, and incorporates some crust melt. Such rock is very unlikely to preserve mantle xenoliths. My guess is that this is not a xenolith at all, but a clot of hornblende that formed in the andesite.

Gary has excellent beginner’s luck. He found a xenolith that appeared to be composed entirely of moscovite, potassium mica. This is very unusual. I may have to take a closer look; Gary wondered if it might be pyrite. Very unlikely … but then I would have said that of muscovite.

We would have had better luck hunting mantle xenoliths in the Cieneguilla Basanite, which crops out at Cerro Seguro and many other locations north of La Cienega. The Cieneguilla Basanite formed from primitive magma, straight from the upper mantle, that was very low in silica and somewhat elevated in sodium. Published reports indicate that mantle xenoliths have been found in this formation.

Gary had chosen to park in a convenient driveway. As we prepared to leave, the local resident hurried up to talk to us. Turns out there have been a rash of burglaries in the area, and we looked suspicious. We were able to reassure her that we were harmless amateur geologists. My impression is that gentrifying areas like La Cienega often suffer from a high rate of property crimes.

We proceeded on past exposures of Ortiz monzonite and breccia of the Espinaso Formation to the La Cieneguilla petroglyphs. A short hike took us to the edge of Tsinat Mesa, where the petroglyphs were inscribed on hawaiite (sodium-rich basalt) of the Cerros del Rio Formation.

Sheep and thunderbird:

Maize symbol, partially hidden in shadow.

Gary has better social skills than I do, and struck up some wonderful conversations with other hikers in the area. There was a group from upstate New York, and a few others from Colorado, Vermont, and Texas.

The cliffs here form the eastern escarpment of the Cerros del Rio, a basalt plateau divided by the White Rock Canyon of the Rio Grande. This plateau formed around three million years ago as a monogenetic volcano field, a field that erupts fairly low-silica magma through numerous small vents, none of which erupts more than a handful of times. Such fields likely form where hot mantle comes close to the surface where the overlying crust is relatively cold and dense but has been fractured. This area fits that description well: the Rio Grande Rift has provided the fractures, and the hot mantle is provided by western North America drifting onto the East Pacific Rise.

On the west side of the river, the basalt is partially covered by younger mesas of the Bandelier Formation, but it is exposed around White Rock, which is why that area has level, open round suitable for building a bedroom community for Los Alamos. East of the river the plateau is fully exposed and accessible by dirt road. It is split between Santa Fe National Forest, BLM, the state of New Mexico, and Cochiti Pueblo.

We drove up onto the Cerros del Rio, passing a cinder code exposed by a road cut and crossing Tsinat Mesa. The road follows power lines, then abruptly turns north immediately after crossing onto Santa Fe National Forest land. Here Gary wanted a photograph of the two of us for the occasion.

I’m the guy with the sunglasses whose head is smack in the way of Tetilla Peak, our destination for the morning. We found a side road that headed more or less directly to where we wanted to start our hike, parked, and paused for lunch.

Rebecca, Gary’s wife, apparently purchased a number of these camp chairs, and I’m glad to show her that Gary made good use of one.

Lunch consumed, we headed for the peak.

We were already high enough for a nice view to the northwest.

(Click to enlarge.) We are looking into the heart of the Jemez. The knob at center on the skyline is Redondo Peak, located in the center of the Valles caldera, and the third highest point in the Jemez. Directly in front of it are the tan hills and peaks of the San Miguel Mountains. These were a small volcanic center 8 to 9 million years ago, and most of the volcanic beds are assigned to the Paliza Canyon Formation. At far right in the near distance is the flat topped Colorado Peak, a relatively young cinder cone of the Cerros del Rio at around 2.6 million years in age.

It took less time than I expected to hike to the top of the peak. Here we found a USGS benchmark (curiously, with an engraved serial number but no altitude) and a rock cairn. I took a number of panoramas.

Here is a 360-degree panorama from the top. I was careful to level my tripod but inadvertently set my camera to the close up setting. This didn’t seem to hurt any:

The pan starts with Sandia Crest to the south at left. To the west is the La Bajada escarpment and Santa Ana Mesa. Then comes the Jemez and the San Miguel Mountains. At center, to the north, are Colorado Peak and the Twin Hills massif. Then comes the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and Santa Fe at their feet. To the southeast is La Cienega and the Cerillos Hills.

Southwest of Tetilla Peak is a partially buried cinder cone:

This was likely an important source vent for the unit mapped as the Basalt of La Bajada. If you look closely at the full resolution image, you can just make out a darker stripe running up the left side of the knob. This is a small dacite dike.

Basalt: This is a common volcanic rock with a fairly low silica content that is usually quite dark in color. Dacite: This is a much more silica-rich rock that is typically lighter in color. Since magma is more viscous the more silica it contains, basalt tends to flow out freely to form flat flows while dacite tends to pile up as domes and plugs.

A couple of deep telephoto shots. First, the southern San Miguel Mountains:

In the background is Redondo Peak. The knob at left in the middle distance is Cerro Balitas and the knob at right is Cerro Picacho. Both are composed of Bear Peak Rhyolite. Rhyolite is even richer in silica than dacite, and contrasts with the surrounding Paliza Canyon Formation andesite, which is intermediate in silica content. The Bear Peak Formation erupted between six and seven million years ago and so is, on average, a bit younger than the Paliza Canyon Formation, and typically intrudes and overlies the latter formation.

Between the two knobs is Sanchez Canyon, which exposes some of the oldest high-silica rocks of the Jemez volcanic field: 13-million-year-old rhyolite assigned to the Canovas Canyon Formation.

A zoomed view of Colorado Peak.

The flat top is dished enough to be interpreted as a crater, and is surrounded by a ring dike of solid rock that contrasts with the cinder making up most of the peak. You can make out part of the ring dike if you click for the full resolution version.

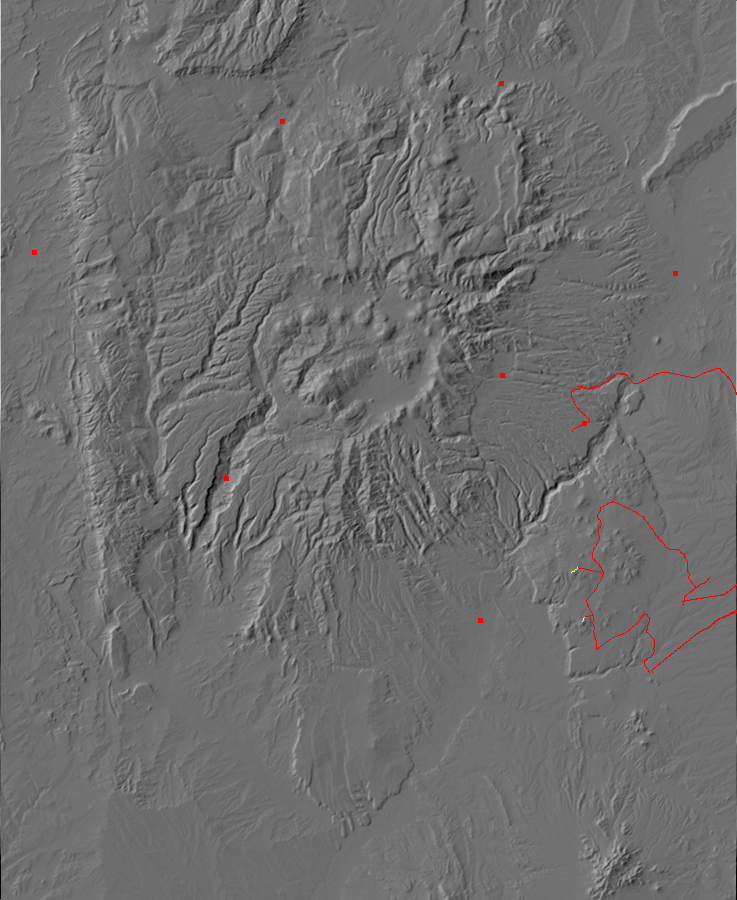

My desire to climb Tetilla Peak was fueled by the expectation that it would be a good place to get a panorama of the Cerros del Rio for the book. I moved to a point on the northeast side of the peak for this one.

At left is Colorado Peak, and beyond and to its right is Montoso Peak, just peeking over a ridge, and Cerro Micho, the highest point in the Cerros del Rio. Then comes Cerro Ruiz and the Twin Hills complex. To their right we look towards the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and Santa Fe. Then comes some low unnamed domes, and, at right, Tsinat Mesa with the Cerrillos Hills and Ortiz Mountains beyond.

Another zoom shot, of the Twin Hills complex:

I think that’s the Twin Hills just poking over the ridge at right. At left is Cerro Ruiz.

And Colorado Peak, again.

Behind it and to its right, just peeking over the ridge, is Montoso Peak. At furthest right is Cerro Micho.

The steep knob forming the peak of Tetilla Peak is underlain by dacite.

Notice the white phenocrysts of plagioclase feldspar, typical of andesites and dacites. The dacite of Tetilla Peak is the most “evolved” magma in the Cerros del Rio, meaning that it has experienced the greatest loss of heavier minerals through partial crystallization prior to being erupted.

The power of living organisms.

Gary was intrigued by a reflection of some kind in the woods towards the base of the peak, which appeared to be at the end of a faint jeep trail. We headed that way, and found:

The reflection Gary spotted was the solar panel atop the pole, with cables running to the Yagi antenna and the buried barrels. The Yagi points towards Los Alamos; I’m guessing this is a station of the LANL seismic network. We were careful to leave it alone, though our footsteps might have generated a slight local earthquake.

This area is below the dacite cap of Tetilla Peak and onto its andesite shoulders.

A pretty hornblende andesite, somewhat resembling the Espinaso Formation plug in La Cienega, though the latter is ten times older.

Rock cairn, indicating this is a recognized hiking route.

We found our way back to the jeep and returned to the main road. The day was still young; we decided to take a crack at Colorado Peak, turning at the Twelve Hundred Well corrals onto a loop that our map showed passed close to the hill. We found a good spot and parked.

The lower slopes of the hill are a mass of cinder, as is most of the hill itself.

There are occasional flow-banded massive blocks, probably eroded from the ring dike atop the hill.

This rock is described in the geologic report for this quadrangle as an andesite, but one on the low side in its silica content — bordering on basaltic andesite. The flow bands are characteristic of magma that is still slowly flowing as it hardens.

Patches of snow are still present on the north side of the hill.

Before long we reach the ring dike.

From here, there is an excellent view to the north.

Jemez at left in the distance. At center is Montoso Peak, which is prominent on the skyline south of my home in White Rock. You can just see the westernmost part of White Rock peeking over the left shoulder of the peak, with the white storage buildings of one of LANL’s waste storage areas beyond. To the right of Montoso Peak is Cerro Micho, then Oriz Mountain, then finally the Twin Hills area at furthest right.

We looked for the car for our return hike. It took some time to spot it, well to the east of where we had thought. Would have been a long and unpleasant hike back if we had not spotted it.

Close up of the top of the ring dike.

For some reason, my GPS lock was between a hundred and three hundred feet south of where we actually were. It’s usually better than that. Perhaps the terrain.

‘This was an excellent spot for a panorama of the San Miguel Mountains.

Cerro Balitas and Cerro Picacho are at left. Just left of center is St Peters Dome, then Boundary Peak, then the back wilderness of Bandelier National Monument.

The andesite at the top is variegated:

I vandalized a piece, and found that it is mottled red and black all the way through; this is not just surface weathering. This suggest prolonged hydrothermal alteration.

To the west is Cochiti volcano.

This is located on tribal land, so this is probably the best photograph I’ll ever get of this one. This is the youngest volcano in the Cerros del Rio, with an age of just 1.5 million years. This is actually after the Toledo eruption in the central Jemez, so the last gasp of the Cerros del Rio field (at least so far) overlaps the great caldera eruptions of the central Jemez.

Far to the west is a landform I’ve noticed before but not been confident I had correctly identified.

This time it’s lined up with Mount Taylor, and I know where I am (Colorado Peak) and I can draw the line on the map aaand …. it appears this is Bodega Butte. The geologic map tells me it’s Santa Fe Group rift fill sediments capped with basalt of the Paliza Canyon Formation, probably close to 10 million years in age.

I clambered down the ring dike here to get a good picture of the dike. My GPS was finally getting an accurate lock.

We started back, taking a minute to again check carefully for where the jeep was.

We returned to Santa Fe by continuing on the main dirt road north. I took just a couple more pictures. This knob caught my eye for no particular reason:

It’s an outlier of Cerro Micho to the west, underlain by basaltic andesite. It turns out a geologist sampled the rock at the top for full analysis, finding an age of 2.73 million years, a silica content of 52.4%, and other compositions typical of an olivine basaltic trachyandesite. That is, fairly low in silica and a bit enriched in alkali metals, with the silica low enough for olivine to be present.

There was a borrow pit on the west flank and a road towards the summit. Gary could not resist. Up we went:

To the north, there’s a nice view of White Rock, framed between Montoso Peak to the left and the Ortiz Peak flows to the right.

We continued north and then east and back to Santa Fe, enjoying a nice dinner at El Parasol before returning to White Rock.

Where I found my daughter standing in the door scowling. They had been trying to call me, but my cell phone was not working. (We’ve now ordered a replacement battery in hopes that’s the problem). Laci looked okay when I got up in the morning, but then her eye swelled up something awful, they had rushed her to the local vet, and he had given us a referral to an emergency vet hospital … in Albuquerque.

So it was an hour and a half down to Albuquerque; an hour with the vet, who told us the dog was likely going to lose her eyes; and an hour and a half back with new medicines. Another trip down yesterday (Monday) for followup with the doggie opthalmologist, who confirmed both eyes were completely shot, and the left eye was causing pain and would have to be removed. I left her overnight, they removed the eye today, and tomorrow morning I drive back down yet again to pick her up. Cost: Closing in on $3000. For a 14-year-old dog. Well, she’s in good health otherwise; it just doesn’t seem right to put her down yet.

In two weeks the Los Alamos Geological Society is visiting the Harding Mine. After describing its wonders to Gary, he decided to join LAGS so he could go along as well. Should be a lot of fun.

Kent, it was a really great trip. Thanks for sharing your birthday adventure.

Pingback: Wanderlusting Tyuonyi Overlook | Wanderlusting the Jemez