The road to Jaramillo

I can’t resist that title, which is also the name of a celebrated book on the history of how radiometric dating and magnetic reversals led to the acceptance of the theory of plate tectonics. One of the crucial magnetic reversals was the Jaramillo event, named after a little creek in the Valles Caldera near the flows whose magnetic orientation and potassium-argon dates were one of the final clinchers for plate tectonics.

I hiked up the road to Jaramillo yesterday.

Because access to the area requires a back country permit, and only 35 are given out per day, I had to get up early (6:00, still later than a normal work day) in order to get breakfast, get packed, and get to the preserve headquarters before it opened at 8:00. In any case, Cindy needed me home by 1:30, so the early start was required to have a decent amount of time on the trail.

I don’t think I’ve been in the caldera that early in a long time, and there was just enough haze to bring out distances better than usual. I took a panorama from the scenic stop on State Road 4.

The haze highlights the fact that Cerro Medio is in the foreground in the last two frames, with Cerros del Abrigo looking over its shoulder in the third frame, and Cerros de Trasquilar still further distant. Beyond, on the right side of the second frame, is the north caldera rim. Redondo Peak fills the first two frames, with Redondito on the right edge of the first frame, and Pajarito Mountain dominates the east caldera rim in the last frame. Shell Mountain peeks out between Cerro Medio and the east rim.

I got to the headquarters a bit early, and waited with about four other groups for it to open. I spent a few moments talking to the father and (adult) son in front of me in line; they were from Colorado and were ambitious of catching some trout. Then the place opened, we trooped in, and took turns getting our back country permits.

“What’s your cell phone number?”

Beats me. I never call myself.

“Well, be certain to check in before you leave then. We don’t want to have to go hunting for you.”

Well then.

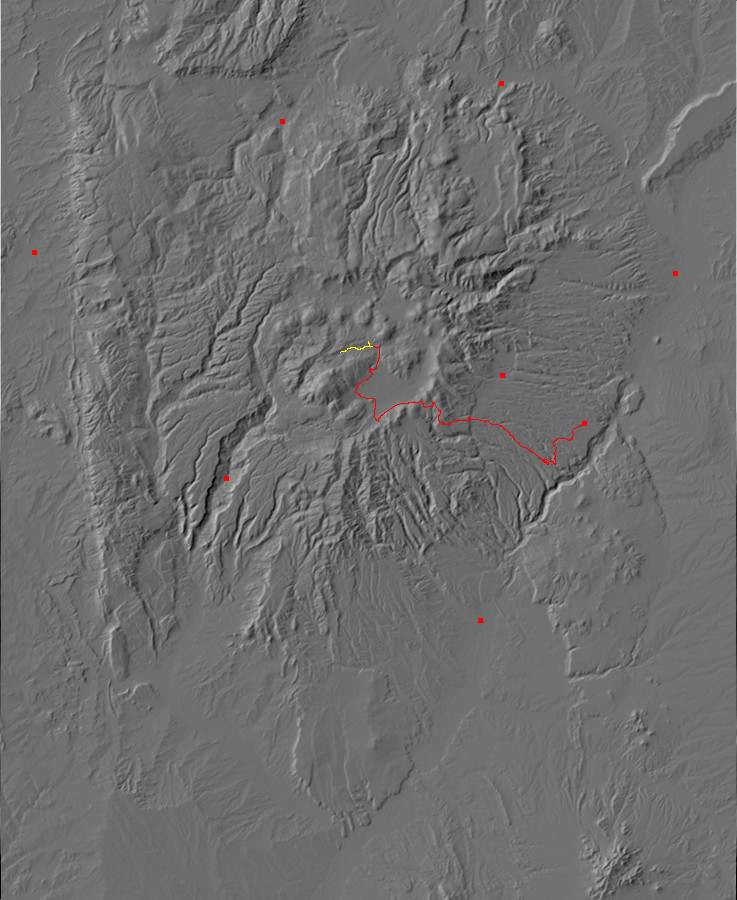

My original plan was to drive as close to El Cajete as the permit permitted, then hike the rest of the way. But it turns out there’s nowhere to park at the turnoff, though a shuttle could take me there without me even needing a back country permit. The shuttle schedule was a bit uncertain, so I decided to try that another day, when I wasn’t as constrained on time. I declared myself headed for Valle Jaramillo instead. I knew there were some megabreccia outcrops there that would be interesting, and I had brought the geologic map of the whole preserve, in case I had to change plans. Good thing.

I got my pass, wired the white copy around my rear view mirror, stuffed the pink copy in my shirt, and left the yellow copy with the ranger. (Even the Park Service has to do everything in triplicate.) I headed on towards the old ranch headquarters.

The building in the second photograph has an octagonal floor plan and was apparently used as a guest lodge. The buildings are now used by Preserve staff.

I drove on, pausing on the south side of Cerro Pinon to get a panorama of the caldera south rim.

To the left is Cerro del Medio. Beyond it at the right of the first frame is Cerro Grande on the caldera east rim. Sawyer Dome is near the center of the second frame, while, Rabbit Mountain straddles the second and third frame. Then comes a relatively low part of the rim, marking the northern end of Aspen Ridge, and Las Conchas at the northern end of Peralta Ridge on the left side of the fourth frame. South Mountain is in front of Las Conchas, with the foothills of Redondo Peak in the final frame.

Cerro del Medio is one of the ring domes erupted through the ring fracture formed around the caldera as it collapsed. The eruption of Cerro del Medio took place very shortly after the caldera collapse. Sawyer Dome is geophysically an extension of the east rim of the caldera, being underlain by Tshicoma Formation dacites and andesites dating back 3.44 million years, while Rabbit Mountain is thought to be a remnant of a ring dome from the Toledo caldera that predated the Valles caldera. The south rim further west, including Las Conchas, is underlain by Paliza Canyon Formation and Bearhead Rhyolite dating back 6 to 9 million years in age.

The Valles caldera itself, I should add, has been dated very accurately at about 1.21 million years old.

I drove on to my parking spot, missed it the first time, turned around when I realized I was leaving Valle Jaramillo, and finally found it. I paused for a photograph down Valle Jaramillo where it turns south.

That’s Cerro Pinon at the end of the valley. Cerro del Medio is to the left, the foothills of Redondo Peak to the right, and the south rim of the caldera is on the distant skyline.

I checked my blood sugar (slightly high, but no worries; I was about to hike five miles) and headed west.

I cut across a loop of the road, encountering some ground that looked like it mighty be boggy, but wasn’t. The hill to the right in the photograph is the eastern tip of a long ridge underlain by a patchwork of Bandelier Tuff, Deer Canyon Formation, and debris flows. Telling these apart could be challenging.

However, this part is likely debris flow.

The foreground is mapped as old alluvium, but the mass of boulders on the ridge is the tip of the debris flow. A debris flow is a kind of rockslide carried by water; it differs from a mudflow, which is mostly mud rather than rock, or a landslide, which is mostly driven by gravity. Here’s a fairly spectacular video of one.

The area north of Redondo Peak is covered with debris flows. These may have come off the caldera walls not long after it formed; the walls would have been steep and highly subject to erosion.

The individual boulders are mostly composed of a lithic-rich tuff, likely Bandelier Tuff deposited in and immediately around the caldera.

“Tuff”: A rock formed from hot volcanic ash. “Lithic-rich”: Geologist-speak for a tuff containing lots of bits of rock caught up in the ash flow before it solidified.

No samples today. I’m in the Preserve; it’s all catch-and-release rockhounding this trip.

Not all the rock in the debris flow are Bandelier Tuff. Some are older volcanic rocks of the Jemez area.

It’s hard to see from this photo, but some of these rocks show the characteristic large white crystals of an andesite or dacite. This means these are likely Paliza Canyon Formation, which is around 8 million years old.

I honestly do not remember why I took this photograph:

It’s beautiful country, though. Perhaps that’s reason enough.

But it’s had its challenges:

Some more debris flow deposits on the north side of the valley:

Further west, there begins to be exposures of Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, along the ridge.

Close examination of the outcroppings show that this is bedrock, not a debris flow.

The rock is cracked, but not tumbled at random.

The Tsherige Member of the Bandelier Tuff was formed from pyroclastic flows from the Valles eruption 1.21 million years ago. It forms most of the characteristic finger mesas of the Los Alamos area. Here we’re close to the center of the caldera, and these intracaldera tuffs tend to be crystal-rich and densely welded.

The white specks are crystals, probably of high-temperature alkali feldspar (sanidine). The dark patches were probably pumice caught up in the flow. Notice that these have been squashed flat, so that they are systematically elongated in the horizontal direction. These are called fiamme and are characteristic of a welded tuff, which is formed from ash so hot that the individual particles are soft and weld together after settling out on the ground.

Here’s something a bit unusual for this area: A tuff composed of very large chunks of rock cemented together with ash.

It looks a little like a block and ash flow, which forms when a volcanic dome collapses. It’s not typical of the Tsherige Member.

I’m not much of a wildflower expert, but I do take the occasional snapshot of something particularly attractive. I’m guessing this is some species of penstemon:

Perhaps Penstemon rostriflorus?

Further down the valley the road curves around a small knoll. And here I noticed the two fisherman from Colorado, who I had met at the Preserve headquarters, trudging down the road behind me, poles in hand.

“How’s the fishing?”

“Dunno yet.”

They continued on.

I considered. My geologic map shows that this knoll is an eruptive center for the Deer Canyon Rhyolite; the lower slopes are Bandelier Tuff, but the Deer Canyon Rhyolite is exposed at the top. Kind of a steep hill, and my shoulder still isn’t great …

I climbed to what I thought was the top.

The rock was covered with lichens, but I contrived to find a rock with a freshly broken surface. It looked like densely welded, crystal-rich tuff. Or it could be a rhyolite.

Only when I got home, and checked my GPS reading for this point, did I realize I had stopped at a mere ridge below the top, and not the top of the knoll. This is Bandelier Tuff. I didn’t reach the Deer Canyon Rhyolite. Well, shucks and other comments. I’m just going to have to go back sometime; I still don’t have a proper picture of a Deer Canyon Rhyolite outcropping for the book.

Descending the hill, I found that my two Colorado fishing acquaintances had found a good spot. They were fly fishing, and one was working a 12″ trout as I walked past. The other boasted that they had already caught a couple of fish. I don’t fish myself, anymore, but I was pleased for them.

Looking down the road, I could now see the main objective of my hike today.

The ridge on the skyline is a megabreccia. It’s essentially a single huge chunk of andesite from the caldera wall that slid down, more or less intact, into the center of the caldera almost immediately after it formed.

This was also a good point at which to get a nice shot of Redondito.

Redondito has the look of a dome on the north flank of Redondo. However, it’s apparently underlain by Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, and tuffs do not form domes. Perhaps there’s a rhyolite dome beneath that did not quite break the surface? Or just an odd trick of geomorphology?

The ridge ahead is underlain by a relatively small block of megabreccia. And by “relatively small” I mean only a couple of hundred feet across.

The geologic map shows the entire ridge as megabreccia, but it looks like this broke into two blocks, with a smaller block at left and a much larger block at right.

As I approached, the whitish beds just visible at the end of the ridge in the panorama came into full view.

These are lacustrine beds, laid down very shortly after the caldera formed. The caldera was filled by then with a lake, which was likely an acid, bubbling, ash-choked mess. You can see some thinly bedded layers of reworked ash at the bottom and a darker conglomerate at top. These beds remind of nothing so much as the Abiquiu Formation — unsurprising, given that the Abiquiu Formation is also reworked volcanic ash, albeit much older.

These beds are strongly indurated; that is, the sediments have been thoroughly cemented together into hard rock. Considering that they were laid down in hot water saturated with silica, this is not terribly surprising. But I could easily have mistaken these for pyroclastic surge beds if I had not had my geologic map.

The beds also dip significantly to the northeast. They were tilted when fresh magma was injected into the magma chamber beneath the Valles caldera. This magma injection pushed up Redondo Mountain, which is the type specimen of a resurgent dome.

Not much further down the road, the road cut exposed the megabreccia.

This rock is definitely andesite, though with some signs of hydrothermal alteration. It’s also a more or less solid block. It’s just the toe end of a very large block of andesite.

I hiked a bit further down the canyon, but saw nothing else new before hitting my time limit. I allowed myself a little time for a few more shots on the way back. There had been recent rains in the caldera, and at one point, there were paw prints in the mud from a dog or cat:

Not a domestic dog, since only service animals are allowed in the caldera, and I can’t imagine someone needing a service animal hiking in this far. My wild guess would be a bobcat.

I decided I was at a good spot for a panorama of the southern rim of the valley.

To the left (east), the dome of Cerro del Medio is visible beyond the valley. The northern slopes of Redondo Peak dominate the skyline. Here the underlying rock is mostly Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, with occasional megabreccias and outcroppings of Deer Canyon Rhyolite. Redondito is at right. The lower slopes of the valley wall are old landslides from the higher ground beyond.

More tracks:

I’m not sure, but from its size, I’m thinking that’s a bear track. That, or a very large wolf. But the track seems too wide for a wolf yet a bit too narrow for a bear.

My little lonely car shot for the day:

Just left of where the fence ends, waaay in the distance. (Click to enlarge). But somehow this doesn’t work as well for the new Wandermobile as it did for Clownie the Wonder Car; Wandermobile is newer, stronger, and has a higher ground clearance, which means it has to work fewer miracles for me. Not does it help that there are at least three other cars parked in that parking area.

Nearing the end of this segment of Valle Jaramillo:

Cerros del Abrigo is on the left. It’s a large ring dome, formed 970,000 years ago. On the right, crossing the boundary between the third and fourth frame, is Cerro del Medio (1.17 million years old).

Notice the very flat surface of the hills just in front of these two domes; this is puzzling. Basalt flows can produce such flat plateaus, but the lava here was all highly viscous rhyolite magma. My geologic map identifies these as erosional platforms. These would have been cut by waves in a caldera lake, which has since drained.

I returned to my car and headed out, pausing along the northwest flank of Cerro del Medio where the road cuts into the side of the dome.

Cerro del Medio is famous for its many prehistoric obsidian quarries. The beds here are devitrified obsidian, which has been exposed to enough moisture to allow it to slowly crystallize. Nevertheless, there are still isolated bits of obsidian. These can be seen in rocks broken from the beds.

The round structures in this rock are called spherulites and are characteristic of the front of an obsidian flow. There are also bits of obsidian in the nearby roadbed, such as this one.

This sample is about three inches across.

I headed on back to the headquarters, pausing at Cerro Pinon to fix the coordinates of a photograph I took last year. I’m going to have to come back to this come and climb the west side sometime; there is apparently a nice sequence of Bandelier and Deer Canyon tuffs and rhyolites. There’s no parking for back country permit holders, but it’s in easy hiking distance of the van tour to the old ranch headquarters.

Then checked in at the headquarters and headed home.