Wanderlusting Jarosa

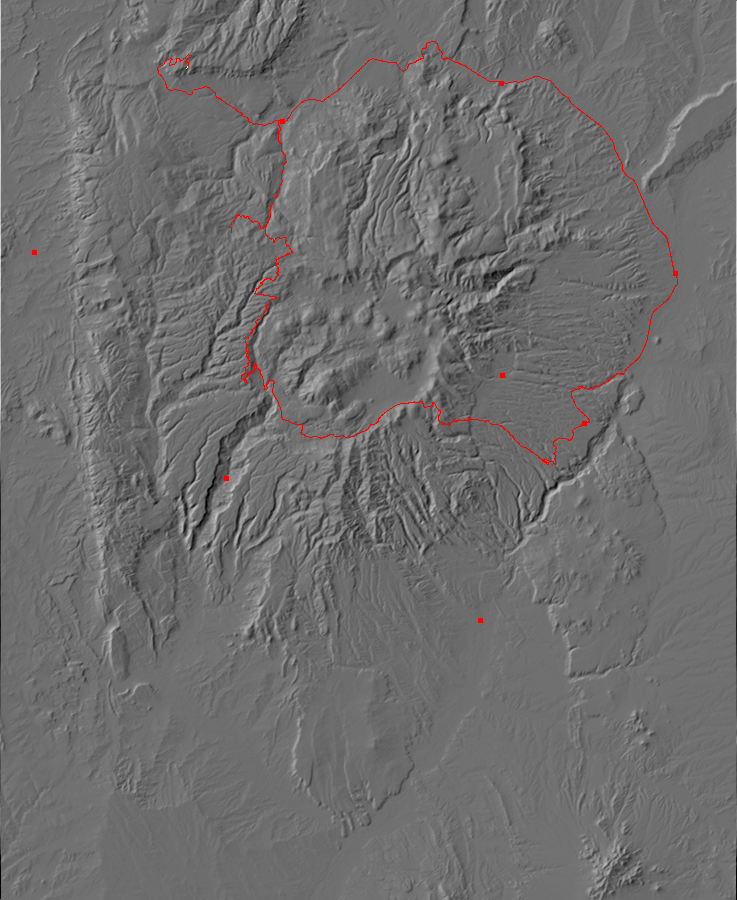

I got to looking at the “where I’ve been” map and its big blank areas that are not green (meaning not tribal lands largely off-limits to wanderlusting.)

One that I’ve been been eyeing for a while is the northwest Jemez, which I haven’t spent much time in for mostly two reasons:

- It’s the furthest from home.

- I have very little in the way of road logs for the area.

Gary Stradling, meanwhile, voiced an interest in seeing what lay beyond the Valles caldera. Perfect. We would visit the Jarosa area and start to fill in some of that gap. So Friday we headed off in that direction, with the one (not very detailed) road log I have that passes through the area.

The first part of the trip, through Espanola and Abiquiu and as far as Youngsville, is familiar ground to me, So we did not stop for pictures until we came to the crest of the road just west of Youngsville, where Mesa Naranja and Mesa Alta were impressive to our west.

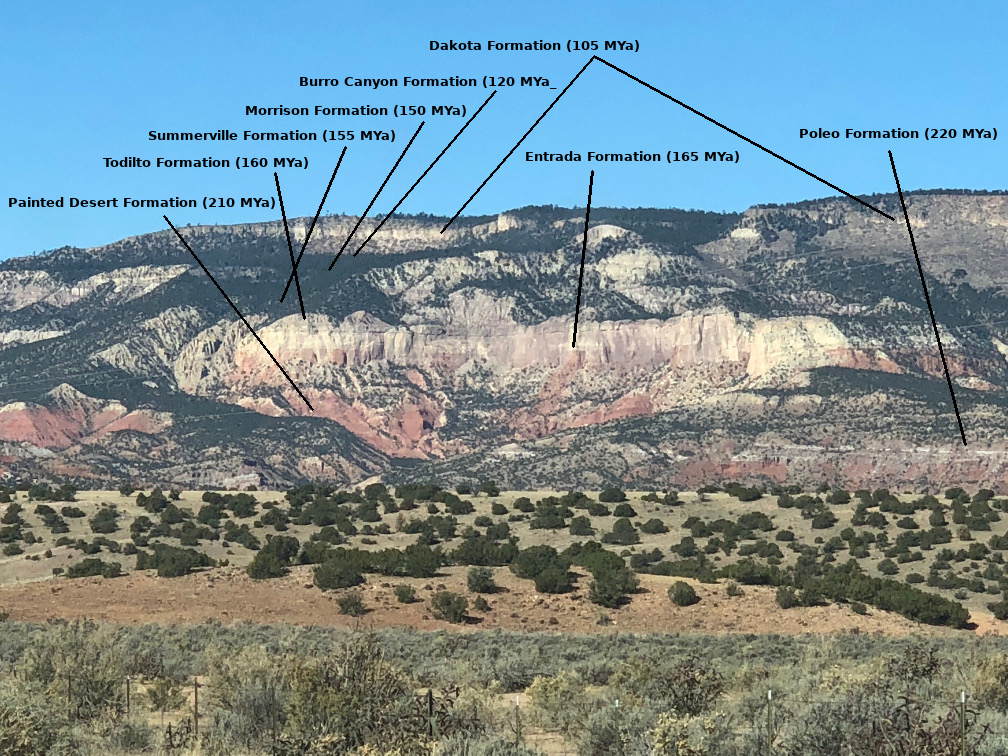

Gary is eager to learn the various formations in the mesa, and took a cell phone picture for me to annotate for him. Here it is:

According to my geologic map, only the Dakota, Entrada, and Poleo Formations are really well exposed here; the others are mostly hidden under landslides and vegetation. Still.

At about this point, Gary abruptly uttered a naughty word. He had glanced at his calendar, and realized he had a dentist appointment at noon he had forgotten about. It was now 10:30. Negotiations by cell phone followed: “How about Friday in two weeks? … No, next Wednesday won’t work … No … ” He glances at me. “I really want to get this taken care of. Would it kill you to turn around and try tomorrow?” I can do that. “I’ll go ahead and keep my appointment today …. Thanks.”

We head back.

But not without a couple more stops. Gary finds the view north across Abiquiu Reservoir enthralling, and who can blame him?

We get back to White Rock in time for Gary to make his appointment, and I spend the afternoon getting my chores done. I already have Monday committed, but my Saturday trip to Albuquerque can be postponed, so we try again the next morning. This time we are able to complete our adventure.

Which we pick up at a road cut in the Poleo Formation east of Coyote.

At least, I think so. I didn’t get a GPS fix but this is at the crest of what looks like a low fault scarp; hard sandstone on the west and soft red mudstone on the east, likely Poleo Formation and Painted Desert Formation, respectively, but the geologic map wants to call it all pediment deposits.

Gary goes looking for fossils. I warn him they’re scarce in the Poleo Formation.

Petrified wood. Gary has a knack. This would be one for the book if I was more certain this is Poleo Formation.

We stop for Mesa Naranja.

(Click to embiggen.) At far left is Loma Coyote, which we’ll get a closer look at shortly.

At left center is Mesa Naranja, “Orange Mesa”, so called for the obvious reason. The vivid orange slopes are Permian Arroyo del Agua Formation, laid down around 290 million years ago by a network of rivers flowing south off the Uncompahgre Uplift to the north. The Uncompahgre Uplift, in turn, was thrust up as a result of Africa colliding with North America as part of the assembly of the supercontinent of Pangaea. The mountains thrown up in the North American interior as a result of this collision are known as the Ancestral Rocky Mountains. They were located roughly where the modern Rocky Mountains are located, but were eroded flat by around 160 million years ago.

The top of Mesa Naranja is capped with a triple layer of Chinle Group formations. The lower layer is Shinarump Formation, composed of conglomerate and sandstone. Above are soft mudstones of the Salitral Formation, then sandstone of the Poleo Formation. The Chine Group are formations associated with the development of a major river valley, of the Chinle River, that reached from the southern Appalachians to the Pacific coast in Nevada (California had not yet joined the geological Union at the time) around 220 million years ago.The main channel of the Chinle is thought to have passed very close to the northern Jemez.

At right is Mesa Alta, whose formations I marked in Gary’s photo. The Entrada Formation was sand dunes laid down in a desert environment, while the Todilto is limestone and gypsum deposited by an arm of a shallow sea. The Summerfield Formation was tidal marshes and the Morrison was a combination of sluggish rivers and swamps. The Burro Canyon and Dakota Formations represent the return of the ocean to the area, with the Dakota being mostly beach sand.

The hill at far right is Salitral Formation over Shinarump Formation, the latter producing the knobby texture.

We return to the car and continue down the road, stopping for a telephoto shot of Loma Coyote.

The knob atop the ridge is composed of Bandelier Tuff, and is the furthest outlier of this formation in this direction from the Valles caldera. The Bandelier Tuff was laid down by two ginormous eruptions, at 1.62 million years and 1.25 million years ago, plus at least one merely huge eruption at 1.85 million years ago. The final eruption produced the Valles caldera. There is some difference of opinion on whether this outcrop was produced by the Valles eruption or the earlier Toledo eruption; the road log says Valles but it’s rather old, and the fairly recent geologic map says Toledo. I check; the lead investigator on the map is Shari Kelley. I’ll go with her identification.

We pause to admire the south face of Mesa Montosa.

and again to admire a wonderful exposure of El Cobre Canyon Formation.

The low bluff at left is underlain by El Cobre Canyon Formation of the Cutler Group. This is overlain by Arroyo del Agua Formation of the Cutler Group, which makes up most of the slop of Mesa Montosa to the right. Gary and I speculate on whether there is a fault along the base of the mesa, throwing down the El Cobre Canyon Formation, placing the contact with the higher Arroyo del Agua Formation halfway up the slope of Mesa Montosa rather than at its base. (Examining the map after I get home, I conclude that there is no fault, and almost the entire slope of Mesa Montosa is Arroyo del Agua Formation.) The rim of Mesa Montosa is Chinle Group formations.

I mentioned earlier that the Cutler Group is late Pennsylvanian to Permian fluvial deposits (river sediments) from a network of rivers running south from the Uncompahgre Uplift. Further south, in the western Jemez, the Cutler Group merges seamlessly with the Abo Formation. The Cutler Group and Abo Formation were both identified in the early 20th century at widely separated locations (the Cutler in Colorado and the Abo in the Manzano Mountains south of Albuquerque) and it was some time before it was realized that they are northern and southern ends of essentially the same unit. The resulting awkwardness was resolved by decreeing that early Permian red beds north of 36N latitude shall be mapped as Cutler Group and those south of 36N latitude shall be mapped as Abo Formation.

Gary is so intrigued by Mesa Alta that we decide we will take time to drive to the top of the mesa, something I’ve been thinking about doing for months now. I’m not sure of the road so we stop at the Coyote ranger station for directions. It’s closed, but there is a map posted, and I scrutinize it for our turn. We arrive there without difficulty and head up County Road 422 towards Santo Nino Church.

The mesa at left has no name on the topo map,but the lower half of the mesa is mapped as upper Chinle group (probably meaning the Painted Desert or Rock Point Formations)\, over which is Entrada Formation with a thin cap of Todilto Formation. It’s an older map, alas, and less reliable than the map for the area immediately east. The mesa at right has similar formations. At center is Capulin Peak, with a cap of Dakota Formation. Our road will pass through the gap between the mesas and along the south foot of Capulin Peak up to the top of Mesa Alta.

We find a really nice road cut into the Entrada and Todilto Formations.

The lower yellow sandstone is the Entrada Formation. Gary was intrigued by how soft it was in spots; its degree of cementation is pretty variable, and, in our area, it is often deeply weathered. The flat beds above are limy shale of the Luciano Mesa Member of the Todilto Formation.

The Todilto Formation was laid down in a shallow arm of the sea that was partially trapped and evaporated. Early in the process, shaly limestone was laid down when calcite precipitated from the water and mingled with mud at the bottom of the sea. At this point, there was still some life in the bottom water, and occasional fossils are found in these beds — though I found none here. As the seawater became more briny, gypsum began to precipitate out, forming the Tonque Arroyo Member which is rich in gypsum nodules and beds. Further up the road, we see this contact.

The beds above the contact with the Luciano Mesa Member are more massive and rich in gypsum. The beds at this spot are much muddier than what I’ve seen in most other locations. The Tonque Arroyo Member is fairly variable in thickness, and in the southern Jemez, gypsum is mined from locally thick beds of high purity.

In fact, we find such a bed, just a little further up the road.

That looks very much like a fault trace left of center. If so, it’s a small local fault not marked on the geologic map. As I read the rocks, the lowermost part of the Tonque Arroyo Member is muddy, and the fault has thrown down nearly pure beds of gypsum from higher in the formation to the right. These are some of the most impressive massive gypsum beds I’ve seen.

Gary and I both grab large yard rocks.

We continue up the road and find ourselves in a long north-south meadow.

The top of Mesa Alta seems to be finger mesas and meadows trending north-northeast. These are not the result of faulting, since the beds on the south face of Mesa Alta are not displaced; they are purely erosional features, and not unlike the finger mesas of the Pajarito Plateau. Here the hard cap seems to be sandstone of the Dakota Formation, with softer beds of Burro Canyon Formation sandstone, mudstone, and conglomerate beneath and then a more resistant layer of Morrison Formation sandstone (probably Salt Wash Member) forming the floors of the meadows.

We continue east across Mesa Gurule, capped with beds of Dakota Sandstone.

This is likely the Paguate Member of the Dakota Formation, a very resistant sandstone that forms prominent cliffs throughout the region north of the Jemez. It was laid down as beach sand as the ocean invaded the area in the Cretaceous. Gary and I both grab yard rocks.

We get into the next valley and decide it’s a beautiful spot for lunch. The rim is somewhere to the south, and it beckons us. A short hike brings us to a good lookout point.

(Click to embiggen.) At left on the skyline is the La Grulla Plateau, a lava plateau some 8 million years old. The snowy peak peeking over the plateau left of center is Redondo Peak, located in the center of the Valles caldera. At right is Mesa Poleo, which rises up into the northern San Pedro Mountains. These are part of a long north-south fault block that has been pushed highest directly west of the Jemez. Mesa Alta is part of the northern end of this fault block. The valley between was created by erosion into the soft beds of the Painted Desert Formation, lying between the hard sandstone of the Poleo Formation that caps Poleo Mesa and the hard sandstone of the Dakota Formation that caps Mesa Alta.

The near cliffs at center are eroded from the Toldilto Formation.

We return to the meadow for lunch. Gary produces a pistol and box of target ammunition, and gives me a quick lesson in pistol shooting. I haven’t shot a pistol since my first trip to Yellowstone, when I visited my friend, Robin Roberts, in the Denver area on my way back. We shoot about five magazine loads at a target stapled to a tree. I manage to not miss the tree with any of my shots, and in fact most of my bullets hit the target. I lack upper body strength, alas, so my hands are shaking a bit by the time I shoot my second magazine load and my accuracy suffers. But it’s probably good enough to protect myself from a large predator, if I ever decide to buy a pistol for that purpose.

It’s great fun.

We retrace our route, catching a wonderfully framed view of Cerro Pedernal through the trees.

Cerro Pedernal, beloved of artist Georgia O’Keefe, lies north of the La Grulla Plateau and is capped with a remnant of a La Grulla flow.

Another view, to the southwest.

At left on the skyline are the San Pedro Mountains. The ridge in the middle distance is a shelf of Poleo Formation, deeply eroded on its south side where the Rio Gallina has cut into soft beds of Abo Formation. No, check that; we’re north of 36N latitude, so it’s Cutler Group. As I said, I have an older map for this area. The near knob at center is the mesa north of Santo Nino Church, seen now from the other side. Just right of center is the road in and the road cut in the Todilto we saw earlier.

We head back to Coyote but pull over halfway there. Gary is interested in finding the spot we looked down from earlier. I’m interested in photographing the contact between Summerville and Morrison Formations in the south face of Mesa Alta, which shows particularly well in this lighting:

The cliffs at bottom are Entrada Sandstone, with the usual bulbous cap of gray Todilto Formation. The reddish beds above are Summerville Formation, with a very distinct contact with the light tan beds of the Morrison Formation above. Then comes heavily vegetated slopes of Burro Canyon Formation, nowhere well exposed here, and ridges capped with resistant Dakota Formation sandstone.

A panorama:

Our lookout point earlier was on the left side of the notch to the left of the highest ridge, left of center.

Cerro Pedernal and La Grulla Plateau from the west.

Cerro Pedernal is on the left skyline and the La Grulla Plateau forms the right skyline. Mesa Montosa is the red mesa at center in the middle distance. Arroyo del Agua lies at its feet.

The Continental Divide Trail is marked on the map just a hundred feet or so down the road from here. The actual continental divide is well to our west, in the Regina area, and this area is part of the Rio Puerco watershed, which drains into the Rio Grande south of Albuquerque.

Gary has been studiously working to get the name “Cerro Pedernal” tampted down into his memory. He’s been a wonderful road companion. Between Gary and Bruce Rabe, I’ve been extraordinarily fortunate in that respect.

Gary finds the view of Mesa Montosa from here breathtaking. The trick is finding a good vantage point not blocked by vegetation or structures. The north side of the road has a promising spot …

… but the power lines are a distraction. The south side of the road has a high cut in the Poleo Formation; we scramble to to the top.

Meh, still with the power lines. But, you know? With the gorgeous mesa filling the view, you hardly notice anyway.

But we did notice some colorful banding in the normally drab tan Poleo Formation.

My guess is this is relatively recent staining from water penetrating a crack in the sandstone, before the highway was blasted through this outcrop.

We return to Coyote and find our road south to Jarosa.

Bah.

Arroyo del Agua Formation in the road cut.

I got kind of lazy at this point, and did not photograph much for a while. In fairness, we were mostly in heavily forested terrain with no good rock exposures. I was navigating with the aid of my road log (which was badly out of date) and some Forest Service maps (much better). We took the Jarosa fork, to the right, here and I was briefly disoriented. Only briefly; I’m pretty good with maps and I realized we were winding around to Jarosa. This was okay; we decided to visit Teakettle Rock and then backtrack to where my road log wanted us to go.

This is eroded out of the (… checks latitude …) Cutler Group, which has scattered exposures throughout this area.

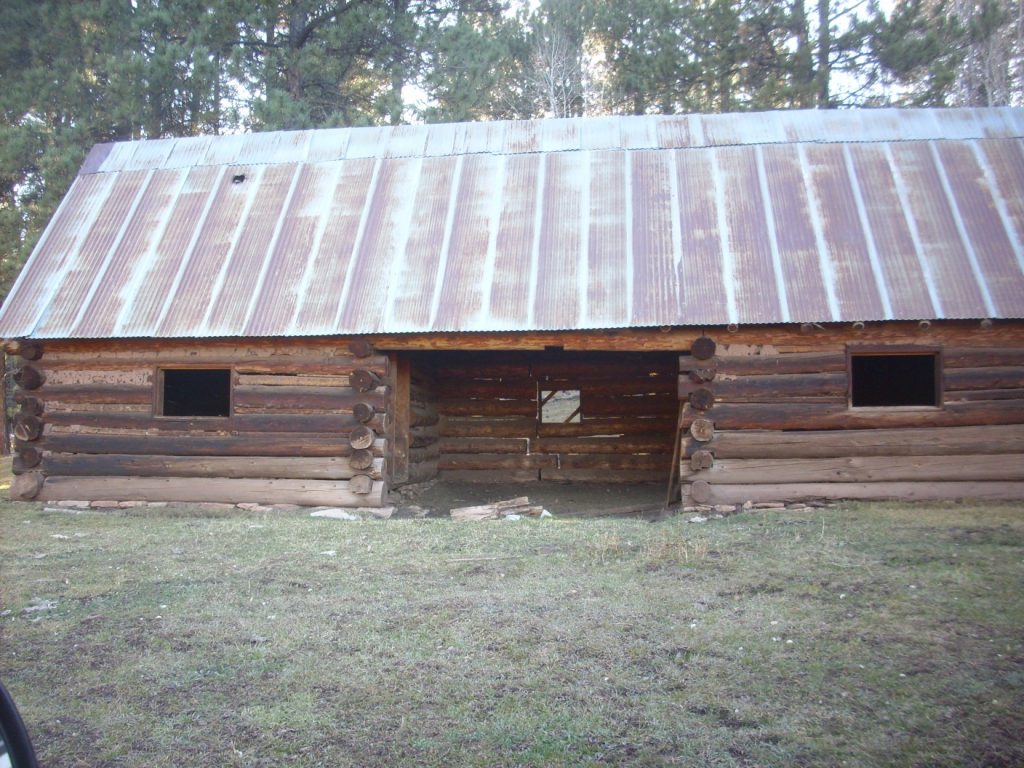

We explore locally. Jarosa is nothing more than a handful of buildings scattered across the valley. For example,

We retrace our route and head along Forest Road 453. I misjudge the distance to the first stop in the road log, which is pumice beds of the Tsankawi Pumice. This is the lowest bed of the Tsherige Member of the Bandelier Tuff, representing the start of the Valles eruption. The first stage was ejection of pumice high into the atmosphere, which mostly drifted northwest — an unusual wind direction for the Jemez, but Tsankawi ash has been identified in Utah, confirming that the weather was odd that day. We’re on the northwest side of the caldera here, where the pumice is thickest. We see lots of pumice in the road beds but I am under the mistaken impression the stop is further down; I miss the photograph.

We pass west of Cerro Pelon.

Cerro Pelon is a plug of La Grulla andesite dated at 7.81 million years old. We’re about two miles north of the rim of the Valles caldera here.

We see an elk in the road, our first significant wildlife all day. It gets off the road before I can get a decent photograph.

We reach the junction with Forest Road 144, also known as 31 Mile Road, and head west. The road begins to descend into Cebolla Canyon; my road log says to look for outcrops of densely welded tuff of the Otowi Member. We must have missed them; we turn around and try again. This is the best we can find.

But the stuff on top looks like colluvium (stuff that slid down a slope, basically) while the beds at bottom are so soft that Gary easily crumbles away a large chunk. I pull off another chunk that is full of uncharred organic debris. T’aint no welded tuff: This is alluvium, stuff deposited by water.

We head further down into the canyon, and here we find a more plausible outcrop.

It’s densely welded tuff, all right, but when I get home and check coordinates, I will find that this is Tsherige Member, not Otowi Member.

Why do I care? The stop in the road log, which we never found, is in densely welded Otowi Member. And Otowi Member is rarely densely welded; for a time this was through to be evidence of a third outflow sheet, until it was shown to be Otowi Member. Would have been a good story for the book.

We are racing daylight, but stop on the northwest caldera rim for a shot up San Antonio Creek.

The cliffs at left are part of the caldera rim, as is the distant and mostly washed out skyline. To the right are flows of the San Antonio Mountain ring dome, which is lava that came up through the ring fracture where the caldera floor collapsed in the Valles eruption 1.25 million years ago.

San Antonio Mountain.

We race south for Highway 126 to be on the paved road before dark. A final shot just north of the intersection:

And then home.

Camera update: I got word the camera is repaired; $108 more or less. Should be arriving by mail shortly. The repairs they described fit the symptoms I reported, but still: Keep your fingers crossed.

Sandstone banding maybe these; not sure, don’t look quite periodic enough.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Liesegang_rings_(geology)