A sedimental journey, days 6 and 7

The wedding morning at Scott’s house.

Mom, Lisa, and one of the cousins. Cousin is evidently more interested in the French toast being prepared than in my awful diabetic-healthy bran cereal.

The wedding is not until 1:30. I have time to get some exercise, after indulging in just one slice of French toast (with sugar-free syrup.)

I head for Logan Canyon. There is a ranger station at its mouth and rumor of a suitable trail starting there.

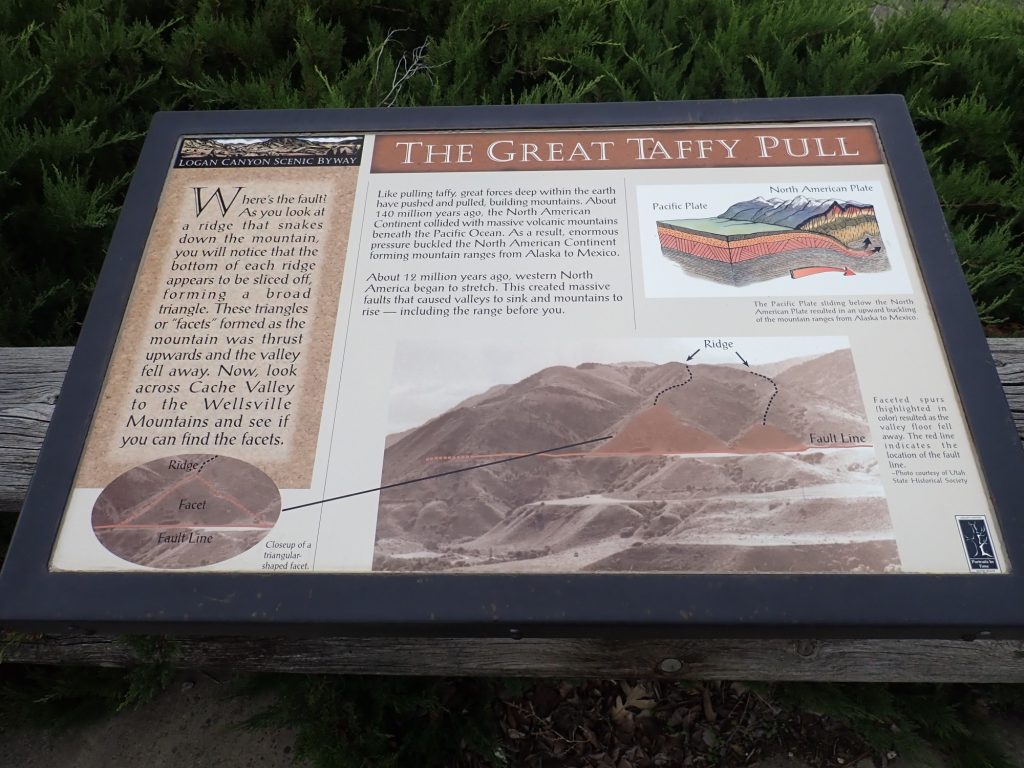

And signage.

Perhaps it’s different in Utah, but my understanding is that the Laramide Orogeny began around 70 million years ago, and crustal compression reversed into tension in New Mexico about 30 million years ago.

The station is located on one of several terrace levels left over by Lake Bonneville.

There are at least three terrace levels here. These are part of the Provo Formation, deposited on the shores of Lake Bonneville.

I see no trail head and drive further up the canyon. There is parking for Stokes Nature Center.

Across the road are cliffs of Ordivician Garden City Formation.

During the early Paleozoic (Cambrian to Silurian, about 540 Mya to 400 Mya) almost all of Utah was underwater, part of a passive continental shelf in a time of high sea level. Thick sequences of shale, sandstone, and, above all, limestone were deposited over Utah. These were thrust upward much later, starting around 70 Mya, as part of the Laramide Orogeny (orogeny meaning a time of mountain building.)

The Laramide Orogeny was probably caused by a particularly thick slab of oceanic crust subducting under western North America. Normally, when the deep mantle currents that drive plate tectonics push an oceanic plate into a continental plate, the oceanic plate subducts under the continental plate at a fairly steep angle, around 45 degrees. Volcanoes form above the edge of the continental plate, located above the point where the oceanic plate reaches a depth at which water boils out of the plate and helps melt the rock above. There is a certain amount of crustal compression at the point of contact, but it does not extend far inland — in fact, subduction sometimes pulls the continental crust apart further inland.

But the subduction of the slab of unusually thick oceanic crust, the Farallon Plate, was at a much shallower angle. Volcanoes appeared farther inland, and the shallow subduction compressed the entire western part of North America. The crust buckled and heaved in many places, throwing up high mountains along north-south faults.

Later, as North America rode up onto the East Pacific Rise, the Farallon Plate disintegrated and sank into the mantle and hotter mantle rock rose to take its place. This simultaneous stretched the crust back out again and uplifted it, producing the Basin and Range.

Logan is located on the easternmost edge of the Basin and Range, in a deep valley where a block of crust dropped between two rising mountain ranges. The mountains to the east of Logan, the Bear River Range, have inactive thrust faults at their western base, where rock was pushed upward and over younger rock during the time of compression. Now the very base of the mountains is defined by an active normal fault, where the valley floor is dropping relative to the mountains as the crust is stretched back out. My hike today will begin just east of the thrust faults.

I cross the highway to Stokes Trail and look back at the Garden City Formation on the north side of the highway.

Incidentally, I offer no warranty on formation identifications; I’m a long way from home and I’m doing my best to navigate by geologic map. But this rock fits the description. Note that the beds are dipping at a moderate angle to the east (right). The entire Bear River Range is tilted in this manner.

The road to Stokes Nature Center.

I proceed down the trail, where I get another glimpse of the outcrop across the river and highway.

The gentle terrain to the right is underlain by Swan Peak Quartzite, a less resistant Ordovician formation. In general, limestone is quite resistant to erosion while shale is easily eroded; sandstone is somewhere in between, with some poorly cemented sandstones being very easily eroded and well-cemented sandstones being very resistant.

Here the Swan Peak Quartzite is exposed in a road cut.

The Swan Peak is the tan beds at top. It looks like the Swan Peak sits discomformably on the underlying gray Garden City Formation limestone; that is, there is an irregular surface separating the two, suggesting the quartzite was deposited on a surface of Garden City Formation that had been previously eroded.

Formation names are taken from nearby locations. Garden City is on the shores of Bear Lake and is a familiar name from my childhood; my parents were both from Paris, Idaho, and we vacationed there every summer.

Further east.

Here the bedrock begins to disappear under debris recently eroded from above — colluvium.

I arrive at the nature center. It does not appear to be open yet.

Anyway, the signage suggests too much has been dumbed down for my taste.

I continue on the river trail past the center. There is fresh colluvium on the trail.

This looks like limestone barren of fossils. The map identifies the slopes above as Silurian Laketown Dolomite. (Laketown is another location on the shores of Bear Lake.) This is dolostone, not limestone, formed when magnesium substitutes for calcium in calcite. The process of dolomitization is not well understood, but it does not necessarily destroy fossils.

I come to an outcrop.

This formation is 350 to 600 meters thick, so it’s going to be with me a while on this hike.

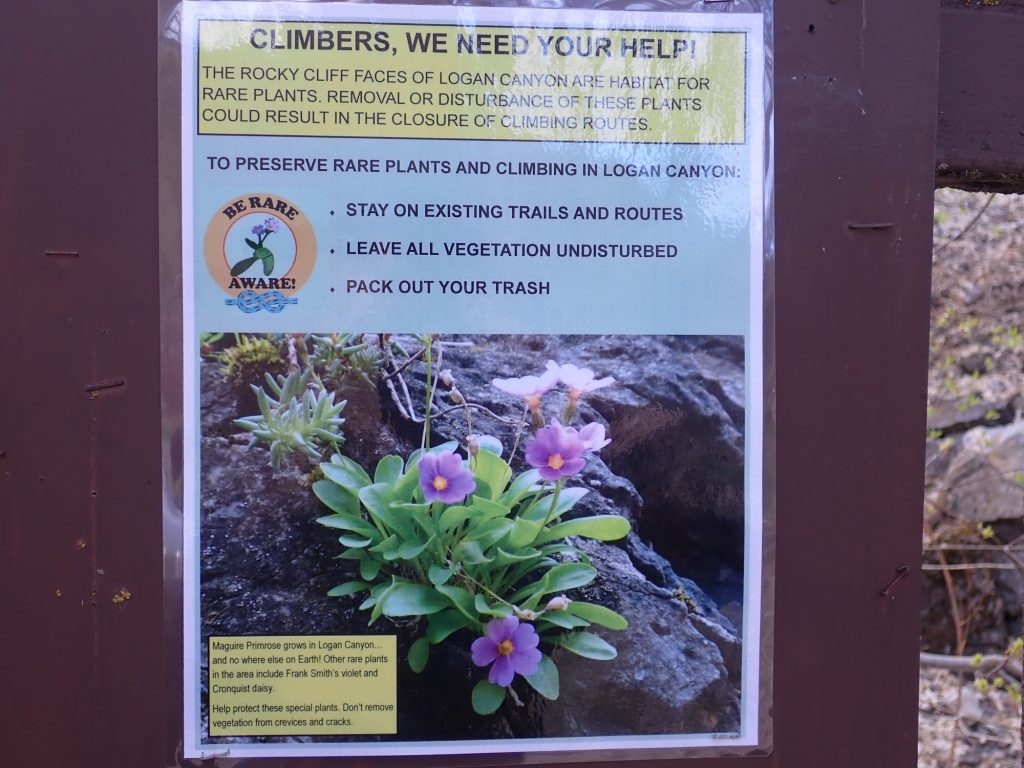

Helpful signage:

I’m not particularly itching to get off the trail.

More dolostone.

The beds still have a fairly obviously dip to the east (left). However, there is a nearly perpendicular set of joints running up and down. This is overprinting by mild metamorphosis of the beds after they were initially laid down and lithified. It is very common to find mild to severe overprinting of sedimentary beds in mountain fronts like the Bear River Mountains or the Wasatch Front, particularly close to the thrust faults.

A rare crinoid fossil.

Rare for this formation; in general, crinoids are very abundant fossils in Paleozoic beds. Crinoids, sea lillies, are distant relatives of starfish that first appear in the fossil record in the Ordovician, around 460 million years ago. They reached a peak in the Carboniferous and then declined, though there are still around 600 surviving species in the modern world. They consisted of a long stem with a cluster of fronds at the end that filtered microorganisms out of ocean water as food. What we see here is a cross-section of a crinoid stem.

I arrive at a small dam. There are water fowl.

I’m not really a bird watcher, but this looks very much like a mallard duck. By which I mean a female; a male would be a drake.

Logan Canyon has some unique plant species.

The shrubbery is thick here but it looks like a new formation is coming into view.

It isn’t. This is still Laketown Dolomite, exposed in all its glory on the open slopes north of the road.

Mostly unconsolidated debris deposited by Lake Bonneville in its prime.

First Dam is back at the canyon mouth. And, yes, there is a Third Dam, but apparently no Fourth Dam.

Mallard drake.

I finally reach an outcrop of something new: Water Canyon Formation.

This is a sandy dolostone, only subtly different from the underlying Laketown Dolomite. It is significantly younger, being a Devonian formation in the ballpark of 390 million years old.

Helpful signage.

Here the trail switches up the side of the mountain, bringing into view outcrops on the north side of the canyon.

This is the Devonian Hyrum Dolomite.

Why, yes, there is a lot of dolostone in Logan Canyon. No one knows why. In the Wasatch range to the south, there are incredible thicknesses of limestone, but these are easy enough to explain as continental shelf deposits that accumulated over many tens of millions of years on a passive plate margin. The trick is converting large masses of calcite to dolomite with magnesium-rich fluids, and we don’t really know how that works yet.

Looking up canyon:

The uppermost slopes, where the rock becomes less exposed and more tan in color, is Devonian Beardneau Formation. This contains beds of sandstone and siltstone, suggesting a lowering of sea level.

There’s a lot of trail up there.

A beautiful view of the Hyrum Dolomite across the road.

This seems interesting.

A boulder of Hyrum Dolomite which, in addition to beautiful orange crustose lichen, has seams of something in it. Chert. perhaps. Also possibly some crinoid stems, but those may be small patches of gray lichen.

I still have some time, but there’s no need to press my luck, and no great reason to think there’s some wonder just around the corner. I start back.

This is interesting, too.

I’m in a drainage, so this could have washed down from several different fomations higher in the mountains. A calcareous conglomerate of some kind.

Back at the small unnamed dam:

Boy meets girl. Seems fitting.

And this, at the nature center, I have no idea.

All I can fiure is it is supposed to be a habitat for solitary bees or other Hymenoptera.

Conglomerate in the river bed.

This could be from anywhere in the watershed, but it’s a coarse conglomerate unlike anything I saw in outcrop.

A final look at the Garden City Formation.

I wondered at the time if there might be a fault at the center of this image, but I don’t think so. The beds do look deformed but not broken.

Back home; I feast on cheese curd (a Cache Valley speciality) then dress for the temple.

As I explained in the previous post, a temple wedding (also called a sealing, since the couple are eternally sealed together by the authority of God) is a very private ceremony. There is not room for a big group of guests in the sealing room, even if it was appropriate. I am close enough family to be invited.

The sealer makes some brief remarks before the sealing ceremony.

The ceremony is brief and beautiful. Afterwards the couple exchange rings. This is not part of the temple wedding ceremony but is a concession to Western culture.

Guests not invited to the actual ceremony gather outside.

Two years ago, at a previous wedding, I took this picture.

This seems a suitable sequel.

Jeff’s sisters.

Teenage cousins on Lisa’s side. For no good reason at all, I spent half an hour telling the cousin on the left the story of Beren and Luthien from The Silmarillion and was blubbering by the end. I’m afraid I’m the weird uncle in the family.

Steve, Jeff’s brother.

Young, handsome, charming, preparing for graduate school, and single. Take note, ladies.

It is traditional for the newly married couple to emerge from a door some distance from the regular entrance, so the extended family and friends can greet them, congratulate them, and take pictures without disturbing other temple patrons.

Here they come.

Borked the focus. Crep. Good think I’m not the official photographer.

Jeff is just a great kid. Sharp as a tack, but without guile: What you see is what you get. My impression of Kelsey is awfully good as well.

Couple with grandparents. (My father passed away clear back in 1984; a year I’d love to toss down the memory hole.)

Couple with groom’s family.

I get recruited by the official photographer to do the bride’s family: She is also Kelsey’s aunt and wants to be in the photograph. Her camera is much nicer than mine. I would love to have a DSLR with a first-rate telephoto, but I have a wife, three kids, five cats, a fish tank, and a hungry mortgage to feed.

Scott’s girls with their new sister.

One of my worst memories of my own wedding was my family insisting we unwrap all our presents late into the night following a very long drive and a long open house. Jeff and Kelsey had the good sense to unwrap in the late afternoon and only as many as they felt like unwrapping. Also, no long drive. (There was not a temple in New Mexico when I married Cindy, so we were married in Denver and drove back to Los Alamos for the open house.)

Now for dinner.

Beef sandwiches au jus. With cheese.

It is early evening and we have a long drive to Provo. And the weather is deteriorating. I say goodbye to Scott, Catherine gives me a hug, I get our stuff and Mom in the car and head out. We arrive after dark but I make a sugar-free ice cream run; the dinner was a bit sparse on diabetic-friendly food, though I did ask for a small scoop of Aggie ice cream. (And got a rather large scoop. “Small scoop of ice cream: It is a difficult concept.”)

The next day is Easter. I attend church with Mom in her Provo ward. The music is quite good; her ward is in an educated area with a lot of musical talent. Afterwards we nap. Then Lori, my sister, has invited us for Easter dinner. (She was unable to attend the wedding. They had a trip long planned to visit a cousin in New Zealand when the wedding schedule was announced and couldn’t easily cancel. She got back just last night.)

Robert Raymond, my brother-in-law, is at left. Their third child, Stephanie, and her husband, Alex, are seated in the love seat across the room. Julie, Lori’s second, is sitting on the floor, facing away, and two of her children are focused on the TV. Lori is holding Oliver, Alex and Stephanie’s son. Next to Lori is her fourth, Lisa, also seated on the floor, and Lisa’s husband Hayden is sitting behind her. Julie’s husband, Matt, is at far right in the corner of the room. Matt is a podiatrist and one of the nicest guys I know. Alex I do not know as well but also like; Hayden I don’t know at all well yet (I missed the marriage because of my broken ankle) but my initial impression is good. Among other things, he has a remarkable singing voice.

Dinner is some excellent ham and various side dishes.

Lori’s oldest, Kristi, and her husband and children arrive in time for the birthday celebration. Stephanie is turning 19 again. The Raymonds know how to party.

That’s Steve, Kristi’s husband, at far right. The “cake” is a cookie pizza. It is not on my diet, but Lori has thoughtfully provided some sugar-free pudding and whipped cream so I can have a treat as well.

I take Mom home and we turn in for the night. I have a big day planned for tomorrow if the weather will cooperate. (It has threatened heavy rain all day.)

Next: Our quarry eludes us