A sedimental journey, day 10

Dawn in Shafer Canyon.

We break camp and start down Potash Road.

We are past the lowest stretch with its (not too bad) puddles.

The road approaches Dead Horse State Park, high on the cliffs ahead and to the left.

This is about where the White Rim Sandstone pinches out. The ancient beach that deposited this formation never got further east than this. The lowest beds are arkosic Cutler Formation, on which the Moenkopi Formation directly rests, followed by Chinle Formation and massive cliffs of Wingate Formation, with a thin local rim of Kayenta Formation, forming the canyon rim.

We are at the rim of the innermost gorge.

The bench here apparently divides the Lower and Upper Cutler Formation. It marks the transition from the arkosic (feldspar-rich) Upper Cutler Formation from the more limy beds below.

We have come into view of the Colorado River.

I drive on for a better view down canyon.

This makes it clearer that the lower Cutler Formation beds dip gently to the south. We are now on the west flank of Shafer Dome, where the beds are pushed upwards by a salt dome beneath. There is no visible dome on the surface, deeply cut as it is with canyons; the dome is purely “structural”, discernible only by studying the dips of the rock beds around it.

We pass south of Dead Horse Point and north of Shafer Dome. Ahead is a chimney.

The lowermost beds of the foreground mesa are Cutler Group; sitting directly on it is Moenkopi Group. Chinle Group forms the upper slopes around the chimney, while the chimney itself is Wingate Formation. Note the beds dipping towards the north, away from Shafer Dome.

Further down the road are some spectacular beds on the east face of Dead Horse Point.

Shafer Basin and the park boundary.

The pond at left is a potassium evaporation pond built by Texas Gulf, purchased by Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan in 1995, and purchased again by Intrepid Potash in 2000.

Shafer Dome contains salt, but it also contains beds of sylvite (potassium chloride), a potash mineral. This was originally mined conventionally from deep shafts, but (for reasons we’ll get to shortly) the company switched to solution mining in 1970. Water is pumped into the sylvite beds, dissolving the sylvite, and then is pumped back to the surface to evaporation ponds.

Desert onion.

I walk over to get a clearer view of the evaporation pond. The camera blinks “BATTERY EXHAUSTED.” Crep. I trudge back to the car, put in the spare, and trudge back towards the pond.

Industrial processes fascinate me. I wonder how pure the sylvite is coming out of the ground, and what steps, if any, are taken to purify it further. I’ve bought sylvite as fertilizer that is probably fresh from the deposit, practically unprocessed, judging from the grain size and the presence of red clay.

We drive past the next pond.

Unsurprisingly, the ponds seem to be operated in shifts. The last pond was clear blue water (full of dissolved sylvite); this one is largely evaporated and the potash is being loaded in trucks.

Viewing the whole operation.

Perhaps there’s a reason by BLM prohibits dispersed camping here…

Nah, probably not. My three guesses are (1) fears about environmental impact, (2) to get you to pay for a spot in the developed campgrounds up the river, or (3) sheer bureaucratic arbitrary exercise of authority.

Dispersed camping: This is basically where you pick your own undeveloped camp site for free. There are some regulations and limits on group size. (The members of my LDS men’s group learned about the limits on dispersed camping the hard way last spring.) Dispersed camping is permitted on most BLM and National Forest lands, but there are local exceptions, and the ranger informed us yesterday that Shafer Basin is one of them.

We see a couple of places where folks are doing it anyway.

We arrive at the landing on the Colorado River near the potash plant. My map indicates that there should be Honaker Trail Formation at the marina. Sure enough, there are impressive limestone beds here.

It looks very much like someone tried to blast a road through the rock here and then thought better of it.

The Honaker Trail Formation is a Pennsylvanian formation, the oldest exposed anywhere in Canyonlands that I’ve been able to get close to. It corresponds with the Madera Group back in the Jemez.

Crinoid stem fossils.

These were the only fossils I found in this otherwise barren limestone. I didn’t bother to take the rock; I have some excellent crinoid fossils from Pennsylvanian limestone back home. Still, it confirms this is a marine limestone, and crinoids were particularly common in the Pennsylvanian, though that’s not conclusive of age — they arose earlier and are still with us today.

Ripple marks.

I suspect the irregular pattern shows these formed on a sea floor from wave action, with no particular preferred direction.

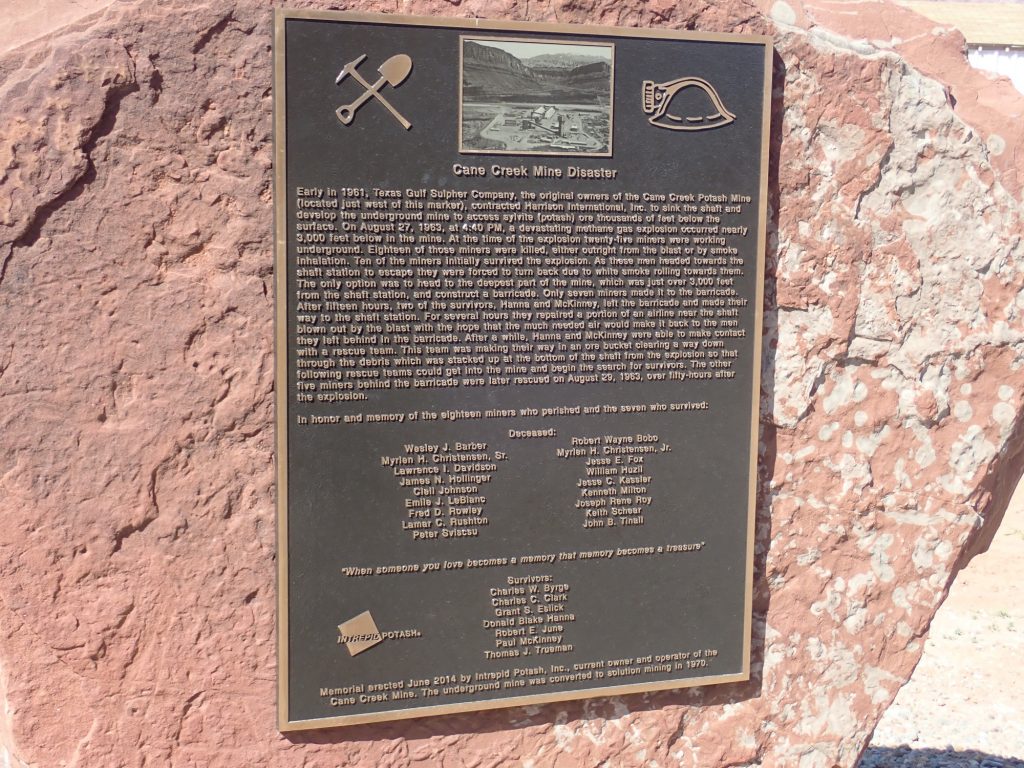

We drive past the potash plant, Gary spots a sign and we back up. This is why the potash is extracted by solution mining nowadays:

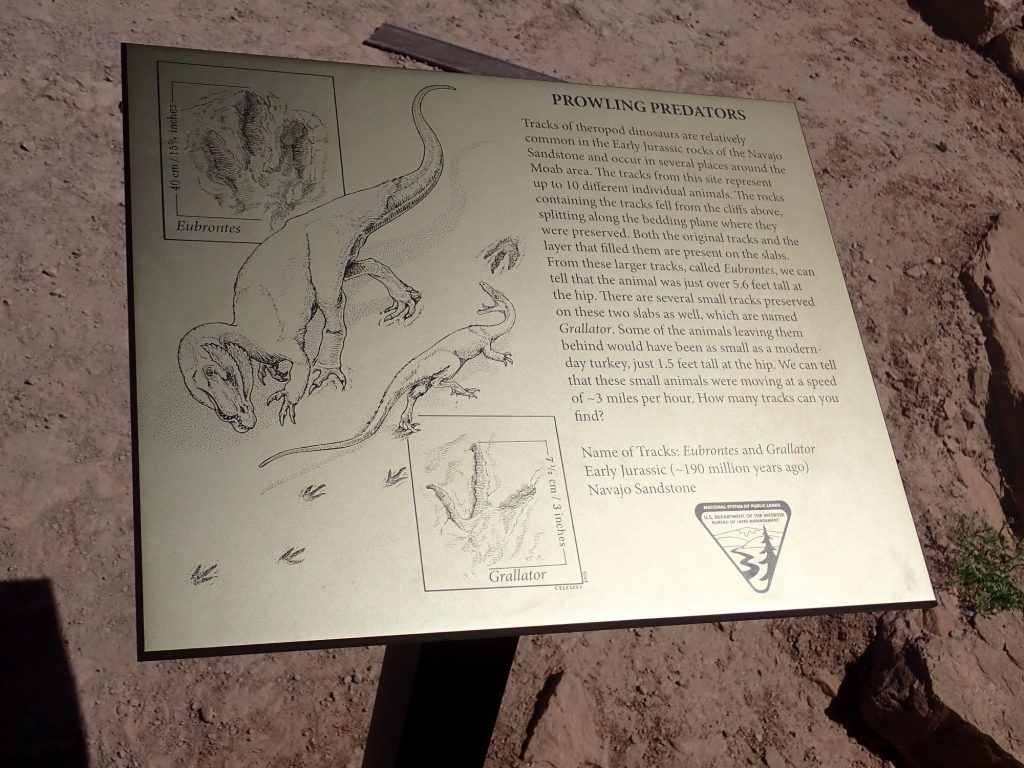

We proceed to the parking area for Poison Spider Trail and the dinosaur tracks.

The parking lot is built on the Kayenta Formation, which is also where the tracks are found.

Explanatory signage.

The area directly to the east is broken into fins of rock running east-west, so that we are looking directly down the fins.\

This is the same pattern of fracturing tha produces arches in the Entrada Formation in Arches National Park to the northeast. However, this is the Navajo Sandstone, no arches are found here, and the geologic map shows no structural feature responsible for the fins. There is a syncline mapped, but it crosses the area at an angle to the fins. Go figure.\

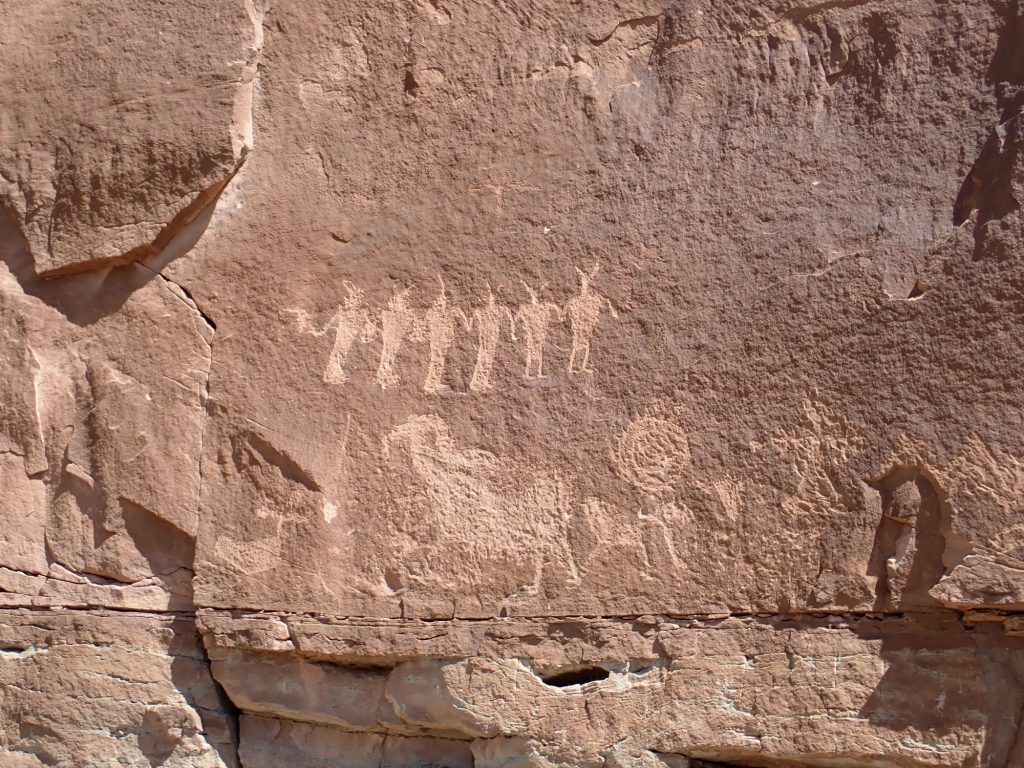

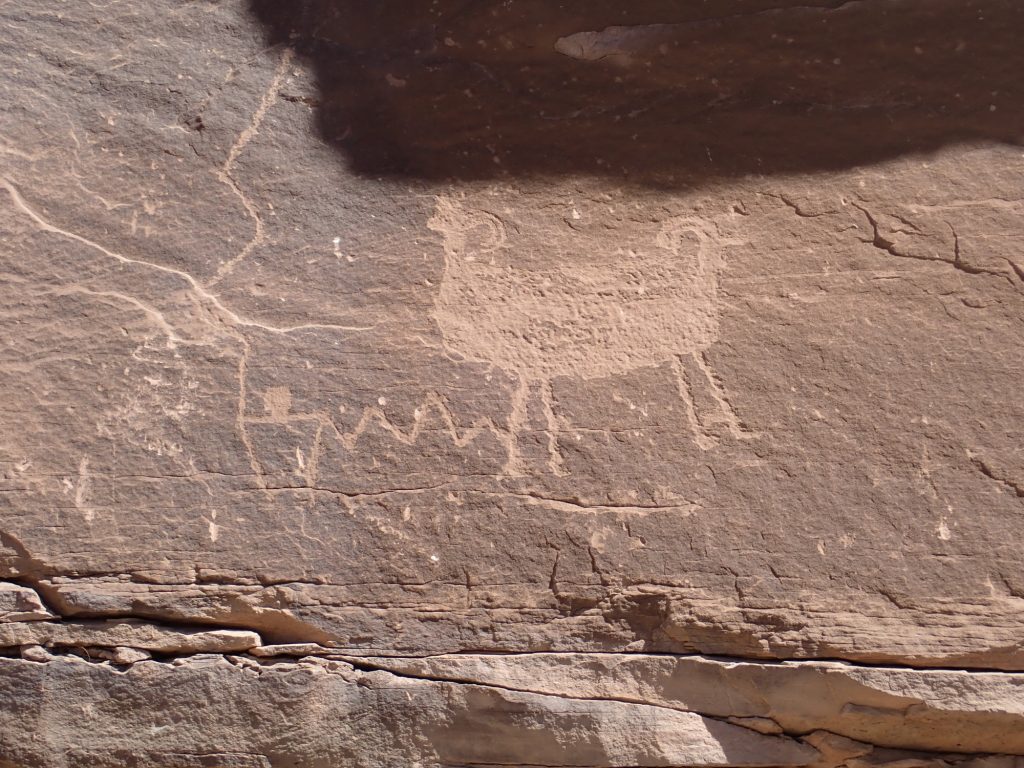

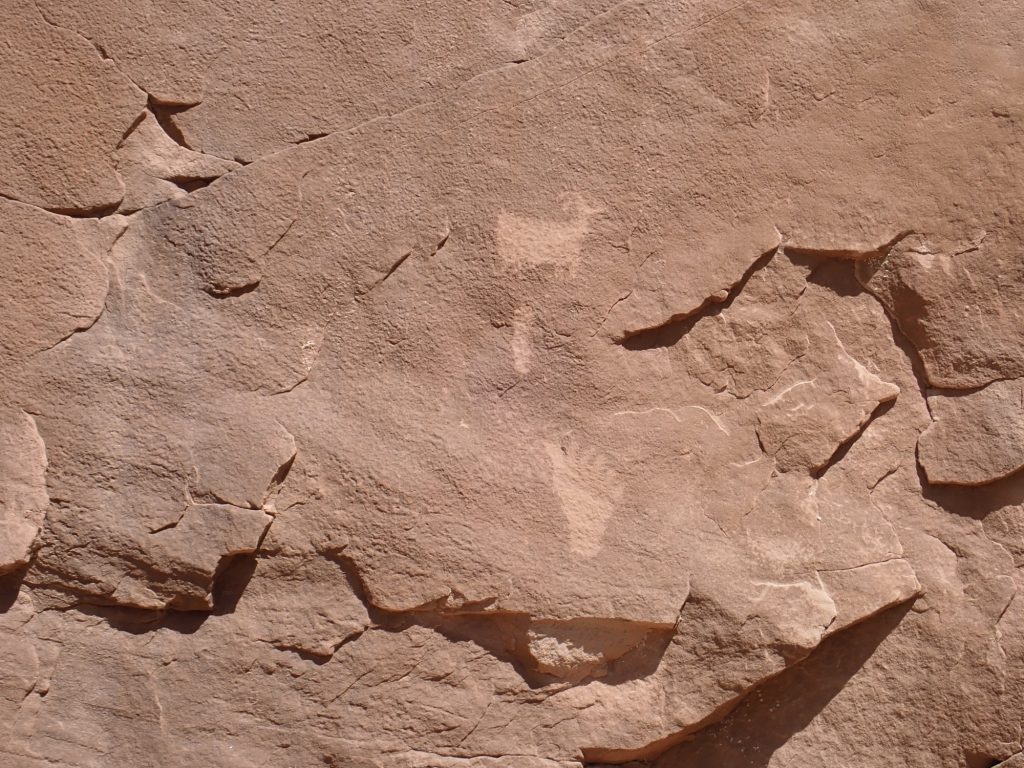

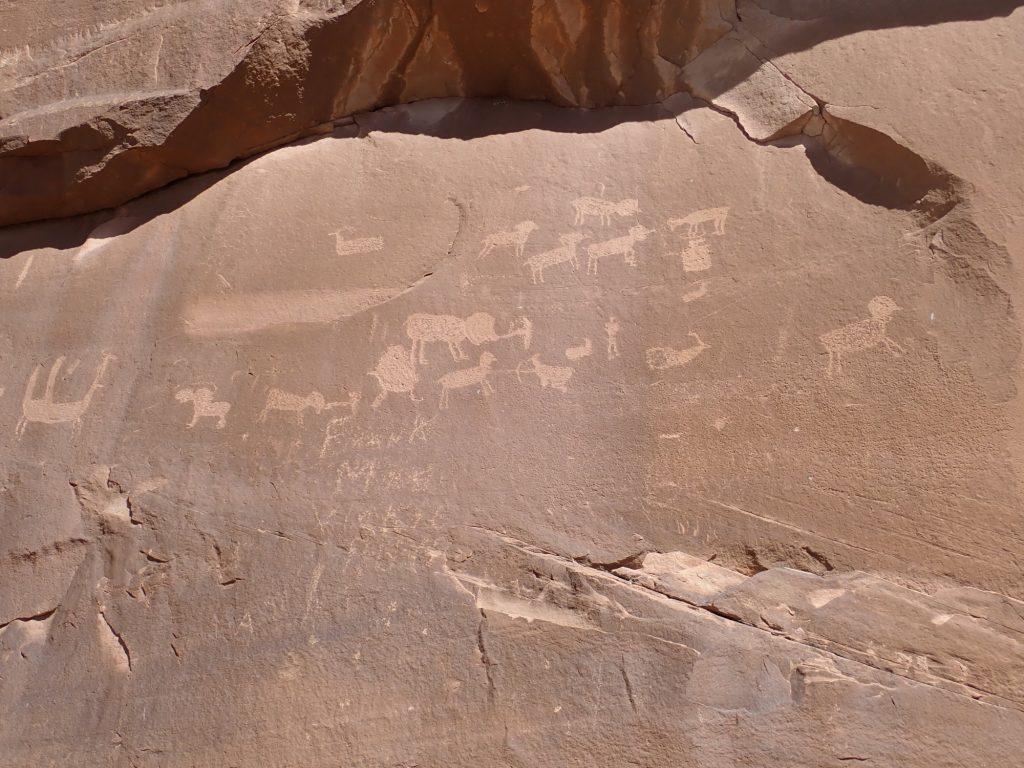

This area has numerous petroglyphs.

Conga line?

Pushmi-pullyu?

Too much desert varnish to be a modern prankster.

More dinosaur tracks.

Gary looks at the geometry of this block and convinces us that it fell from the shelf immediately behind. If so, the top surface of that shelf is the level of the tracks. I scale the shelf, but it is covered with rock debris and no further tracks are visible.

That appears to be a foot with six toes. Not impossible, I suppose.

Some depictions of hunting:

Desert wildflow.

Probably Stanleya pinnata, desert plume.

We head on to Arches and decide to hike the tail to Delicate Arch. (Indelicate Arch we skipped; this is a family blog.) The parking area, surprisingly, had spaces open. The trail passes a pioneer cabin:

Salt Wash Member of the Morrison Formation.

At left on the skyline is Entrada Formation, the usual arch-forming formation in this area. In the foreground left are younger beds of the Summerville and Morrison Formation, with a strike valley eroded out of these softer beds at center. Right of center is Cretaceous Dakota Formation, and on the far right in the distance are much older beds of Wingate Sandstone. Between is the major fault marking the crest of the Salt Valley anticline, where salt dissolution by groundwater has caused the younger beds to collapse into the crest of the anticline.

This area is mapped as Summerville Formation with occasional remnants of Curtis Formation. I don’t know which the chert is from.

The trail ascends onto slickrock of the Curtis Formation. View to the west:

I would have sworn this surface is Navajo Sandstone, but that’s not what the map says. The geology can be very confusing in this highly deformed area. We’re looking back at the parking area in the Brushy Basin Member of the Morrison Formation, with beds of Dakota Formation over Cedar Mountain Formation making up the hill to the left.

Not quite an arch.

But very likely will be someday, when the alcove erodes through the fin here. This is Entrada Formation, the chief arch-forming formation of Arches.

Very busy trail.

A very small arch, apparently named Twisted Donut Arch.

And finally, Delicate Arch.

The top is actually Curtis Formation.

There are a couple of tricks to getting a really good photograph. One obstacle is that the area is swarming with tourists

who naturally want their picture with the arch.

It sometimes takes a wait to catch the arch without people on it.

The other trick is that the arch would look best with a blue sky background, but the viewing angle is hard to achieve, due to an enormous pothole right where you’d want to stand for the photograph. This was better:

and this was better still, though it involved getting to a very precarious perch. Agggghhhh, people:

After waiting for the people to be gone.

There’s still that little blot of cloud. I don’t think I actually did much better than my first photograph.

Panorama.

You can see what I mean now about the pothole. And, why, yes, yes, that is a small bush growing atop the arch. Life is stubborn and willful.

Looking west to the Fiery Furnace area, on the skyline.

The white patchy rock is Curtis Formation; the red pinnacles are the underlying Entrada Sandstone. Yes, underlying, in the stratigraphic sense: The beds have been distorted and tilt upwards so the older rocks poke out at the crest of the ridge.

Slickrock on the hike back.

This, too, is Curtis Formation.

We get back to the car, drive in to Moab, and have dinner at a family Chinese restaurant. Greg tries to strike up a conversation but his Cantonese seems not to be the ancestral dialect of this family. The food is pretty good, though.

We cannot find a decent gas station in Moab (the place is a madhouse of tourists) and stop in Monticello instead. There is a lemonade stand across the street being run by little kids. Greg buys a glass, pronounces it good, thanks the kids, and has me stop a half mile down the road so he can toss the rest.

It’s already late and we have a long drive ahead. Chimney Rock is too good to miss, though.

Mesaverde Group over Mancos Shale.

The light fails as we drive through Farmington, and it’s a long drive in the dark back across the San Juan Basin and through the Jemez to home. I drop Gary off and we pull all his stuff out of the car. Then home for me.

No one is up. (It’s now after midnight on a Wednesday night.) Stupid the Cat blinks at me sleepily from one of the dining room chairs. I start making trips in and out to unpack. On the third trip, she’s at the door, fully awake and very glad to seem me. Yeah, she’s the one who thinks she’s a dog.

Welcome back.