Coronavirus-Restricted Excellent Adventure, Day 4

We wake to a calm morning.

Breakfast, then back up the road a couple of miles to Lake Valley. The ghost town is now a reasonably well-curated mining museum, with signage.

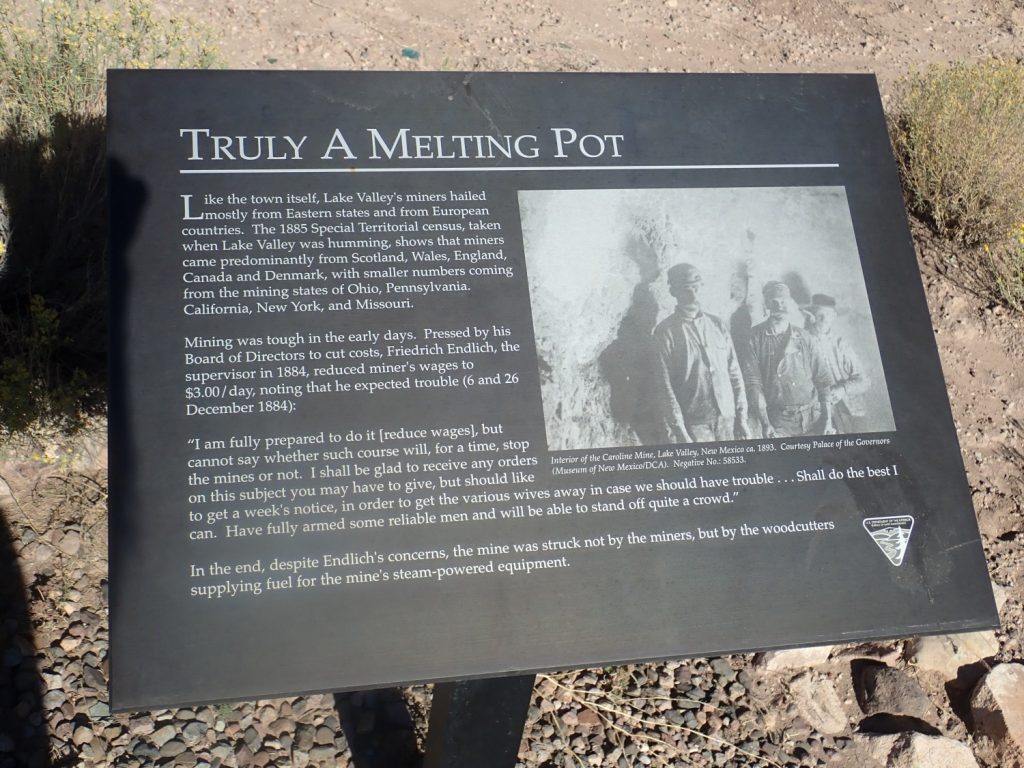

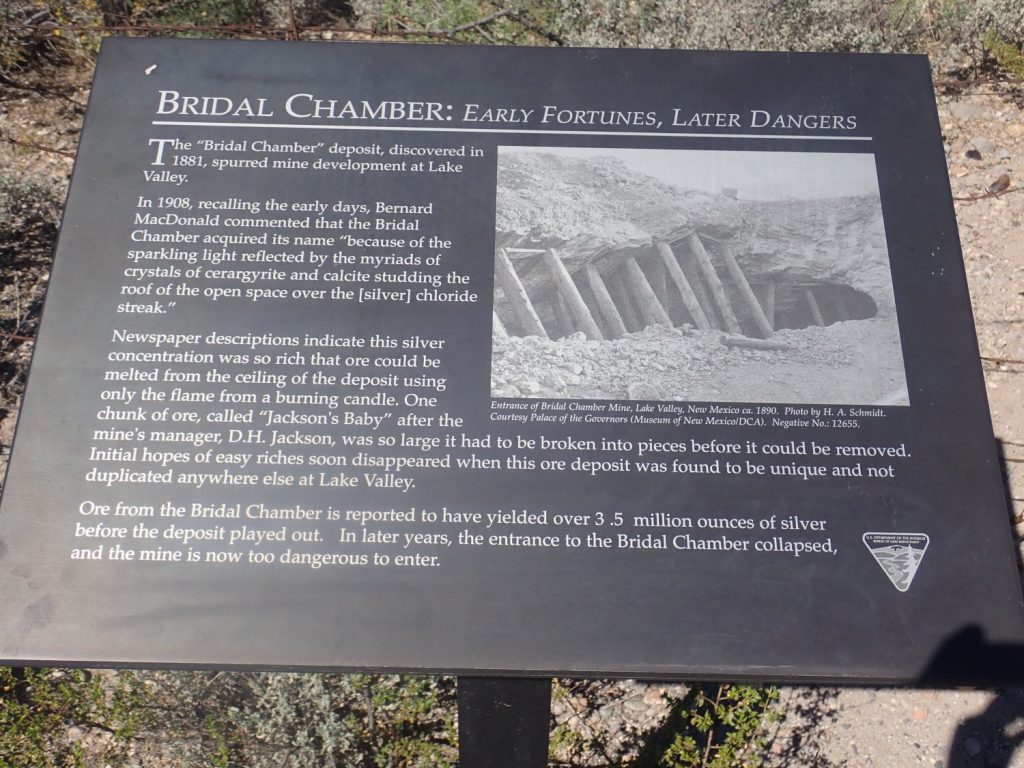

The town was more prosperous than most mining towns. There was actually quite a lot of silver in them thar hills, emplaced by hydrothermal fluids from the nearby Mogollon-Datil volcanic field that rose through ancient limestone beds of the Lake Valley Limestone, hit an overlying volcanic flow, and deposited their load of precious metals. One mine, the Bridal Chamber, was rich with unusual silver chloride ore that could be smelted with the heat of a candle. This rich strike made the mines relatively successful.

What did relative success mean? $3 a day for the miners, which was actually pretty good wages in the late 19th century. It was about three times the going wage in the town. The catch was it was all on the mining company’s books, so there was nowhere to spend it but the mining company store. You could raise a family on it, but you weren’t going to save up a nest egg for your own ranch.

What remains of the town:

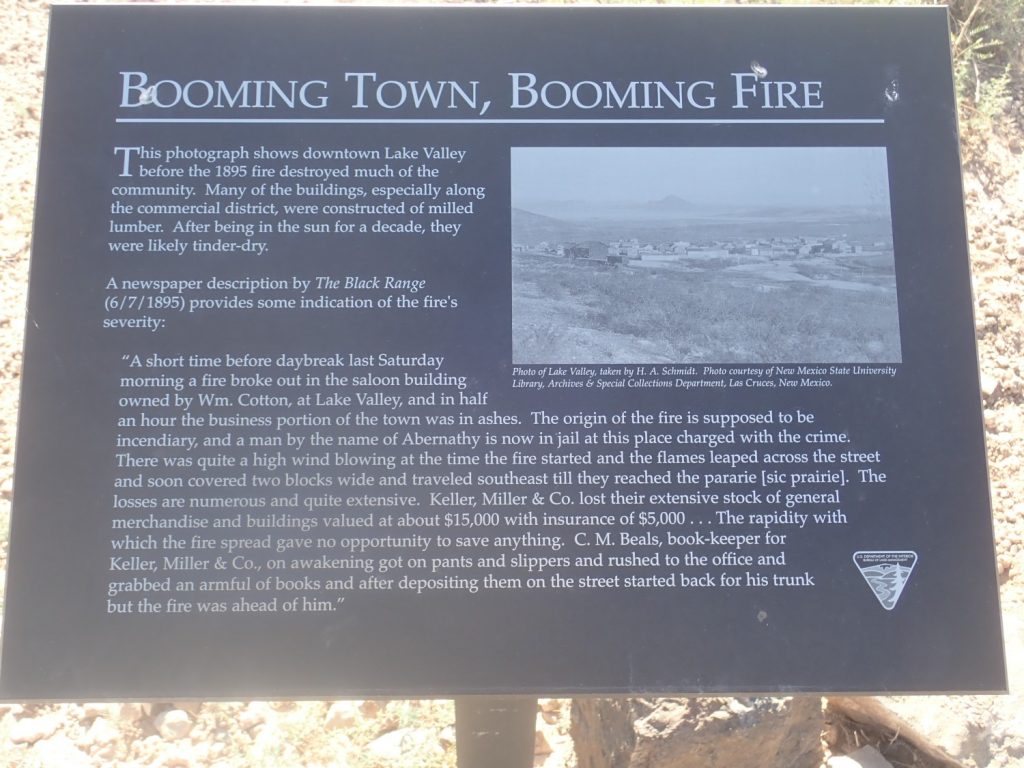

At one point most of the town was burned to the ground after a drunk set a fire in a saloon.

We enter the museum just in time to meet the curator. He’s a volunteer but seems good at what he does. The museum had opened from COVID closure just two days before; our timing was perfect.

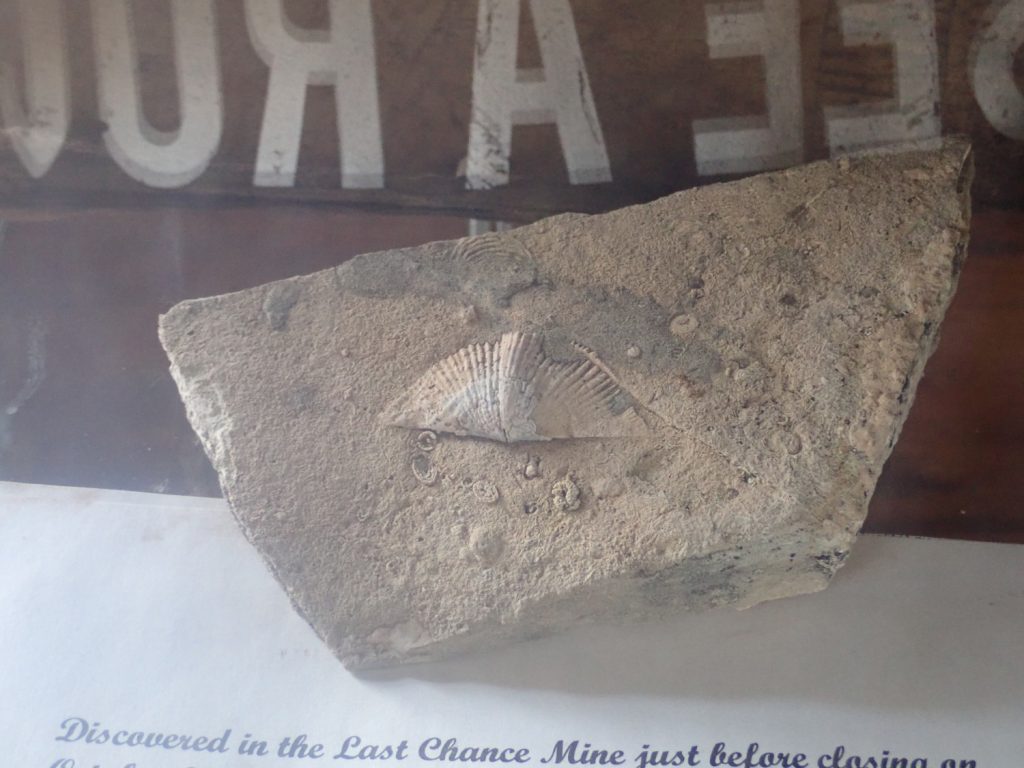

There is a nice brachiopod fossil in the display cabinets, which seems promising.

The curator tells us he actually met the (by then very old) boy who first carved up this desk in the schoolroom/chapel.

Gary has a long conversation with the curator.

The old organ

and piano.

The curator tells us that the fire did not put the town out of business. He did extensive research but never found out what happened to the suspected arsonist. The suspect was arrested and sent to Hillsboro, the county seat, but there is no record of the disposition of the case. He was probably not lynched; there are accounts of townsfolk saying that he was a pretty decent guy when he wasn’t drunk. We also get directions to some possible fossil sites.

The Bridal Chamber:

Unfortunately for the town, no other deposit in the area ever came near to being as remarkable as this one.

This outcrop turns out to be mostly devoid of fossils. Just a few bryozoan fronds.

We head for a side road the curator suggested to us, turn too soon, and it turns out to be a very fortunate error: We find ourselves at the base of a Mississippian fossil reef.

Or so I thought.

I thought this was limestone with algal layers — a fossil bioherm — and the entire hill above us was a huge algal reef.

We started climbing up. Life was abundant.

We start seeing more of what I’m mistaking for limestone layers deposited by algae.

I should really have figured it out by the time we reached the top.

If this was a reef, where where the body fossils? I rationalized that this was a reef that formed in the kind of salty, hot water stromatolites form in today, where little but the algae can survive.

No. According to the geologic map, this is the eroded heart of a ring fracture dome of the giant Emory caldera, erupted some 34.9 million years ago. We’re looking at spectacularly flow-banded rhyolite of the Mimbres Formation, not algae-deposited limestone of the Lake Valley Limestone.

Maybe if I can’t tell a rhyolite from a limestone, I should just pack it in now. Then again, I didn’t bring the bottle of hydrochloric acid to test rock for carbonates; we would be dropping no acid on this trip. And we were on a road where we were told there were excellent fossil beds, in an area where the limestone is known for its bioherms (fossil reef mounds). We were seeing exactly what we expected to see.

And this is what a stromatolite, one form of algal mound, looks like:

You have to admit that there is some resemblance.

That said, this is still a pretty cool part of the Lake Valley story. The Emory caldera was huge; much larger than the Valles caldera. The rock here solidified from residual magma from the big caldera eruption, which oozed out of the ring fracture where the caldera had collapsed. The magma was the source of the metal-rich hydrothermal fluids that deposited silver ore at Lake Valley just to the east.

By now we realize we’ve taken the wrong side road for hunting fossils. We head north and find the right one. Across the road is a ridge of interesting rock.

This looks to me like some very ancient metamorphosed rock, perhaps a Precambrian quartzite metamorphosed from a breccia.

We continue up the ridge and find more of the same. It really does look like a quartzite. I’m not so far off this time; this area turns out to be named Quartzite Ridge, and the rock here is Fusselman Dolomite that the map indicates has been locally silicified. No fossils, alas.

Further on we come across some Fusselman Formation that has not been silicified.

Here the dolomite has a characteristic weathered look, called karst texture, that indicates the rock was exposed and eroded before being buried again in the sediments that became the Percha Shale.

Wildflower.

Almost certainly evening primrose family, possibly Clarkia rubicunda.

The Lake Valley area seen from the top of the ridge.

We’re not going to find fossils in this dolomite. We are returning to the car when we see that the car appears to be rolling backwards down the road to the highway. Snow. We look more closely and decide it’s not Gary’s car after all. And it appears to be under a driver’s control. But we do not breathe easy until we finally are able to see around a clump of trees that Gary’s car is still there.

Road cut further up the road.

The map identifies this as El Paso Formation, an Ordovician formation. The map says it’s fossil-bearing, but we find none here.

The next couple of road cuts are also unpromising. We give up when we hit a cut that is clearly volcanic.

More Rubio Peak Formation.

We head to our final fossil hunting ground, Apache Peak:

It’s a steep climb, but multiple sources indicate there are fossils here. The slope is steep and this makes it hard to match up with the geologic map, but the lower slopes are poorly exposed Percha Shale; the thin ledge at right may be Caballero Formation; the thick ledge above would then be the base of the Alamagordo Member of the Lake Valley Limestone.

I find my first fossils: Crinoid stem segments and bryozoans.

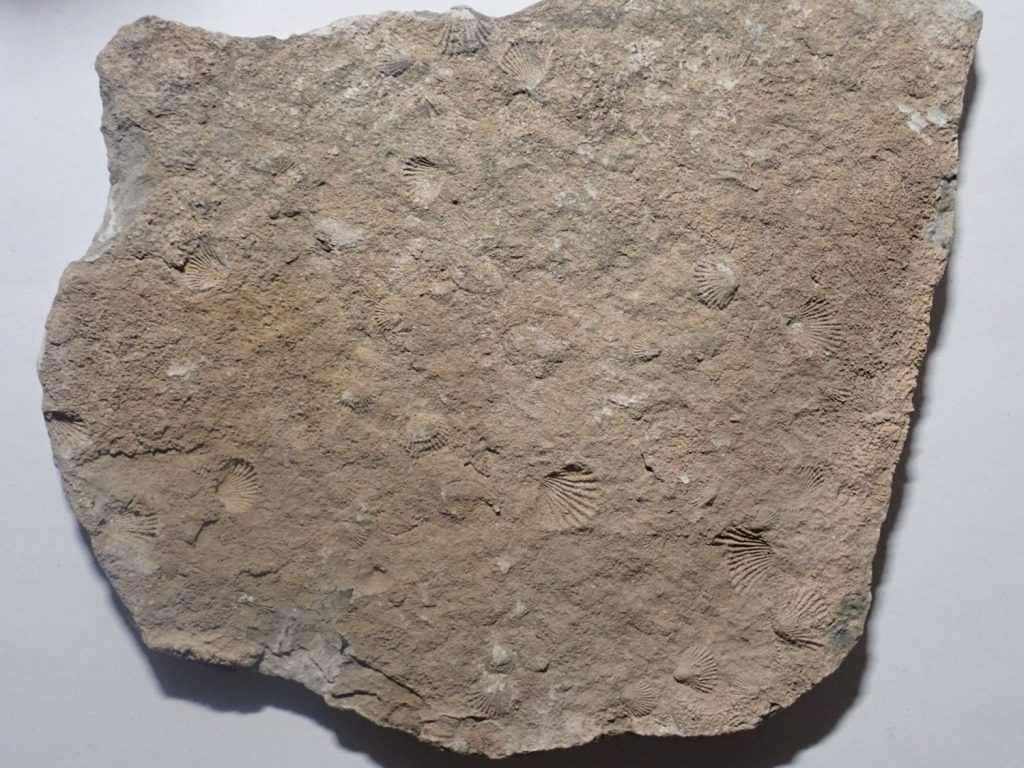

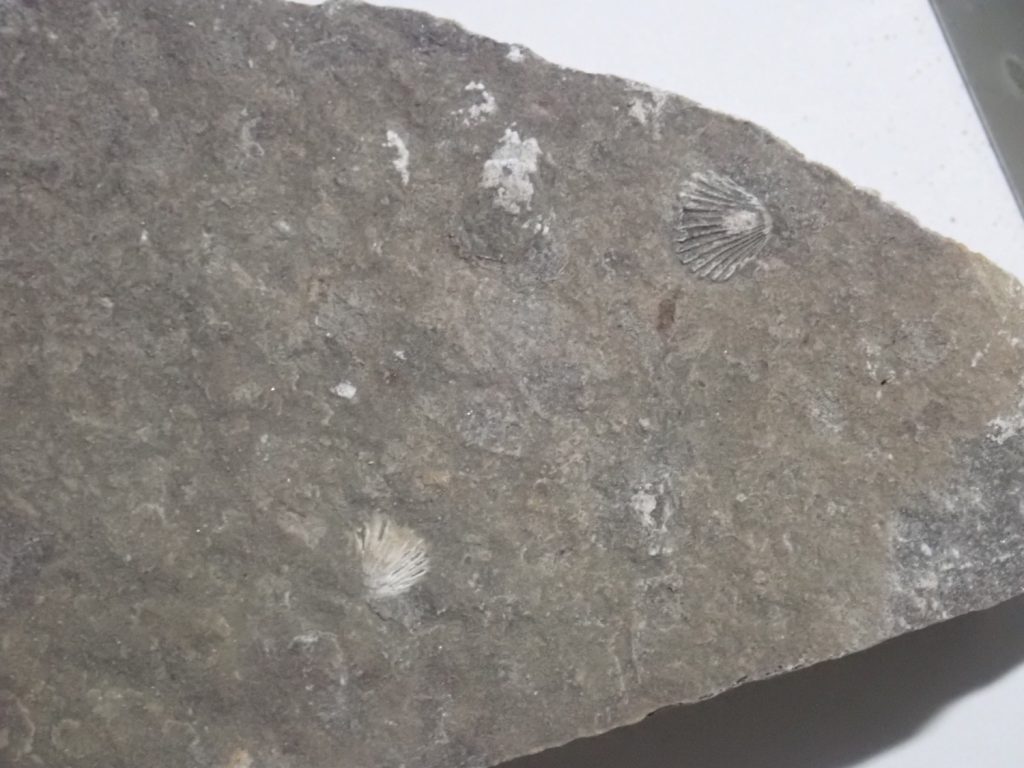

Gary finds a solid outcrop, probably in the Caballero Formation, that is thin and platy. He hammers off a few plates, and sure enough. We are soon hammering away and get some find specimens of a beautifully delicate … brachiopod? All the same species.

This image shows reverse casts.

while this seems to show the fossilized shells themselves.

I’m not paleontologist enough to identify the species; I do well to nail the phylum. But these are about a half inch across and in Mississippian beds. Perhaps Cupularostrum? Or Eumetria? Based on Googling “small Mississippian brachiopod” and seeing what came up that looked close.

The top plate could be instantly destroyed by carelessly placing anothe rock on top. I’ll have to ask the folks at the Los Alamos Geological Society for suggestions on preserving this fossil plate. I fear that even rinsing it in water might destroy the casts.

We head south. Our original plan was to drive way into the New Mexico boot heel to look at a Cretaceous fossil reef, but decided a reef in hand is worth two in the bush. We skip the boot heel and head to Rock Hound State Park to camp for the night.

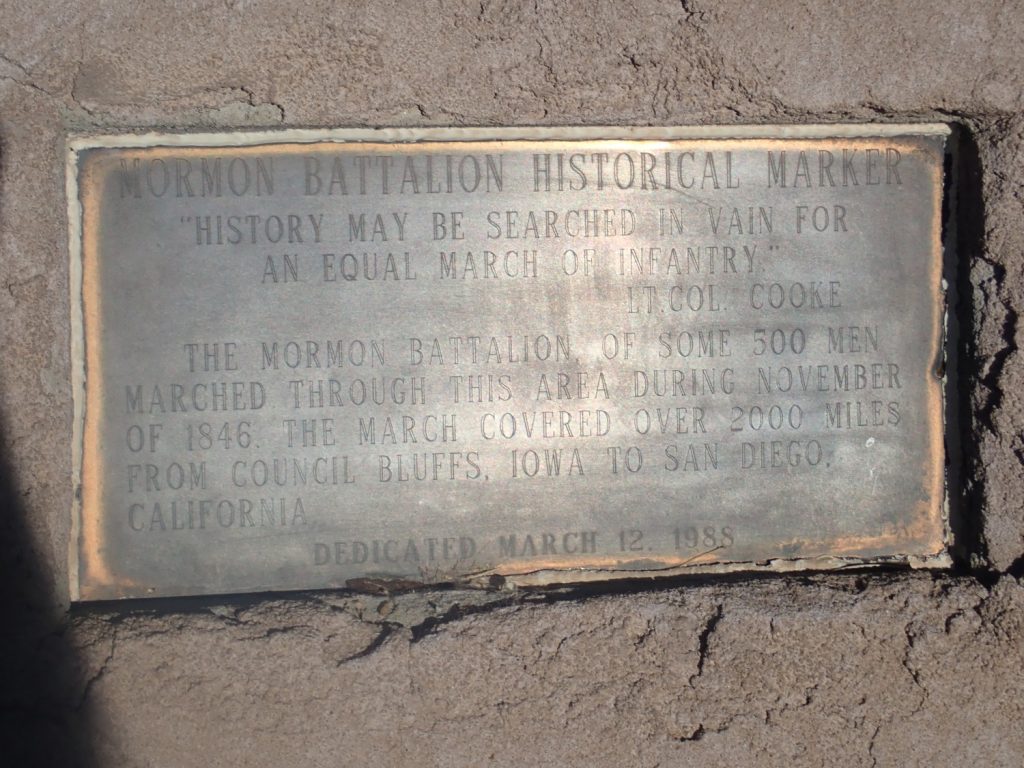

Along the way, I spot a small pyramid by the side of the road, and we get some history.

I learn that Cooke’s Range is named for the commanding officer of the Mormon Battalion.

A small and quite young cinder cone.

One almost expects a giant ant to emerge from the top and go scurrying off to terrorize Joan Weldon.

We refuel in Deming and drive to the state park. There is a sign saying “All electrical units reserved”. There is another, which I don’t think Gary sees, which says “Campground full.” It is partially obscured and I’m not sure if it is actually meant to be out there. Regardless, Gary pays the $10 at the self-pay box and we drive in. Sure enough, the area labeled “Non-electrical campsites” is empty. We start to unpack.

The host comes up. “This area is closed. Covid.” There are no open camp sites. Gary is quite unhappy, but what can one do? We need to find some BLM land to camp on. The camp host doesn’t know where any is. We find a spot way out of the way, but it’s rocky and covered with cow droppings and just doesn’t feel right. (Turns out, when I look at the jurisdiction map after getting home, that it’s on private land, too.) I give Gary the BLM jurisdiction map URL and he Googles it up. We find another spot across a bad gully that looks like no one owns it and and find some acceptable flat ground; we set up and camp.

Turns out we were right on the boundary between private and state land. Good enough; no one comes out to chase us away and we spend the night.

Next: Fried chicken and a pair of maars

Can I join your site?