The wanderlust, it is upon me

Sometimes when I want to clear my head, a long walk is good. I’ve also taken an interest in local geology lately. So I decided last Monday to take a hike in the hills northwest of Los Alamos, in the head of Rendija Canyon behind LA Mountain. There’s a trail called the Mitchell Trail that is supposed to be good.

So after writing down for Cindy exactly where I planned to go and for how long, and slathering myself with sunscreen, and packing up a couple of water bottles and an orange and a camera and binoculars and a borrowed cell phone (I don’t own my own; taking one accidentally to work would result in an unpleasant character-building experience) I headed out, found the trail head, and started hiking.

The trail was very clear at first, but recent forest fires have made the trails a lot less obvious in places. Finally the trail went down into a large gully and just disappeared. No sign of it on the other side.

Well, shucks.

Went back home. Looked on Google Earth. Discovered I’d let myself be diverted onto a utility road that did, indeed, look like an excellent trail, but really did end in the middle of nowhere.

So yesterday I headed out again with a clearer idea where I was going. This time I didn’t turn the wrong way, and I got some nice pictures.

Poprphyritic rhyodacite boulder of the Rendija Canyon Member, Tshicoma Formation, Polvadera Group, showing flow banding and plagioclase phenocrysts. Quarter provides scale.

(Hey, this whole hike was an exercise in geekiness.)

The Tschicoma Formation is about 12 to 3 million years old and makes up most of the skyline west of Los Alamos. It’s mostly dacitic to rhyolitic in composition, meaning it’s moderately to highly enriched in silicon. Its most distinctive feature is that it almost always has large crystals of sanidine feldspars embedded in a fine grained bright red to light gray matrix.

The Rendija Member is one of the older members of this formation, dating back about 7 million years. The younger peaks west of Los Alamos (in the Sierra de los Valles), such as Caballo Peak, Tschicoma Peak, and Pajarito Mountain, go back about 3 or 4 million years. With the forest cover removed by recent forest fires, it does look a lot like the younger peaks are draped over more heavily eroded older lava flows.

Daisy in a boulder.

I am no Ansel Adams, but this’ll do, this will do…

The locally notorious Guaje Ridge rock window.

This is reached via a rather steep and rocky side trail best climbed with occasional three-point contact. I managed to wrench my left knee pretty good making the climb, but I got all the way to the window.

It would seem I am no longer 30.

Town site from the window. Yes, that’s the Arizona Street water tank, which (if you were interested) is cut into a bank of welded rhyolite tuff of the Tsherige Member, Bandelier Formation, Tewa Group.

The Bandelier Formation makes up the characteristic pink finger mesas found all over Los Alamos and the Jemez. These were laid down in two separate eruptions, 1.6 and 1.2 million years ago, and the Tsherige Member is the more recent eruption. Geology in Los Alamos mostly consists of climbing down into canyons to see what’s under the Bandelier Formation or climbing up mountains to see what sticks up above it.

Looking south from the rock window towards Pajarito Mountain (which just pokes above the nearer ridges)

Looking west from the rock window towards Rendija Mountain. Unless it’s Quemazon Mountain. Both names are used; neither is official.

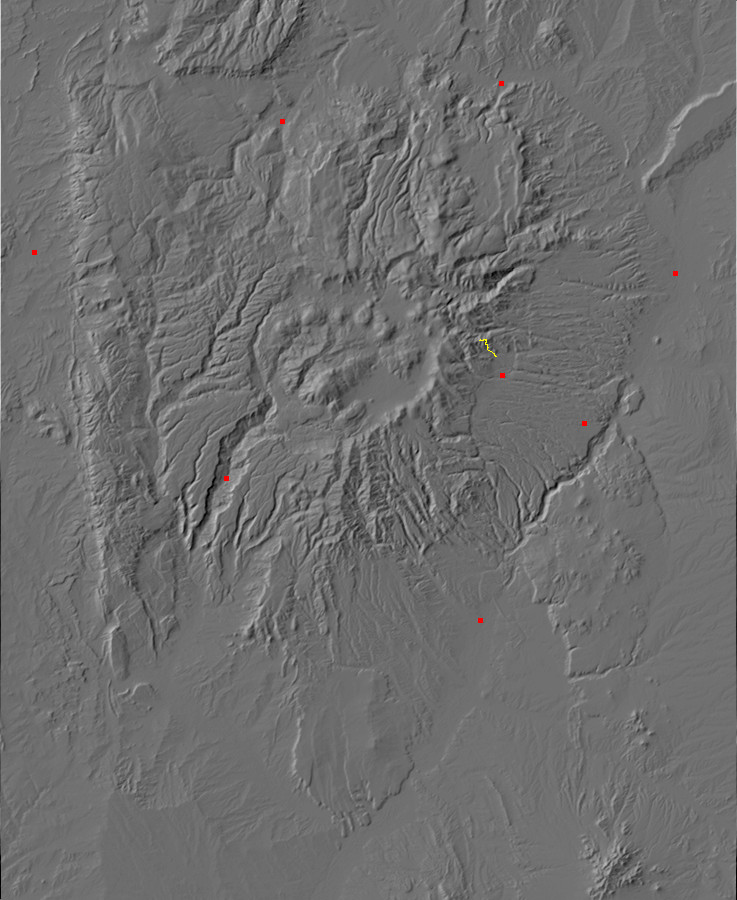

Geologists tell us Guaje Ridge is a massive dacite flow from a single eruptive center to the west; possibly Quemazon Mountain, possibly a vent even further west that foundered into the caldera when Valles Caldera was formed by the same eruptions that produced the Bandelier Tuff.

Dacite is a kind of fine-grained volcanic rock with moderate amounts of silica in it. Lava with more silica forms rhyolite; lava with less silica forms andesite or basalt. Basalt is the black rock that lies underneath most of White Rock. More precisely, the black rock underlying White Rock is tholeiitic basalt, low in sodium and potassium.

Dacite cliffs showing surge beds.

Guaje Canyon looking towards Black Mesa.

Looking down the trail.

Scoria boulder way up on the ridge.

Scoria forms from lava that is all frothy from dissolved gases that form bubbles.

Dacite outcropping with what looks like cross bedding.

Except that cross bedding is normally a feature of fossilized sand dunes, and this is a lava flow. Go figure.

Flow banding in rhyodacite outcropping.

Hope you like the pictures.

My knee is sufficiently wrenched from climbing to the rock window that the next hike won’t be for a couple of weeks, and it will be rather easier. Should have some more interesting geology, though.

Copyright ©2014 Kent G. Budge. All rights reserved.

Hi. i’m Kieron and I like geology too . And i like to hike.