Wanderlusting Cerro La Jara

But first, the usual word from our sponsor:

So I had hoped to hike across Banco Bonito to El Cajete. Banco Bonito is a big obsidian flow that is thought to be the youngest volcanic flow in the Jemez. El Cajete is the crater it came from. Unfortunately, I was told the area is not presently open for hikers; free fire zone. I’ll explain later.

But while I was at the Valles visitors’ center, I bought a map and got talked into taking the short hike around Cerro La Jara. This is a small volcanic dome kind of by itself out on the caldera floor, close to the visitors center, and hiking around it takes an hour if you explore a little on the way. It made a nice backup plan.

First, the view from the visitor’s center:

That’s Cerro La Jara in the background. It may not look like much, but that’s because you don’t realize until you get up close that the trees are huge.

One more shot from the parking lot first:

This is looking southeast across the Valle towards the caldera rim.

The trail crosses the caldera floor, which is infested with badger burrows. I didn’t think to take a picture. Think gopher on very effective steroids.

Cerro La Jara formed from very high-silica lava that oozed out of the fault line where the caldera collapsed long after the collapse. Whereas the caldera collapse was 1.2 million years ago, Cerro La Jara is only about half a million years old. The high silica lava from which it formed is extremely viscous and can only flow a short distance from the vent before hardening to form a light volcanic rock called rhyolite:

Here you see some rhyolite boulders on the slope of the dome. The layers of lava are clearly visible under all the lichen. This kind of surprised me; I didn’t think rhyolitic lava flowed even enough to form layers like this. But apparently such flow banding is a frequent feature of rhyolite flows.

A view back to the visitor’s center from atop that knoll, showing larger lava domes inside the north rim of the caldera:

You can’t actually see the north rim. The mountains here are all domes within the caldera, which are larger versions of the one I’m standing on for this photo.

Here is a close up of the rhyolite, with Mr. Quarter for scale:

It looks a lot like Bandelier Tuff, which is not surprising given that the composition is almost the same. However, rhyolite is much harder, since it formed from liquid lava rather than from a cloud of partially solidified lava fragments.

Here is an interesting exposure:

The harder lawyers likely formed from flows of liquid lava, while the softer, more easily eroded layers in between likely formed from rhyolite ash falls, something like tuff.

Here’s some boulders sticking up above the southern side of the dome:

It’s interesting that the layers in the rock almost match the slope of the ground.

This shot shows an eroded cliff face on the south side of the dome:

You can see the many layers of flows and their inclination around a central axis.

The amenities:

This hike was kind of a unique experience in that I was not only not told to stay on the trail, but was actually encouraged to avoid any kind of trail. They’ don’t want a beaten path here. On the down side, this meant some stickers in my socks. People being how they are, you can see that a faint trail is starting to be beaten into the grass at the left.

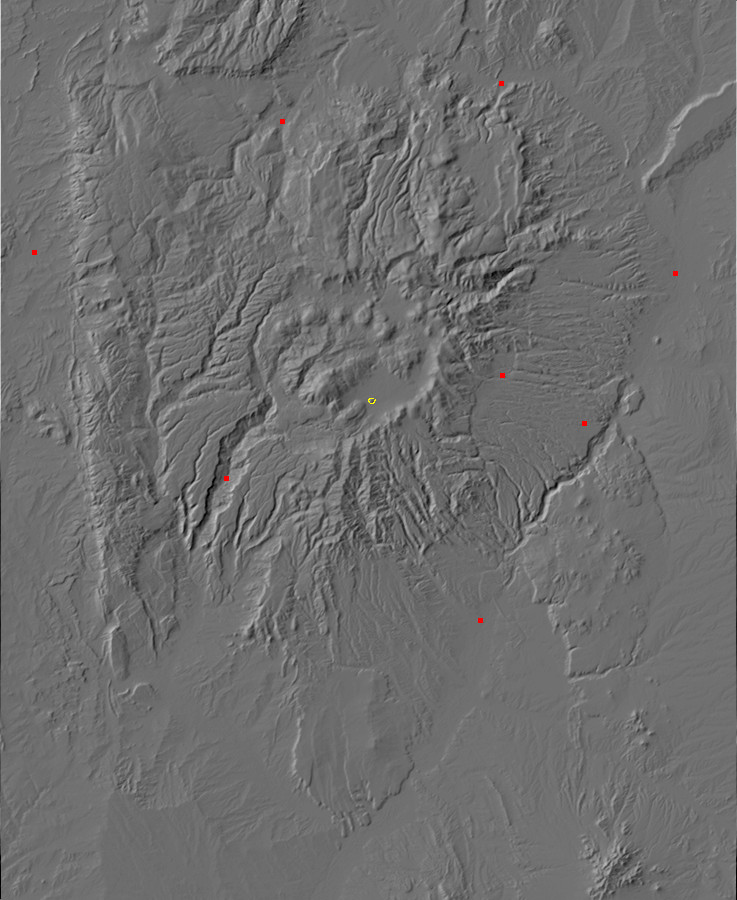

Looking southwest from the table:

The central peak is Redondo Peak, the type example of what geologists call a resurgent dome. It’s where the caldera floor has been forced back up by fresh magma moving into the magma chamber beneath. The little knob to the right is Rendondito. The nearer mountain to the left is South Mountain, which I would like to have explored, but was advised not to, because it was apparently a free fire zone this weekend — it was Gun Nut Weekend in that part of the caldera (I don’t think that was actually the official name but it conveys the idea.)

North side of the dome showing that the winter snow has just begun to accumulate:

I’m not sure what kind of trees those are, but they have branches covered with single, fairly short needles, and they’re huge. Douglas-fir, if I’m not mistaken.

This is kind of interesting:

This is a spot on the north side of the dome, with Mr. Quarter for scale, showing chips of obsidian on the ground. Now, obsidian and rhyolite form from the same kind of of lava, but these are isolated chips; the bedrock here is all rhyolite, not obsidian, and obsidian doesn’t often survive for half a million years anyway. My guess is this is an archaeological site.

View from the crest line just above the obsidian patch, looking back to the south:

And one more. Mr. Quarter in a patch of very coarse moss. I don’t recall seeing moss this coarse before:

Copyright ©2013 Kent G. Budge. All rights reserved.