Wanderlusting Abiquiu

It’s been a gorgeous autumn, and I’m finding myself very much disinclined to waste any of it. So I took my Monday off to go see some rift fill.

My home is perched on a plateau in the Rio Grande Rift, a zone reaching from Colorado to Texas where the earth’s crust has been wrenched apart over the last thirty million years or so. It’s part of the more general wrenching apart of the western United States brought about by North American wandering onto the East Pacific Rise, an area where mantle rock is slowly deforming upwards towards the surface.

The rifting process is gradual enough that the Rift has filled with sediments as it has been pulled apart. These rift fill sediments underly most of the Rio Grande River valley (which is more or less the visible surface expression of the Rio Grande Rift) and have been lumped together by geologists as the Santa Fe Group. And the oldest of these rift fill sediments in the Jemez area are the El Rito Formation, the Ritito Conglomerate, and the Abiquiu Formation.

So I packed a lunch, gassed up Clownie the Wonder Car, grabbed my GPS and rock hammer and other geology gear, and headed out from White Rock through Espanola towards Abiquiu. The first part of the route is familiar ground. Cindy and I drive to Espanola every couple of weeks for groceries:

Whatever happens, they have got

A Wall-Mart store, and we have not.

I still marvel at the amazing geology every time we drive down there, but I’ll save it for another time.

North of Espanola, in the Medanales area, I switched into geologist mode and took my first photograph of the day.

Sierra Negra. Looking north from 36 12.231N 106 14.805W

This is Sierra Negra, which is prominent to the northeast from Abiquiu. The mountain is capped with a basalt flow that erupted not quite five million years ago. This has preserved the softer sediments underneath, so that subsequent erosion has produced a mountain by leveling everything else around it. This is an example of what geologists call inverted topography: Lava tends to pool in valleys and other low areas, and erosion then turns the low spots into high spots.

My interest in Sierra Negra today is that there is a major fault running right through the mountain. This fault is part of the Rio Grande Rift, and it has thrown down younger beds of the Chama-El Rito Member of the Tesuque Formation, on the right, so that they lie alongside older beds of the Abiquiu Formation on the left. The Chama-El Rito Member is mostly river deposits from the ancestral Rio Chama and it has a pinkish color. The Abiquiu Formation is mostly reworked ash beds from eruptions in the San Juan Mountains 25 million years ago and it has a distinctive whitish color.

From there I proceeded to Abiquiu. I was intent on visiting a spot called Plaza Blanca, reputedly much loved by painter Georgia O’Keefe, that is just visible from the Abiquiu highway as white cliffs to the north. It is obvious on Google Maps and is reputed to be one of the most spectacular exposures of the Abiquiu Formation.

Getting there turned out to be more difficult than I expected, or that it needed to be. I had glanced quickly at Google Maps, saw that there was a road in that also served a mosque (suggesting the road would be reasonably passable) and did not really fix in my brain just where this road left the highway. So I wandered around the area north of the highway and south of the Rio Chama for some time before doing what guys reputedly never do, namely, ask for directions at the local store.

Which I got, though the young clerk giving me directions had a certain air of not planning to make a career of the tourism industry. Apparently Plaza Blanca is not that uncommon a tourist destination.

Or maybe she had just had enough of wedding parties that day. Apparently there were several taking place in the area.

The road I was looking for branches off the highway not far past the Abiquiu bridge and curves back to the northeast. It turned to be a gravel road, but a good one, which soon turned back into pavement. The road went past Cerrito Blanco.

Cerrito Blanco. 36 12.988N 106 19.368W

Cerrito Blanco is an excellent example of a sedimentary dike. It lies along a major fault, where ground water was able to move freely and deposit minerals in the normally soft sediments of the Ojo Caliente Sandstone of the Tesuque Formation. The softer sediments nearby have since eroded away, leaving this feature.

The road soon reached the turnoff to the mosque and to Plaza Blanca. It turns out the mosque owns the entire Plaza Blanca area, but is generous about permitting visitors, though the road is closed past a small parking area and you have to hike the rest of the way. Which is entirely reasonable.

The view from the north edge of the parking area was promising.

Plaza Blanca parking area. 36 13.943N 106 18.203W

That’s Sierra Negra peeking over the ridge in the last frame.

About this time a herd (flock? college?) of young people arrived, with that je ne sais quoi that screams “college students on break”, though they might possibly have been a geology or art class. (No professorial types obviously present, though they get harder to pick out the older I get.) We all passed the gate and hiked on down to see things closer up.

The pile of gravel here marks an ancient side channel of the Rio Chama River.

Side channel gravels. 36 13.981N 106 18.150W

A couple more turns, and we get to the spectacular stuff.

Abiquiu Formation at Plaza Blanca Canyon. 36 14.048N 106 18.180W

As I mentioned earlier, the Abiquiu Formation is mostly beds of reworked ash from eruptions in the San Juan Mountains 25 million years ago. The ash was deposited further north and was washed down into the Rio Grande Rift, which was still quite young at the time. The darker bed in the cliffs in third and fourth frames contains numerous clasts and may mark an ancient stream bed.

Another view, including the herd:

Abiquiu Formation at Plaza Blanca Canyon. 36 14.048N 106 18.180W

Abiquiu Formation at Plaza Blanca Canyon. 36 14.048N 106 18.180W

And a close up of the best bit of cliff:

Abiquiu Formation at Plaza Blanca Canyon. 36 14.048N 106 18.180W

Looking west, I saw some mystery beds:

Abiquiu Formation at Plaza Blanca Canyon. 36 14.048N 106 18.180W

Yeah. The reddish beds caught my eye. I don’t actually know what those are. And, as a guest of the local mosque, I wasn’t eager to go hammering off pieces for examination.

This at least I recognized. This is the Cerrito de la Ventana dike:

Abiquiu Formation at Plaza Blanca Canyon. 36 14.048N 106 18.180W

The dike is the dark cliff behind the white Abiquiu Formation cliffs. With a radioisotope age of about 20 million years, this dike intruded through the Abiquiu Formation not long (in geological terms) after it was laid down. It is an example of pre-Jemez volcanism in the area.

As I was driving out, I spotted some peculiar-looking rocks and snapped a photo.

Remnants of tuff ring. Looking northeast from 36 13.361N 106 17.845W

According to the geological map of this area, the greenish-tan beds at left and right center in the photograph are remnants of an old tuff ring formed by localized volcanic activity within the Chama-El Rito Member. The tuff ring has not been dated. Probably on private land, so I couldn’t get a closer look.

I pulled back onto the highway and went looking for Ritito Conglomerate. It wasn’t hard to find.

Ritito Conglomerate in road cut west of Abiquiu. 36 13.855N 106 22.846W

As you drive west from Abiquiu, you encounter older and older rocks as you climb the west side of the Rio Grande Rift. The Ritito Conglomerate is the next layer down from the Abiquiu Formation, and it is described in older papers as the lower Abiquiu Formation. (This means that older papers describe what I’ve been calling the Abiquiu Formation as the upper Abiquiu Formation. I get the impression sometimes that geologists love to argue over formation names.) The Ritito Conglomerate is basically a pile of mud, sand, and pebbles, probably laid down in a river valley, with some volcanic ash from eruptions in the area north of Taos. However, it does not have nearly as much ash as the Abiquiu Formation, and so, while it is fairly light in color, it’s not the very pale white of the Abiquiu Formation.

Well, cool. Next stop was the village of Canones and the El Rito Formation.

Canones is one of those charming little northern New Mexico villages of which it is said that, while it’s not the ends of the earth, you can see them from there. Naturally I encountered several elderly artists in the area out with their easels.

And the highway cuts into the El Rito Formation.

El Rito Formation. 36 11.369N 106 26.796W

The El Rito Formation is the next layer down from the Ritito Conglomerate. Its age is a bit uncertain, because it contains few fossils, but may be around 50 to 30 million years old. It’s also the oldest formation that can reasonably be interpreted as Rio Grande Rift fill sediments. Here’s a sample.

El Rito Formation. 36 13.920N 106 23.018W

This sample is a medium sandstone of well-rounded but poorly-sorted quartz grains with some feldspar and a few lithics and a fair amount of reddish cement in the pore spaces. A distinctive feature is the presence of muscovite mica flakes, generally aligned with the bedding planes of the sandstone. You don’t often see mica flakes in a sandstone.

And the Ritito Conglomerate is sitting right on top of these beds, just like it should be:

Ritito Conglomreate north of Canones. 36 11.369N 106 26.796W

I wasn’t entirely satisfied with that exposure of El Rito Formation, which was just kind of peeking out from under the Ritito Conglomerate. So I started hiking down the old road, which parallels the modern road into Canones, and which is truly a wonderland of potholes. Nothing wrong with it as a hiking trail, though, and the road cut rewarded me with a much better exposure of the El Rito Formation.

El Rito Formation. 36 13.920N 106 23.018W

This looks rather like river channel deposits to my admittedly not fully trained eye.

Back up the road and into the village. My intention was to find the road south to Pueblo Mesa, which features both some nice Bandelier Tuff exposures and the ruins of an Anasazi pueblo. However, the village turned out to be a maze of twisty little streets, all alike, and I probably circled the church a couple of times before finding the bridge across the creek. You’d think it would not be possible to get lost in a little village like this one. (Evil Kent: “But you’re smart enough to be amazingly dumb that way.”)

Once across the bridge, I made the logical mistake of turning south instead of north (the mesa was to the south) and wound up here. My road log warned that the road to the mesa was bad, but really. After stumbling around in boggy ground and encountering a barbed wire fence, I gave up, not realizing until I got home where I’d made a wrong turn and missed the right road. Well, that just gives me a reason to come back someday.

On the way out, I spotted several elderly artists painting away. Turns out the cliffs south of Canones have some spectacular exposures of Abiquiu Formation. Which I did not photograph, reasoning that they’d be better if I came out again earlier in the morning. (By now it was afternoon.)

On the way back to the highway, I spotted the really good exposure of El Rito Formation, which alas was across private land:

El Rito Formation. Looking north from 36 11.271N 106 26.738W

Still made a nice photograph.

Then up Forest Road 100 to see some more exposures of these three formations in the northern Jemez. These are best seen around Temolime Canyon, south of Cerro Pedernal. Here’s the Ritito Conglomerate again, in the road cut just south of the canyon:

Ritito Formation. 36 08.342N 106 30.784W

Some exposures of the Ritito Conglomerate in this area contain large clasts of Amalia Tuff at the top of the formation, but I found none here. The clasts were all quartzite, gneiss, and other Precambrian rocks likely weathered from the Tusas Mountains.

The Pedernal Chert is particularly well exposed here, forming a prominent ledge separating the Ritito Conglomerate and Abiquiu Formation:

Pedernal Chert forming the prominent ledge. Looking north from 36 08.418N 106 30.630W

It’s a bit of a scramble to reach the ledge, beneath which are unusually well cemented beds of Ritito Conglomerate. Here’s the chert layer close up.

Pedernal Chert. Car keys for scale. 36 08.486N 106 30.622W

The Pedernal Chert is a bed of amorphous silica and limestone. The limestone probably formed as a calcium-rich soil under arid conditions atop the Ritito Conglomerate. Later, the Abiquiu Formation was deposited on top of the limestone layer, and groundwater circulating through the ash-rich Abiquiu Formation picked up silica that was redeposited in the limestone layer. (Deposition of amorphous silica in limestone beds is very common, though the chemistry seem not to be fully understood.) Large clasts of chert can be found around the base of Cerro Pedernal, where it was exploited by early native Americans. The chert varies in color from milky white to pitch black.

I ended up with a lot of seed pods in my socks by the time I got back to my car, but it was probably worth it.

My geological map shows that there are beds of El Rito Formation beneath the Ritito Conglomerate here, but warns that the exposures are “poor”. This is not quite the same as “exists only in some geologist’s imagination”, but pretty close:

El Rito Formation. 36 08.616N 106 31.070W

Yeah. The red dirt and occasional red bit of rock are El Rito Formation, almost buried under basalt debris from Cerro Pedernal. Similar poor exposures continue west and south as far as upper Coyote Canyon.

During my scrambling around looking at rocks, a ginormous truck came by with an older northern New Mexican behind the wheel. He enquired as to whether I was all right. I answered “Yes” but I suppose it depends on how you take the question. It’s touching how people seem to look out for each other up in the hills.

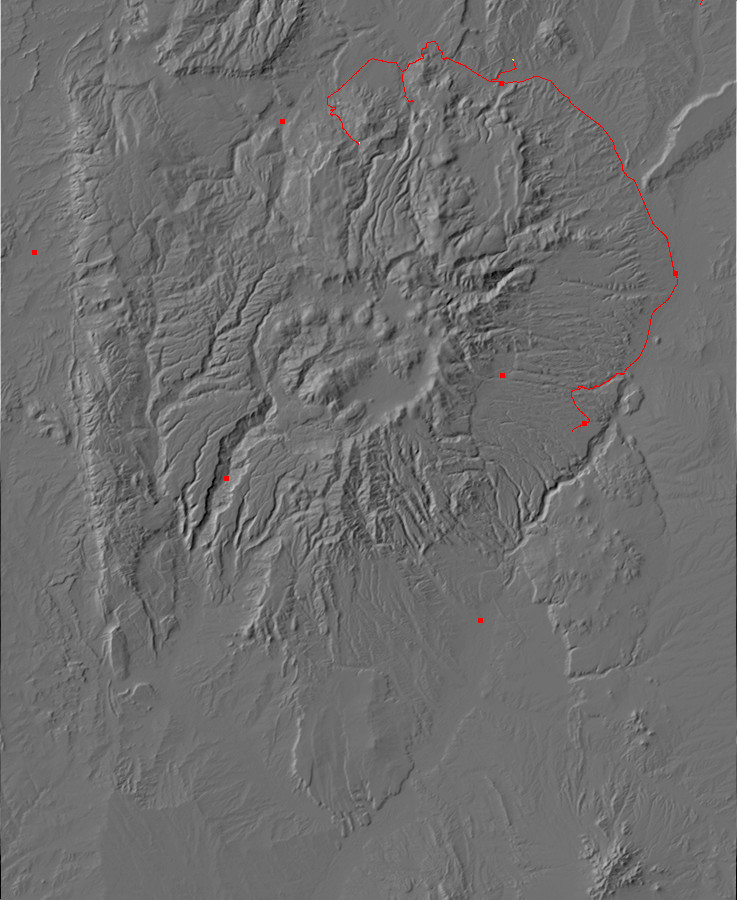

I retraced my route all the way to Abiquiu, then decided I had just enough daylight left to do a quick reconnaissance up the Polvadera Road (Forest Road 31). This is a (quite good) gravel road through Abiquiu Canyon and onto El Alto Mesa. This is a high plateau underlain by some of the older basalt flows of the Jemez volcanic field, and I have plans to do more exploration here.

The only catch is that the entire canyon and northern half of the mesa are part of the Abiquiu Pueblo grant, and, like all tribal lands, restrict visitors to the main right of ways. Still, I got a nice photograph of El Alto Mesa from the canyon.

El Alto Basalt. Looking south from 36 09.988N 106 21.330W

There is a nice picnic area here that was being used by the family driving the truck when I arrived. They appeared to be members of the pueblo; I would not make use of the picnic area uninvited.

From here the road wound up the cliff and onto the mesa. The road was thoroughly fenced off and signs indicated that visitors were not to leave the right of way until the road reached Forest Service land further south. Well, it’s their land; more power to them. I did not have enough daylight to get that far (I was not eager to hazard the return drive down the canyon in the dark) and the light was not good for photographs, but the area looks beautiful, and the portion on public lands is geologically interesting. I’ll doubtless be back.