About that shoulder

It looks like I won’t be doing nearly as much wanderlusting this summer as I could wish.

I met with my doctor to go over the MRI results Thursday. It seems I not only have a torn rotator cuff, but I tore it in the grand style. And then waited much too long to do anything about it: If I had taken it to the doctor in the first month or two, it would have been fairly routine to do the repair.

But I didn’t. And it turns out that the part of a ligament or tendon that attaches to the bone gets its blood supply from the bone. When it’s torn loose, that blood supply is gone, and the tissue begins to deteriorate. After this long (I injured myself ten months ago) the tissue often lacks the integrity to be stitched together or back to the bone successfully.

On the other hand, the doctor tells me that in the last couple of years his clinic has been having good success in patients like myself by using donor grafts to repair this kind of damage. So he seems fairly confident he can successfully reconstruct my rotator cuff.

But in the meanwhile, I’m looking at a few weeks of physical therapy, to loosen up my shoulder (it’s very stiff) and do whatever strengthening can be done to prepare me for surgery. Then he’ll operate. He’ll clean out all the deteriorated tissue, decide whether he can do the repair with my remaining good tissue, and reconstruct with donor tissue if he cannot. It turns out part of my biceps tendon is shot; this explains why there is a very tender spot on the front of the shoulder. So they’ll be cutting out the bad segment of my biceps tendon, too, and reconstructing that as well.

It hurts just to think about it. But the doctor seems confident he can restore pain-free use of my shoulder. Well, here’s hoping and praying.

After the surgery, it’s six to eight weeks of being in a shoulder brace with no shoulder motion at all. I wonder how well that will work; at present, the most painful time of the day is first thing in the morning, because when I wake up I quite automatically stretch, before I’m even really conscious. That has been good for sharp pain that pulls me fully awake and (on weekends) does not let me get back to sleep. I shudder at the though of that happening after the surgery; perhaps they have a way to keep my muscles relaxed. Botox?

The next six to eight weeks, I’m out of the brace but forbidden to lift anything heavier than five pounds. I’m allowed to type, so at that point I can go back to work. Fortunately, I have sufficient sick leave accumulated to cover the first six to eight weeks.

Then comes six to eight weeks of weight training to strengthen the repaired tissues. Ouch.

Only then — about six months out — can I think about hikes that might require scrambling. At least the doctor is optimistic I’ll be able to eventually. I’m probably not going to be permanently crippled.

Meanwhile, I’m doing what I’m still physically capable of, before the surgery puts me fully out of commission.

I’ve hiked the Potrillo Canyon area a couple more times, but taking different branches of the trail. Last Saturday I took the trail to the Water Canyon overlook.

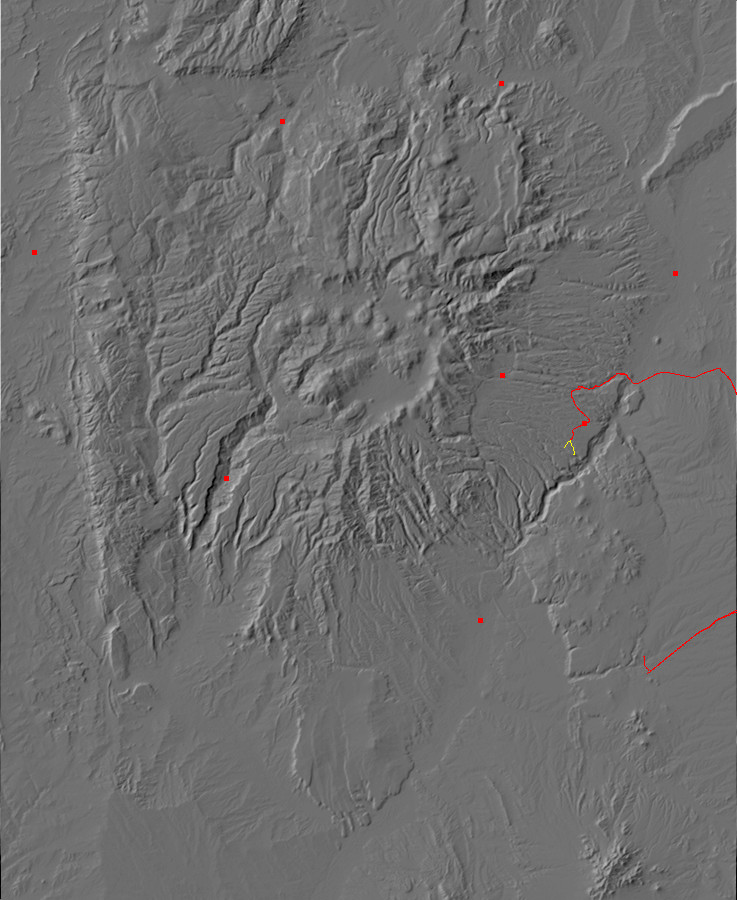

The trail heads south from the Potrillo Canyon trailhead (map) and to the foot of a mesa. Here (map) there is a cross trail (the whole area is crossed by trails).

One takes the cross trail to the left (east) a short distance, then takes another branch to the south and up the mesa.

I appreciate whoever lined the trail with the neat rows of rocks.

From here you have to be blind or stupid to get lost, because the trail follows the power lines almost to its end.

A short jog west to the next power line, and then a short distance to the canyon rim (map).

Water Canyon is below. At this point, it is not much deeper than Potrillo Cayon, but it deepens considerably to the east. Note the large dry stream bed running the length of the canyon. Also note the prominent cooling unit boundary in the far canyon wall, about halfway down. This marks the interval (hours to weeks) between pulses of the Valles eruption, 1.25 million years ago, that permitted the lower bed to cool slightly before the upper bed was erupted on top of it.

On the skyline in the first two frames is the Cerros del Rio, the basalt plateau erupted around 3 million years ago that forms the rim of White Rock Canyon. At left in the first frame is Ortiz Mountain (map), just peeking over the plateau of Ortiz Mountain Andesite to its north. This volcanic center was active about 2.32 million years ago, making it one of the younger eruptive centers of the Cerros del Rio. At the right edge of the first frame is the Twin Hills area, another andesite center active 2.53 million years ago. The fairly large mountain in the left side of the second frame is Montoso Peak, a basalt center 2.59 million years old. Just peaking over the right shoulder of Montoso Peak is Colorado Peak, an eruptive center that produced basalt and then andesite around 2.6 million years ago.

On the boundary of the fourth and fifth frames are the San Miguel Mountains, an early eruptive center of the Jemez dating back eight million years and more.

Some more odds and ends.

This road cut (map) is less than half a mile from my home, but I’ve only just gotten around to examining and photographing it.

This shows Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, sitting on top of Cerros del Rio basalt. This is appears to be a high point of the Cerros del Rio surface. On the other side of the road, the basalt is exposed in the canyon wall descending into Potrillo canyon.

Here’s a closer look.

On the right side of the cut, there is a thin layer of Tsankawi Pumice at the base of the Tsherige Member. This is air fall pumice that immediately preceded the pyroclastic flows that produced most of the Tsherige Member. This layer thins out and disappears to the left, where the Tsherige Member rests on sediments that in turn rest on Cerros del Rio basalt. These sediments appear on close examination to be a paleosoil — a fossil soil that had formed on the basalt before it was buried by the later eruptions. Where such sediments are found between the Otowi and Tsherige Members of the Bandelier Tuff, they are assigned to the Cerro Toledo Interval; but since there is no Otowi Tuff in this area, the age of these sediments is indeterminate and they cannot be so assigned.

Yesterday I took yet another hike into Potrillo Canyon, this time looking for a branch that would take me to Water Canyon further east. Along the way I stopped for a picture of colluvium (map).

“Colluvium”: That’s the hifalutin geological term for “dirt.” Well, sort of; it’s specifically dirt that is blown, washed, or simply falls down from nearby high terrain, in this case, a mesa of Bandelier Tuff. You can see that colluvium often includes quite sizable rocks and boulders, like the boulder to the right.

I successfully found the turn off to the Water Canyon Trail, aided by the large sign saying “Water Canyon Trail”, and climbed up the mesa on the south of Potrillo Canyon. Here (map) there is a fairly nice view into White Rock Canyon to the east.

On the skyline to the left are the andesite flows from the Ortiz eruptive center, and at center on the skyline are the Twin Hills, all part of the Cerros del Rio plateau.

The trail here is cut deeply into the tuff.

There are trails like this in a number of locations in the Los Alamos area, and at least some are ancient trails produced by the Ancestral Pueblo People. (We don’t call them the Anasazi anymore, because that turns out to be the Navajo name for them, which is more than a little derogatory. The two groups did not get along.) White Rock has been settled for about fifty years, and it’s not impossible that modern hikers have cut this trail in that time, but it seems a tad unlikely.

On the other side the trail descends into Water Canyon. Here I paused for a panorama.

The lighting was not great, so this one isn’t going to go into the book. You can see that the trail descends down the side of the mesa somewhat precariously. I explored just a little further down, finding a nice spot (map) for a view further down the canyon.

I wasn’t sure where the trail went from here, the sun was setting, and I have a bad shoulder, so it seemed prudent to retrace my steps. It was a nice two hour’s hiking exercise, though.

A few final odds and ends.

I drove to Santa Fe today to sing in an Easter concert. I planned to do some wanderlusting along the way, and I drove my wife’s old Santa Fe, which she was obviously reluctant to part with. Well, I can understand that; it’s surprisingly wrenching for me to leave Clownie the Wonder Car behind as I set out on an adventure. I felt like Luke Skywalker being asked if he wanted a fresh droid for his X-wing fighter to replace the old beat up one. Unfortunately, “not on your life” is not an option, even though we’ve been through a lot together. Clownie has had as much asked of it as I have any right to at this point.

Besides, the new car needed an oil change (about the only reason Cindy let herself be persuaded to part with it for the day) and it’s in better shape, with better ground clearance. Much more suitable for exploring the Cerros del Rio up close.

Except I didn’t get up close. I stopped once or twice for photos, such as this one of river terrace gravel on top of Chamita Formation near Otowi Bridge (map)

The river terrace gravel here was deposited by the Rio Grande tens to hundreds of thousands of years ago (the stuff is hard to date precisely) when the river level was much higher.

I got the car serviced, which took a while, and then I had just time to go get a panorama of the Cerros del Rio from the east that didn’t turn out well (not bothering to post) and then head to La Cienega for a couple of photographs of Espinaso Formation.

A very pretty breccia conglomerate (map), formed of bits of broken andesite from eruptions that took place in this area 20 million years ago — well before the Jemez. And, a little further down the road, an andesite dike of about the same age, right in the middle of the village of La Cienega (map).

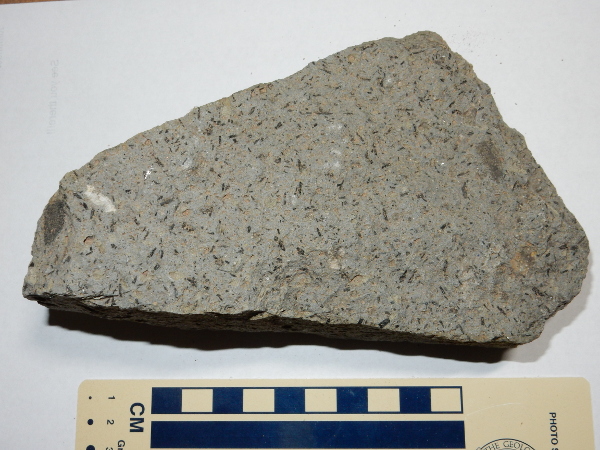

The andesite here is a very pretty hornblende trachyandesite. Trachyandesite: a rock formed from lava with an intermediate silica content, neither very high nor very low, with an unusually high content of sodium and potassium. Hornblende: an iron-containing silicate mineral that forms little black needles in the rock. Here, see for yourself.

You can click to enlarge (as with almost all the photos I post.) The long needly hornblende crystals are obvious. There’s also that dark clump of crystals to the right; this is either a clot (the crystals formed around some nucleus as the lava cooled underground before being erupted) or a mafic inclusion (this is silica-poor rock that got caught up in the liquid lava.) Both are fairly common in andesite.

Ran out of time. Didn’t actually get up into the Cerros del Rio; maybe next weekend, or the one after. Physical therapy starts Monday for the shoulder; I may be in no condition for driving trips by next weekend. We’ll see. Plus I have to be mindful of Cindy’s feelings; she naturally worries about me out in the back country with a bum shoulder. (And in her old car, no less.)