The Wanderpack and a rock glacier

It was my Friday off and the weather forecast was as promising as I’ve seen in a while. I decided this would be another good day to get a back country permit and do some exploring in the Valles caldera. Perhaps I’m just paranoid, but the Valles Preserve back country permit seems like such a good program that I fear it cannot last, and I want to take advantage of it as much as I can before it goes away.

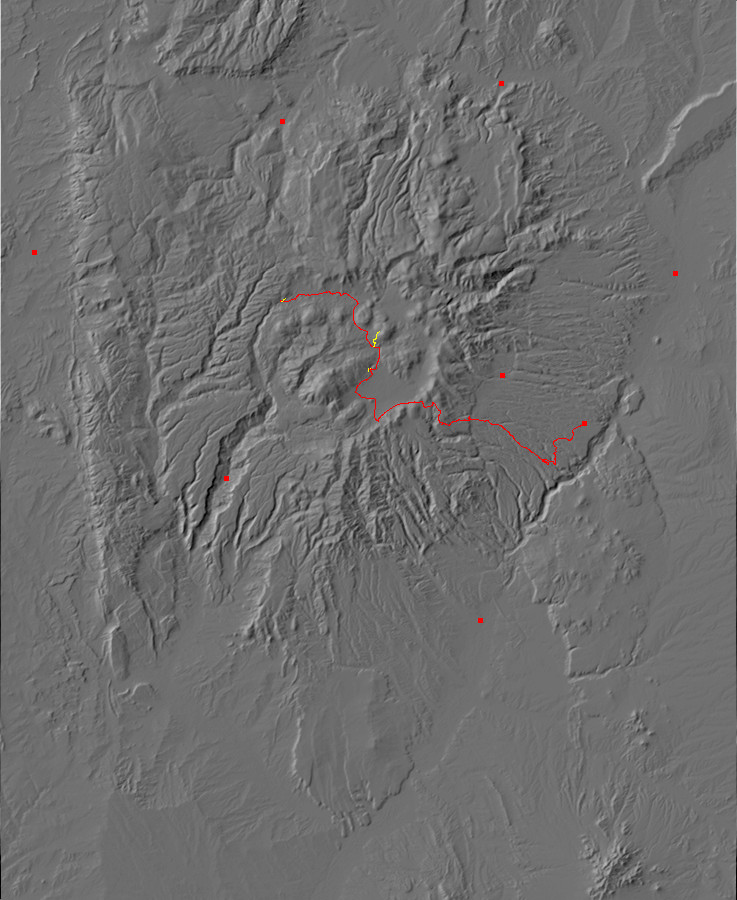

There are a number of geologic sites I want to visit in the caldera, but I decided that today I’d go with hiking to the rock glacier on the western flank of Cerros del Abrigo. I’d then try to visit the exposures of Abiquiu Formation in the extreme northwest part of the preserve. If time permitted, I’d take a look at the Santa Fe Formation beds around Cerro Trasquilar. And, on the way back out, I’d stop at Cerros Pinon to look at the beds of Deer Canyon Rhyolite overlying Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff.

I would be adding a new piece of equipment on this trip: the Wanderpack. Well, new to my wanderlusts, anyway. The backpack itself is almost as old as I am, a Boy Scout backpack left over from the Scouting days of my wife’s brothers. It’s held up remarkably well over the years, though, and many years ago I added a nice hip harness to help take the weight off my shoulders. Given the recent shoulder surgery, this seemed like a good idea, particularly since the pack I’ve been using is a cheap school kid’s pack that is already falling apart.

(And, I know what you’re thinking. “Wandermobile. Wanderpack. It’s like the old Batman series: ‘Holy all-nighter, Batman, I’m feeling awfullydrowsy.’ ‘Quick, Robin, to the Bat Expresso Machine!'” Look, some writers draw their inspiration from Shakespeare. I’m settling for bad 1960s television.)

So I woke at 6:00, got a big breakfast, packed all my stuff (taking particular care to make sure my Valles geologic map actually made it into my pack this time), packed a trail lunch, looked in vain for an umbrella (I would regret its absence later), let the dog out, left a flight plan for Cindy (who made a particular point of asking me for one this morning), and headed out. I paused along the way for one photograph, of some particularly prominent cliffs of Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff that I can see from my bus stop in White Rock every morning and which stand out particularly well as you drive along State Road Four, from about here:

Rabbit Hill is located on the skyline directly behind the Tsherige Member cliffs. It’s a dome of Bearhead Rhyolite that has a radiometric age of 6.65 million years. The prominent cliffs, located here, stand out so much because they are on the upthrown side of the Pajarito Fault. The rocks immediately around and below them are all Otowi Member, the older member of the Bandelier Tuff.

I proceeded on into the caldera, to be greeted by the kind of sight that makes you laugh out loud for delight.

I’ve seen the Valle Grande socked in with clouds like this before, but not in many, many years.

This illustrates one reason the valleys of the Jemez are not forested: They are perfect traps for frigid air, which is more than tree saplings can take. Another reason is that the valleys are floored with thick, fine clay beds that give tree roots little purchase.

The road into the preserve headquarters was somewhat the worse for wear, with a number of muddy potholes. Lots of recent rain. I secured my back country permit — the rangers there are beginning to recognize me by sight — and proceeded on up to my trail head at the foot of Cerros del Abrigo. The dome whose flank I would be climbing loomed above.

Proceeding up the trail, I turned north and found that this was a serious trail, with amenities.

I was grateful to be rid of some extra liquid I didn’t really need to keep.

The hill to the left is colluvium, but the hill to the right is a ridge of Valles Rhyolite; Cerros del Abrigo Member, unsurprisingly. To be precise, it’s part of the earliest of four flows making up the cluster of hills. This flow has not been dated, but the youngest flow of the Cerros del Abrigo has a radiometric age of 973,000 years and the others are probably not much older. All came from a vent along the ring fracture where the Valles caldera collapsed in the great eruption of 1.21 million years ago.

I took a close look at an outcrop.

Yup, looks pretty much like every other outcrop of Valles Rhyolite I’ve seen. Phenocrysts of feldspar and quartz in a light ground mass.

I headed on up the mountain, appreciating the occasional reassurances that I was on the right path. Particularly welcome in this case, as the road becomes indistinct right where it turns west.

“None shall pass!”

This trail was particularly bad for fallen trees, due to forest fire damage long enough ago that the roots are starting to rot out. I did a lot of dodging and weaving, and stopped counting fallen trees across the trail at around 15 or so. Unsurprisingly, there was also some serious gullying in the areas that had the fallen trees. Pity.

But life goes on. Including wildlife.

I had noticed a freshly beaten path in the grass, took it for a tire track, and wondered why the rangers would make the effort across this bad a road. Then I saw the densely packed elk tracks and realized a sizable herd had come through here single file recently. I later caught a glimpse of one or two ahead on the trail, but could not get my camera into action in time for a picture.

Some flow-banded rhyolite in the trail bed.

Rock in a road bed is always suspect, since fill is often brought in from elsewhere. But this is probably local.

The road turned east around the shoulder of an old rhyolite flow, and the dome was visible ahead.

Then it got interesting. I had made a mental note from Google Maps that there was a fork at one point where I needed to be sure to go right. Well, here we are:

Incidentally, the arrow labels read “stay on the trail”, which is not actually the rule in the Preserve. Either this dates back to an earlier set of rules, or the sign-posters used whatever arrow stickers happened to be available. Anyway, it looked like I should go right here.

Except no. The trail almost immediately turned to the southeast rather than continuing more or less ahead. And then I hit the fresh debris flow.

From recent fire damage further up the dome. I decided this was not the way I wanted to go, retraced my steps, and took the left branch.

And was soon relieved to find the fork I was expecting.

I headed right and soon reached the toe of the rock glacier.

A rock glacier is a kind of flow composed of boulders set in an icy matrix. It flows something like an ice glacier, but only boulders are visible on the outer surface, which insulate the ice in the interior. There are no active rock glaciers in the Jemez — this one certainly lacks any icy matrix — but there are several suspected old rock glaciers, left over from the last glaciation. (True glaciation did not get this far south.) This is one of the best candidates, since it appears to have definite pressure ridges and other features typical of rock glaciers.

For example, the very steep toe.

The flanks likewise are remarkably steep.

I was struck by the level, gentle slope of the hillside on which this glacier sits. There are simply no scattered boulders beyond a few feet of the edge of the flow.

I climbed up onto the flow.

The pictures don’t quite convey the bowl shape of the glacier surface. One gets the impression that the center was significantly deflated when the ice melted away, which is probably about right.

The rocks are covered with lichen. This suggests the flow has not been active in a very long time. There is actually such a thing as lichenometric dating, though it’s very uncertain. But one can make a guess that the flow has not moved in at least two thousand years.

I did notice one patch at the south edge that looked very fresh. This small area had either moved recently, or a forest fire burned off the lichen. Some of the boulders were spalled, as if they had been subjected to fire. I took a photograph, but something went wrong and that photo file was crapped when I got home. At least the rest of my photographs turned out.

You can see a road crossing the flow in the upper photograph. Here’s a panorama looking west from the edge of that road.

Behind the trees in the first frame is Rendondo Peak and Redondito. The second frame shows the rugged terrain of debris flows, megabreccia, and low-volume Deer Canyon Rhyolite flows northeast of Redondo Peak.

San Antonio Mountain is on the skyline towards the right of the second frame. It’s the youngest and most distant of the ring domes, of which Cerros del Abrigo is one. Other ring domes are strung out between San Antonio Mountain and where we are standing: Cerro Seco, Cerro San Luis, and, just peeking over the trees at the center of the last frame, Cerro Santa Rosa. Unless it’s Cerro del Trasquilar. The Forest Service map has it as Cerro del Trasquilar, with Cerro Santa Rosa being a smaller dome to its north (not visible here); geologic maps have these reversed. Bother.

The ring domes all erupted through the ring fracture left by the Valles eruption 1.21 million years ago. All are underlain by rhyolite of similar composition, the Valles Rhyolite. We saw a sample earlier on this trip.

Well, cool. Now all I had to do was get back down; it’s always harder going down. (Counterintuitive to tyros, but experienced hikers know this.) I opted for going down on the forested flat ground just to the side of the rock glacier. From here I got a nice view of Cerro Santa Rosa/del Trasquilar.

With Cerro San Luis peeking over the shoulder at the left.

The hike back was relatively uneventful, though I did poke a couple of small holes in my hands negotiating all the fallen logs. One of which had knocked over a signpost.

The fire damage is depressingly bad in spots.

I got back to my car and found it was only 11:00. However, clouds were beginning to build up. I decided I had better get on to the northwest moat area quickly.

But I did stop to photograph a nice tuff bed along the road.

A very pretty lithic tuff, exposed in a borrow pit. The geologic map identifies this as an ignimbrite of the Cerro del Medio dome, which is on the other side of Cerros del Abrigo.

A nice view of Cerro Santa Rosa/Cerro del Trasquilar dome as I drove by.

From there to the north moat of the caldera, Valle San Antonio, which is the low ground between the ring domes and the north caldera rim. Paliza Canyon Formation two-pyroxene andesite around 9 million years in age is exposed at the base of the caldera rim.

I took a close up picture, but the photograph came out a bit blurry and was unrevealing in any case; this outcrop is thick with lichens and somewhat weathered, and (being on the Preserve) I did not feel free to create a fresh surface by breaking part of the outcrop.

Two-pyroxene andesite: This is a rock with an intermediate silica content, compared with the high-silica Valles Rhyolite we’ve seen so far. It is distinctive for having both calcium-rich (clino-) and calcium-poor (ortho-) pyroxene in its makeup. This is supposed to to say something distinctive about the environment in which the magma formed, but there’s apparently some uncertainty what.

I continued on west, watching with some concern the clouds building up. To the south, a nice view of Cerro San Luis.

This ring facture dome has a radiometric age of 800,000 years.

Ahead, the caldera north rim.

It’s hard to be sure from my geologic map, but I believe the lower cliffs exposed in the rim are Paliza Canyon Formation andesites while the top of the rim is La Grulla formation andesite.

It was clouding up fast. Up until now, the road had been in okay shape, with just the occasional muddy pothole. Once I got past Warm Springs, though, the road deteriorated rapidly. And then the hail hit.

The photograph isn’t great — it was taken through a wet windshield, after all — but the road is covered in small hail.

It passed. I carefully made my way down the increasingly bad road, and was rewarded with a wonderful view of megabreccia to the west.

The hill in the foreground (steeper to the left) and the two rugged outcrops behind them are giant slabs of Paliza Canyon Formation andesite that originally sat on the caldera rim behind them, but which broke off and slid onto the caldera floor immediately after caldera collapse. Spectacular as these are, they are not the most spectacular megabreccias in the Valles caldera; there are megabreccia blocks near the caldera center north of Redondo Peak that are half a mile long.

San Antonio Mountain, with a radiometric age of 557,000 years:

I continued along the road, including past a couple of very badly washed out sections, only to find myself in another “None shall pass!” situation.

They seem rather serious about not wanting you to go further, don’t they? The actual Preserve boundary is about another hundred feet along the road.

I turned around — fortunately, there was plenty of room here — and worked back. I was trying to spot the Abiquiu Formation beds from the road, but, alas, no luck. I turned around yet again and came back to the small parking area near here and started hiking up San Antonio Creek.

Clouds were gathering; I had not been able to find an umbrella, so I would have to hike fast and trust my luck.

The hill to the left looked promising.

The white color suggested Abiquiu Formation, and some of the rock looked very much like sandstone.

Other rock looked rather like Pedernal Chert of the Abiquiu Formation.

But when I checked my GPS coordinates against my geologic map after I got home, I found that this is mapped as very early lake sediments, which can be highly silicified from the hot, acidic water of the early caldera lake. Okay, not Abiquiu Formation, but still pretty cool.

Further on down was what I took for Valles Rhyolite.

After I got home and checked my GPS position, I found that this was unusually densely welded Otowi Formation. Well, unusually densely welded for the Los Alamos area; it tends to be more densely welded northwest of the caldera.

Could that be Abiquiu Formation exposed in the draw ahead?

No, it could not. On close examination:

I poked it with a finger; it looked and felt like unwelded Otowi Formation. And that’s what I confirmed later with GPS and map.

South of San Antonio Creek were some promising-looking beds.

These turn out to be more early lake sediments, though impressively silicified at this location.

Finally, down the valley:

But at that point the rain started coming down again, and after a moment of hesitation, I decided that I best get back to my car. Which is a shame, because if I’m reading my map and position right, the light outcropping is, in fact, Abiquiu Formation.

At least I got a photo from a distance.

So why do I care? I devote a long section of the book to this formation, because it’s a very early Rio Grande Rift fill sediment whose outcroppings nicely trace the west boundary of the Rift in this area.

I considered the time, and decided there was not enough to properly visit both the east end of the moat and Cerro Pinon. So I headed out to Cerro Pinon.

Cerro Pinon is part of the Redondo resurgent dome, but Jaramillo Creek has eroded a valley that cuts it off from the rest of the dome and exposes the beds. The resurgent dome is where fresh magma entered the magma chamber almost immediately after the Valles eruption and pushed the caldera floor back up to produce Redondo Peak.

I hiked up to the dome from the parking area and observed the same white plug that Bruce Rabe and I first noticed last spring.

The brown rock exposed along most of the road cut is Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, laid down on the caldera floor 1.21 million years ago when the caldera formed. But the white patch is a very different rock.

It is a much whiter tuff than the surrounding Tsherige Member and contains some lithic fragments that look like andesite. It’s not hydrothermally altered Tsherige Member. My geologic map shows a vent at this precise location, so I figure the geologists who made the map also spotted this outcrop and interpreted it as an eruptive vent of the Deer Canyon Rhyolite that has been exposed by erosion.

I started up the hill. There was a nice outcropping of Tsherige Member, though heavily encrusted with lichens. Being on the Preserve, I refrained from creating a fresh surface by hammering.

Further up is what appears to be the upper contact of the Tsherige Member. I counted no less than sixteen geologic sample boreholes on this exposure; evidently this was of considerable interest to some geologist at some point. It has more holes in it than the typical major party political platform. My geologic map shows an age of 1.26 million years, within the margin of error of the Valles eruption.

Above this bed is Deer Canyon tuff, though it’s heavily mantled with soil and I had to work down the contact to find a good exposure. Evidently, I was not the first.

Definitely the same kind of tuff as in the vent below.

Deer Canyon Rhyolite is a low-volume post-caldera formation. It was erupted as tuffs and massive flows across the floor of the caldera very shortly after it had collapsed.

According to my map, above this tuff, there are massive flows of Deer Canyon Rhyolite. However, above that is debris flow deposits. So any rock that I was not certain was a bedrock exposure was going to be suspect. Sure enough, I had a tough time telling what was Deer Canyon Rhyolite and what was erratics brought in with the debris flow. A further complication is that rhyolite can be quite varied in appearance, even within a single flow.

But this is almost certainly Deer Canyon Rhyolite, with a large xenolith.

The xenolith could be Paliza Canyon Formation from deep below the caldera floor, or it might be “cooked” Bandelier Tuff.

This is probably not Deer Canyon Rhyolite.

It looks like Tshicoma dacite. Still, rhyolites can sometimes have large phenocrysts.

This looks like flow-banded rhyolite.

This is definitely Deer Canyon rhyolite.

I climbed down the hill, very slightly bothered that I was not quite sure of the identity of some of the rocks I had photographed. I had hoped for better exposures.

Hiking back, I reached a side road that headed up onto a hill mapped as debris flows plus Deer Canyon Rhyolite. Well, heck …

Again, I had the problem of telling erratics from the nearby debris flow deposits from actual outcrops of Deer Canyon Formation.

Plus fire hazards. Yeah, yeah, yeah …

Nature wants to kill you.

This is a pretty certain outcrop of Deer Canyon Rhyolite.

This looks like flow-banded rhyolite, but it also has the look of an erratic brought in by a debris flow. Suspect.

Here‘s some more of the Tshicoma Dacite-ey stuff that is probably an erratic.

This looks more promising, though it’s clearly not bedrock.

In fact, since there are no exposures of Deer Canyon Rhyolite on public lands outside the Preserve, this is going to have to do as my type specimen for the book. I’m quite certain this is in fact Deer Canyon Rhyolite, because a short distance away:

This is clearly bedrock, it’s clearly rhyolite, and it’s in an area mapped as Deer Canyon Rhyolite. This has simply got to be the real McCoy.

So this became my personal type section of Deer Canyon Rhyolite. It allows me to confidently say that all the photographs from earlier on this wanderlust that are the same kind of rock are Deer Canyon Rhyolite. The only uncertainty is whether some of the other rocks are different facies of Deer Canyon Rhyolite.

Swell. It was now nearly 4:00 and I had promised Cindy I’d be back by 5:00. I hiked back to my car, signed out at the preserve headquarters, and drove home.

I did make a very fast reconnaissance of the American Springs area, which has been recommended to me by a commenter at this blog. The road in looks pretty good and the area does look interesting. I will make a proper exploration sometime.

And when I got home, though my legs were a bit rubbery and one foot was sore from climbing over that rock glacier, I did not have that absolutely beat up feeling I’ve had after some other recent trips. Partly that may be my shoulder betting better, but mostly I think it’s that the new Wanderpack is so much of a pleasure compared with the old one. Putting the weight on the hips is so much less hard on my upper body, it’s not even funny. Worth the effort to get set up with a new backpack.