Wanderlusting El Alto

So Labor Day was to be my big day of wanderlusting. I had played Mr. Fixit Friday, had taken Nathan to his tournament in Albuquerque Saturday, and I felt entitled to a day just for looking at rocks.

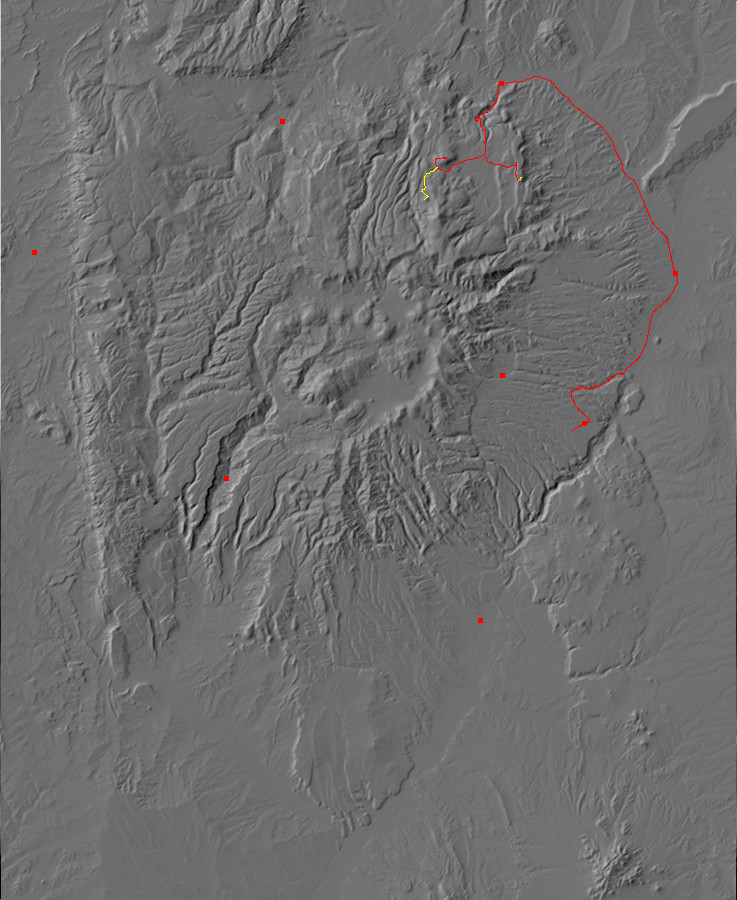

My destination would be El Alto, the easternmost of the two great alpine plateaus of the nothern Jemez (the other being the La Grulla Plateau.) Both are underlain by basalt, with domes and flows of more silicic lava, but La Grulla is slightly younger at 7 to 8 million years versus 8 to 10 million years for El Alto.

Because the weather report indicated a moderate chance of rain later in the day, and because El Alto is about the worst spot in the Jemez for lightning during monsoon season, it was prudent to head out as early as possible. So I got up at 5:00, same as I would on a work day; ate a good breakfast; packed my pack; let the dog out; and loaded up and headed out before sunrise. My route took me through Espanola to Abiquiu, where I took Forest Road 189 south into Abiquiu Canyon. Most of my route from here onto El Alto would be on private or tribal lands, with posted instructions to remain on the road.

The road turns sharply to climb the mesa just as it reaches an impressive face of El Alto basalt. I’ve photographed this before.

El Alto Basalt. Looking south from 36 09.988N 106 21.330W

Once atop the mesa, Polvadera Peak and Cerro Pelon came into view. Polvadera Peak is the third highest point in the Jemez at 10,419 feet. Both Polvadera Peak and Cerro Pelon are underlain by dacites of the Tschicoma Formation. These are volcanic rocks with a moderately high content of silica, forming a highly viscous magma.

The bench north (right) of Cerro Pelon is underlain by El Alto Basalt, which, like the Tschicoma Formation, is in the ballpark of 3 million years old. The impression I get from the geologic map is that this basalt erupted high on the north flank of the existing dacite dome following collapse of the flank. The basalt lava covered the landslide and produced what looks at first glance like a surprisingly high-aspect flow for such a low-viscosity magma.

A little further down the road, the view became good enough for a panorama.

I like this one because Cerro Pedernal is just peeking over the skyline in the third frame.

Sure enough, there was an even better spot for a panorama on a little further.

The ridge at extreme left is unnamed on my map, but is the steep face of a fault block underlain by olivine basalt of the Lobato Mesa Formation with a radiometric age of around 9 million years. Most of the other mountains and hills on the skyline are underlain by Tschicoma Formation, about 3 to 5 million years old, while the mesa itself is underlain by Lobato Mesa Formation basalts 9 to 10 million years old and El Alto basalt 3 million years old, with a thin veneer of eolium (windblown sediments) and alluvium (waterborne sediments). Tschicoma Peak, the highest point in the Jemez at 11,561 feet, peeks over the shoulder of Polvadera Peak at the left edge of the second frame.

Further south I crossed a ridge of El Alto basalt and the road got slightly worse. My turn was to the east towards Lobato Mesa, my first stop of the day. The road was muddy in patches, but not too bad until I reached an arroyo across the road, which took careful negotiation. Once again, I was grateful for the Wandermobile. The road continued through a narrow valley between olivine basalt flows and to a small artificial pond swarming with cattle.

A mixed herd of steers, cows, and calves. One of the momma cows took up a “Step out of your car, and I will unseam you from the knave to the chaps and set your head upon my battlements” stance.

I did not get out of my car.

The road here was a bit uncertain. I thought I was supposed to go north, then up the face of the escarpment to the east, but it looked like the road south might go up the escarpment. Wrong. I backtracked, went north, and found an iron gate (fortunately, open) and the road continuing on up the hill.

This was just a bit scary. The road was reasonably good, but the escarpment was very steep below it, and it looked like there were not going to be any turnaround points for a long, long distance. I gulped, screwed my courage to the sticking place, and went on up.

Meh. Once I was to the top, it didn’t seem so bad. And there was my road to the eastern edge of the mesa, though the road got indistinct enough I decided to walk the rest of the way.

It was a nice little walk, and there were some good exposures of olivine basalt of the Lobato Mesa Formation on the way.

A nice gray basalt, with dark brown flecks of iddingsite formed from alteration of olivine phenocrysts. This makes this a fairly low-silica rock.

Technology is everywhere.

But there was something oddly familiar about this place. I finally dredged up a memory: Woodcutting with my father and older brother, when I was probably in my very early teens. This is Forest Service land, and if it is the place I remember, they must have thinned the area and then opened it to wood collection.

I sometimes think my father got a bit of the wanderlust at times.

Some of the basalt near the eastern escarpment is scoracious.

Alas, it doesn’t show up well in the photograph, so this is not one for the book.

And then the escarpment itself.

Lots of stuff in that picture. In the first frame, we see the escarpment to the north, with the Tusas Mountains in the background. The escarpment itself is not a fault escarpment, or at least no evidence of a controlling fault has been found; the faults here tend to be down to the west anyway. This is an erosional scarp, formed because hard Lobato Mesa basalts rest on very soft sediments of the Ojo Caliente Member, Tesuque Formation, Santa Fe Group.

In the second and third frames, one sees Chama-El Rio Member, Tesuque Formation, in the valley floor, with a prominent ash bed. Beyond are hills of Ojo Caliente Member, with a fault on their western side. This fault is downthrown to the west. In the distance in the second frame is Sierra Negra.

On the boundary of the third and fourth frames, beyond the hills of Ojo Caliente Member, are ridges cored with basalt dikes. These appear to be the same age and composition as the Lobato Mesa Formation, and point to an eruptive center to the east that is now completely eroded away.

The plateau in the fourth through sixth frame looks like a basalt plateau thrown down by a fault, but the geologic map has it underlain by Santa Fe sediments and shows no fault. It looks like an erosional surface, left over from a time when the Rio Grande had not cut down nearly as deeply as it now does. It must be quite an ancient surface given its height above the current river level; I won’t even venture a guess.

The final frame shows La Sotella, a remnant of an ancient shield volcano of the Lobato Mesa Formation. The lower plateau at the right side of the next to last frame is a separate flow, thrown down by a fault.

I know. The lighting is all wrong; this should have been taken in mid-afternoon. But, given the weather report, it seemed possible that by mid-afternoon this area would be under a thunderstorm. You have to play the odds. I lost; this area remained under clear skies almost the whole day.

Which is too bad, because La Sotella is made up of numerous thin flows, which barely show up in this lighting.

I had my big binoculars with me, and spent some time perusing the scene. I could make out some of the flows on the flank of La Sotella, and the dikes down in the valley were unmistakable. I could also make out the diatomite mine east of Cerro Roman. Alas, I have no way to take photographs through the binoculars.

I did get a decent photograph of ash beds in the Chama-El Rito Member in the valley.

The beds are visible at the southern edges of the small hills right and left of center. These are marked on the geologic map for the area, but not further identified or described.

Back down the west side of the mesa. Of course, I paused for another panorama.

You can perhaps see why the road made me a bit nervous.

In the middle distance, running almost the length of hte panorama, is a series of forested hills. This is the western edge of a fault block, similar to the one from which photograph was taken, that is tilted to the east.

I paused again along the road at an outcrop of breccia.

On examination, this proved to be a local colluvium with some calichification. The outcrop easily crumbled to the touch. Nothing spectacular.

I threaded the Wondermobile the rest of the way down the mesa, past the pond (which had more cows than ever, and no friendlier) and back to the main road. Then to the road to Cerro Pelon. Which was very cheerful this morning:

The road got a little crummy south of Cerro Pelon. I drove on, but with some trepidations. No road for a large vehicle …

I am such a wimp.

Ahead, a flow of Tsherige Member, Banderlier Tuff.

The Tshicoma highlands shielded most of El Alto from the pyroclastic flows that produced the two main members of the Bandelier Tuff, 1.65 and 1.21 million years ago. This flow lapped over the edge of the plateau, which is just to the west of this point.

The road climbed onto this flow, and there was my trailhead.

Except that the road to the left, which was my trail, looked better for once on the ground than in the satellite photo. What the heck. I started the Wondermobile on down it.

Well, all right then. At least I shortened my hike a bit.

I climbed over the gate (National Forest both sides; no reason not to) and found the road beyond in dismal shape. It looked like a rabid bulldozer had got loose there. But just then an ATV came puttering up the road from the other direction, and turned onto a side road I had not seen. Presumably the road continues to the area where I saw the trailers earlier.

No matter. I continued on down the trail, passing a high dome of Tschicoma dacite and some more Tsherige Member.

The trail climbed on to the flat surface of this flow, where I would spend most of the rest of the hike. It was a pleasant day and the trail was forested enough to be shady.

A ‘shroom:

And a piece of obsidian. There is a fair amount of obsidian on El Alto, but something of a mystery why. One theory is that it was scattered by early man, but there is so much that this stretches credibility. On the other hand, the only obvious natural source is the El Rechuelos domes we will be seeing shortly, and it’s hard to see how erosion could scatter the obsidian so far from the natural drainages from these domes. In this case, we are so close to the domes that this is the likely explanation.

Notice that this is relatively light-colored and translucent obsidian. Most of the bits of obsidian I saw in the area were like this, and I assume this is characteristic of El Rechuelos obsidian.

Though a clearing, I saw what I took to be the northern El Rechuelos dome at first.

Turns out this was just a foothill of Polvadera Peak, underlain by Tschicoma dacite.

As I reached the end of the Tsherige Member flow I had been hiking on, the actual dome came into view, with Polvadera Peak in the background.

This was my destination for this hike.

Geologists gave the name El Rechuelos Rhyolite to a group of at least eight low-volume rhyolitic exposures in the northern Jemez. With further study and petrological analysis, these have been broken down into: two older domes, 5 to 7 million years old, that appear to be northern outliers of the Bearhead Rhyolite of the southern Jemez; a dacitic tuff ring that appears to be part of the Tschicoma Formation; the two domes in the area I am hiking to, which appear to be a truly distinct formation, around 3 million years old, produced by extreme differentiation of Lobato Mesa magma; two small exposures in the canyon below these domes that appear to be large landslide blocks off the domes; and a poor exposure (though rich in obsidian) on the southwest flank of Polvadera Peak that has not been much studied.

As I descended the Tsherige Member flow into the canyon below, I caught a glimpse of white through the trees. This was in about the right location for one of the landslide blocks, but I decided not to divert that way.

The road continued up the canyon, taking me around the north flank of the dome. I did not expect this; I had not studied my map close enough, and this was not the old forest road I thought I was on. Still, this one took me more or less straight to where I wanted to go. No harm, no foul.

I came to a meadow, separated from the dome by a small arroyo.

Well, this was as good a place as any, so I crossed the arroyo and started up the dome. The lower slopes were littered with promising-looking white bits of rock: rhyolite.

Further up, the clasts became larger and more numerous, and the view of Polvadera became better.

Approaching the top — so I thought:

By now I was huffing pretty good. I’ve had a formal stress test at the cardiologist’s; I figure these are my updates.

The top. Alas, too many trees in the way for a decent panorama.

But plenty of rocks. This one displays a barklike texture that probably represents a cooling surface.

I’ve seen a similar texture on rhyolite at Rabbit Mountain on the south caldera rim. This is probably as good a place as any to show my sample.

The map describes this as a pumiceous rhyolite, and it does have a little different texture than the other rhyolite samples I’ve seen. Under a powerful loupe, it looks almost crystalline, or perhaps like a mass of tiny glass beads compressed together. I suspect the latter is actually quite close to the truth.

I could see through the trees that I was actually on a subsidiary summit, and the true summit to the south looked like it was almost bare of trees. Gosh darn, I was out of breath, but you know? I don’t know that I’ll ever be this way again. I climbed to the true summit.

More ‘shrooms:

I dunno; I guess I’m just a fun guy.

(Pause to let you recover from that.)

It would be incorrect to say that this is what I live for. I have a wife, children, and a church. But it might be correct to say that this kind of thing would be sufficient reason to live.

At left, the near orange mesas are of course the familiar Bandelier Tuff. Beyond, on the skyline, is La Grulla Plateau. The cluster of hills are, I believe, dacite domes of the Four Hills complex, sitting on the basalt and andesite making up the plateau. El Alto and La Grulla Plateau channeled the pyroclastic flows of the Valles event, 1.2 million years ago, into the low ground between to form the Bandelier Tuff mesas.

Cerro Pedernal, beloved of artist Georgia O’Keeffe, appears on the left side of the third frame.

The far skyline in the third and fourth frames are Mesozoic beds of the Colorado Plateau.

Zooming in on Cerro Pedernal.

Canon de Cobre to the north, with the Tusas Mountains in the distance.

This canyon would be way cool to explore some time. Its north rim is on Forest Service land, and it appears to be accessible by dirt road.

Time to descent the dome. Shelf fungus:

Going back up the trail, I managed to lose my footing on some loose dirt and went down hard, pack and all. Fortunately, I went down on the shoulder that didn’t just get operated on. Bruised that hip and skinned the shin something awful. I thought about posting a photograph, but, really, who wants to see that?

All my extended family, judging from how I was expected to show off my scars on my shoulder during our family reunion this summer. Still.

A nice view of a dacite dome near the end of the trail.

My final adventure would be drive to the top of Cerro Pelon, and perhaps grab a sample of El Alto basalt on Forest Service land where this is legal. The road up the west side of the cone gave some nice views.

Yeah, my middle ear is usually better than that. Must come from taking the picture while seated in a car on a steep road. This should be a bit less disquieting:

I had notice some smoke below Cerro Pedernal clear back on the north El Rechuelos dome. It looked like it was starting to really get going.

I haven’t heard anything about it since. Either a controlled burn, or rapidly contained. This time of year, the monsoon helps.

A panorama from the north flank of Cerro Pelon.

At left, the fire and the La Grulla Plateau. Across the first two frames, Bandelier Tuff, with Cerro Pedernal on the skyline. Mesozoic beds of the Colorado Plateau across the rest of the skyline, with Abiquiu Reservoir visible.

The ridge to left is dacite forming the west flank of Cerro Pelon. The ridge to right is underlain by El Alto Basalt erupted from Cerro Pelon.

I found a convenient turnaround near the radio towers, and here was some El Alto basalt.

This was the closest to a solid outcrop I saw anywhere; the entire north slope of Cerro Pelon was covered with what looked like colluvium. My sample:

I was taken aback. This has numerous coarse phenocrysts, something I’d expect more in a dacite. I wondered if that was, in fact, what this was. However, the Tschicoma dacite hereabouts is much lighter in color. I figure this must be the real thing.

This shows the difference.

The reddish boulders are Tschicoma dacite. The gray boulders are El Alto basalt.

Down the mountain and out the road. One final shot:

Geologists have interpreted the dome on the right as a single flow coming out of the summit crater.

Most of El Alto is underlain by beds of eolium and alluvium (wind- and water-transported sediments) presumably resting on Lobato Mesa and El Alto basalt flows. However, there are a few ridges of coarse gravel interpreted as Puye Formation.

The Puye Formation is prominent on the east side of the Jemez, where it forms gray cliffs in lower Pueblo Canyon on the main highway to Los Alamos. It is a mixture of lahars, debris flows, and river deposits of ash and rock from the Tschicoma Formation. The beds east of the Jemez were preserved because they formed in a kind of basin, the Diamond Drive Graben, where they were overlain by Bandelier Tuff. El Alto is not a basin and no Bandelier Tuff flows were deposited here, so the sediments off the Tshicoma Highlands to the south were only spottily preserved.

Once again, the golden highway:

On the way out, I noticed some impressive caliche along the road. At least, that’s what I now think it is.

I snapped a photo because I wasn’t sure what I was looking at, and marked the coordinates. The geologic map has this area simply as El Alto basalt. I didn’t take a sample, because private land.

Which got me thinking about sedimentary beds, I guess, because I snapped three more pictures on the way home, all of sediments.

First, at the bottom of the descent down El Alto into Abiquiu Canyon. I just thought this was a nice exposure of Ojo Caliente Member, Tesuque Formation, Santa Fe Group — an eolian Rio Grande Rift fill sediment.

Further down the canyon, there was another exposure of the Ojo Caliente Member, will really impressive cross bedding.

This just screams eolian.

Judging from the satellite photo, this may be a borrow pit.

Finally, an impressive gravel bed just east of Abiquiu.

This is apparently an old axial gravel of the Rio Chama, deposited on Chama-El Rito Member, Tesuque Formation. The flat ground above has ruins of an Ancestral Pueblo People city, Poshuinge, which it turns out Bruce Rabe and I looked over on an earlier trip. Alas, I didn’t think to take pictures then.

I hate to get the private residence in the photo, but it was about the only safe place to pull over with a clear view of the bed.

And home.