Columbus Day wanderlust

Next Friday I have a dental appointment, and Saturday Cindy has a wedding in the family. The week after, I will be in Colorado for the occultation. That means I will be catching up on chores the weekend after. I will have a long weekend just before Halloween, but the weather is always an unknown, and on November 4 the back country season ends in the Valles preserve. So, with the forecast calling for beautiful weather on Columbus Day, which is a holiday where I work, I could not resist making what may be my last trip into the caldera this year.

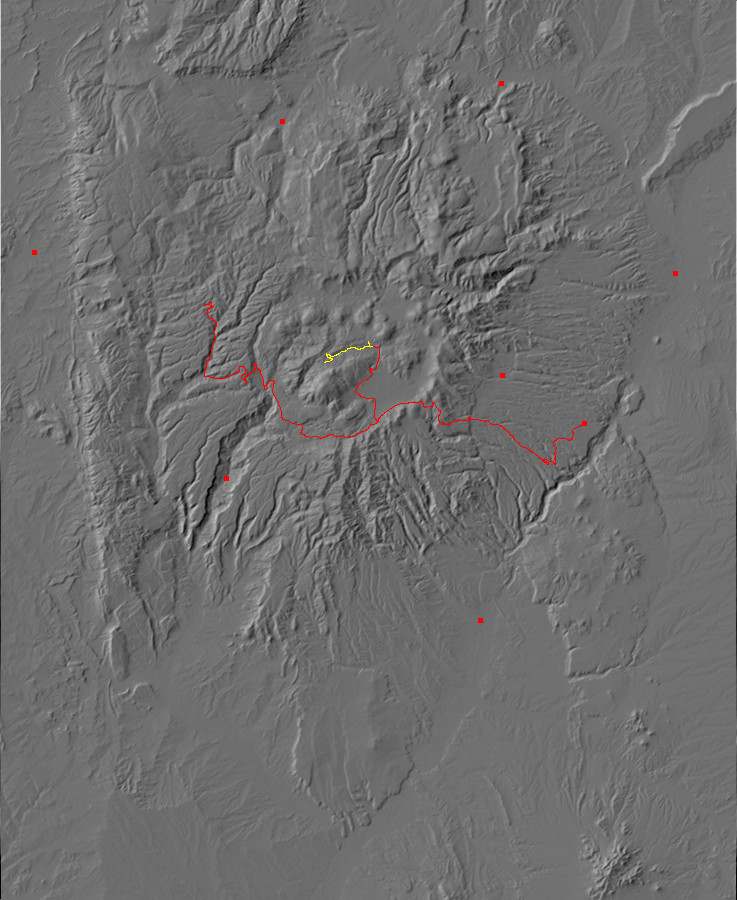

My objective was to hike up Valle Jaramillo from the trail head south of Cerros del Abrigo to the saddle with the Redondo graben. This was mostly to look at what one of the New Mexico Geologic Society road logs describes as a rare exposure of a Deer Canyon Rhyolite massive flow over tuff in a road cut. The area is also of interest as the meeting point of two medial grabens of the Redondo resurgent dome. The route passes almost directly over the center point of the caldera. And it’s pretty country.

Okay, explanations. Almost immediately after the Valles caldera collapsed, 1.21 million years ago, the floor of the caldera began to be pushed back up by fresh magma injected into the collapsed magma chamber. This produced what geologists call a resurgent dome, which today is visible as Redondo Mountain, Redondo Border, and the hilly country north of Valle Jaramillo and Alamo Canyon. This dome is divided into three sections by Valle Jaramillo, Redondo graben, and Alamo Canyon. These canyons are where the surface of the dome faulted as it was stretched by the underlying magma, and slivers of the surface dropped several hundred feet to produce the valleys we see today.

As the dome began to rise, small volumes of magma erupted through the many faults in the dome. These eruptions first produced hot volcanic ash that formed a thin bed of tuff, then lava that formed massive flows. This is the Deer Canyon Rhyolite. Subsequent small-volume eruptions produced a slightly different rhyolite called the Redondo Creek Rhyolite. Both are present along my planned route. The distinction between the two is that the earlier Deer Canyon Rhyolite contains phenocrysts (visible crystals) of quartz and the later Redondo Creek Rhyolite does not.

So I got to bed early Sunday, got up at 6:00 Monday morning, ate breakfast (organized around a leftover pancake from Saturday), packed a lunch and other supplies in the Wanderpack, and headed out for the Valles preserve in the Wandermobile. I wanted to arrive at or shortly after 8:00 to be sure they would still have back country permits. (They only issue a limited number per day, on a first-come, first-served basis.)

The caldera was fogged in.

This is not unusual. The caldera accumulates cold air, producing a temperature inversion that often leads to the formation of fog or a low cloud layer. This cold air is also one reason why the caldera floor tends to be treeless: The seedlings just can’t take the cold.

On the drive from the gate to the headquarters, I encountered an elk stag.

And vice versa. The elk considered me briefly, then bounded off.

The fog lingered as I got my permit at the headquarters.

I proceeded to my trail head, pausing to look back down the southern leg of Valle Jaramillo towards the caldera and the fog bank.

There’s frost on the ground, which the ranger at the headquarters had told me was the first of the year. But when I arrived at the trail head, I found that the sun was rapidly melting the frost and it was already too warm for my sweater. I greased up with bug repellent and sunscreen and headed out.

To the left are the foothills of Redondo Peak. To the right is a ridge underlain by debris flows that came off the resurgent dome as it was pushed up.

Redondito is just coming into view.

I spotted a rock, probably Deer Canyon Rhyolite, by the trail. It had prominent green vugs of (probably) epidote from hydrothermal alteration. This is a common feature of the Deer Canyon Rhyolite, which likely erupted into an early crater lake.

Since we are on the Valles preserve, the temptation to take this with me must be ignored. Alas, the photograph did not turn out well enough for the book.

Trudge trudge trudge, and a clearer view of Redondito.

Redondito is a knob on the north flank of Redondo. It’s rather a substantial knob, actually, as we’ll see later on. It has the look of a volcanic dome, but it’s underlain by the same Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, as the rest of Redondo, so it’s just a bit of a mystery. And since it’s in the cultural off-limits zone (established out of respect for Native American religious beliefs), it’s probably going to remain a mystery.

From this spot, the first megabreccia ridge is also in view. I visited this some weeks ago but took another picture anyway.

The ridge at the center of the photograph, as well as the knoll just to its left, is underlain by Paliza Canyon Formation andesite. Paliza Canyon Formation is pre-caldera rock, over 7 million years old, that forms much of the rim of the caldera. The block here is a single massive slab that broke off the edge of the caldera as it collapsed and slid across the caldera floor to this point — almost at its center. There are many such slabs of megabreccia in this area, representing almost every pre-caldera formation found in the caldera rim.

The tip of this particular block is partially overlain by very early lake sediments, from the crater laked that accumulated immediately after the caldera collapsed. I’ve taken photographs of these before, but I wanted one more for the book showing that the sediment beds lap onto the megabreccia block.

The megabreccia andesite is the dark rock at the very tip of the ridge. The white beds to the right are the early lake sediments, which were probably bleached by hydrothermal activity in the lake.

I had been hearing elk bugling in the hills to the south all morning. It’s their mating season. There were also tracks in the trail.

And other signs.

“Just what kind of crap are you posting nowadays?”

Some more trudging, and I was approaching the saddle area.

The hill at the end of the valley is underlain by Redondo Creek Rhyolite. The saddle is located just to its south (left).

Redondito grows ever larger.

The trail passes close to an outcrop of Deer Canyon rhyolite. I originally thought this was a debris flow, but the uniform boulders of light rock and the geologic map confirm its identity.

The road begins its slow ascent towards the saddle.

According to the geologic map, this area is a small bog. I’m glad I missed that.

More evidence of elk:

The recently fallen spruce has had most of its branches nibbled off. By now (it was about 11:00) the bugling in the hills had died down a bit.

The road turns north as it ascends.

I wondered if the flat area was the bog marked on my map; if so, it was largely dried up this time of year.

The hill in the background is part of a single massive megabreccia block over a mile long that forms the north rim of Valle Jaramillo in this area. It is one of the two largest such blocks mapped in the caldera, the other being a block of Tshicoma Formation dacite lying east of Redondito.

The road turns back west and begins to ascend more steeply.

None shall pass!

Then south, and Redondito is beautifully framed by the forest.

A couple more jogs, and the exposure I’ve hiked all this way comes into view in the road cut.

Just as described in the road log: Massive Deer Canyon Rhyolite overlying Deer Canyon tuff. Here’s a close up of shards of each:

The shard at left is the tuff, which is a very fine-grained, porous, white rock. The shard at right is the massive rhyolite, which is chock-full of crystals of quartz. The presence of quartz confirms that this is Deer Canyon Rhyolite and not Redondo Creek Rhyolite.

It was only a little after 11:00. I began thinking about hiking further on, to the saddle itself, to get a look down into Redondo graben.

The trail began to open out a little, giving a nice view of the megabreccia ridge to the north.

Then the road widened into a turnout. There were too many trees for an ideal panorama, but I photographed away anyway.

Notwithstanding the foreground trees, this shows just how yuge the megabreccia block is.

The best view of Redondito yet:

The knob east of Tschicoma is yet another megabreccia block, composed in this case of Tschicoma Formation dacite. It’s the other of the two largest megabreccia blocks mapped in the caldera.

Nearby is an interesting outcrop, visible at extreme right in the previous photo. Here’s a better view.

This is an exposure of caldera-fill debris flow deposits. The rock fragments likely came off the caldera walls and slumped onto the caldera floor, where they were cemented together by the ash-rich matrix. There was enough silica in the ash to ensure that this deposit was well cemented.

A photograph of this exposure is included in the New Mexico Geologic Society road log for this area. It’s always kind of fun to match these photographs up.

I found myself hoping the next rise would prove to be the saddle.

Nope.

Nope.

At this point, I was looking at my watch (still well before noon), feeling my aching feet, and wondering if it wouldn’t be more sensible to turn around now. Still, that outcropping ahead looked interesting.

Not sure what this is. The area is mapped as debris flow. But this looks like rock that has been so heavily hydrothermally altered that it has disintegrated into clay. On the other hand, the geologic map shows early lake deposits just uphill, so this might be that as well.

Heck, might as well just commit myself to hiking however far it is to the saddle. Naturally the next rise turned out to actually be the saddle.

I hiked just enough further to get a glimpse down into Redondo graben.

Redondo Peak is to the left behind the dead grove. The ridge to the right is Redondo Border, and Redondo graben lies between the two.

Time to head back. Along the way, I spotted a rather spectacularly colored rock in an area mapped as Deer Canyon Rhyolite.

The vivid green color is likely due to epidote formed by hydrothermal alteration. The rock is still very solid, which rules out certain other forms of alteration. There are visible quartz crystals, as well as transparent lath-like crystals whose identity I’m not mineralogist enough to identify.

This was not the first time on this trip that I had to fight down the temptation to let a little bit of rock find its way into the Wanderpack. But this was on the Valles preserve, so catch and release rockhounding was mandatory.

As I descended to the foot of the saddle, I found myself feeling drawn to the megabreccia ridge north of the valley. It didn’t look like a hard climb, and beyond …

The ridge to the left is the northern end of Redondo Border. The knob in the center of the first frame is yet another megabreccia block, this time of Paliza Canyon Formation tuff over andesite. The mountain just visible through the trees at the right side of the second frame is Cerro San Luis, and the drainage in the foreground empties into San Luis Creek.

At this spot were numerous boulders of obvious Paliza Canyon Formation andesite.

These were weathered off the andesite megabreccia block, which is also now broken by numerous faults.

Continuing down the saddle, I was struck by the view of the Tschicoma Formation megabreccia block near Redondito.

The angle of the sun highlights the rows of logging roads on the peak. Logging in the Valles caldera apparently paked around 1963. Most of the roads are now overgrown, but in places they make an effective network of trails. These are off-limits, as they are in the cultural exclusion zone.

Cerros del Abrigo down the valley to the east.

This mountain was also heavily logged, and the roads are clearly visible in the right lighting conditions from State Road Four in the Valles caldera.

My feet were feeling rather pounded by this point, and so I was very glad to have the Wandermobile come into view.

I later retraced my route on Google Maps and found that I hiked at least twelve miles this day. I don’t think I’ve walked that far in a single day since graduate school. However, the route was level and easy most of the way.

Some kind of dog had been on the trail since the last rain.

Not a large print, but domesticated dogs are not generally allowed in the back country, so this would likely be a coyote or timber wolf. At this elevation, I lean towards the latter.

I was nearing the point where I could cut across a meadow and avoid a long loop of the road getting to my car. However, I had a recollection that there was supposed to be another outcrop of Deer Canyon Rhyolite if I continued along the road, and so I ignored my aching feet and took the longer route. I found that there were numerous obsidian chips and blobs (“Apache tears”) in the road bed.

These may be anthropogenically derived erratics (“stuff brought in by people”; not an official geological term). The road passes near a large borrow pit on Cerro del Medio further south, and that area is famous for its obsidian deposits.

I found my outcrop. I thought.

Turns out this is much too far north; the geologic map has this area as alluvium. Which is not to say that the clasts can’t include a lot of Deer Canyon Rhyolite; there are plenty of outcrops mapped upstream. But not one for the book.

Got to my car. Man, did my feet ache. (The rest of me seemed in pretty good shape.) As I drove out, I found the lighting just about perfect for a panorama of the Valle Grande as seen from the northwest.

Cerros del Medio, the first of the ring facture domes, extends across the first two frames. This erupted a few tens of thousands of years after the Valles eruption 1.21 million years ago, from magma rising through the ring fracture left by the caldera collapse. The south rim of the caldera fills the remaining frames. Pajarito Mountain is on the boundary of the first and second frames, with Cerro Grande to its right. Sawyer Dome is on the right side of the third frame. Between is the saddle through which State Road 4 enters the caldera. These three peaks are part of the Tschicoma Formation, erupted between five and three million years ago. The long mountain in the fourth frame is Rabbit Mountain, thought to be remnant of a ring dome erupted following the Toledo eruption 1.65 million years ago; most of this dome foundered into the Valles caldera. The low ridge to its right includes the northern part of Aspen Ridge, while the peak in the center of the last frame is Los Conchas at the north end of Peralta Ridge. Aspen Ridge and Peralta Ridge are underlain by basalts, andesites, and dacites of the Paliza Canyon Formation, which erupted between about 14 million and 7 million years ago. South Mountain is just visible at the right edge of the panorama; this is the last of the ring fracture domes, erupted about half a million years ago.

I know. I’ve photographed this scene before, and I’ll doubtless photograph it again if Santa Claus brings me the new camera with panorama capability I’m wishing for. But the lighting and weather were just perfect this day.

A little further down the road are some lake deposits from the most recent of the intracaldera lakes, which formed when the El Cajete eruptions blocked the Jemez River.

I know: Not terribly exciting. But this is a significant part of the Jemez story, and so this one is for the book.

I checked out and headed out of the caldera, pausing to photograph the terraces at the west end of South Mountain.

Meh. Too much backlighting, not enough zoom. Not one for the book. But that’s Las Conchas at left, Los Griegos to its right, and of course South Mountain. Los Griegos is the high point of the south caldera rim.

It was barely 2:00. I headed out to Fenton Lake for some photographs of the Otowi Member of the Bandelier Tuff at its finest, and hopefully some thick beds of Tsankawi pumice.

The impressive cliffs are mostly Otowi Member with a layer of Tsherige Member at the top. The Otowi Member was erupted 1.65 million years ago in the Toledo event; the Tsherige Member was erupted 1.21 million years ago in the Valles event. The Otowi Member is overshadowed by the Tsherige Member on the east side of the Jemez, in the Pajarito Plateau, but the Otowi Member is more prominent on the west side, in the Jemez Plateau.

The Tsankawi Pumice is a bed of pumice at the base of the Tsankawi Member; it is found all around the caldera but tends to be thicker to the northwest, which is where we are now. I hoped to get a good photograph of exposures at Fenton Lake, except poor lighting and I’m a tightwad; the lake turns out to be a state park with an entrance fee.

So I headed on up State Road 126, through Bear Canyon

and the fish hatchery

and onto the gravel section of SR 126 in Calaveras Canyon. Where some of the Otowi Member becomes truly impressive.

The entire cliff here is Otowi Member, with no cap of Tsherige Member. Note what looks like a very thick sequence of surge beds making up the lower half of the formation.

I went as far as the summit of State Road 126, saw no Tsankawi pumice, gave up, and headed out.

Along the way I spotted a road cut that features prominently in the geologic report for this area.

The bulk of this road cut is light sandy sediments of the Ojo Caliente Member, Santa Fe Group, which are Rio Grande Rift fill sediments. Here is a close up view of the area to the left.

At bottom and at left is the Ojo Caliente Member. The darker patch of rock at top left is Otowi Member, Bandelier Tuff, as are most of the boulders in the middle layer. Atop this is the Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, with a thick section of Tsankawi Pumice. I had my photograph of the Tsankawi Pumice after all.

So then home, to take care of some chores and rest my aching feet.