Oysters, ammonites, and shark’s teeth

Today was another excursion with the Los Alamos Geological Society, the PEEC, and the Pebble Pups. The destination was two sites in the Mancos Formation that are rich in fossils.

The Mancos Formation was laid down about 80 to 95 million years ago, during the Cretaceous Period, in the Western Interior Seaway. The Western Interior Seaway was what geologists call an epicontinental sea, which is a shallow sea located over continental crust. In today’s world, the ocean level is relatively low, and epicontinental seas are limited to a few areas like the North Sea or the South China Sea. During the Cretaceous, the ocean level was the highest we know of in the geologic record, and perhaps half of North America was covered by shallow seas. The area roughly from Texas through Montana to the Arctic was low ground, due to plate flexure, and so was occupied by one of these shallow seas.

Plate flexure occurs when part of a continental plate is forced down by the weight of mountains formed along its margin. Because the plate is rigid, the area adjacent to the mountains is forced down as well, producing a shallow basin. During the Cretaceous, a tectonic plate called the Farallon Plate was subducting beneath western North America, throwing up a range of coastal mountains (the early Sierra Nevada) whose weight caused plate flexure and created the basin flooded by the Western Interior Seaway.

The Mancos Formation is ocean sediments laid down in the Western Interior Seaway. Much of the Mancos Formation is black shale, mud that settled to the bottom under conditions of poor oxygenation, and is devoid of fossils. But a few beds of the Mancos Formation were formed under conditions of high oxygenation and contain abundant fossils. Our trip today took us to two such locations.

I got up at 6:30 (early for a Saturday, but still sleeping in compared with a regular work day), feasted on the usual breakfast, packed my geology stuff and a pack lunch in my backpack, loaded the car, realized I had forgotten the cell phone, went back in for it, found it was not in its usual place, found where my son had left it, went back out to the car (now in a slight rush), realized I had loaded Clownie the Wonder Car out of sheer habit and that he didn’t have enough gas even if he was in any shape for a trip out of town, moved everything into the Wandermobile, found that the Wandermobile was down to half a tank of gas, decided this would get me to the rendezvous, and headed on out. Yeah, sometimes it becomes hectic like that.

The first part of the trip was along State Road 4 from my home in White Rock to Jemez Pueblo. This is well-traveled ground for me and I was concerned about the time, so I did not stop for photographs. I needed to be at the intersection of U.S. 550 and State Road 279 before 10:00, and since I had not timed the drive before, I had to give myself leeway. Nevertheless, with so much fresh country between Jemez Pueblo and the rendezvous, and with the schedule looking pretty good once I was through San Ysidro, I indulged in a couple of stops for pictures.

The first was of cliffs topped with Todilto Formation.

I’ve seen these formations before, in the northern Jemez, where they are fairly spectacular at Mushroom Canyon; but they were worth photographing again here, for a couple of reasons. First, the Todilto is considerably thicker here. Second, the Entrada Sandstone found beneath the Todilto Formation is a pale white rather than the red, white, and yellow found north of the Jemez. Both formations are Jurassic formations, the Entrada Sandstone deposited around 160 million years ago and the Todilto Formation in a relatively brief period of time shortly thereafter. The Entrada Formation was laid down as a dune sea, while the Todilto Formation was probably laid down in a barred basin, which was an extension of the ocean with a shallow bar across its mouth. The bar allowed sea water to enter but trapped denser, saltier water produced by evaporation from the surface of the basin. Eventually the deeper water became so concentrated that beds of gypsum began to precipitate out of the water. Thus, the Todilto Formation has a base layer of limestone and an upper layer rich in gypsum. This is mined in several locations in New Mexico.

At the bottom of the cliffs is a reddish layer of the Triassic Chinle Group. This is mostly mudstone laid down in the delta of a large river, the Chinle River, that may have run all the way from the southern Appalachians to Nevada.

Further down the road, some more cliffs were just too good to miss.

The same formations are here as in the previous photograph, but there is a prominent yellow bed in the Entrada Sandstone in the first frame that pinches out in the second frame. A bed is said to pinch out when it thins to nothing, leaving the beds above and below in contact.

A little further on, I came into an area of sandstone somewhat resembling the Dakota Formation of the northern Jemez. I thought it worth a photograph.

There are a lot of sandstone formations in this area, so I could not be sure this was Dakota Formation, particularly since the colorful beds to the right are not typical of the Dakota Formation. After I got home, I checked the coordinates against the geologic map and found this was Morrison Formation, which lies atop the Todilto Formation in this area. I might have guessed; the Morrison Formation is famous for its varied hues. However, the Morrison Formation is scanty in other parts of the Jemez, and the only beds I’ve gotten close to are much less well cemented than these.

That just makes it one for the book.

To the left was a nice view of Cabezon Peak.

Cabezon Peak is a volcanic plug, formed by lava that solidified in the vent of a volcano. The remainder of the volcano was softer rock and has eroded away. This plug is geologically young, being part of the Mount Taylor volcanic field to the south, as is Mesa Chivato visible on the skyline behind Cabezo Peak. Mount Taylor itself just peeks over Mesa Chivato on the left side of the photograph.

Our tour leader on this trip, Patrick Rowe, told us that Cabezon means “big headed” and reflects an Native American myth that the peak is the head of a slain giant and Mesa Chivato is a hardened pool of his blood. (And if you think that’s gruesome, I have some Greek myths and one or two Shakespeare plays for you …)

I arrived at the rendezvous at about 9:45 and found several cars there already.

While waiting, I notice the road cut across the road. (Geologists always notice road cuts; they’re in love with the things.)

The reason why is that road cuts expose a nice fresh cross section of the local rock beds. I had glanced at the geologic map for this area and it seemed like Mancos Formation everywhere, but I was used to the Mancos Formation being a dark shale (in fact, I’m using to calling it the Mancos Shale) whereas this is a relatively light, thinly bedded, but well cemented sandstone. I checked the map when I got home; yup, Mancos Formation. It’s always rich in clay but sometimes with a fair amount of sand or lime; this is a sand-rich bed.

I did not see fossils.

The road had barbed wire on both sides, because here it is crossing tribal land; this made it awkward to deal with some excess liquid I had no further use for. I felt more awkward still when I got snagged by a barb as I tried to work my way through the fence, and some sweet young thing came by and helped me through. Awkward, but grateful.

Patrick Rowe pulled up, talked briefly about the geologic setting, and off we went. By this time it was a sizable group.

We drove through San Luis and the road turned to dirt, which took us southeast and up and down several ridges. There was stuff I would like to have photographed, but I was preoccupied keeping up with the convoy. We finally arrived at what is called the Windmill Site.

Yes, there’s a windmill. No, I didn’t think to photograph it. In fact, I spent the next hour concentrating on digging up shards of limy shale looking for fossils. This area is known for its “oysters” (Bruce Rabe tells me that a lot of the Cretaceous “oysters” may not be), ammonites, and turitella gastropod shells. I did not see any gastropods, but I found some “oysters” and ammonites.

The fossil at left is likely Inoceramus, which is very common in Cretaceous rocks of the Western Interior Seaway. It resembles a modern oyster but paleontologists now believe it is a distinct lineage of mollusc.

This is an ammonite cast, or so I’m told.

A slab of sea floor:

The photographs are hard to get right. I really need something other than a cheap tourist camera with contrast autofocus. The autofocus had a hard time finding anything in these rock slabs to latch onto, and tended to focus on the wood grain of the table beneath instead. I tried using some Geological Society of America focus cards, but this helped less than I expected.

An interesting thing I noticed is that some of the “oyster” shells are preserved:

whereas there were no examples where the actual shell of an ammonite was preserved, only casts. This may be because the shells are chemically different. “Oyster” shells are calcite, while ammonite shells are aragonite. Both are calcium carbonate minerals, but calcite is more stable than aragonite. Aragonite dissolves below a certain depth of ocean water, called the aragonite compensation depth, while the calcite compensation depth is considerably greater. I find myself wondering if the floor of the Western Interior Seaway managed to get below the aragonite compensation depth at some point, dissolving all the aragonite ammonite shells while leaving the calcite “oyster” shells.

After the hour was up, we all gathered together and prepared to convoy yet deeper into the badlands. I was a bit concerned about my gas; I had started with a little over half a tank and I was now down to a quarter of a tank. Patrick assured me that that should be enough to get me to the nearest gas station even with the drive to Shark Tooth Ridge. It was another interesting drive where I regretted not being able to stop for pictures until we arrived at the site.

This ridge has a rather steep escarpment to the south, caused by a very resistant bed of sandstone that has been interpreted as a beach deposit.

You can see the sandstone bed forming the escarpment. This extends for a considerable distance to east and west. In the background is Cerro Cochino, another volcanic plug of roughly the same age as Cabezon Peak.

The sandstone bed is full of fish teeth, including the occasional shark tooth. These can be hunted by digging and sifting the sediment atop the sandstone bed near the escarpment edge.

The rounded tooth at top is from a species that crushed shells for a living. The others are from large carnivorous fishes. I did not find a shark tooth, which would have been more blade-shaped with a serrated edge. Patrick Rowe suggested that the light was not ideal for spotting teeth, it being late in the year and the ideal being for the sun to be nearly overhead. I imagine it gets rather hot out there at that time of year.

At top is a single calcite crystal that I dredged up. Calcite is the principal cementing mineral in the sandstone. The crystal is quite irregular, but you can tell from the uniform reflection off of cleavage planes that it is a single crystal.

And note that the focus is off. My camera has no manual focus capability and I could not get the autofocus to behave well. I’m hoping there will be a new and better camera in my stocking this Christmas, but I’m not sure I’ve been a good boy this year.

Shark Ridge is not far from Cabezon Peak.

My Ansel Adams image for the day. Volcanic plugs are photogenic, aren’t they?

It turns out there is no published quadrangle map for this area, but from road logs, I get the impression that the lighter tan bluffs in the foreground are Mancos Formation topped by Lookout Point Formation sandstone beds. The latter is an upper Cretaceous formation.

One more of Cerro Cochino.

Also prominent nearby was Cerro de Guadalupe.

It was time to start heading out.

The road out passed very close to Cabezon Peak.

Ahead were mesas topped by another resistant bed; without a good geologic map, I can’t guess which.

Note that the road is usually fairly well maintained. Our convoy included several passenger vehicles, and I would not hesitate to drive this road in good weather. (Wet weather is another matter.)

And to the northwest on the skyline is the Sierra Nacimiento, at the western edge of the Jemez Mountains.

We passed close to the mesas on the road out.

My guess is Lookout Point sandstone over Mancos shale.

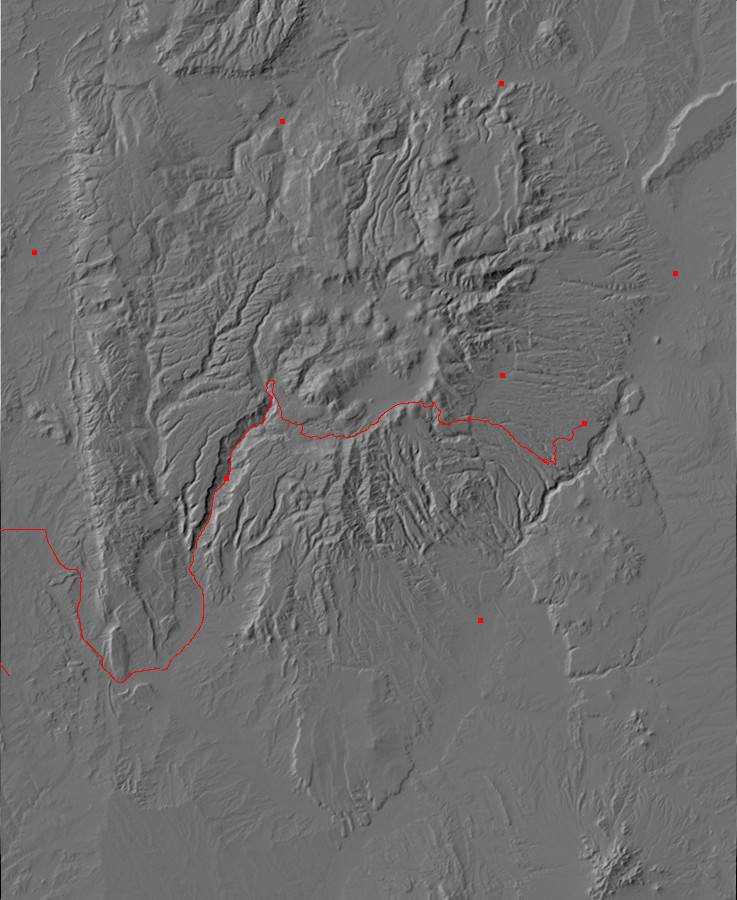

As I approached U.S. 550, I paused for a panorama for the book.

Unlike most of the Jemez, which is a volcanic pile resting on Paleozoic to Mesozoic sedimentary beds and Tertiary rift sediments, the Sierra Nacimiento is what geologists call a Precambrian-cored Laramide uplift. In other words, it is a huge block of crust pushed upwards during the Laramide Orogeny, which began at the end of the Cretaceous and continued at least to around 30 million years ago. Erosion has since stripped the upper layers of this block of crust to expose Precambrian basement rocks that were once far below the surface. The high point in the range, at the left side of the last frame, is Pajarito Peak, which is mostly underlain with gneiss with a quartz monzonite cap. These beds are around 1.6 billion years old. The range north of Pajarito Peak is underlain by the Joaquin Granite, a very large pluton (intrusive body) emplaced around 1.4 billion years ago.

A prominent feature on the drive back is Cuchilla Blanca Hill.

The hill is topped with Todilto Formation which dips sharply to the north (left). Underneath is Entrada Formation, and beneath that is Triassic upper Chinle Group red beds. The distant ridge to the right is underlain by Agua Zarca Member of the Shinarump Formation, and the ridge partially hidden behind it is underlain by more Precambrian gneiss.

A little further south one comes to Red Mesa.

This is another crust block thrown up by Laramide compression, but this block retains most of the Paleozoic and Mesozoic beds. At top is a cap of Agua Zarca Member, which is a very resistant sandstone that caps several beds in the western Jemez. Immediately beneath is a brown band of Bernal Formation. Both are Triassic formations. The remaining formations are Permian: the light-colored Glorietta Sandstone, the orange Yeso Group, and the red Abo Formation.

The white area at the base of Red Mesa is Jurassic Morrison Formation over Todilto Formation. These are much young than the beds behind them, and show that there is a major fault, the Pajarito Fault, along the west face of Red Mesa. It was along this fault that much of the Sierra Nacimiento was thrown up.

I stopped at San Ysidro for gas, then headed back through the Jemez. As I neared home, I took one more photograph, of the San Miguel Mountains at sunset.

I had meant this to be one for the book, but the lighting isn’t good; the canyon in the foreground, upper Frijoles Canyon, is dramatic in better light but is in shadow here. I’ll have try try again from this spot in early summer.

And home.

Pingback: Young men and old teeth | Wanderlusting the Jemez

I enjoyed reading the article Patrick Rowe I had a question. I have a friend that found a bunch of teeth not sure if they are shark or carnivorous fish. I’m a shark tooth collector and I’d love to send you pics of her finds she sent me. Thanks Earl Ray Mars III

Hi Earl,

Unfortunately, Kent Budge passed away on November 10, 2022. I hope you will continue to enjoy his Wanderlusting posts.

Cindy Budge (Kent’s wife)