Wanderlusting Truchas

So there was enough rain yesterday that I decided not to go to the effort of trying to find a hiking partner, and decided instead to follow another New Mexico Geological Society road log. This one was to the Truchas area, and dated back to 1979. It had the merit that the most interesting part of the route would not be in high terrain likely to be covered by snow. It also had the merit of including a very distant deposit of Guaje Pumice, perhaps the most distant from its source in the Jemez that I’ve come across in a road log. I had followed this log once before, but only cursorily, being mostly interested in some metamorphic rocks up in the mountains at the end of the log.

I woke up to a crystal blue sky. It would remain a beautiful day, though with occasional scattered clouds. My first stop was an impromptu: I was struck by how beautiful the San Ildefonso area was as I drove east on NM 502, and decided to try my hand at a panorama using my new camera and a tripod, with the camera taking individual frames to be stitched together with Hugin. Wow:

This was with the default settings of Hugin: No monkeying with vignetting or exposures. It seems that part of the reason I had to monkey with a lot of my panoramas with the old camera is that it was a crappy camera taking crappy pictures. The images from my new camera, on inspection, show no sign of vignetting and show remarkably little corner distortion.

The only thing is that it looks like I did not get quite level with the horizon. This is a bit odd, because I took some pains with the bubble level on my tripod to get this right. But then the road really does rise to the right, so perhaps this isn’t wrong. On the other hand, Hugin lets me tweak the levelling:

That seems better. It does raise the question whether this is a digital manipulation that is somehow less “authentic.” It’s a good question, but I think the answer is No. If I understand how Hugin works, I’ve simply modified how the images are projected onto the sphere and then onto the plan, and no projection is more “true” than another.

My conscience placated, I’ll move on. In the other direction is the Cerros del Rio, which was not suitable for a pan (too close to the sun direction) but worth an artsy shot.

I’m not sure this is one for the book, since the shadows are rather deep, but its fun to look at. Notice the total absence of vignetting.

I proceeded to my favorite knoll at Jaconita to try yet another pan of the Sierra de los Valles. I swear, this is the keeper:

That’s with moderate zoom.

Seeing as I was there anyway, I took another one of Los Barrancos to the north as well:

To quote one of my favorite philosophers: Hokey digital manipulations and ancient equipment are no match for a good camera at your side, kid.

I took the exit to Espanola and almost immediately took another exit to Nambe. At this point I began following the road log. The first attraction was the Nambe church:

Nambe Pueblo is a Tewa-speaking community first settled in the 14th century. A church (with the proper name Sagrado Corazón de Jesus) was first built here early in the Spanish era, but burned to the ground in 1946, so the current edifice is fairly modern.

The graveyard is right next door, and probably is as old as the original church. However, I saw dates as late as 2007 on headstones near the fence, so it appears to still be in use. It was about as cloudy at this point as it got all day, and I tried to do something artsy with the shadows:

Meh. I was thinking bright background, graveyard in shadow, would be a nice effect, but not enough bright background.

On this one I tried the opposite effect, with dark background and bright graveyard, but the background hills are too bright.

Proceeded on, and stopped for a road cut full of Nambe Member, Tesuque Formation.

The Tesuque Formation is part of the Santa Fe Group, which includes all the rift fill sediments of the Rio Grande Rift. The Rio Grande Rift is a crack in the Earth’s outer crust running from central Colorado to around El Paso, where it merges into the Basin and Range Province. The crack or rift has been partially filled in with sediments from the surrounding highlands, and these have in turn been reworked by the Rio Grand, which runs most of the length of the Rift. The whole region has experience recent (in geologic terms) uplift which has caused increased erosion, exposing many of the rift fill formations.

The Nambe Member is the oldest member of the Tesuque Formation, which was deposited around 16 to 20 million years ago. This portion is part of Lithosome A, which is the part of the Tesuque Formation formed from feldspar-rich sediments eroded off the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to the east. The feldspar gives the pinkish color to the outcrop.

More Nambe Member up ahead:

The Nambe Member seems prone to form rolling hills rather than sharp cliffs.

Past the road cut, I could see cliffs of the Skull Ridge Member to the west.

The Skull Ridge Member is the next oldest member of the Tesuque Formation, with an age of around 16 to 13 million years. It tends to form cliffs like these, probably because it contains numerous ash beds to provide cementing silica. The ash beds predate the Jemez volcanic field, or at least the exposed portions of the Jemez volcanic field, so their origin is uncertain. The cliffs shown in the second photograph may be part of a feature called the Red Wall by geologists who have worked in this area; I’m not entirely sure but it’s reddish, it looks like a wall, and this is roughly the right area.

Camel Rock, familiar to most residents of northern New Mexico, is eroded out of the Skull Ridge Member.

Roadside attraction:

Here some resistant beds cap softer sediments beneath.

Time for another panorama from a favorable spot:

In the middle distance is (I think) the Red Wall, underlain by Skull Ridge Member. To the right you can see a thin white bed capping the cliffs. This is probably White Ash #2, a layer of volcanic ash of uncertain origin. There are glimpses of another white ash bed at the base of the cliffs, which is probably White Ash #1, which marks the boundary between the Nambe Member and the Skull Ridge Member. White Ash #1 came from an eruption in Nevada 15.86 million years ago.

On the skyline we see the Sierra de los Valles at left, Tschicoma Peak left of center, Lobato Mesa right of center, and the Rio Chama valley north of Lobato Mesa.

Further down the road, the road log describes a charcoal bed about a foot below the surface level in a road cut. I think I saw it but it was so badly backlit by the sun that a photograph was pointless. However, this was a good place to check my blood sugar (120 — a touch high) and eat my breakfast orange. Except that the blood sugar being a touch high suggested I ought to wait a little.

Closer to the mountains, the Nambe Member starts to contain more coarse conglomerate beds.

This is a very common pattern in sedimentary beds. The coarser material is found nearer the source rocks and the finer material further away. This can be a very useful clue when reconstructing paleotopography for more ancient periods in the earth’s history, where sedimentary beds are all that are left of the original landscape. Thus, the tendency for beds of the Triassic (between 200 and 250 million years ago) to be coarser north of the Jemez than south of the Jemez is a clue that the sediments originated in a highlands near the Colorado border.

There was a convenient knoll near here for some more landscape shots.

From here I proceeded through the little village of Cundiyo. Just past the village was a parking area and a trailhead. The road log claimed there was migmatite down the trail; well then. I had very hastily explored this area once before, but missed the trail. I needed to burn off some of that sugar anyway before eating my orange, and I needed to dispose of some liquid waste. Cindy and Mom (who worry about me venturing into the wilds alone), take note: The trail had the look of fairly heavy use, and in fact I ran into a couple of parties out fishing along the way. I was not venturing deep into the wilds by myself.

The trailhead.

The canyon leads into an area of metamorphic rock, shown on my geologic map as XYu. This is code for “undifferentiated Proterozoic igneous and metamorphic rocks (likely Mesoproterozoic to Paleoproterozoic)”, which in turn means “a confused and undecipherable mess of basement rock somewhere between 1.4 and 2.5 billion years old.” Since no rocks in this part of New Mexico have a radiometric age in excess of 1.8 billion years, we can narrow it down a little. Still. What I would see in the canyon would indeed be a nearly indecipherable mess of highly metamorphosed very old rock.

Like this.

This is a vaguely granite-like rock, but with lots of muscovite mica in it. This suggests a source material rich in aluminum, such as clay. We may be looking at a very ancient mudstone that has been baked and deformed almost beyond recognition.

Here is pink granite-like rock underlying darker, more iron-rich rock.

The trail went on a considerable distance.

But since I was alone this trip, and had promised Cindy that I would not go far off the road, it was time to turn back. On the way back, I took photographs of good migmatite outcrops I had seen going out. (If you know you will be returning the same way, I figure it’s better to hold off on most of the photographs on the theory that something even better may be just around the bed.)

Migmatite in an outcrop:

The migmatite is the darker rock (the melanosome) with ribbons of ligher rock (the leucosome.) Many geologists interpret a migmatite as rock that was brought to the melting point, with the leucosome representing the liquid magma separating from the residual solid melanosome. Many migmatites are located on the boundaries of large granite bodies, which tends to support this interpretation, although it’s also possible the leucosome infiltrated the melanosome rather than being extracted from it.

Here’s a closer look, with car keys for scale.

Here‘s a boulder with some very nice twisty ribbons of leucosome.

I walked back to the car and headed out. The road ascended onto the Santa Cruz surface, a former erosional surface now deeply cut by valleys due to regional uplift.

The flat ancient erosional surface forms the skyline. The road cut to the right shows the contact of the gravel surface with the underlying Tesuque Formation.

Around the bend* and a good spot to do a panorama of the badlands northeast of Chimayo.

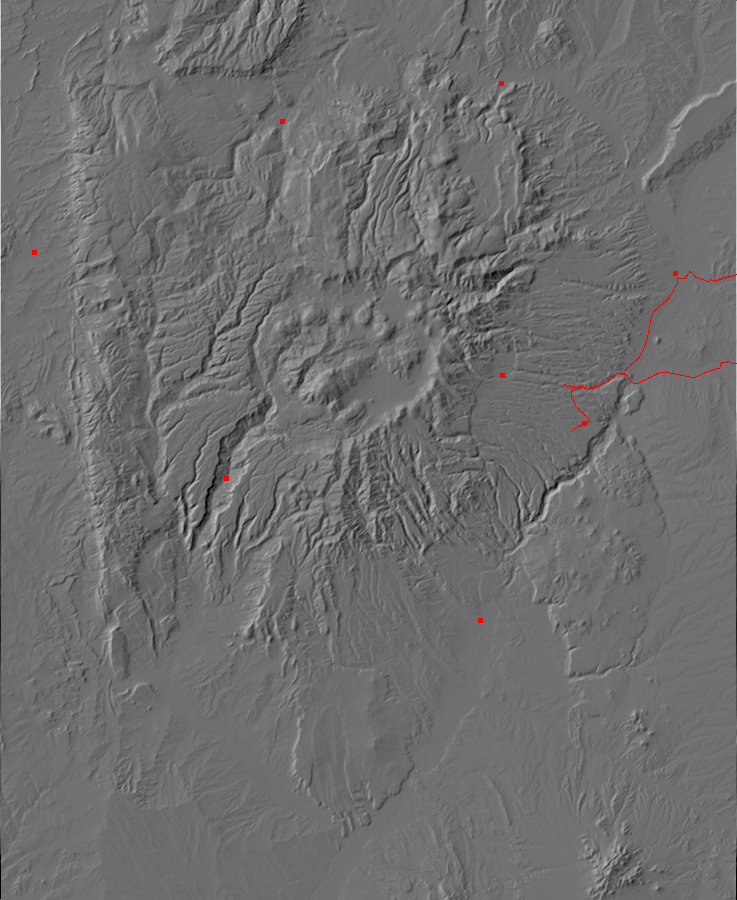

The road headed northeast onto the Truchas surface. I was mostly interested in finding an alleged borrow pit in a bed of Guaje Pumice, interesting for two reasons: First, the Guaje Pumice originated in the Jemez 1.65 million years ago, at the start of the gigantic Toledo eruption, and it would be way cool to photograph some of the pumice from the eruption this far away. Second, according to the road log, the pumice collected in the head of a gully in the Truchas surface, showing that the surface already existed 1.65 million years ago.

Truchas is the setting for the novel, Red Sky at Morning. This was turned into a movie when I was still quite young, memorable to me only because it was the first “grownup” movie my parents took us to. I vaguely recall the dare to touch the dead cow, a Hispanic man with a chihuahua hanging out of his zipper, the eccentric artist with the sculptures on the hill, and (spoiler alert) the main character’s father, who was a captain fighting in Italy at the time (World War II) , being killed by stepping on a mine. I don’t remember there being any discernible plot.

Navigation got a bit tricky on this leg. The exit to Cordoba popped up a mile or so sooner than I expected from the road log; it’s from 1979 so maybe things have changed? Yes. I came across the Truchas cemetery given as another navigation point in the log; great, 0.6 miles to the borrow pit. The road log placed this to the right (and, to leave no doubt, specified that this was east) of the road, but when I got to the indicated mileage, the only thing to the right/east was a big canyon.

Well, shucks, and other comments.

There was what looked like a big borrow pit on the west side of the road at about that mileage, but no obvious pumice. Just a big road sign welcoming me to Truchas. I continued down the road to where I entered the town limits; naturally, this was also a checkpoint in the road log, so I turned around and worked the mileage back. Found myself at the same spot again, with the same canyon to the east and the same old borrow pit on the wrong side of the road.

Took a picture, just in case.

Got out and looked. If there had ever been any pumice here, it had all been borrowed, and I had a feeling it wasn’t going to be returned any time soon.**

The road log was quite old, 1979. I wondered if the road had moved, and had once run to the west of this pit. Sure enough, there was an older road to the west. I explored down it, missed a sharp turn, and wound up on a muddy unpaved road in the middle of nowhere. Still, it seems clear that this was the main road in 1979 and this was indeed the borrow pit that used to have Guaje Pumice in it. Perhaps in an upper area I didn’t spot from the road.

I trekked on in search of ash beds of the Perlette Ash. These beds are mostly known from the Great Plains and are thought (from chemical evidence) to have originated in supereruptions in the Yellowstone area. It’s kind of interesting that some of the ash would have survived here. Alas, the road cut in question was covered in snow. I figured this was the signal that I had hit the useful limit of wanderlusting in February and it was time to start heading home.

I decided I would head home through Chimayo, for variety and because I had never seen the famous Catholic shrine there. I paused to photograph a very large earthwork dam across Arroyo Largo north of the road. The dam is for flood control; Arroyo Largo was notorious for flash floods sweeping on down the Santa Cruz River valley before the dam was emplaced.

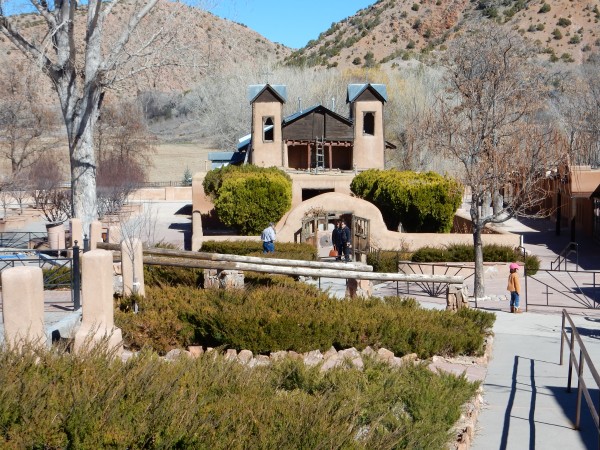

And Chimayo. This is a very popular site for pilgrimage during Holy Week, with devout Catholics walking quite large distances to the shrine. I’m not sure I understand all the cultural context, but it seems to be more a thing with Hispanic Catholics than Anglo Catholics. The legend is that a wooden crucifix was unearthed here and a succession of miracles followed, and the chapel was built over the site in 1816.

I tried to get a photograph without being disrespectful. There’s ample parking but it’s some distance away. I tried photographing as I drove past, but that didn’t work, so I went ahead and parked, walked to a good vantage point, and unobtrusively took my photograph. Not because there was any indication photography was banned; just out of a general sense of not wanting to intrude on another faith’s holy place.

Perhaps I shouldn’t have been so worried. There was a “Holy Chimayo Chile” shack just down the road, with a crude portrait of Christ, and crowds of other vendors and sellers of various sorts. It reminds me of how a newly called leader in my own church, giving his maiden talk in our General Conference, coined the term “ponderize” as a portmanteau of “ponder” and “memorize” to encourage a particular approach to studying scripture. Sure enough, almost within minutes of his talk, advertisements for “ponderize” cards and posters and even jewelry popped up on the Internet at sites favored by Mormons. Bottom line is that the new leader had practiced his talk on some family and friends, and his brother spotted a business opportunity.

I imagine the next family reunion was awkward.

I headed on home, in something of a rush because I was ready for lunch but had forgotten to bring a spoon to eat my sack lunch with. I did pause long enough to try my hand at another panorama from the Clinton P. Anderson overlook.

Here’s my previous best:

The new one definitely is more seamless, but it seems a bit washed out compared with the old one, which seems more “alive”, if you will.

And from there, home.

*Why, yes. Yes, I am.

*A borrow pit is a kind of small quarry where loose material (sand or gravel) rather than solid rock is extracted, typically for road construction or other civil engineering.