Circumwanderlust

I have a tradition of going on an especially grand wanderlust to celebrate my birthday each year. I try to pick somewhere close by but which I’ve never been before. For example, last year I visited the Cerros del Rio, which has been right across the canyon from my home most of my life, but which I had never visited.

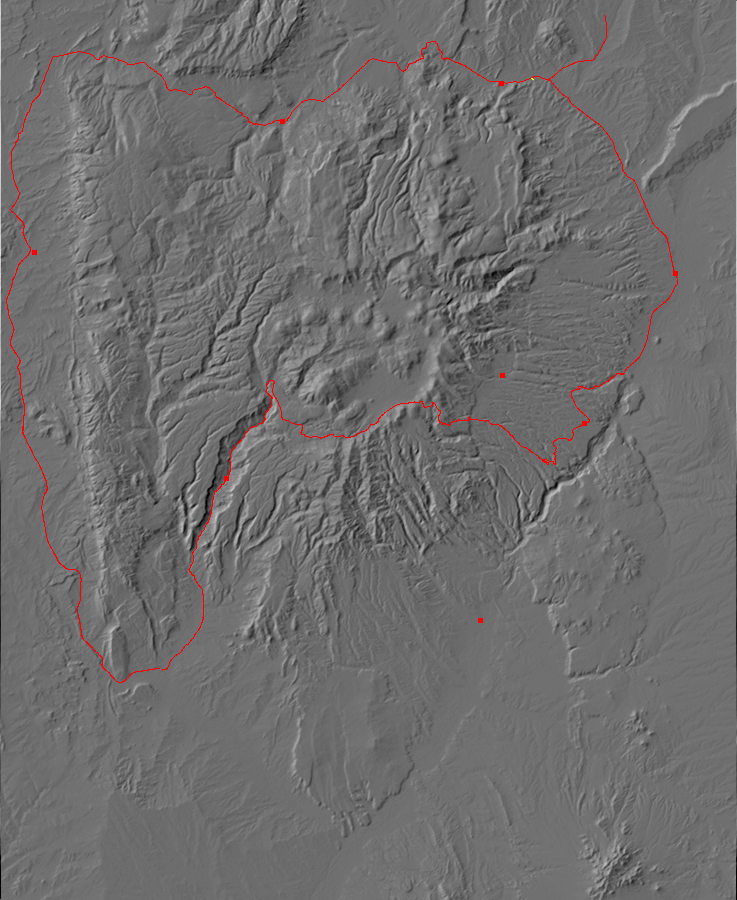

This year I decided to circumnavigate the Jemez Mountains. It turns out that I have traveled every road along the Jemez loop, though one part of the loop is on a road I haven’t traveled in 40 years. I therefore planned a little jog off the loop, to take me to completely pristine ground, just to maintain the tradition.

So after getting plenty of sleep the night before, and having a hearty breakfast, and packing up my equipment and a sack lunch, I headed out of White Rock and in the direction of Abiquiu. This first leg is familiar ground, and I had no particular stops planned; but the light seemed particularly good for photographing Battleship Mountain with the new camera.

One of the nicest things about the new camera is that it has decent telephoto capability.

This nicely shows the rock column in this area. The lower red beds are Chamita Formation of the Santa Fe Group. This is rift fill sediment, which accumulated in the Rio Grande Rift between five and ten million years ago. The pinkish color suggests that these sediments are rich in feldspar and came from the Sangre de Cristo Mountains to the east. Geologists who have studied the rift fill formations in this area call this Lithosome A. I don’t know off-hand which member of the Chamita Formation this would be; possibly Cuertales. If all the names bewilder you, don’t feel bad; the terminology for all the Santa Fe Group beds in the Espanola Basin has become exceedingly complex and sometimes bewilders me. It’s enough to know that these are rift fill sediments around 5 to 10 million years old that came off the Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

The light bed halfway up the mountain marks the base of the Puye Formation, which is a thick sequence of grayish, ash-rich beds formed from lahars and debris flows that came off the Jemez Mountains to the west between 5 and 2 million years ago. The pinkish cap on the very top of the mesa is Bandelier Formation ignimbrite. This is mostly Tsherige Member, from the Valles eruption 1.25 million years ago. However, if you click to get the full resolution image (as you may do with most images at this site), you will see than there is a thin bed of Otowi Member, from the Toledo eruption 1.61 million years ago, to the right of the small cave at the base of the Bandelier Formation cap. It’s separated from the Tsherige Member by a notch.

An ignimbrite is a rock formed of bits of volcanic glass produced when very viscous, silica-rich magma with lots of dissolved gas reaches the surface. The magma basically disintegrates into tiny fragments of red-hot glass suspended in hot gas, which flows rapidly across surrounding areas before the glass fragments settle onto the surface to form the ignimbrite.

I headed on up towards Abiquiu, enjoying the scenery and the occasion but feeling no great need to stop for pictures; this is familiar ground. The light was particularly good for viewing Lobato Mesa, but I could not find a really good place to pull over. Just before reaching Abiquiu, I took the turn north onto Highway 554. This would be my nominal virgin territory for the day; so far as I can recall, I’ve never been this way before. The road afforded some nice views of Sierra Negra, but I have several photographs of this mountain already. I was more interested in a supposed fluorite mine not far up this road, and in the El Rito tuff beds.

I never did find the mine (my directions were vague, and vaguely recalled) but I did find the El Rito tuff beds.

The darker rock is a basaltic tuff, formed from bits of silica-poor lava thrown out by an eruption. Basaltic tuffs rarely if ever form the vast outflow sheets you see with rhyolitic tuff, such as the Bandelier Formation. The silica-poor lava does not hold onto its gas content long enough to move far from the vent. This particular tuff was erupted in a small eruption some 15.3 years ago, based on potassium-argon dating of a basalt bomb embedded in the tuff.

I don’t think I’ve ever explained potassium-argon dating here. The basic idea is that most rock contains some potassium, and one of the isotopes of potassium, 40K, decays with a long half-life to either 40Ca or 40Ar. Calcium is abundant in most rocks, but argon is an inert gas that readily escapes from molten rock. Thus molten magma will normally contain very little argon. However, after the rock solidifies, argon produced by decay of potassium is trapped in the rock. By melting the rock in a vacuum and measuring the amount of 40Ar given off, and comparing this with the amount of potassium in the rock, one can estimate the time since the rock was last molten. The measurement is a bit delicate, and one must correct for any contamination of argon from the atmosphere (argon makes up about 1% of the air we breathe), but since atmospheric argon includes a small amount of 36Ar, one can measure the two isotopes (using a mass spectrometer) and subtract off the atmospheric contamination.

I retraced my path, decided there was still a nice panorama to be taken of Lobato Mesa, found a knoll, and tried setting up my tripod. No go; the ground was soft and far from level and the tripod didn’t clear a nearby fence. So I tried a panorama by hand.

Not bad. It seems like with the old camera, it was hard to get a really good pan; with the new camera, it’s hard not to.

Lobato Mesa is at center. Peeking above it, just right of center, is Polvadera Peak, the third highest point in the Jemez (after Tschicoma Peak and Redondo Peak.) At far right in the distance is Cerro Pedernal. The mesa in the middle distance just left of Cerro Pedernal is Abiquiu Mesa. The unnamed mesa in the middle distance left of center is not a lava-capped mesa, but is a remnant of an erosional surface — the old floor of the Rio Grande Valley, perhaps half a million years ago.

I got back on the highway to Abiquiu and drove to the Poshuouinge ruins. I had visited these once before with Bruce Rabe but had not thought to take pictures. The best vantage point is reached via a short hike from the parking area.

I paused along the way for a big basalt boulder that caught my attention.

What’s distinctive is the two patches full of bubbles. Most likely these are bits of gas-rich magma that solidified early and became solid inclusions in the still-liquid magma that eventually cooled to form the rest of the boulder.

Further up the trail, the terrace top came into view. One could see the mounds marking the old ruins, as well as a number of signs describing the site, warning visitors not to leave the trail, and quoting the Antiquities Act, which protects artifacts on public lands. I briefly got off track, following a trail along a fence south of the ruins that seemed well traveled but went nowhere. I finally bushwhacked up the hill to the tourist lookout plainly visible above, wondering where I had missed a turn. There was signage here:

Rather than parrot the information, I’ll invite you to click the image for the full resolution version.

There was nice flat ground for a tripod, but the sign got in the way of the panorama. I ended up doing yet another by hand.

Not bad, but I’m starting to think I may want to invest in a taller tripod.

I mentioned that the ruins are on a terrace. This is yet another kind of erosional surface, formed close to a river in a level river valley — in this case, the ancestral Rio Chama. The same terrace level is visible just across the valley. More distant, at the foot of Sierra Negra at the center of the panorama, is another remarkably level erosional surface at a higher level. This was formed in a side channel of the Rio Chama earlier than the the lower terraces. It’s hard to get good estimates of ages of these surfaces, but the higher, older surface is probably about half a million years old. Sierra Negra behind it is capped by a basalt flow that has been dated at 4.5 million years old, showing the age of the surface on which the flow erupted, clear at the top of the mesa. (The rest of the surface has long eroded away.) Been a lot of erosion here in the last five million years.

When I was here with Bruce Rabe, we did a lot of speculation of what the original buildings looked like. We wondered then, and I still wonder, if the not-very-healthy-looking tree right of center marks a buried kiva, or ceremonial room.

I took one more photo from the overlook, a telephoto shot of tilted beds of the Abiquiu Formation near Sierra Negra. Alas, I didn’t use enough telephoto, and the picture didn’t turn out well. But I did get a photograph of a dry arroyo west of the terrace as I hiked back.

I know: So? This one is for the book. It’s a very nice example of the kind of dry arroyo that becomes very wet indeed during heavy rain. With their extremely flat sandy bottoms, they’re an important landform in the Jemez area.

On the road again, pausing for a bit of local culture.

This is the Plaza de Santa Rosa de Lima, the heart of the ghost town of Santa Rosa de Lima. The church was apparently in use until the 1930s and is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Nearby, the town of Abiquiu, outside the original genízaro merced, has become somewhat gentrified, and there is a bed and breakfast very close by.

Ah, some history. The Spanish word genízaro has the same roots as the English janissary, used to describe slaves (usually Christian boys) under the Ottoman Empire who gained some measure of freedom and considerable social status by converting to Islam and becoming elite soldiers of the Turkish Army. The genízaros were native American boys (mostly Navajo) enslaved by the Comanche and sold to the Spanish as household servants or shepherds. They were indoctrinated in Catholicism by their Spanish masters, gained some measure of freedom, and eventually formed communities of their own, in which there was extensive intermarriage among tribes and with the Spanish. At Abiquiu, the genízaro community was awarded its own land grant or merced by the Spanish governor. The merced is still a recognized legal entity today. The Abiquiu merced owns the northern part of Mesa Alta, which I have found is very well maintained, even in comparison with the adjacent National Forest lands. And, yes, they still raise some sheep, though cattle is more common now.

I proceeded on to Abiquiu Reservoir, stopping at the visitor’s center for my morning sugar check and orange and a pit stop. To the east, an engineering road descended through a road cut with striking cross bedding.

Cross bedding describes a rock bed in which large beds lying at one angle are composed of smaller beds lying at a different angle. They’re formed by wind blowing sand across a dune or water carrying sediment across ripples on the bottom of a river, lake, or delta. This formation is the Triassic Poleo Formation, part of the Chinle Group, which is thought to be a dune formation, so the cross bedding formed under the influence of wind. I’d naively say the wind was from the south (right in these photos) but without a more extensive study of the cross bedding, it’s impossible to be sure.

Then on to La Joya de Pedregal:

The flat plain here, La Joya de Pedregal (“the jewel of the stony ground”) is likely not an erosional surface, but a surface underlain by the resistant Poleo Formation. Basalt clasts from the Jemez volcanic field to the south accounts for the “stony ground”; the “jewel” is, I suspect, a conceit.

At left is Cerro Pedernal, which I can no more seem to stop photographing than Georgia O’Keefe could stop painting. It displays an impressive rock column we’ll look at in a moment. At center, almost lost in the haze (which is mostly juniper pollen this time of year), is San Pedro Mountain. At right is Mesa Alta.

A close up of Cerro Pedernal, similar to many I’ve taken before, but now with a decent telephoto and good lighting.

The plain in front of us is capped with Triassic Poleo Formation with scattered hills of Painted Desert Formation. Both were deposited in the valley of the Chinle River, an ancient river that flowed from at least as far east as Texas to what was then the west coast of North America in Nevada. The red cliffs at the base of Cerro Pedernal are Jurassic Entrada Formation, with a white cap of Todilto Formation. Both formed in a desert climate, the Entrada Formation as sand dunes, the Todilto as a brine lake that dried out to form a thick salt pan. Above these are slopes underlain by the Jurassic Summerville and Morrison Formations, the latter forming the colorful cap of the hill to the right. The cliffs above these are formed by the Cretaceous Burro Canyon and Dakota Formations; the slopes above these are poorly preserved beds of the Cretaceous Mancos Formation and the Tertiary Abiquiu Formation. Immediately beneath the cap are Santa Fe Group sediments, then finally the cap of 8-million-year-old lava of the Grulla Plateau.

I continued on through Coyote, featured in the film, Singin’ In the Rain, as one of the tiny isolated towns where Don Lockwood and Cosmo Brown performed vaudeville before making it in Hollywood. (I recall the first time I saw the movie, as a freshman at BYU, where I shouted out “It exists! I’ve been there!” which was not actually terribly well received.) It’s actually a beautiful area, if you like red rock desert. Beyond the town, I was on ground I haven’t traveled in at least forty years. The last time I was here, our family was coming back from a winter trip to Idaho, it was snowing, my father had come through Farmington to avoid the Colorado mountains, and he decided to go around the Jemez via Coyote. Plus, I think he was not adverse to just a little wanderlust.

An example of folded rock beds just past the town.

To the right is Mesa Naranja (“Orange Mesa”). Just right of center, the beds of rock underlying the mesa begin to plunge downwards — an example of folding. On geological time scales, sedimentary beds are ductile, slowing deforming to accommodate tectonic movement in the deeper rocks beneath. The canyon left of center marks a fault where the beds have actually fractured.

Some Permian Cutler Group beds, just because.

The map identifies this as the El Cobre Canyon formation within the Cutler Group. This is an early Permian formation that has yielded some important land vertebrate fossils from before the time of the dinosaurs.

The red beds are Arroyo del Agua Formation of the Cutler Group. There are thin beds of Shinarump and Salitral Formation towards the top of the mesa, then the resistant cap of Poleo Formation; the last three formations are all part of the Triassic Chinle Group.

A little further on came a good spot for a panorama of Mesa Alta. Here I was glad for a tripod to take a zoomed panorama.

The ground in front of the mesa is a cover of young sediments over Poleo Formation. The lower cliffs are Jurassic Entrada Formation capped with Todilto Formation; then slopes of soft Summerville Formation, and more resistant cliffs of Morrison Formation. The mesa is capped with Cretaceous Burro Canyon Formation with occasional high points of Dakota Formation.

I’ve been looking mostly to the north, where the view is spectacular. To the south are gently forested slopes leading up towards San Pedro Peak, a very gently sloping mountain. I finally got to a spot where I could get a clear shot over my shoulder.

Not a great shot; the weather was deteriorating. By the time I had a better view angle, the mountains were completely socked in with snow.

This mesa has a thick cap of Todilto Formation, rich in white gypsum nodules, over Entrada Formation.

The road then passed through a very interesting road cut.

This is part of a hogback ridge underlain by Cretaceous Mesaverde Group beds. Most of the rock here is from the Menefee Formation, with just a thin cover of the younger Cliff House Sandstone at left. The upper and lower parts of the Menefee Formation are coal-bearing; here, the beds are not rich enough in carbon to be worth mining, but in other locations in the San Juan Basin, great quantities of coal are mined to power the Four Corners power plant.

This is also an example of a regression sequence. Further east, older beds of Mancos Shale indicate the area was under a shallow ocean. The Lookout Point Sandstone — missing here, perhaps from faulting — marks the sea retreating and leaving behind beach sand. Behind the beach was a coastal swamp, in which rotting vegetation accumulated to form coal. Then came continental deposits of sand, forming the middle of the Menefee. The process then reversed, leaving another beach deposit (the Cliff House Sandstone) and then marine shale beds of the Lewis Formation.

These rock were cool enough to me to take some samples.

Middle Menefee Formation:

Notice the bits of fossilized wood in the sample.

Upper Menefee formation:

This is some not-quite-coal, rich in carbon but with too much clay admixture to be useful. I imagine a piece of it would burn, though. Hmm. (Runs off for a few minutes.) Nope, does not ignite, or at least not easily.

Cliff House Formation:

Moderately well sorted, with angular grains and many lithic fragments. Not a particularly mature sandstone.

About this point I was startled by some loud squawking and thrashing in the river behind me. I turned to see two beautiful mallard ducks, or, to be precise, mallard drakes, in flight, one chasing the other — which had apparently been trying to make a move on a couple of nubile female mallard ducks the first drake had already claimed. I didn’t get my camera in action in time for the drakes, but I got some shots of the ducks.

Okay, don’t make fun of me; I’m not really a bird watcher. “Duck” I’m reasonably clear on; “mallard drake” I’m pretty clear on, too, since their appearance is so distinctive. (They have vivid green heads during the breeding season.) Everything else I have to Google. The first swimming duck, when zoomed in on, looks like a northern pintail drake. The second could be a female of almost any species of duck, including both mallard and pintail. My guess is that the pair in the water are a breeding pair of pintails (it’s the right time of year), and who knows what the two mallard drakes were fighting over. It’s apparently past the main breeding season for mallards, but the drakes are still capable of breeding even this late, and apparently they’re willing to mate with almost anything as they get close to the end of the breeding season.

Regardless, I watched the two mallard drakes circle around squawking furiously at each other for several minutes. Then I got back to the rocks.

I tried putting my keys on the outcrop to provide scale. Slid off. Tried again. Slid off. Tried a different spot. Slid off. Shale is slick. I finally muttered a few naughty words and shoved one of the keys into the outcrop to act as a piton.

Notice how distinct the contact of the Menefee Formation, at right, with the Cliff House Formation, at left, is.

Just down the road is an exposure of Lewis Shale.

Like most marine shale, this stuff disintegrates back into mud at the least excuse.

Another over the shoulder shot of a hogback ridge of Ojo Alamo Formation.

There is some controversy about this formation, which has proven difficult to precisely date. It’s normally regarded as the lowest Paleocene formation in this area. But some of the lowest beds are reported to have dinosaur fossils, which would then be post-Cretaceous dinosaurs, unless the lowest part of the formation is actually Cretaceous in age. Then again, the famous chalky layer produced by the asteroid impact at the K-T boundary is not present anywhere in the San Juan basin, suggesting there’s a discontinuity that has erased the exact boundary.

I’ll let the real geologists sort that one out.

There was a convenient spot here to eat a late lunch. The weather was also failing fast. There was already snow falling in the higher peaks; I would not get my San Pedro Mountains shots today. I did get a nice shot of the continental divide to the west.

No, seriously. The Continental Divide runs along the crest of these hills. On this side, precipitation eventually runs into the Rio Puerco, which feeds the Rio Grande. On the far side, precipitation fetches up in the San Juan River and eventually joins the Colorado River. The hills themselves are underlain by Eocene San Jose Formation, which is in the ballpark of 40 million years old. It’s the youngest rock we’ve seen all day.

This outcrop was too gorgeous to miss.

Also San Jose Formation. I guess I can say that I now know the way to San Jose. I don’t know that it gave me peace of mind, precisely, but I was having a pretty good day, notwithstanding the miserable weather.

Some San Jose Formation in a road cut.

Not terribly well consolidated, readily weathering back into sand. I got a sample anyway.

A moderately coarse, poorly sorted, dirty sandstone. Not very mature.

I thought this next might be my Ansel Adams moment of the day.

The hills in this panorama are remnants of a rather extensive pediment surface found throughout the area north of Cuba. However, this really wasn’t the day for it.

Another gorgeous road cut exposure.

More San Jose Formation, this exposure being heavily cross-bedded and more strongly indurated (cemented as rock.) A sample:

Coarser and more heavily cemented than the earlier sample.

Just north of Cuba, I came to a road cut exposing the Nacimiento Formation.

At left a local fault brings the overlying San Jose Formation into contact with the Nacimiento Formation. The Nacimiento Formation is a Paleocene formation, 64 to 61 billion years old, formed from sediments eroded off the Sierra Nacimiento to the east.

South of Cuba, I had a good view of Mesa Portales to the northwest.

The mesa is underlain by Cretaceous Pictured Cliffs, Fruitland, and Kirtland Formations with a cap of Paleogene Ojo Alamo Formation. There’s plenty of fossils, including petrified wood, in these beds, and lots of arguments about their exact assignment.

A little further on was La Ventana North Mesa:

This is underlain by Menefee Formation and capped with the La Ventana Member of the Cliff House Formation.

What I thought would really be my Ansel Adams moment of the day: A view into the Cabezon Peak area with enough mist to really bring out the many volcanic plugs. “Valley of the Giants.”

And maybe this would have been my prize picture of the day, except that the next is even better:

The geology is Todilto Formation capping Entrada Sandstone with lowermost slopes of Chinle Group. The art is what stands out with this one, though. The only thing marring it is the oncoming car; even that might have improved the picture, by humanizing it, if it was just a little better placed.

Look, maybe there are photographers who can plan these kinds of shots and make them work. But I suspect most really terrific photographs come from taking lots and lots of photographs of anything that hits you as hey, this could be a great shot and having a very few turn out really well. And I wonder how that works nowadays when taking bazillions of photos is no longer hideously expensive. Actually, I think I know how that works: Schlubs like me with a halfway decent tourist camera are turning out photographs regularly that the best photographers of fifty years would have given their eyeteeth to have taken.

(I know at least one professional photographer has looked at my blog. Go ahead and flame me; I probably deserve it.)

I had a decision to make. I had originally planned to circle clear through Bernalillo and Santa Fe, so as to completely circumnavigate the Jemez. But I was getting tired and the weather was lousy. Cut through the Jemez at San Ysidro? Of course, lousy weather was going to be even lousier in the high elevations. I decided to do it anyway.

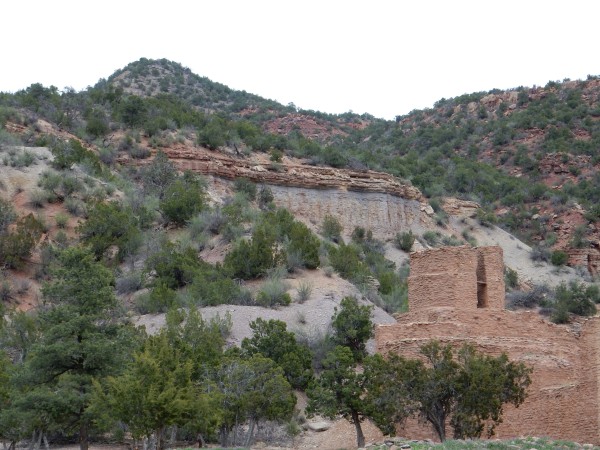

And stopped, on impulse, at the Jemez Springs historical site.

… at least in part because the cliffs behind the ruins had caught my eye.

I know: I am such a geek. My older sister has always found this endearing; it probably irritates most other people.

The geologic map for this area shows Pennsylvanian Madera Group limestone overlain by Permian Abo Formation. In most places this is a gradational contact, with Madera Group-type rocks slowly giving way to Abo Formation-type rocks as you ascend; there is no sharp contact. But this sure looks like Abo Group sandstone in sharp contact with underlying limestone breccia. I’ll have to take a closer look when I have more time. The map shows a small outcrop of terrace gravels right around here; perhaps that’s what this is.

From there to home. It was snowing so heavily in the caldera that one could barely see the caldera floor. Once past the caldera, I did stop for a shot of the San Miguel Mountains, thinking the lighting was good, but the picture didn’t come out like I had hoped.

I’ll doubtless have another chance.

At home, there were birthday presents: Sugar-free brownies, an Oxford Annotated Bible, three geology textbooks, and Huston’s The Battle of San Pietro; my tastes are pretty eclectic. Not a bad way to spend a birthday.

Really good, as usual. Minor note: nowadays it’s usually argon-argon dating. But I suspect the result is still called potassium-argon dating.

I suspect argon-argon dating as well. The date on the El Rito beds was back in 1985, so it’s possible it actually was K-Ar dating.