Great American Eclipse wanderlust, day 14

Days 12 and 13 may be found here.

I awake, eat the usual camp breakfast, and clean up. On the way back from dumping my trash in the dumpster boxes, I get a glimpse of some geology through the trees.

Capitol Dome, at least according to Bing Aerial View.

My campsite (with my tent already down and packed.)

I drive to the visitors’ center. There is a hike with a ranger scheduled along one of the canyons at 9:00. It is now 8:30. I decide I have just enough time to go look at the Goosenecks.

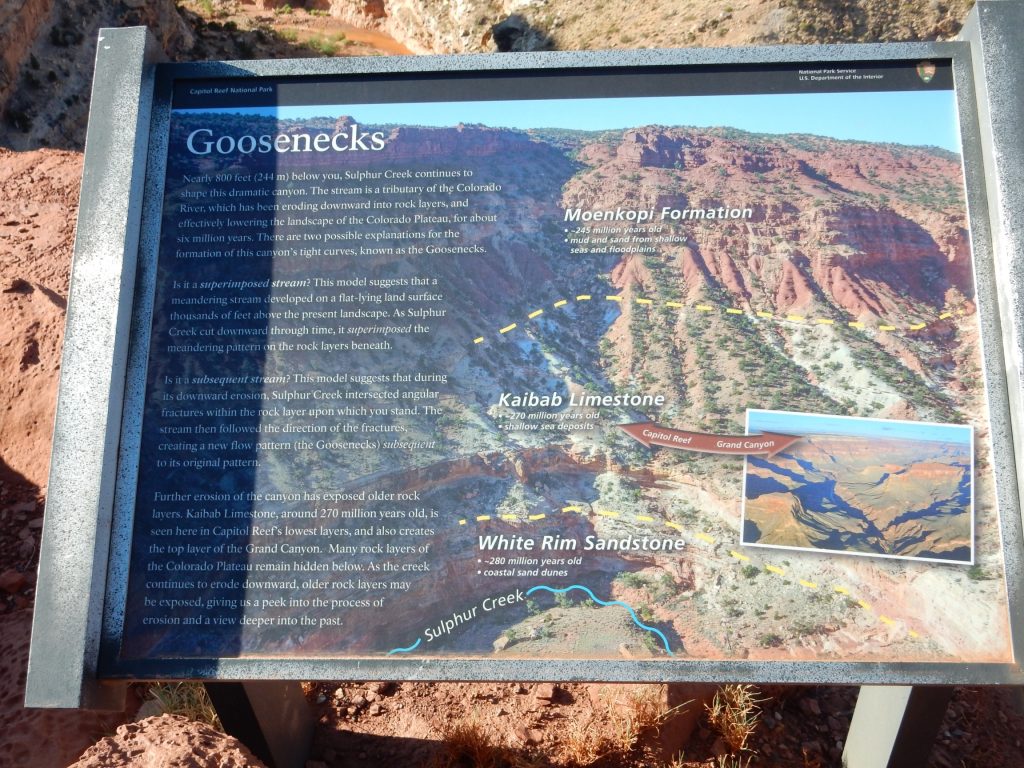

Here in the canyon of Sulphur Creek are the oldest beds exposed in the park. Hey, don’t take my word for it:

All the formations I’ve seen so far at Capitol Reefs have been Mesozoic in age (Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous.) Here we get back into the Paleozoic; both formations deep in the canyon, the Kaibab Limestone and White Rim Limestone, are Permian in age.

The boundary between the last period of the Paleozoic (the Permian) and the first period of the Mesozoic (the Triassic) was the time of the worst extinction event in Earth’s history, when most of the families of life present in the fossil records from before the extinction disappear forever. There’s all kinds of speculation to the cause; one good candidate is the eruption of the Siberian Traps, a huge basalt field, which may have severely disturbed Earth’s climate. Another candidate is a giant meteor impact in an ocean basin, where all traces of the impact structure would long ago have been destroyed. (Continental crust can be ancient, up to 4 billion years old; oceanic crust is all young, less than 250 million years old, because this heavier crust is constantly recycled into the mantle.)

I hurry back to the headquarters in time for the nature hike. To my amusement, most of the first visitors to show up are older men like myself, some clearly traveling by themselves. I’m actually one of the younger ones. But some young couples also join us by and by.

The ranger is a Ph.D. candidate in botany, specializing in conservation genetics. This means he studies the genetic diversity of threatened and endangered species. He’s been working in the park during the summer and his knowledge of the botany is impressive. I know just a little botany myself, so this is a fairly educational hike.

We start along the Fremont River and the ranger points out various species of salt bush and willow. And beaver damage:

The picture isn’t focused very well, but you can see the chew mark from the beavers. The ranger informs us that, in this area, they tend to live on the river banks rather than damming rivers and building lodges. Flash floods, you see.

Ripple marks in Moenkopi beds, cool:

Somewhere along here we came to an underhang of a cliff, with a mess of pine needles and dark exudate smeared under the cliff.

Young Kent: “Oil seep!”

Wise Kent: “Not likely. Probably a rad midden. You seem to have petroleum geology on the brain.”

The ranger agreed with Wise Kent that this was probably a rat midden. Pack rats live in them, cement the debris together with their own urine, and the nests sometimes remain in use for decades or centuries. I boldly sniffed at the rock; no petroleum smell. No smell at all, in fact, which kind of surprised me; I would have expected a strong urine smell. And I forgot to take a picture.

I also fail to bring home a picture of the terrace gravels north of the river, which stand out in the satellite photo and on the ground. Which is strange, because I distinctly remember pulling over while driving past it the previous day to photograph some of the many basalt boulders in the terrace. Dunno what happened. The terrace marks an older, much higher stand of the Fremont River, full of glacial debris that includes basalt boulders from volcanoes to the west.

Somewhere along the trail, as the crowd gathers around a small bush that the ranger is enthusiastically describing for us, I try moving around a young couple to get a better look. I lose my footing on the loose gravel at the edge of the trail, not badly, but there is a steep cliff there. Rather to my astonishment, the woman bodily grabs me by the backpack, picks me up bodily, and set me in the middle of the trail. I am impressed, and deeply grateful for the concern, even if I don’t think I was actually in that much danger of going off the cliff.

We reach a nice lookout point, and more ripple marks.

The ranger ends the hike here, but invites anyone interested to continue on to the Fremont Overlook. I find myself hiking with an Australian fellow named Paul. He describes himself as a “man of leisure” (retired) visiting the States with his wife, a university professor attending a conference in San Diego. He had apparently decided to go see some back country while she attended the conference.

I repeat a joke I’d recently read: An Englishman arrives in Australia and is passing through customs. The customs official asks if he has any felony convictions. “Er… I didn’t know that was still required.” Paul thinks this is hilarious. (I’ve yet to meet an Australian that did not have a good sense of humor.)

Raindrop impressions and desiccation cracks?

Lizard:

We are hiking along an unnamed tributary canyon of the Fremont River, incised deeply into the Moenkopi Formation.

At the overlook at the end of the trail:

The panorama shows the large terrace deposit just left of center, north of the campground area. So I guess I have a photograph of it after all.

It’s time to head home.

With pauses for interesting geology, of course. Here we see Kayenta Formation on top of Wingate Formation.

Both are Jurassic formations. The Wingate Formation is the massive beds forming the lower half of the cliff, while the Kayenta Formation is the thinner beds forming the upper half of the cliffs.

In the background is a dome of Navajo Sandstone.

As I head back east out of the monument, I’ll retrace yesterday’s beds in reverse order, of course. Older beds to younger beds. I plan to photograph some I missed yesterday, now that I’m a little more familiar with the area.

Kayenta Formation sandwiched between Wingate Formation and Navajo Formation.

More Navajo Formation.

The feature right of center has no name I could find on a map, which I suppose is better than having a cringe-inducing name.

Further east, Horse Mesa is capped with the next youngest formation, the Carmel Formation.

This forms the thin beds atop the mesa, lying above slopes of Navajo Formation.

A closer look:

A little further on is one of the formations I missed coming in: the Entrada Sandstone.

The Entrada Sandstone forms the low cliffs in the foreground. Behind are cliffs of the Cutler Formation (the whitish beds at bottom), the Summerville Formation (the reddish slopes) and a cap of Morrison Formation Salt Wash Member. All are Jurassic in age.

More Entrada Formation.

The Entrada Formation is massive sandstone further east, in the Moab area and back home. Here there’s a fair amount of silt and clay. This reflects the fact that the source of sediments for the formation was the ancestral Uncompahgre Uplift, which stretched from near the Utah-Colorado line to roughly the location of Espanola. Closer to the uplift, the sediments were coarser (sand) and here, further away, they’re more fine (silt and clay).

Back to the Summerville Formation:

Beyond are colorful beds of the Morrison Formation.

Brushy Basin Member, Morrison Formation

Tununk Shale Member, Mancos Formation:

This should have been an Ansel Adams moment, but once again I accidentally bumped the mode switch on my camera to “soft-focus bridal.”

I love the contrast here between the green fields, irrigated from the Fremont River, and the harsh slopes of South Caineville Mesa beyond.

A cap of Emery Sandstone Member, Mancos Formation, over slopes of Blue Gate Shale Member, Mancos Formation.

Further down, I’m off the detailed geologic map, but I believe this is also Emery Sandstone over Blue Gate Shale.

Likewise Factory Butte:

I pull into Hanksville, refuel and dump waste, and proceed towards Hite.

The Henry Mountains loom ahead, and I stop for a panorama.

My geologic map for this area is very large scale (therefore not at all detailed) but this sure looks like Entrada Sandstone in the immediate area.

A little further on, and a good place for a deep panorama of the Henry Mountains.

The Henry Mountains, like the La Sal Mountains and Abajo Mountains seen earlier in this trip, are Tertiary laccoliths. They formed around 25 million years ago when magma penetrated the upper crust and pushed up the overlying sedimentary beds, almost like a blister. The magma cooled and solidified to form domes that are now exposed by erosion.

The nearby bluffs are capped with Morrison Formation.

The eastern dome of the Henry Mountains is Bull Mountain.

I feel myself itching to climb it. But not this trip.

And maybe I don’t need to! I find myself in a road cut full of gravel, clearly eroded off the mountains. Here I find chunks of the mountain without having to climb the mountain.

A really pretty diorite, an inrusive rock composed mostly of plagioclase feldspar. Some samples have truly spectacular hornblende crystals.

The source:

The very flat ground between here and the mountain is likely another pediment surface.

The road begins to descend towards the Colorado River.

The massive cliffs are Wingate Sandstone, topped by thin beds of Kayenta Formation. In the distance, some domes of Navajo Formation rest on top of the Kayenta Formation.

The Chinle and Moenkopi Formations begin to show at the base of the cliffs.

The white beds across the river, which could easily be mistaken for Navajo Sandstone, are Permian Cedar Mesa Formation. Above this are reddish beds of the Organ Rock Formation, then another white bed of the White Rim Sandstone. The mesa tops are Moenkopi Formation.

Hite was the only crossing of the Colorado River between Moab and Lees Ferry until the Glen Canyon Dam was completed; it remains the only crossing between Moab and Glenn Canyon Dam. The town experienced a brief boom during the uranium rush, but the town site is now drowned by Lake Powell, the reservoir behind Glenn Canyon Dam.

I ascend from the Colorado, and will be in Moenkopi country for some time. It is already after noon and I am starting to feel a little rushed to get home.

My geologic map is not good for this area, but I suspect this is weathered out of Wingate Formation.

Moenkopi Formation.

I stop briefly at Natural Bridges National Monument, mostly to eat lunch and dump waste, then hurry on towards Blanding. As I hit the summit of the road south of the Abajo Mountains, the storm breaks; small hail pours down and it’s actually a touch scary for a few minutes. But I pass through the storm and continue on my way.

I’m back in well-traveled ground. But I do spot one feature south of Bluff that I’ve not noticed before, because I’ve only driven the road south to north before; this is my first time to drive it north to south.

This is Boundary Butte. Alas, it’s too small to appear on my geologic map, but it’s clearly a volcanic dike.

I arrive at Shiprock in the late afternoon; something is going on. Police cars have blocked part of the main intersection, but I’m waved through. I never do find out what it was about.

There follows a long, slow drive to Cuba, then around the Sierra Nacimiento via Jemez Springs. It is well after dark when I get to Jemez Springs, and it is clear there has been very heavy rain. My car gets sloshed with mud passing through one half-drowned intersection.

And home.

Pingback: Great American Eclipse wanderlust, days 12 and 13 | Wanderlusting the Jemez