Kent And Bruce Have Yet Another Excellent Adventure, Day 3

Day 2 may be found here.

After an excellent night’s sleep, I awake and start making myself breakfast: steel-cut oats, chocolate pancakes, bacon and eggs, buttermilk. The oats have ground flax added and the pancake mix is a whole-grain, protein-fortified mix to which I add inulin. This seems to make it easier on my pancreas. I’m borrowing Lori’s frying pan but I figure sparing her the cooking makes up for it.

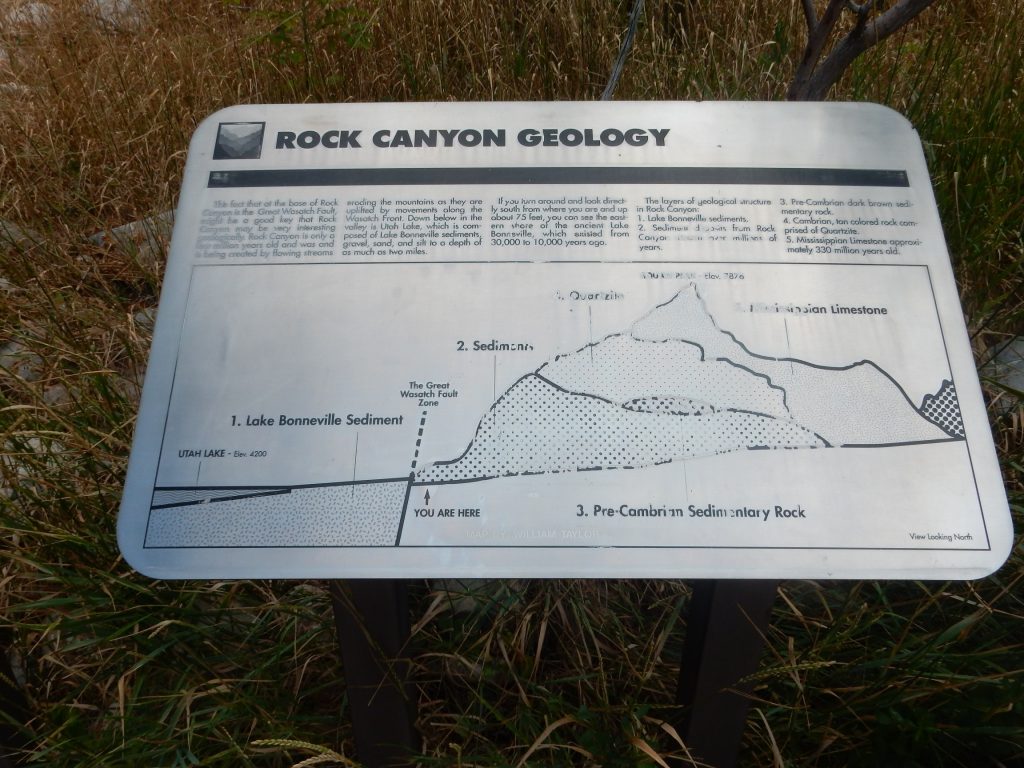

The family reunion won’t really get going until this evening, so I decide to explore Rock Canyon, located east of Provo in the Wasatch Front.

That’s a bit vague. But it’s a good start, and I’ll fill in the details later with my geologic map.

I grease up with sunscreen and bug repellent, activate my Spot-3, grab my stick and pack with water bottles, and head out. The high canyon walls are going to make it hard to get good GPS locks.

The lower slopes are geologically young colluvium eroded from the canyon. The dark lens at center is apparently the top of the lowermost bedrock formation here, elsewhere covered by the young colluvium. It is identified as Neoproterozoic Mineral Fork Tillite. This contains fossils of a microscopic alga, Bavlinella faveolata, which suggest an age between 650 and 750 million years. This would put this in the Cryogenian Period of the Neoproterozoic Era, a time when Earth is thought to have experienced the worst ice age in geologic history, the Sturtian glaciation. At this time, the Utah area was located not far north of the equator; this and the fact that Bavlinella faveolata is a planktonic alga shows that glacial till was being deposited offshore even at low latitude.

Above the lens of Mineral Fork Tillite is a great thickness of Cambrian Tintic Quartzite, around 520 million years old. This was deposited as sandstone that was later subject to enough head and pressure to partially recrystallize it. The peak on the skyline is Squaw Mountain, underlain by the Mississippian Humbug Formation, around 340 million years old.

I see an outcropping across the arroyo.

But I pause to admire the lower canyon

I find a way across the arroyo. There is a trail towards the outcropping.

The tillite looks like a slate here.

Further up canyon, there are good exposures around a water tank, whose access trail gives good accessibility.

The tillite is mostly slaty matrix, but with definite small clasts (fragments of rock) embedded in it. These have the angular shape characteristic of glacial till. A chunk of rock at the bottom of a glacier tends to be ground flat on one side as the glacier drags it along the glacier channel; then it hits an irregularity in the channel, flips, and gets ground flat on a different face.

None of the clasts show signs of deformation; this is not unusual when crystalline clasts in a mudstone matrix undergo metamorphism. The clasts are strong enough that the metamorphic deformation is taken up entirely by the softer mudstone.

Looking up, I see that not all the clasts are small.

I look at the contact of the tillite with the overly Tintic Quartzite.

Something seems slightly off here. For example, in the alcove at right, it looks like the tillite has “intruded” the quartzite. That’s not really possible, is it? Incipient sedimentary dike, perhaps?

I consider climbing up to the contact, but the slope is steep and covered with scree, and I’ve developed a bit of an allergy to steep, scree-covered slopes since last autumn. However, I go over to where the overlying Tintic Quartzite reaches the canyon floor.

The quartzite is light gray on a fresh surface, but weather to rusty red, presumably as reduced iron in the fresh quartzite is oxidized.

The quartzite is distinctly bedded.

And the beds are often fantastically contorted.

This puzzles me a little. The beds of tillite beneath seemed to be more or less horizontal.

More contorted quartzite.

The upper canyon walls, above the quartzite, are harder to identify, particularly since I don’t know this area well.

However, the layering here again appears horizontal. To be sure, in deformed rock, layering and bedding are two different things; the original layers may still be distinguishable from composition even when deformation has caused the rock to be jointed in a different direction. The white band may be Mississippian Fitchville Formation, but I can’t be at all sure.

However, the geologic map makes it fairly clear I’m now entering an area underlain by Ophir Formation. This is a Cambrian shale formation that seems to be less resistant. so that I’m entering a slightly more level part of the trail.

Here I enter the Maxfield Formation, a Cambrian limestone formation resistant enough to form cliffs again.

Here I cross the Fitchville Formation.

The bed appears to have been folded right over. This may be illusory; the bedding and the layering are so different in this canyon that it can be confusing, especially to someone new here.

I come across some rock climbers.*

They are scaling a cliff in the next formation, the Mississippian Gardison Formation. It’s impressive on the north side of the canyon as well.

It seems obvious these beds have been seriously folded.

Yet geologic mapping shows the formations lying relatively flat.

Here I find an outcropping in the canyon floor.

Assuming this is actually bedrock, it’s the Mississippian Deseret Limestone. It’s suppose to have some fossils, but I find none here. In fact, I pretty much struck out all day, which was disappointing; I hoped to see some trilobites in Cambrian beds, which do not exist in northern New Mexico.

The background rocks, assuming they’re not landslide boulders, are Mississippian Great Blue Limestone. However, I’m now hiking a heavily forested trail that barely lets me see the canyon walls. I hope to hit a jeep trail further up the canyon where the view may open out a little. The trail eventually runs back to Squaw Mountain, but I don’t have time for that.

I pause here for my lunch and a fresh coating of DEET.

A glimpse through the trees of … I don’t know what without context. To the northeast.

Possibly the southern end of Cascade Mountain. If so, we’re looking at Pennsylvanian Oquirrh Formation, a very prominent and thick formation that unerlies most of the upper Wasatch Front.

I decide to turn back at about this point. I’m feeling fatigued and my feet are sore, and after all, I’m a 56-year-old diabetic hiking on his own in the mountains…

I’d actually made it about four-fifths of the way from the mouth of the canyon to the campground and dirt road.

On the way back, I climb above the trail to get a clear shot of the canyon wall to the south.

I’m looking for a contact where the contorted lower beds become level. There isn’t one. It’s the bedding versus layering thing again. The formations are still lying more or less flat as they were deposited; but weak metamorphosis (it wouldn’t be strong or there’d be no reports of fossils in these beds) has changed the jointing in the rock, the “bedding”, to be oriented differently from the layering and almost at random. I’m going to have to get a metamorphic geologist to explain this to me at some point.

The rock climbers are still at it.

Another shot of Squaw Peak.

Underlain by Humbug Formation, though I can’t judge where the contact with the older formations is. I’m still inclined to think the white layer is the Fletchville Formation.

The canyon mouth beckons.

That’s Tintic Quartzite, again, to either side.

There’s a gate, but no Sweeney. Nor nightingales, for that matter.

I come back in view of that contact between the Mineral Fork Tillite and the Tintic Quartzite. It still looks “off” to me.

That looks so very much like an intrusion, and while the rock is similar to the Mineral Fork Tillite, it has a slight greenish cast to it that seems different. I wonder if this is a local intrusion that happens to resemble the tillite. I consider; It’s a long climb and I’m fatigued. You are more likely to hurt yourself when you’re tired. I refrain.

Only after I get home will I read that geologists report a diabase sill at the base of the Tintic Quartzite in this area. Well, that leaves me next time to take a good look.

I pass the Provo Temple on the way out. Seems fitting to view the Mountain of the Lord’s House after seeing mountains.

I’ve heard people pooh-pooh human architecture in comparison with the grandeur of nature. I don’t see it as an either/or proposition.

On a whim, I head north, thinking to drive the Squaw Mountain road, which I have not done since I was a BYU undergraduate (mumble mumble) years ago. I spot a definite, for-real fold in the rock beds of Cascade Mountain.

May be associated with the Big Baldy Thrust Fault.

I pull over for a panorama at a hairpin turn.

At left is Orem, with Utah Lake behind and the easternmost range of the Basin and Range Province, Lake Mountain, behind that. The Wasatch Front is part of the high spine of Utah, which separates the Colorado Plateau to the east from the Basin and Range to the west.

At center foreground are low hills that look like they should be an alluvial fan or a glacial or lake deposit; but they’re underlain by pristine Mississippian beds of the Great Blue and Manning Canyon Formation. Beyond, just left of center, is Big Baldy, underlain by Oquirhh Formation, as is the great bulk of Mount Timpanogos to its right. Further right is Provo Canyon and Cascade Mountain.

I believe the prominent beds halfway up Cascade Mountain seen from here that lack vegetation are the Bridal Veil Limestone Member of the Oquirrh Formation.

I reach the overlook and take one more panorama.

And one final geology shot on the way back.

Provo Canyon. The U-shape of this valley is typical of glacier-carved valleys, indicating that this area was glaciated during the last Ice Age. Timpanogos itself is described in one source as a glacial horn, and there are certainly two prominent cirques, bowl-shaped depressions carved by glacier heads, on its northeast flank. The southwest flank is less obvious, but it does look in the satellite view like a small cirque.

I get back to Lori’s and join Susan, my mother, and Lori’s husband, Robert, and Susan’s husband, Lowell, for dinner at Olive Garden (Mom’s favorite.)

That’s Robert and Lori at left and Lowell, Susan, and Mom at right. I managed to find something not too dangerous looking on the menu — a carbonara dish, without too many noodles, as I recall — that was delicious.

I find it remarkable that my mother, who is nearly blind, realized that I was taking a picture.

And, of course, there’s dessert.

Except for me, alas. There was nothing on the dessert menu that I could pretend was diabetic-safe.

And back to Lori’s for the night.

Next: The Archean, and more stuff I can’t safely eat.

* Who granted permission for me to take these photograph.

Pingback: Kent and Bruce Have Yet Another Excellent Adventure, Day 2 | Wanderlusting the Jemez

Pingback: Kent and Bruce Have Yet Another Excellent Adventure, Day 4 | Wanderlusting the Jemez