Kent and Bruce Have Yet Another Excellent Adventure, Days 12 and 13

Day 11 may be found here.

Up at the break of dawn.

Bruce texts that he is on his way. It’s a long enough drive from South Fork that I decide to hike down and check out Point of Rocks in the background.

There have been at least three bridges constructed across the Rio Grande here.

I find this vaguely disquieting.

Point of Rocks appears to be composed of Snowshoe Mountain Tuff, contrary to the road log but in agreement with the latest geologic map. More precisely, the map describes the rock as massive shattered breccia.

There are clasts of solid rhyolite here.

The rain starts.

I clamber up the slope, being careful of my ankle, and about this time I see Bruce’s car pulling into the campground. I text him to look for me waving wildly from the rock; wave wildly; and then hurry back to meet him.

Since my tire is not looking good, we take Bruce’s car. Bruce had found a guide to the mines north of Creede, and we would explore the area further.

The country is beautiful, but there has been extensive damage from bark beetles.

We reach the furthest mine on the road, the Equity Mine, which is also the mine most likely to be reopened when metal prices are right.

The shaft goes surprisingly deep here — better than 1600′, if I recall correctly. The mountain to the east shows some interesting rock beds I’ve not seen elsewhere in the San Juans.

This is apparently part of the margin of the Nelson Mountain caldera, which was identified in the latest mapping effort and is not mentioned in my road log. However, it’s apparently part of the San Luis caldera complex, as is the Rat Creek caldera that emplaced tuffs against the rim here. The reddish rock is a remnant of a volcanic vent of the Rat Creek eruption.

We divert to the Last Chance Mine.

This mine is now owned by a retired photographer who bought it at a bargain from a descendant of the original owners who was willing to be rid of the place. He’s turned it into a fairly decent museum and tourist trap. There are lots of rocks and minerals for sale, and you can pay by the pound to go out on the tailings and collect your own.

Bruce quietly tells me that some of the more spectacular fossils for sale are counterfeit. It seems to be something of an industry in Morocco. However, there are enough real trilobites and ammonites in Morocco that you can buy a Moroccan trilobite or ammonite at a rock shop and be moderately confident they’re authentic. I buy a couple for friends and family.

We skip the mine tour and I sign up to go glean in the tailings. I hope to find pyrite, but instead I find sow’s belly chalcedony.

Partially buried and covered with mud, but you can still imagine how beautiful the stone is. I do not take it: It easily weights over 50 pounds, and I was not planning on spending $100 here today. Besides, I don’t have a lapidary saw with which to do it justice. But I get some nice smaller samples.

In addition to sow’s belly chalcedony, there is tourmaline

limonite

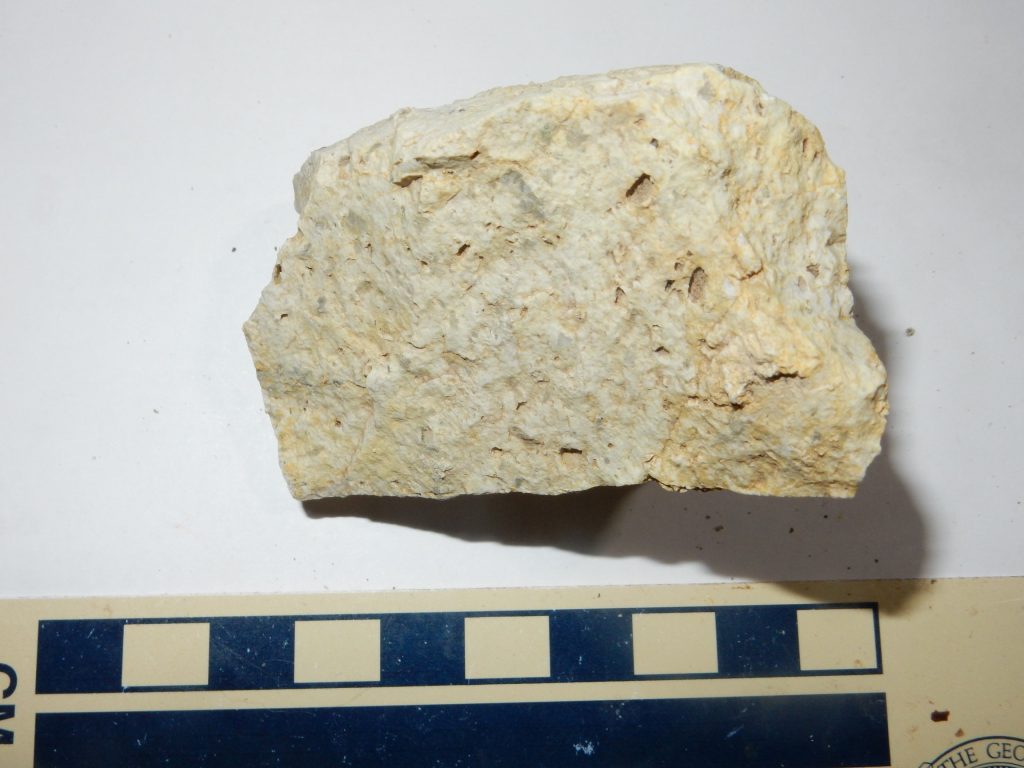

quartz, most likely

and possibly this also.

I return with my prizes to find Bruce chatting with the fellow that owns the place. His home is swarming with rodents.

They are pets. At least, I don’t know how else to describe chipmunks so tame they will climb up into your lap to eat a peanut out of your hand. A small girl sees that Bruce has trail mix, begs for some to feed the rodents, and Bruce’s supply of trail mix becomes slightly depleted. Watching the critters, I observe some attempts at muskrat love, but Susie apparently isn’t interested.

I purchase a sample of actinolite on the way out, just because.

From the color, I’d guess this is tremolite, the magnesium-rich version of actinolite. It is akin to both jade and asbestos. Try not to inhale.

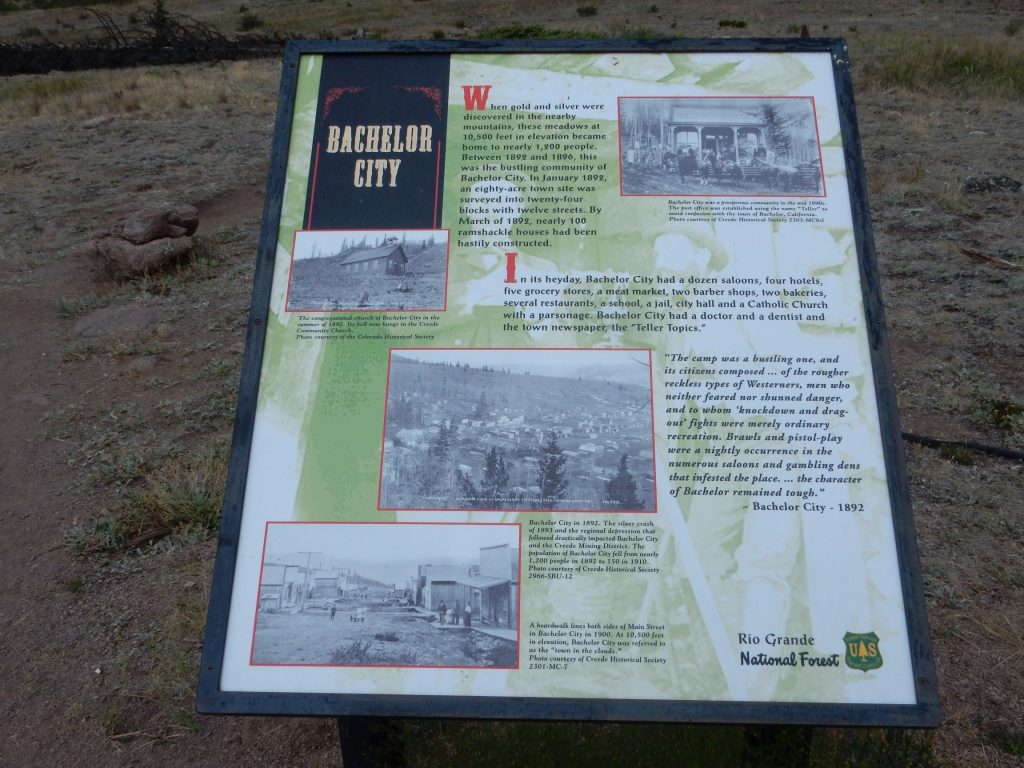

Bachelor town site:

The town has seen better days.

At its peak, Bachelor has a population of 1200. Elevation: 10,500 feet. All that is left are some ill-defined foundations.

The road comes out above Creede. Here

and here.

We drive back into Creede. There is a big rock and gem show taking place in town, most of it in the community center that is tunneled into the solid rock along Willow Creek north of town. I look for andalusite: I have samples of the other two polymorphs of aluminum silicate, sillimanite and kyanite, and would like my collection complete. The only samples are polished, which is not what I want. There is also basalt with peridotite, a rock brought up from the mantle with the magma. I’ve wanted some for some time.

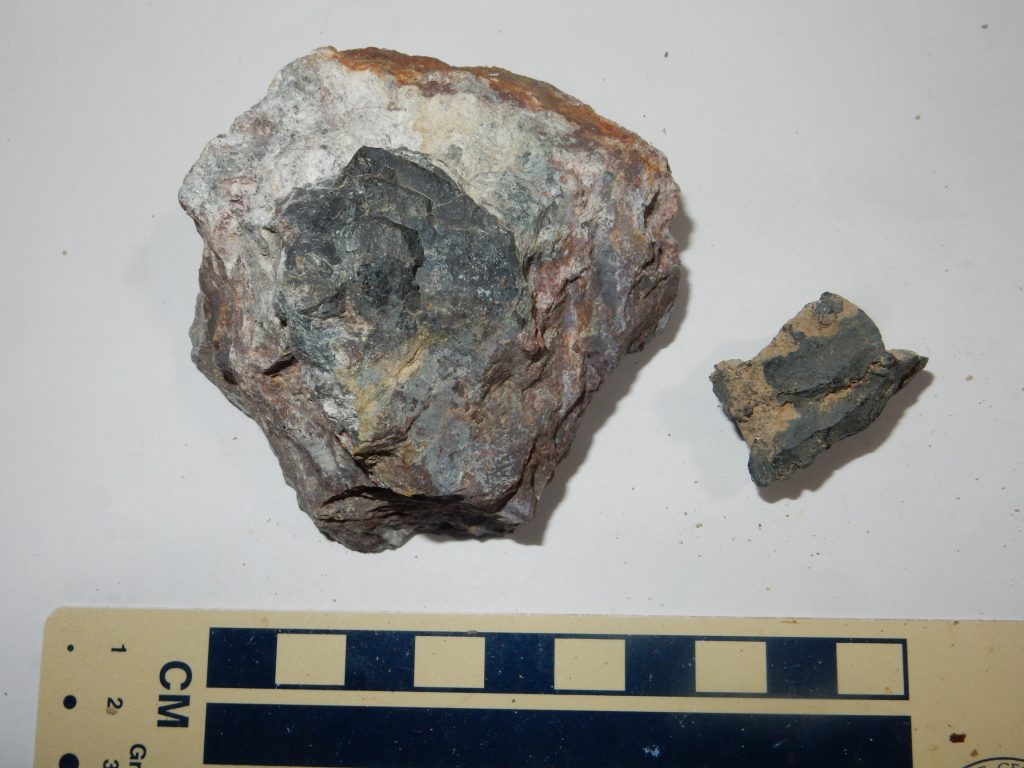

The gray rock is the basalt, a common type of volcanic rock formed from lava that usually originates in the upper mantle. The green patch is the peridotite, mantle rock composed mostly of magnesium silicate, from which the lower-melting components have been removed. The peridotite was brought to the surface as a solid chunk of rock floating in the basalt. This is one for the book.

We emerge from the rock show and find Creede a madhouse.

The rock and mineral show seems to have just about tripled the population of the town. We pick a restaurant for lunch and it takes the better part of two hours. And the food, while okay, is not worth that long a wait, except there’s not much of anywhere else to eat.

At least the weather has finally started to clear when we get out.

We pick up yesterday’s road log where we left off, in the western moat of the Creede caldera.

The ridge at left is part of the margin of the Creede caldera. Both it and the hill to the right are underlain by andesite dating from before the first known caldera eruptions here. They are interpreted as being part of the floor of the La Garita caldera that has been exhumed by eroson.

I actually took this photo to capture the low ridge in the middle distance. This is a moraine, a line of debris left behind by a melting glacier. We don’t have a lot of those in New Mexico (the glaciers never got as far south as the Jemez) so I take a closer look.

The boulders carried by a glacier often have an angular appearance. I ton’d see so much of that here, but looking around a little more:

Next stop show several formations.

The top of the hill is underlain by Carpeter Ridge outflow tuff of the Bachelor caldera, which pooled against the west wall of the older La Garita caldera. The beds underneath that form a small brown shelf are Crystal Lake tuff from the Silverton caldera, erupted around 27.3 to 27.8 million years ago. The lowest shelf is Fisher Canyon Tuff from the La Garita eruption.

We drive up towards Slumgullion Pass. The road log invites us to stop and admire some more geologic features.

We are looking southwest almost directly down the valley of South Clear Creek. The gentle profile suggests this is a glacial valley. To the right is Black Mountain, underlain by outflow Carpenter Ridge Tuff of the Bachelor caldera. The mountain in the far distance is Rio Grande Pyramid.

Elevation 13,827′.

Neither the unzoomed view nor the deep telephoto shot is as beautiful as the slightly zoomed shot.

Looking back down the road:

The mountains on the skyline are close to the Continental Divide; to the north, creeks drain into the Rio Grande and ultimately the Atlantic Ocean while, to the south, creeks drain into the Piedra River and ultimately the Pacific Ocean. These mountains are underlain by the Fisher Dacite, part of a ring fracture dome of the Creede caldera.

Bristol Head viewed from the west:

Bristol Head (the peak at center right) is underlain by a cap of Bristol Peak Andesite. The ledge beneath is Wason Park Tuff, 28.2 million years old, erupted from the South River caldera. The come thick beds of Huerto Formation andesite erupted after the La Garita caldera collapse.

Curiously, the face of Bristol Head facing us marks the southwest wall of the Bachelor caldera — but the caldera was located on the side away from us. Resistant lava ponding against the caldera wall resisted erosion better than the tuff outside, which subsequently eroded away to leave a kind of inverted topography.

The valley we’re looking down is part of the Clear Creek Graben, the south side of which marked the southwest boundary of the La Garita caldera.

A road cut:

If I’m following the road log correctly, this is outflow Sunshine Peak Tuff. The road log describes it as “punky” in texture. Apparently “punk rock” means something different to geologists than everyone else; “spongy” comes close. The road log also says that the rock has chatoyant crystals of saninide; this means they have a particular kind of iridescence. I grabbed a chunk, and the iridescence was indeed beautiful.

It takes a couple of tries, but I manage to capture this in a photograph.

The top of the pass.

We saw a very similar view the previous morning.

A view of the detachment escarpment for the Slumgullion mudflow.

The mudflow occurred about 700 years ago when soil weathered from the Uncompahgre Formation came loose from the top of the mountain and flowed four miles down into the valley below. The pass takes its name from this flow, which reminded early settlers of slumgullion stew. The light area at lower right is apparently not part of the flow, which runs down a valley hidden behind the tree line at center.

It turns out there is a better view point than the top of the pass for the Lake City resurgent dome.

The resurgent dome fills the valley at left center. Assuming I’m reading the map right — this is new territory to me — the peak at farthest left just peeking over the nearer mountains is Sunshine Peak, for which the Sunshine Peak Tuff is named. Front and right of Sunshine Peak is Green Mountain. The peak at the center of the dome is Red Mountain, and the valley to the right of the dome (at center in the panorama, being doused in rain, and with a tree square in the way) is Henson Creek valley. This is an eroded remnant of the northern moat of the Lake City caldera. A resurgent caldera moat is the low ground between the topographic rim of the caldera and the resurgent dome, which is the area at the center of the caldera that is pushed back up by new magma injected into the collapsed magma chamber.

To the right of center, the peak with the broken profile is Crystal Peak (12,935′). Almost hidden in the rain to its left, and capped with cloud, is Uncompahgre Peak (14,316′). We timed this badly with the weather. These peaks are outside the Lake City caldera but within the older and larger Uncompahgre caldera. The older caldera rim is at about the location of the unnamed peak just to the right of Crystal Peak.

Slumgullion Slide, from a precarious perch off the highway.

Slumgullion Slide slid into the valley below and blocked the Lake Fork River to produce Lake San Cristobal, seen from here.

The lake fills part of the erosional remnant of the east moat of the caldera.

Across the lake is the Golden Fleece Mine.

The mine lies just outside the ring fracture of the Lake City caldera, which is located well inside the current topographic moat. This is the result of a combination of resurgence, collapse of the original topographic rim of the caldera, and erosion tending to cut down outside the ring fracture.

View towards Lake City.

The next stop is for what I can only describe as weird history.

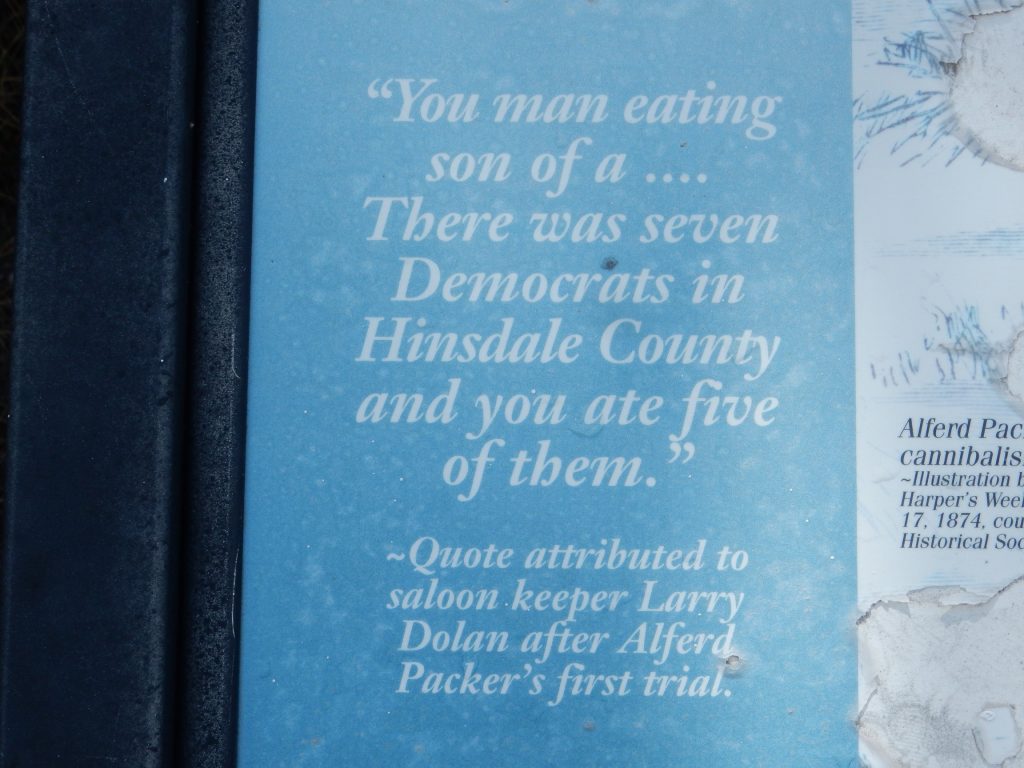

The story is that Alferd Packer was hired to guide these five prospectors into the San Juan. They were caught in severe winter weather in the mountains and only Packer ever came out. He first claimed that the others had abandoned him, but when he was found in possession of some of the personal effects of the others, suspicions were raised. Packer finally confessed to cannibalism but claimed the first victims died naturally before being eaten and the last tried to kill Packer before Packer shot him in self-defense (and ate him.) Packer reneged on an offer to take a posse to the site, changed his story at least twice, and was ultimately sentenced to hang for murder, though this was reduced to 40 years for manslaughter on appeal.

There are various accounts of who said it, but this is the most credible:

The signage here takes it for granted that Packer was guilty of murder. However, recent forensic work has provided some evidence supporting Packer’s final version of events.

We drive into Lake City, locate coffee for Bruce, and head into Henson Creek.

This is Sapinera Mesa Tuff, from the San Juan/Uncompahgre caldera eruption 27.8 to 28.4 million years ago. This actually produced a pair of calderas, but so close together in time that the outflow tuff is indistinguishable. The Lake City caldera erupted later, at around 23.1 million years ago — by far the youngest of the major San Juan calderas.

Looking down canyon:

The ring fault cuts through the right shoulder of this mountain, according to the road log.

Impressive cliffs.

Eureka Member of the Sapinero Mesa Tuff. This was tuff deposited within the Uncompahgre caldera. The road log describes megabreccia along the road and I am thinking it might be in this area. I am out of my reckoning (and it does not help that Bruce’s odometer is busted); we’re not nearly far enough along the canyon for that. In fact, I don’t get my bearings until we spot this.

This is Sugarloaf Rock, a monzonite intrusion from well after the caldera eruption. Okay, the road log says megabreccia after this point. Here?

Probably. The map shows this as Picayune Megabreccia of the Sapinero Mesa Tuff, and I do seem to see boulders embedded in the rock near river level. This would be rock from the Uncompahgre caldera rim that collapsed into the caldera even as the overlying tuff was settling to the surface, so that the two are interbedded.

No question about this being a breccia.

I should take a moment to explain the geology here. We’re in the eroded remnant of the northern moat of the Lake City caldera. The actual ring fracture is some distance to our south. The rivers in the moats have cut down into the rock that was outside the ring fracture, which here is an older caldera floor of the Uncompahgre caldera.

Next stop is at Alpine Gulch. To the south:

The ring fault cuts across the gulch a little over a mile upstream. The ridge on the skyline way up the gulch shows beds dipping south, towards the other side of the resurgent dome. The road log says the gulch coincides with a fault, but none is marked on the geologic map.

In the opposite direction are beds of megabreccia.

The blocks at the base of the cliff are so large that they look like rock beds in place. However, they are most likely large blocks of megabreccia. They show signs of alteration.

The greenish color is typical of low-grade hydrothermal alteration. I’m not sure what the veins are.

We drive on to T-Gulch.

The cliffs at left mark the ring fracture.

The Ute and Ulay veins were located here and were a rich source of lead and silver.

Well, dam:

The plug at left is rhyolite erupted well after the caldera eruption, at around 15-18 million years ago. It sits just inside the ring fracture and likely erupted along the zone of weakness near the ring fracture.

This area sits over a buried monzonite stock that produced a number of base metal veins. Peeking through the trees on the mountain to the south are brightly-colored altered tuffs; the ring fault runs through the trees just above these.

Next stop is Whitmore Falls. There is a trail; Bruce is not up to it but waits patiently while I explore. The trail ends in a lookout point that now has several young trees squarely blocking the view of the falls. Crep. Back up the trail; there are several metastases, some now also blocked by young trees, but I finally find one that has a clear view.

We continue up towards Engineer Pass, which we have no intention of trying to cross; Bruce has heard horror stories. Our road log goes there and beyond but recommends trying it only in a four-wheel-drive vehicle with good ground clearance; Bruce’s car does not qualify. We quit here.

Wood Mountain. The pass is well to the right, far up Schafer Gulch, which has not yet come into view around the shoulder.

There is an old kiln here, once used for firing limestone into Portland cement. The light is too poor for me to get a decent photograph. We speculate on where limestone might have been found in this very volcanic area, but spot an adit and conclude that there must be some local vein of hydrothermal calcite rich enough to support the kiln.

Bruce dares not take his tires further, and I can hardly fault him. We head back, arriving in Lake City in time for dinner. The Cannibal Grill; they do not actually have Democrats on the menu, so I have a patty melt instead.

On the way back to Creede, we encounter young deer in velvet:

Then Bruce drops me off at my campsite and we part ways, until perhaps next spring, when we are tentatively planning to visiting the trilobite beds of the Wheeler Formation near Delta, Utah. Ironically, the beds are just northwest of the old Topaz internment camp for Japanese-Americans during World War II.

I am up the next morning.

The left rear tire is very low, enough that I am gritting my teeth the whole way to Creede. I cannot find an air pump, but I do find a can of Fix-A-Flat at the local gas station; I’ll use it if the tire gets bad enough before I can find an air pump. Fortunately, there is one in South Fork and I pump the tire up there.

I can return home either via Alamosa or Pagosa Springs. The Pagosa Springs route is more rugged, including Wolf Creek Pass, but it’s more scenic, and there ain’t nuttin’ between Alamosa and Espanola. Whereas the Pagosa Springs route at least passes through Chama and Abiquiu. (And now I’m probably going to have to apologize to Tres Piedras and Ojo Caliente.)

The trip is uneventful, though I dare not pause for hiking or photographs. The tire is okay at Pagosa Springs; at Chama, I find the gas pump malfunctioning and drive on in disgust; I’m fine at Abiquiu and at Puye Cliffs. In fact, I get home just fine.

No dog to greet me. (I had to put Laci down a couple of months ago.) But one of the cats sits up straight when she sees me, then comes over for pets. Another cat notices I’m home half an hour later and comes over for pets. Nathan lets his cat out of his room, and she comes over for pets. The other two are, well, cats. Cindy is glad to hear that the tee-shirts were useful. And I have lots to unpack, and lots of rocks to process.

The car: You’ll hear about that next post.