Fallback

It looks like the camera is well and truly unusable. The shutter button normally is pressed in two stages; on the first stage, the camera finds the focus, and when it is pressed the rest of the way down, the actual photograph is taken. Only now, on the first stage, the camera cannot hold the focus; you can see the camera find the focus and then promptly let go of it and lose it. And the cable for downloading the photographs is also no longer working. This all points to a serious problem in the electronics, which I fear is not repairable. But before giving up completely on the camera, I sent an email to a camera repair center that advertises mail-in repair, described my symptoms, and asked if there was any realistic hope of repairing the camera. I got back an email saying they thought it could be repaired, possibly for less than $100, so I’m going to box it up, mail it to them, and see what they can do with it.

I am grieved. I got a lot of satisfaction and a lot of good photographs out of that camera. But life goes on, and so I dug out my old camera, with all its faults but with its remarkable longevity (it’s been in the family for over ten years) and prepared to redo the bad photographs from last weekend.

First, some chores. I headed down to Santa Fe to the auto tire place to have the front tires replaced on the Wandermobile; alas, they turned out not to have them in stock, so I’ll have to drive down again next Saturday to have them installed. Then off to Clara Peak again.

The start of 31 Mile Road.

Notice the dark corners of the photograph. This is vignetting, a common problem with older cameras. (Most recent cameras are pretty good about eliminating it.) It can be compensated for manually using a vignetting processing tool:

The photo still doesn’t have the resolution of the newer camera, but at least I’m back in the business of taking reasonably good pictures of geology.

A panorama of the Tshicoma Highlands and Santa Clara Mountains:

At left is the Sierra de los Valles west of Los Alamos, which becomes the Tschicoma Highlands to the north. Tschicoma Peak itself is just left of center, with a foreground peak appearing slightly higher to its left; Tschicoma is in fact the higher peak, and the highest in the Jemez. To the right are the Santa Clara Mountains, with Clara Peak itself as the high point right of center. At far right is Cerro Roman.

Most of hte road passes through sedimentary beds of the Santa Fe Group and the Puye Formation. I begin photographing outcroppins when the road begins to climb into the Santa Clara mountains and the first basalt appears in the road cuts.

This is an area of landslide deposits containing a lot of basalt from higher in the mountains. It’s been heavily calicified, cemented together with light-colored lime from groundwater.

The landslide deposits continue some distance west.

Further on, the road cuts through beds of the Chama-El Rito Member.

The Chama-El Rito Member is part of the Tesuque Formation, itself part of the Santa Fe Group. Working backwards, the Santa Fe Group includes all the rift fill sediments of the Rio Grande Rift, the great crack in the earth’s crust reaching from central Colorado to El Paso that roughly coincides with the valley of the Rio Grande. The Rift began to open about 30 million years ago, when the Coloradfo Plateau began to pull away from the rest of North America. Sediments immediately began to accumulate in the rift.

When North America began to drift onto the East Pacific Rise, a great upwelling in the earth’s mantle, the whole region was uplifted, and sediments began to be eroded back out of the Rift, exposing beds like the ones here.

The Tesuque Formation is the principal Santa Fe Group formation of the Espanola Basin. It is divided into a number of members, of which the Chama-El Rito Member seen here is characterized by the presence of bits of volcanic rock from the San Juan Mountains to the north and northwest.

Further up the road, we come to intact, solid beds of basalt.

This is a dark, dense rock showing occasional rusty spots. The latter are iddingsite, a weathering product of olivine, which in turn is a magnesium and iron rich silicate mineral. The presence of olivine shows that that this is olivine basalt, a low-silica volcanic rock in which olivine is able to form. Had the silicate content been slightly hit\gher, the olivine would have reacted with the silica to form pyroxene minerals, and there might even be a slight excess of silica to form quartz and make this a quartz basalt.

Such basalt is typical of the Lobato Mesa Formation. This is a body of volcanic rock erupted mostly between 11 and 9 million years ago in the northeast Jemez. The rock is mostly fairly poor in silica. Lava poor in silica tends to flow freely, and here it formed plateaus and low shield volcanos with relatively gentle slopes, subsequently eroded to form the more rugged peaks seen here today.

This

is a localized outcrop of rock with a peculiar appearance. On closer examination, I find it’s got a rotten texture, being easily pulled apart with the fingers. I’m guessing this is rock altered by hydothermal processes in the volcano.

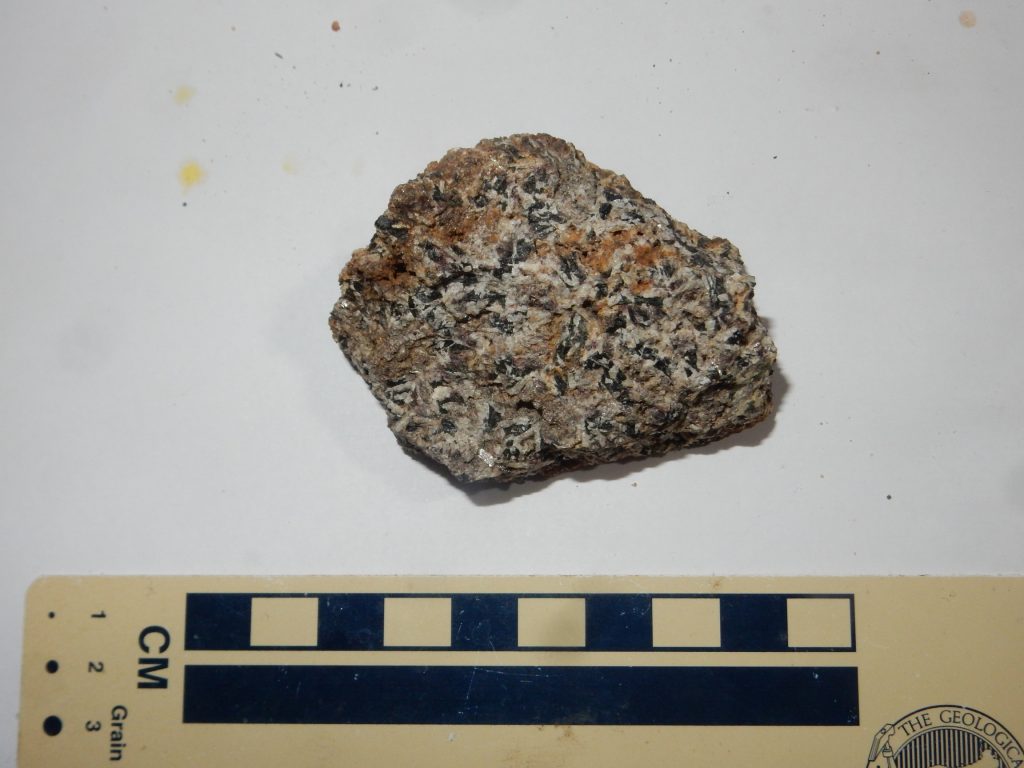

Yet further up is a celebrated outcrop of gabbro.

Some of the gabbro is very coarse grained.

I grab a sample, then look for the transition from gabbro to basalt. The two rocks have the same composition; the difference is purely in texture. I cannot find the contact I thought I saw last week; the coarse gabbro transitions smoothly to fine-grained basalt.

Gabbro likely formed in the very throat of the volcano, where magma had a long time to cool and crystallize slowly into coarse-grained rock. The dark grains here are pyroxene, an iron- and magnesium-rich silicate mineral, and the white grains are plagioclase feldspar.

I get a better photograph of the hydrothermal chimney I found last time.

The previous photograph was one of the ones spoiled by my malfunctioning autofocus.

Another better take of a previously spoiled photo: A cinder bed.

This shows that this area was part of a shield volcano, with alternating flows and cinder.

I hope I finally have this panorama right.

This is my fourth attempt at a good panorama from this location. The first was too late in the day so the right side was washed out. The second was in poor weather and early in the day. The third, last week, fell victim to the autofocus failure. This one is probaby finally good enough.

At left in the distance is the Sangre de Cristo Range. The middle distance is the Espanola Basin, with the nearer terrain underlain b Puye Formation with the pumice mine prominent. At center is south towards Sandia Crest in the far distance. At right the Tschicoma Highlands, including a view up Santa Clara Canyon.

When I hiked the trail to Clara Peak last week, I found that most of the road was reasonable for my vehicle. I drive clear to the base of the summit cone this time, pausing for an artsy picture south

This is another one I tried last week that didn’t focus. The summit cone, ditto:

I don’t climb clear to the top; I’m beginning to watch my time. (It’s already past noon.) I go as far as the switchback and take a panorama north.

This looks across the uninhabited badlands between Lobato Mesa at left and the Rio Chama valley at right. The terrain is hills and arroyos carved into the Tesuque Formation.

I hike back to my car, eat lunch, and head towards Tschicoma Peak. It seems like a beautiful day to scale the peak, the highest in the Jemez, and take some more panoramas.

A sedimentary formation in a road cut.

This, and similar deposits in the area, are mapped as Puye Formation. This is thick beds of mudflows and debris flows from the young Tschicoma Highlands. The young volcanic terrain was covered with volcanic debris that easily weathered away. Debris flows, roughly speaking, are rockslides lubricated by water; mudflows are just that, flows of muddy debris containing fewer large rocks.

A view of La Cuchilla de la Monjonera, “Monjonera Ridge.” I can find no translation for Monjonera, so I suspect it is a proper name.

The more distant ridge left of center is part of Lobato Mesa.

The road ascends Mesa de la Gallina, “Chicken Mesa”, a single enormous dacite flow covering the northeast flank of Tschicoma Peak. Visible below is a striking goblin colony.

As with most photographs at this site, you can click to enlarge. The “goblins” are eroded in Tschicoma Formation dacite.

Further up the mesa, there is a view to the south of a lag field on the north side of an unnamed dome.

A lag field is a field of rock fragments of similar size, from which high-energy erosion has removed all the smaller fragments. There are a number of lag fields in the Jemez, usually on high-silica domes where rubble was generated in large quantities when the dome was erupted. Some show signs of having accumulated enough ice during the last Ice Age to be transformed into rock glaciers. The satellite view of this one shows some signs of flow down the side of the mountains, suggesting it was a rock glacier at some point in the past. We’ll see a much more clear cut example of a rock glacier in my next post.

My ultimate destination, Tschicoma Peak.

Note the many burned and downed trees. These were burned in the Oso Complex Fire of 1998.

I am not aware of any established trail to the summit, but the approaches are not steep anywhere to the north or west. I have a vague recollection of seeing a logging road that approaches the summit from the west. Is this it?

It turns out it is, but I can’t be sure of that at the time and it seems a ways from the summit. I head back east, and see what looks like a trailhead.

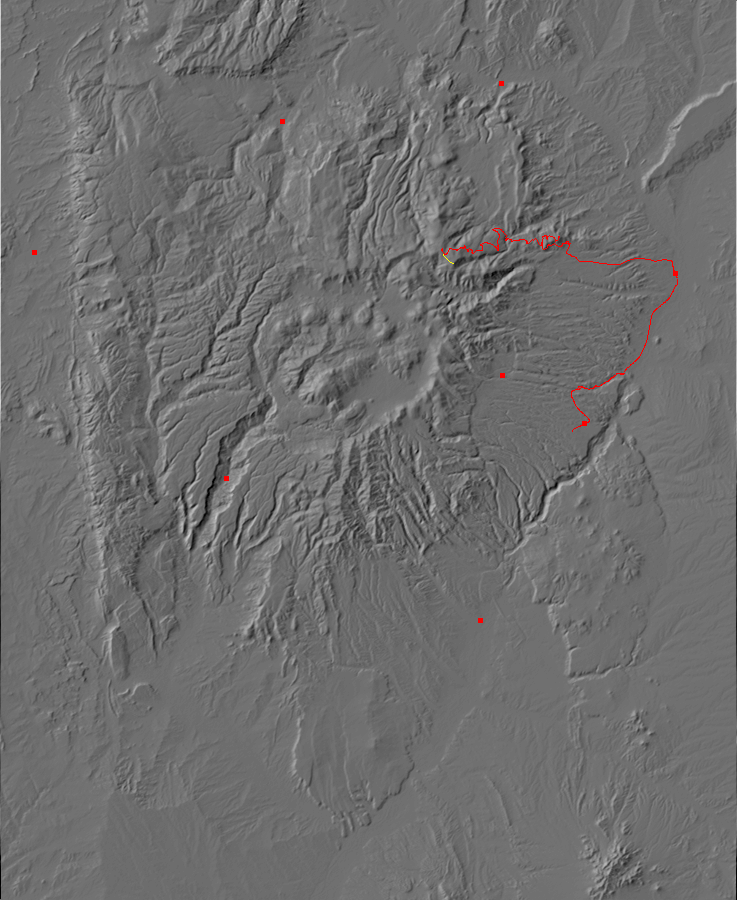

Well, all right, then. I load up, hit the track button on my Spot-3, and start up the trail. Which quickly peters out. Which is not actually much of a problem; this is very old growth forest, with little underbrush, and it is easy to bushwack. I’m headed for the highest point int the Jemez; really, all I have to do is head uphill, and sooner or later I’ll get there.

Sure enough, before long, I hit a logging road.

It’s headed uphill and more or less towards the peak. I have nothing to lose by following it.

A fork:

The right fork ascends faster. Again, I can’t really go wrong following it.

Detroitus.

The road eventually fades, but there are fresh tracks of an ATV continuing on. On a hunch that they may have been headed for the summit, I follow the tracks. They eventually fade, and I find myself on what looks like level ground. The summit?

My recollection from Google Maps is that the summit is forested, with a big open meadow just to the south. I head that way, and find an impressive fungus …

..but the forest shows no signs of opening up. I decide this cannot be right and that I am still too far west. (Both correct.) I head east, and, sure enough, the ground begins to rise again. I stay slightly to the right, since that’s where I should hit the meadow, and sure enough:

This is obviously very near the summit. “Success, my lord!”

I climb to the top of the meadow for my first summit panorama of the day.

Hmm. Somewhat marred by a passing cloud shadow. Still. At left are rhyolite domes filling the Toledo Embayment, an embayment in the northwest wall of the Valles caldera that no one seems to fully understand. The domes were emplaced after the Toledo eruption 1.62 million years ago but before the Valles eruption 1.25 million years ago.

Left of center is the north rim of the caldera and the embayment.

In the further distance from left of center to center is the La Grulla Plaeau, an andesite plateau some 8 million years old. Beyond it on the furthest skyline are the San Pedro Mountains.

At right is Cerr Pedernal, the small sharp peak, and to its right and closer to the camera is Polvadera Peak, the third highest point in the Jemez Mountains. Like Tschicoma Peak, it is around 3 million years old and is underlain by dacite of the Tschicoma Formation.

I continue up, bearing a little right so I will come out on the south meadow. There is a little conversation running through my head:

You gotta go to the peak.

No I don’t. It’s timbered and has no good views.

You can’t come this far and not go to the peak.

Sure I can. There’s nothing interesting to photograph at the peak.

Pphhhhhth.

It’s moot. A moment later I come into a clearing, and …

Someone has gone to a lot of trouble to mark the peak.

Maybe. Google Maps puts the peak about a hundred yards to the northeast. The peak is so gentle it hardly matters.

It looks like someone has also built a trail.

Maybe not. The trail goes towards a very steep slope that doesn’t actually go anywhere.

I head south, finding the meadow. Time for another panorama.

In the distance at left is the city of Los Alamos. The ridge at left center blocking the view of part of the city is Caballo Mountain. To its right and more distant is Pajarito Mountain, with its many ski runs. To the right in the far distance is the south rim of the calder, with Redondo Peak slightly closer at far right.

The are right of center in the middle distance is Shell Mountain.

The flat mesasin front of Shell Mountain and to its left are underlain by great thicknesses of Bandelier Tuff from the Valles eruption. Shell Mountain itself, at upper right, is underlain by Cerro Toledo rhyolite from between the Valles and Toledo eruptions, but the dome to its left is older Tschicoma Formation dacite. The dome just visible beyond this dome is Cerro Rubio, underlain by Tshicoma Formation dacite.

Los Alamos.

Looking past Shell Mountain.

Beyond Shell Mountain, in the middle distance, is Cerro del Medio within the caldera. This was the first of the ring fracture domes to erupt, when magma penetrated the ring fracture around the plug of rock (thirteen miles across) that collapsed into the underlying magma chamber when the Valles eruption emptied the chamber. Beyond Cerro del Medio on the skyline is the south rim of the caldera.

Now all I have to do is figure out how to get back to my car. Going up was easy; just keep going up. But there are now lots of directions that are down. Fortunately, I have a trail of GPS fixes, like bread crumbs leading back to my car, and it turns out not to be too bad.

One more shot on the way out, of Lobato Mesa, “Wolf Cub Mesa”.

Lobato Mesa is the ridge furthest to the east. The rest of the plateau here is properly known as Mesa Alta. The northern end is owned by Abiquiu Pueblo, but the edges and southern end are National Forest. The plateau is underlain mostly by Lobato Mesa Formation basalt. It’s a beautiful area.

From there home.