One-eye wanderlust

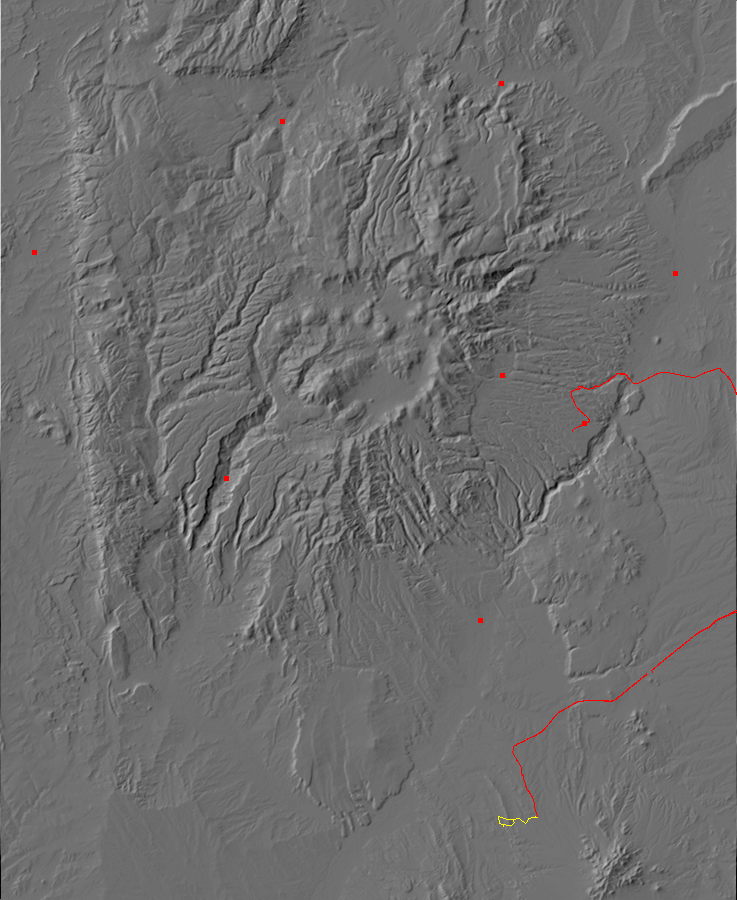

Yesterday was an absolutely gorgeous day, starting out warm with hardly a cloud in the sky. It was just too good a day not to go hiking. I had postponed the annual Kent Is No Longer 29 wanderlust both because the weather was not great and because I could not invite anyone to join me, because of the pandemic. But it may be that way for a while, so yesterday’s hike will have to do for this year.

I chose the Arroyo del Tuerto for this hike, because it sounded like a geologically interesting area and it’s isolated enough that I can be confident that hiking it will maintain appropriate social distancing. I was also under the mistaken impression that Arroy del Tuerto translates as Valley of Death, which seemed fitting, but a double-check reveals that it means One-eyed Valley. Well, close enough.

So I head out, drive past Santa Fe, and look for the old Budagher’s shopping center. This is a sad little monument to the optimism and excesses of venture capital of the 1990s, built (I suppose) on the theory that a big tourist trap on the interstate halfway between Albuquerque and Santa Fe was just the thing to rake in dollars. It opened to great hype, and Cindy and I did some Christmas shopping there; we were not impressed and never went back. It quickly went bankrupt and is now abandoned.

This turns out to be the wrong exit. I thought this was my road south, but dead ends on private property. It turns out I wanted the Santo Domingo Pueblo exit further north. I only figure this out because I have a trail guide to consult; I suppose I should have consulted it in the first place. The road has been paved, but not for decades. It’s still pretty good for a gravel road, indicating that the highway department has made a conscious decision to let it go back to well-maintained gravel.

The Arroyo del Tuerto trail is located on BLM land, but it is more or less surrounded by tribal lands. This means the trail head is reached via an easement road, and the easement road has a locked gate. You have to drive to the BLM office in Albuquerque for the key.

I do not have the key. I’m sure the BLM office is closed due to the pandemic. Also, that would mean wasting daylight driving to Albuquerque and trying to find the office. Hiking from the gate would add an extra five miles to the round trip, making it a nine-mile hike, but I had already decided that was okay.

Nothing on the signs says it’s illegal to squeeze through the gate; only that you have to keep the gate locked at all times and that you musn’t leave the road until you reach BLM land. Well, and a big sign warning you not to take or destroy anything. Normally one is allowed to collect rocks on BLM land, within reason, but I decide to refrain from rock collecting this trip. I suspect this warning is here to protect the petrified wood and Stearns fossil quarry.

The Stearns quarry is the best fossil bed in the Galisteo Formation, an Eocene formation (56 to 33.9 million years ago) that would otherwise be tough to date. The fossils here helped pin down its age. The quarry is off limits, as it should be, but the nearby petrified wood beds are not paleontologically critical and can be visited, so long as you don’t take any of the petrified wood.

I head down the road and, after a time, come across rocks in the road.

These appear to be heavily calicified (lime-coated) bits of monzonite from the nearby Ortiz Mountains. This suggests I’m standing on the Ortiz surface, the original example of a pediment surface eroded at the foot of a mountain range in an arid climate. Pediment surfaces are typically paved with a calicified gravel, which in this case is known as the Tuerto Gravel.

As with most images at this site, you can click to embiggen.

Yeah, I know. But the first half of the hike is going to be pretty much getting from point A to point B with limited geologic interest. It gets much better after that.

Some reminders to stick to the road.

I can’t really blame the tribal governments for being protective of their land.

Some more clasts.

The black needles are hornblende. They are embedded in a light matrix of mixed plagioclase and potassium feldspar. This is a pretty common rock type in the Ortiz Mountains, which started out as laccoliths or big intrusions of magma that penetrated between sedimentary rock layers and domed up the overlying ground. In some cases the magma broke through to the surface to build volcanoes. Radiometric dating indicates most of this activity took place around 35 million years ago, about the same time as a great wave of igneous activity across the western United States. This is known as the mid-Tertiary ignimbrite flareup, and its cause is still being worked out by geologists.

First fork. I am reassured that the signage is very clear.

I was never in any danger of taking a wrong turn before reaching the Arroyo del Tuerto trail head.

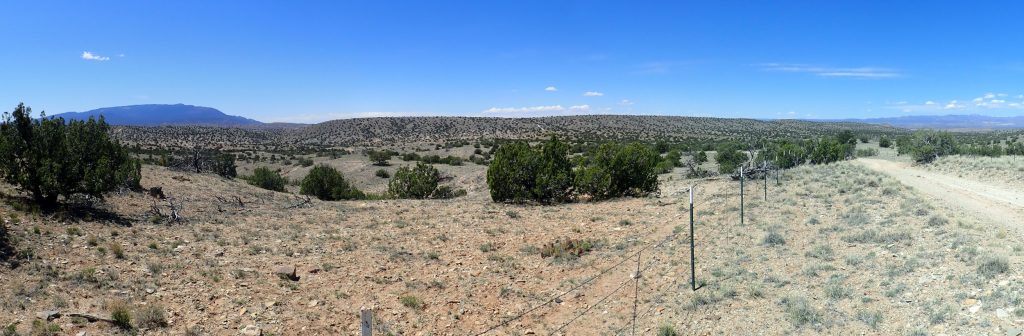

Since I’ve mentioned them a couple of times already: View of the Ortiz Mountains to the southeast.

Ahead I get my first glimpse of Espinaso Ridge, through which Arroyo del Tuerto cuts.

Espinaso (“Spine”) Ridge is a long north-south ridge that does indeed look a little like a backbone. In fact, it is what geologists call a hogback ridge, formed where sedimentary beds have been steeply tilted and a particularly resistant bed stands out as softer beds above and below are eroded away. The resistant beds here belong to the Espinaso Formation, which are rich in volcanic ash from the volcanoes of the Ortiz Mountains. Volcanic ash contains amorphous silica that forms a strong geologic cement.

I come to a little valley, which is the first break from the rather flat ground covered with pinon and juniper scrub that has been my hike up to now.

Here the Tuerto Gravel has been eroded through to expose the underlying Santa Fe Group rift fill sediments. We are in a structurally interesting area, the Hagen Basin, which is a region where a big block of crust has dropped and been tilted to the east. It is bounded on the east by the La Bajada Fault, which produces an escarpment from here north that marks the easternmost edge of the Rio Grande Rift north of this latitude. On the west, the block is bounded by the San Francisco Fault, which becomes the eastern margin of the Rio Grande Rift south of this latitude. We are in an accomodation zone where the rifting shifts fairly abruptly to the right as you down the rift.

The dropping and tilting of the crust here created a basin in which sediments began accumulating, beginning around 20 million years ago. These are assigned to the Santa Fe Group, and the beds exposed here are assigned to the conglomerate and sandstone piedmont facies of the Santa Fe Group. Unpacking that: The sediments come from the Ortiz Mountains and are rich in bits of volcanic rock and sand, making for rather coarse sediments.

Espinaso Ridge comes into view in all its glory.

Arroy del Tuerto itself is at left, where cuts through Espinaso Ridge.

Here the road begins its descent off the Ortiz surface to the exposed Santa Fe Group beds beneath. You can see that the road is cut in light soil, full of caliche, while the underlying sediments are a darker red color.

One last clast of monzonite from the Ortiz Mountains before leaving the Ortiz surface.

And I reach the gate where the easement road enters BLM land.

The hike from the locked gate back where I left my car is a balloon hike, and just ahead is the base of the balloon.

Horses.

These are probably mustangs, feral horses. People being sentimental about such things, they have special protected status on BLM land. In this area, this means that piles of horse manure are all over the place. There is some kind of legal process for adopting one, but it’s probably considerably less hassle to just buy your daughter a pony, if you have that kind of money and that kind of daughter.

The balloon point. I will turn left here, make a loop, return to this point from the other direction, then return the way I came in.

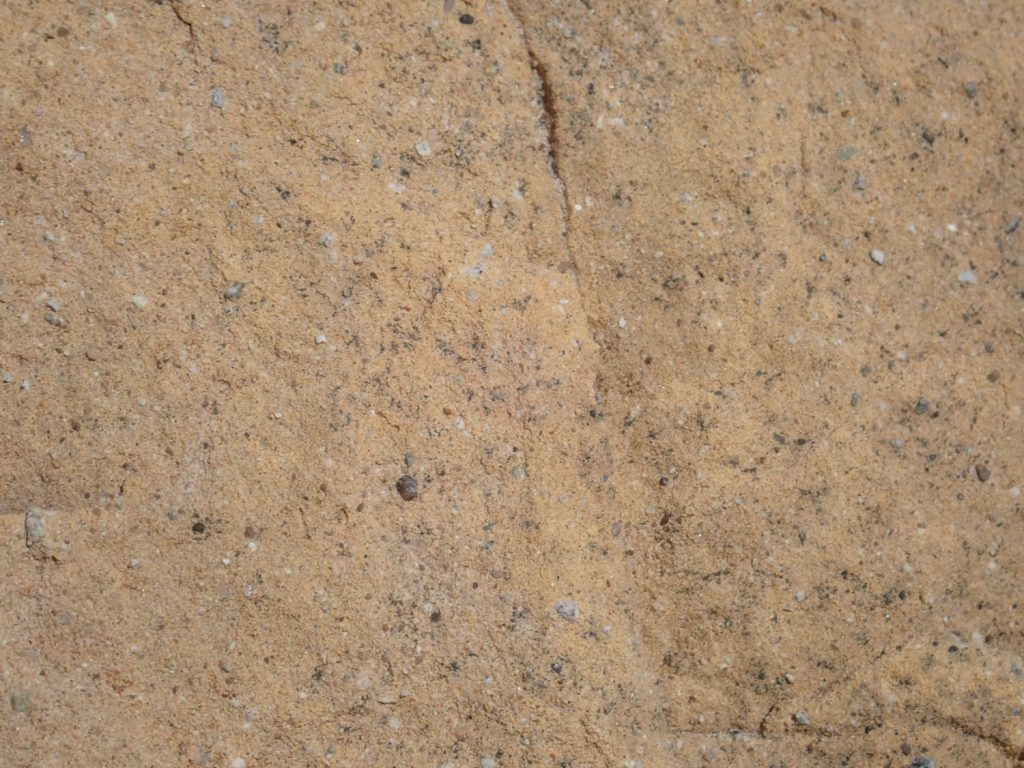

My first real outcrop of the day.

This is mapped as basin floor sediments, mostly dirty sandstone. At another location, there is an interbedded basalt flow that has been dated as 25 million years old. This was when the Hagan Basin was first forming, and the area was floodplain and ponds with flow generally towards the north. Later, flow would switch towards the west and bring in sediments from the Ortiz Mountains.

The parking area and trail head, where I could have started my hike if I had borrowed the gate key.

I pause here to eat my lunch. I’m mildly curious about the windmill, which occasionally makes a mournful noise as the wind picks up just enough to turn it. The associated tank is bone dry. It turns out the top half of the windmill shaft has been removed, putting it out of commission.

I resume my hike.

I will stick to the arroyo, where most of the interesting geology is. This means skipping some trails alongside the arroyo. My trail guide will prove moderately useful when I reach the far end of the arroyo, particularly for locating the petrified wood beds.

I spot some sandstone beds to the north.

This seems worth a closer look.

A well-cemented but poorly sorted sandstone. My map is unclear what this is. Stratigraphically, it has to be older than the basin fill unit, but that’s supposedly the oldest rift sediment unit here.

And I goof resetting my camera after the close up. This makes a whole lot of the pictures that follow less than perfect. But still usable.

The beds have a pretty good dip to the east.

This shows that the Hagen block was tilted after it dropped enough to begin accumulating sediments. The geologic guide for this area notes that there is a sharp angular uncomformity separating lower Santa Fe Group from upper Santa Fe Group in this area; that may be when the block became tilted. The tilting would also have coincided with a period of erosion that leveled off the beds. My guess? The uplift of the Sandia Mountains to the south, which we know are relatively young mountains.

More tilted beds.

Here a resistant sandstone bed cuts across the arroyo.

A pebbly, poorly sorted sandsone. That describes much of the Santa Fe Group. The presence of monzonite clasts confirms that deposition in this basin postdated the Ortiz volcanic field.

Approaching the ridge itself, which is underlain by relatively dark rock of the Espinaso Formation.

At this point, we have reached the upper surface of the Espinaso Formation, marked by a transition to debris flow beds and ash beds.

At the mouth of the slot canyon.

This was a debris flow off the slopes of the Ortiz volcanoes.

More volcaniclastics, always dipping to the east.

The Espinaso Formation is 400′ thick and was deposited between 36 and 25 million years ago. It looks a lot like the Puye Formation along the road to Los Alamos. Both are volcaniclastic aprons eroded off of high-silica volcanic mountains. However, the Puye Formation is around 3 to 5 million years old, making it much younger than the Espinaso Formation.

The arroyo crosses a resistant ledge.

Nearby is a bed of very coarse boulders — and signs of geologists at work.

Look at all the sampling boreholes in the rocks.

Here we have what looks like an ash bed overlying a debris flow.

Look at the size of the one boulder. A line from my wasted geeky youth comes to mind: “That’s no moon.”

More.

Here we have a pair of tuff beds sandwiched between debris flows.

The lower tuff flow is very lithic-rich.

In the Jemez, such tuff tends to be associated with caldera collapse. I know of no other evidence of caldera collapse in the Ortiz Mountains.

It’s just one Ansel Adams moment after another.

Nearing the west end of the slot canyon.

Notice the reddish color of some of the beds. We are nearing the bottom of the Espinaso Formation, and the underlying Galisteo Formation includes red beds. We are starting to see some interfingering here.

Still mapped as Espinaso Formation, but we’re definitely nearing thebottom.

Here is about where the map puts the contact.

The Galisteo Formation is Eocene, about 40 million years old, as confirmed by fossil remains from the Stearns quarry just south of here. It is a sedimentary formation formed in a river flood plain in what must have been a fairly hot environment, judging from the many red beds in the formation.

And here the dip seems to abruptly reverse, to the west.

I look in the other direction, and, sure enough, the Espinaso Formation beds seem to level out.

I find myself wondering if Espinaso Ridge is a monocline, rather than hogback. A monocline forms where sedimentary beds drape over a fault in the basement rock, and there’s certainly plenty of potential for such a fault here. But no; I’m just out of my reckoning. I have been turned 90 degrees. I’m now looking directly east at the Espinaso beds.

This is definitely Galisteo Formation.

And horses have definitely been in the area recently.

Not all Galisteo beds are red beds. The formation is quite variable in color.

According to my trail guide, I should soon start climbing south out of the arroyo to find the road to the petrified wood beds. I find that I’ve actually come just past the right point, but soon find the road.

There are striking Galisteo red beds to the west.

The road hits a junction at which one turns left.

The trail guide says to look for a clearing to the right, beyond which are odd-looking boulders. Here it is.

A faint trail has now been beaten up the hill, where I find numerous large pieces of petrified wood.

Now let me pause for a little sermon. Yeah, I know, but.

I did not take home any petrified wood from this location. Collecting ordinary rocks and minerals on public lands, other than national parks and monuments, is legal and of course I do it often. Ditto collecting common invertebrate fossils. Petrified wood of this quality is unusual enough that I do not normally collect it off of public lands, and I urge you not to as well. I know geologists who will not disclose locations of petrified wood or other choice fossils. I’ve posted this location because it has already been widely published by others, and it’s hard enough to get to that I’m not too worried. Please don’t make me regret it.

Rick and Shari Kelley once showed me a photograph of them standing over a twenty-foot log of petrified wood, beautifully preserved, somewhere in northern New Mexico. When I asked where this was, the response was “Ain’t tellin.'” I really don’t blame them.

That’s enough sermonizing, so back to these pieces. They are located in the uppermost Galisteo Formation, but still well below the Espinaso Formation. Petrified forests are often associated with volcanic activity that produces abundant volcanic ash. This is unsurprising given that volcanic ash contains ample amorphous silica, which dissolves and moves through groundwater to fill pore spaces in organic matter and thus petrify it. Lamar Valley in Yellowstone has extensive petrified forests formed in this way. Petrified Forest in Arizona was likely petrified by silica from the Mogollon volcanic arc to the south.

It’s likely the volcanic ash of the Espinaso Formation provided the silica to preserve these pieces, which appear to have already been partly decomposed when they were petrified. How long an interval between the deaths of theses trees and the eruption of the Espinaso Formation? It could not have been long since wood rapidly decays. The Stearns Quarry south of here has fossils not less than 38 million years old. The oldest Espinaso Formation beds are about 36 million years old. It wouild not take much to close that gap. So we may be looking at victims of the very first catastrophic eruptions out of the Ortiz volcanoes.

From this hillside, there’s a wonderful view of Espinaso Ridge to the east.

Spring is well under way here. Desert marigold:

Desert indian paintbrush.

I climb the rise to the west.

Here we see the full variability in the Galisteo Formation. White beds are relatively pure sand. Gray marks beds that were rich in organic matter. Red beds were formed under hot, likely arid, conditions where very little organic matter is deposited with the sediments.The climate seems to have fluctuated significantly in Eocene time.

I climb down the hill to the north, whre I can see the road, and retrace to the arroyo.

Note that the tilted beds of Galisteo Formation are capped with level gravel beds. These are mapped as young river alluvium.

A striking resistant bed.

This divides whitish beds to the left from red mudstone to the right. I wonder what happened here.

The arroyo continues west and, if followed, would take me to a wonderful succession of increasingly old formations, going clear back to the Jurassic. Alas, much of this is on tribal land. Also, my time is running out. I am beginning to wonder if I have come too far, and missed the road crossing the arroyo that I am supposed to take next. I get particularly concerned when I see what looks like a boundary marker ahead. Fortunately, this turns out to mark my road.

I turn right and begin my homeward leg.

The road passes through impressive red beds.

Closer view.

I reach the easement road.

From here it’s east back to my car, and I admit I’m starting to feel tired and ready to go home. But I still have to cross Espinaso Ridge.

It is a bit of an obstacle.

This caught my eye, though I am now tired enough I’m having trouble pointing the camera straight:

The contact between the red beds above and white beds below is clearly an erosional surface. I’m guessing it’s young, with recently eroded sediments above a calicified surface, rather than an ancient discomformity within the Galisteo Formation, but I’m too tired to go over for a closer look.

The road ascends the ridge. (Sigh).

On the plus side, the view really opens up to the west.

I am looking into the western side of the Hagen Basin and into the Rio Grande Valley beyond. Somewhere to my left is the ghost town of Hagen, where coal was once mined for the railroad from the Cretaceous Menifee Formation. Sandia Crest is prominent.

The summit of Espinaso Ridge.

View to the east.

I am now looking into the eastern half of Hagen Basin. You can see the very flat Ortiz Surface at right, around the Ortiz Mountains. At left are the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, and the Cerros del Rio is at far left. The Bajada Fault runs just west of the Cerros del Rio, but its escarpment cannot be made out from here.

Back to the balloon point.

Wildflower. Cushion cryptantha, perhaps.

And finally, back in view of the car. Which is still there, has no flat tires, and has no nasty-note on the windshield. (I was worried a bit about each.)

I drive home, skipping the usual stop at Trader Joe’s for the obvious reason. There are two “emergency alert” stay-home messages on my cell phone. There are signs along the highway north of Santa Fe telling Easter walkers to the Chimayo sanctuary to turn around; it’s closed because of the pandemic.

I arrive home tired and, I confess, a tetch grumpy. I find a lot of lawn and flowers needing mowing and watering, and I have to water by hand, because the valve tree for the sprinkler system has developed a crack, and if I can’t figure out how to seal it, I’ll have to rebuild the valve tree, a thought that does not improve my mood.

Will work on finding ways to improve my mood.