Wanderlusting the Moppin Complex

This is the oldest rock I’ve visited in New Mexico; twice now. I was hoping third time would be the charm.

So Saturday I loaded up and headed the Wandermobile north to the Tusas Mountains again. My goal was to try to find pillow lava structure in the Moppin Complex at Iron Mountain, and visit the type section of the Salitral Formation and an exposure of the Rock Point Formation on the return trip.

Let’s unpack that for the benefit of newer readers. (Welcome!) The Moppin Complex is a body of rock exposed in a belt through the northern Tusas Mountains. It’s mostly composed of amphibolite and greenschist, two relatively silica-poor rock types that are usually formed when basalt — the familiar black lava rock that makes up much of Hawaii, the Malpais in New Mexico, and many other volcanic landforms — is recrystallized by great heat and pressure deep underground. Geologists believe, based on radiometric dating, that this rock is about 1.755 billion years old. That makes it as old as any rock in New Mexico. Other subtle chemical clues suggest it formed as part of a volcanic island arc in an ocean basin. It then drifted into the southern margin of what would become North America, forming a belt of crust (the Yavapai Province) reaching from southern Wyoming to northern New Mexico and from Arizona to the Midwest. And perhaps beyond: Rocks that may be a continuation of this belt are found in Antarctica and the Baltic.

Pillow lava forms when lava erupts in deep water. It’s characteristic of island volcanism.

The Salitral and Rock Point Formations are much younger rock, and since I ended up not having enough time to visit them this trip, I’ll save that for a future post.

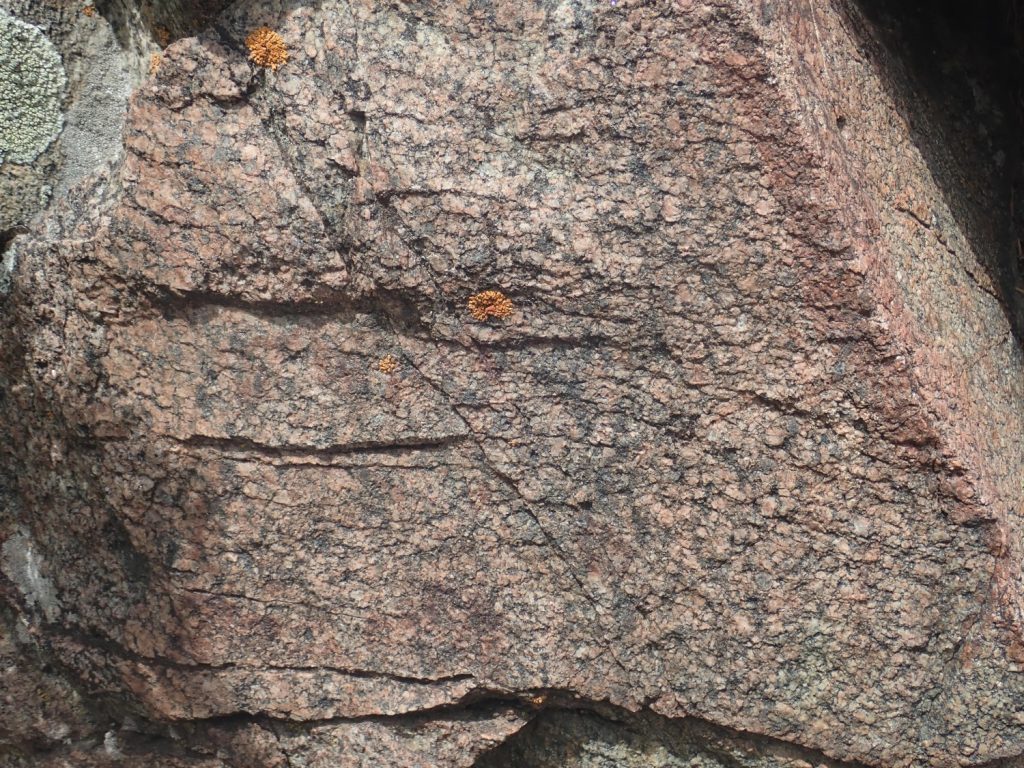

I drive north past Espanola and Ojo Caliente to Tres Piedras. Here there are outcroppings of the Tres Piedras Orthogneiss, a granite-like rock that is only slightly younger than the Moppin Complex. Although I was here recently, and good some good photos and a sample of an outcrop, I wasn’t entirely happy with my photos. I want a clear shot of a really big outcrop, without vegetation or buildings in the way. On a hunch, I follow a forest road to a rather large outcrop. I find a place to park, then try to find a clear view.

It’s better than any previous picture I’ve taken, but there’s still a lot of foreground vegetation. Darn, there’s a barbed wire fence blocking the direct approach. I head back to the dirt road and walk west, to discover that this is a trailhead for rock climbers. There are large exposures of the formation at ground level

Oh, and before I forget: For new readers: Almost every image at this site can be clicked for a high-resolution version, and almost all blue links take you to the location on Google Maps.

A short hike gives the best view yet.

That’s definitely one for the book. I can see why climbers come here, though I didn’t actually see anyone on the rock. (There were cars at the trail head.)

The Tres Piedras Orthogneiss is about 1.693 billion years old and has the composition of granite. It was probably injected as a body of magma deep underground during the Yavapai Orogeny, the name geologists give the collision that joined the Yavapai Province to North America. The rock cooled and solidified, only to be deformed and recrystallized (making it a orthogneiss) during the subsequent Mazatzal and Picuris Orogenies. The Mazatzal occurred not long after the Yavapai, around 1.65 billion years ago, while the Picuris Orogeny occurred 1.45 billion years ago and was quite violent, deforming the crust clear to Wyoming.

The next stop was just for the heck of it.

This is the Esquibel Member of the Los Pinos Formation. It’s somewhere in the ballpart of 15 to 20 million years old and is sediments eroded off the San Juan Mountains to the northwest when they were young volcanoes.

I come to my turn to Iron Hill, wondering if the gate will be open. No, but at least I now know why:

Crep. Well, I imagine my friend Gary considers elk calving a worthy cause.

I consider. There’s no apparent prohibition on hiking into the area. It would be time-consuming but I need the exercise. And by July 25 monsoon season will be active. I decide to walk.

Before long, I come to what looks like a dike or other long outcrop.

This turns out to be a granitic rock of some kind.

There are four possibilities. This could be an outlier of the Tres Piedras Orthogneiss, which it rather resembles. Or it could be Burned Mountain Formation, though it looks too pristine — Burned Mountain Formation is so heavily metamorphosed that it is more of a muscovite schist. It could be a formation I’m not familiar with. Or it could be the Maquinita Granodiorite, which intrudes the Moppin Complex in many locations. It’s actually the Maquinita Granodiorite we know the age of radiometrically, so all we can really say is that the Moppin Complex it has intruded is not younger than 1.755 billion years. But this doesn’t look like other Maquinita Granodiorite outcrops I’ve seen; too pink. The granodiorite tends to be gray.

But it turns out that’s what it is, when I get home and check coordinates against the geologic map.

Our best interpretation is that the Maquinita Granodiorite was part of the original island arc and may represent late higher-silica magma chambers. A granodiorite has some quartz but is mostly sodic plagioclase feldspar with not much potassium feldspar. It’s usually potassium feldspar that is pink.

I look over it some more.

This looks more like granodiorite.

There’s more at the end of the valley.

Maybe. Most metamorphic rock has that shaggy look. The deformation foliates it, and since there’s pretty much nowhere for it to go but up, the foliation is very often close to vertical — subertical in the jargon. But I’m in a rush and decide it’s not worth walking over for a closer look. Turns out, when I get home, the map confirms this is more granodiorite.

I pass some more Los Pinos beds, then some more granodiorite,

and then to a road intersection with flat ground for camping I had memorized as my next turn. Someone’s already there:

I think Wait, what? The gate was locked for elk calving season. How’d he get in here? But it turns out the vehicle has a NMSU plackard on the side. Probably legit; a researcher of some kind. Like me, but official.

Just beyond is Iron Mountain, or at least I think so. The location was specified by range, township, and section in one geological paper.

Range and township is a rather old system for specifying locations, dating back to the homesteading days. But it is still used for legal descriptions of parcels of land and by geologists. I think I was able to correctly find it on a map, and the geologic map says that the large hill there is indeed underlain by Moppin Complex. Iron Mountain is where relict igneous structures, including pillow lavas, are supposed to be discernible in the beds.

So here we are.

This looks like more Maquinita Granodiorite, likely a local intrusion. Perhaps this also.

Beyond is definitely Moppin Complex amphibolite or greenschist.

My guess is that the best-preserved structures would be towards the top of the ridge (it is only a guess) and my plan is to walk to the top and work my way along it. There are indeed some striking outcrops here.

This shows all the signs of highly deformed rock, and, to be honest, I’m not sure I’d know relict pillow lava structure if it clubbed me over the head. I know what pillow lava looks like when well-preserved, but I’m not sure anything here is going to be very well preserved.

This is a little more massive.

as is this.

If I squint real hard, I can imagine I see some primary structure in the first photo … but probably not.

This is interesting.

This doesn’t have the coarse grains of Maquinita Granodiorite. It’s much fintger-grained. This may be a local intrusion of Burned Mountain Rhyolite, which is about 1.70 billion years old.

Past that, I’m back into Moppin Complex. I continue east, fairly thoroughly scrutinizing all visible outcrops for signs of primary structure. Primary structure: That’s the structure of the rock when it first erupted and cooled, and includes things like pillows.

I come across a prospect, where a prospector dug out a pit looking for possible valuable minerals. Perhaps magnetite schist:

The color and rusty weathering suggest iron-rich rock, and this hill is named Iron Mountain. Or perhaps not. The prospector may have been attracted by local thick quartz veins, which suggest gold mineralization.

Here’s the prospect, which may actually have had some significant mining.

I conclude that I’m finding nothing at the top of the ridge, and decide to work my way lower. The rock does indeed show some difference. This outcrop is a bit more granular.

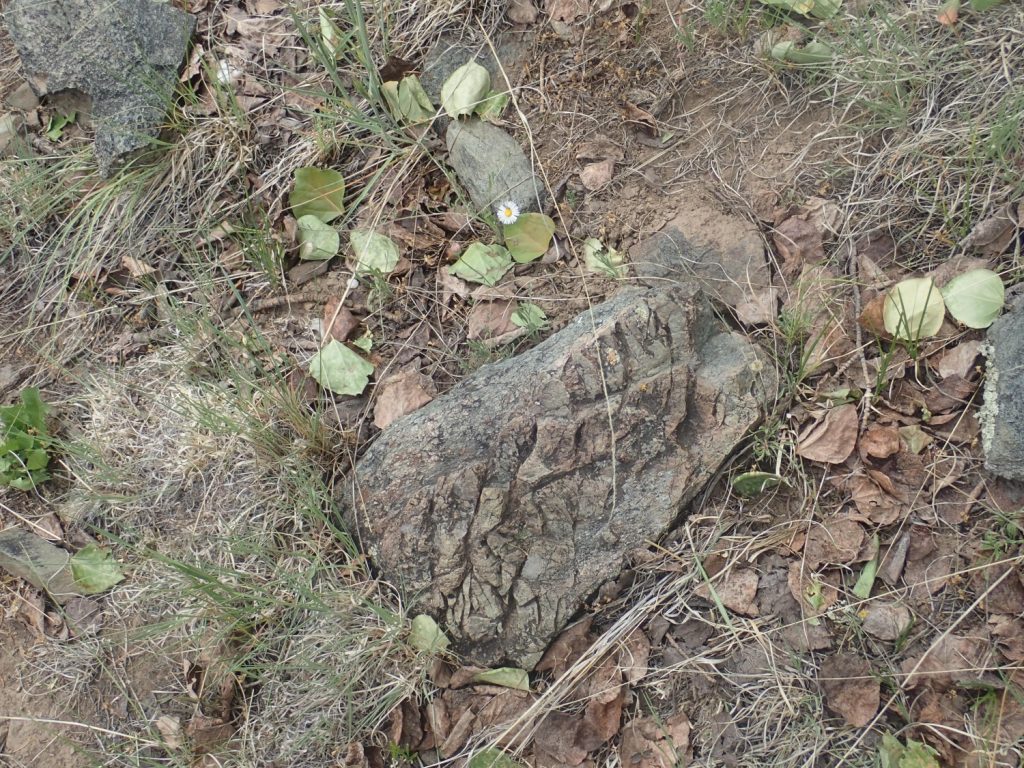

This one shows some suggestive hints of structure other than the metamorphic jointing.

This is definitely some kind of structure, though not necessarily pillow lava.

This is a quartz dike that has been exposed along it side by erosion.

A pillow?

My time is running short if I want any time looking at the Salitral type section on the way home. I work my way down to the road at the base of the hill, hike just a little further along it to see if there is anything different, and notice obvious mine tailings below the road. I make a mental note to come back to these if there is time.

Nothing different down the road. I come back to the mine, consider, and decide I might as well take time to check it out.

There is some rather odd rock here, including what looks like mafic rock with felsic inclusions:

Mafic: Silica-poor, iron and magnesium-rich, and generally dark in color. Felsic: High in silica and containing abundant feldspar and quartz. Normally it’s the other way around in this area, with felsic intrusions containing bits of mafic rock.

Possible structure here.

The mine entrance.

The tailings.

There’s a lot of reddish color here, which, together with the epithet Iron Mountain, makes me think they were digging for magnetite schist here.

Time is runnin short. I hurry back to my car, then continue west and towards home. The road takes me past the Brazos Cliffs.

Underlain by Ortega Formation quartize, the youngest formation we’ve seen so far, though only by a slim margin. Perhaps 1.65 billion years old.

And then I get stuck in road construction, and decide I just don’t have time to do my other schedule stops justice. Perhaps this coming long weekend.

I return home having found no convincing pillow structure nor visited the other two formations, but I did get an unexpectedly good look at the Tres Piedras Orthgneiss and the Maquinita Granodiorite. You win some, you lose some.