90th Birthday Wanderlust, Day 19: Bright Angel Trail

We wake, breakfast, and break camp. The weather is overcast, but that may be a good thing: We are planning on hiking the Bright Angel Trail.

We will not be hiking all the way to the canyon bottom. That’s 16 miles round trip with more than a little change of elevation, and I am no longer a young man. I could almost convince myself to try for Indian Gardens, which is about 11 miles, but we decide to strike for Three Mile Resthouse for a six mile hike. Subject to modification as we see how we are doing.

The canyon below.

We don packs and begin the hike. As the cliche goes, it’s a journey backwards in time. The uppermost formation on the trail is the Kaibab Limestone.

This formation is Permian, around 260 million years old. As you would guess from its name, it is mostly limestone, but it’s a pretty dirty limestone, interbedded with some layers of sandstone and mudstone. It is thought to have been deposited on a gently sloping continental shelf, subject to fluctuating sea levels. The continents were then joined into the great continent of Pangaea, and this area was on its northwest shore, not far north of the equator.

A likely fossil in the limestone.

Below the Kaibab Limestone is the Toroweap Formation. This is also Permian, but slightly older at around 270 million years in age. This formation is composed of mostly gypsum and shale, with some sandstone, deposited near the shore as the sea began to retreat.

Because shale and gypsum are not very resistant to erosion, the formation is poorly exposed, mostly forming a slope covered with soil.

Below the Toroweap is the Coconino Sandstone.

The Coconino is also Permian in age, but yet older, at around 275 million years old. It forms a great cliff below the rim of the Grand Canyon through most of its length. It’s a well-sorted eolian sandstone, deposited by wind, likely sourced from beach sand brought to the northwest by rivers flowing off the Central Pangean Mountains — of which the Appalachians are a remnant.

My GPS is simply not functioning well in this deep canyon, so it’s hard to pinpoint exact locations along the trail. However, Google Maps actually has a street view of most of the trail, which allows me to reconstruct most location.

The trail crosses over into what looks like Kaibab Limestone.

It’s hard to be sure. But it turns out there is a large fault over which the trail switches back and forth, the Bright Angel Fault, which is thrown down to the east. So on the east legs of switchbacks, we may cross onto beds we’ve already seen, while west legs will jump us well down the stratigraphic column.

We’re definitely looking at a wall of Coconino here.

At top are cliffs of Kaibab Limestone, which are thinly bedded and tend to weather into columns. Below is a thin layer of Toroweap Formation, forming a short slope with lots of trees. Then the wall of Coconino. Below that, the red layer at the base of the cliff is Hermit Shale, which we’ll discuss shortly.

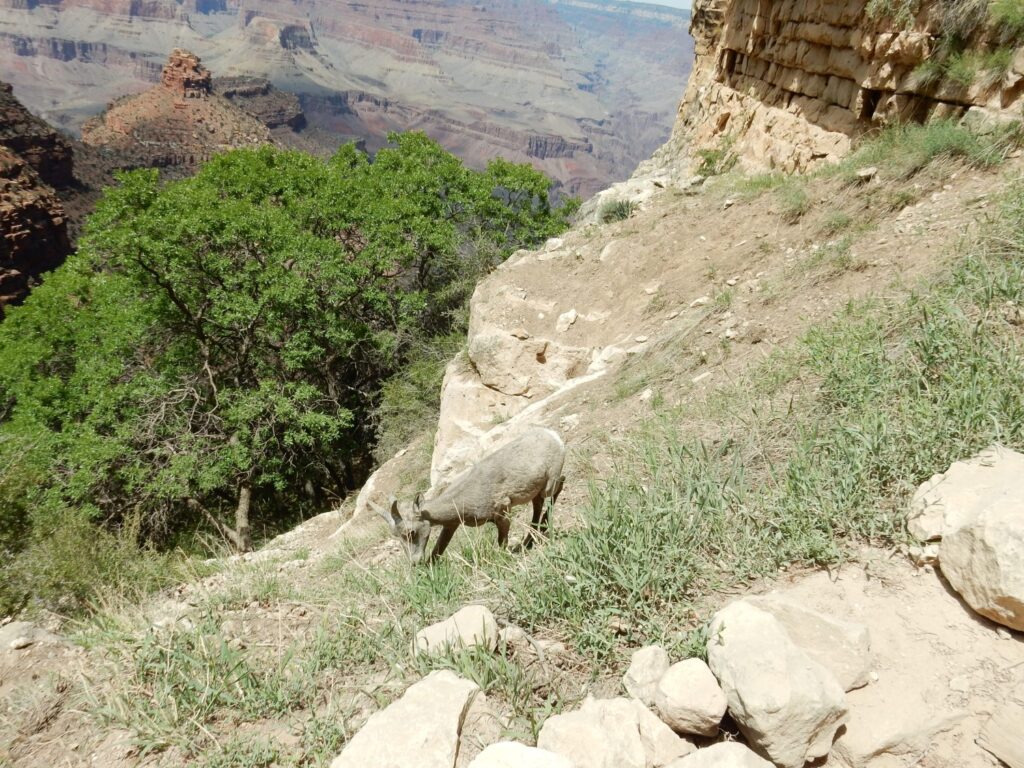

There are critters resting at the base of the Coconino cliff.

Oh … geology. The top section of the Hermit Shale.

The Hermit Shale is also Permian, around 275 million years old. In other words, it’s barely distinguishable in age from the overlying Coconino. The events that formed both must have occurred in quick succession. It’s all the more remarkable because, everywhere the top of the Hermit crops out, the contact is very sharp like this.

As we continue to descend, we get additional angles on the critters.

Beneath the Hermit Shale is the Supai Group.

The Supai Group finally gets us out of the Permian into the Pennsylvanian. Its beds are about 290 to 320 million years old, and are fluvial (river) deposits of mudstone and sandstone from rivers coming off the Uncompahgre Uplift to the northeast. This was the time of the Ancestral Rocky Mountains, produced by continental collision during the assembly of Pangaea.

One more critter shot.

And now we come to the sheer Coconino wall on the east side of the Bright Angel Fault. It’s pretty clear here that it has been thrown down a considerable distance along the fault.

At left, the more distant canyon wall shows the formations so far pretty nicely. Kaibab forming the rim; a slopt of Toroweap below that; another cliff of Coconino; a slope of Hermit Shale; and then ledgy red beds of the Supa Group.

Little critter.

The rodents along the trail are incredibly tame. Also incredibly fat. I suspect this actually helps keep the population from exploding — the plump little guys can’t waddle away from predators fast enough.

We reach 1.5 Mile Resthouse and take a short break. There is water — under rather high pressure; there’s a lot of hydraulic head in the pipes. Beyond are the sandstone and mudstone beds of the Supai Group..

We meet a trail volunteer, who tells us where to see some petroglyphs in the cliffs above.

Why, yes, those are reverse swastikas. The swastika was a symbol used by many cultures, before the Nazis kind of ruined it.

Thinly bedded sandstone.

Along the trail:

I don’t actually know what critter. It seemed to have three claws on each foot, though.

Little living critter.

They really are utterly fearless. At least around humans.

We reach Three Mile Resthouse. There is a nice little covered rest area where we can eat lunch. It has an emergency telephone, interestingly enough. The squirrels here are ludicrously tame; two stroll up to within inches of my hiking boots. Some of the birds here are nearly as unafraid of humans.

The resthouse rests on the top of the Redwall Limestone. I examine the lowest beds of the Supai Group, which appear to have fossil burrows in them.

Wildflowers.

The Redwall LImestone.

The trace of the Bright Angel Fault is very clear here. You see Redwall LImestone to the right, juxtaposed to Supai Group to the left.

It is the fault that made trail construction possible here, I suspect. The fault provides a path across the cliff-forming formations, by breaking them up along the fault.

The Redwall Limestone is Mississippian in age, around 340 million years. It records a time of relative stability, with sediments accumulating on a continental slope. It probably correlates with the Arroyo Penasco Group back home. The limestone is actually blush-gray; the red color is sediments coating the limestone that were washed down from the red beds above.

We take stock, and decide that our original plan to turn around here is still a good one. Gary does not want to wreck his feet and I do not want to blow out an artery. The switchbacks down the Redwall are fearsome, and going up is going to be harder than going down. Or so I expected; it turns out that going back up, while definitely tiring, will not be as hard as I thought. I still think sticking to six miles round trip was the wise choice.

View down on the way up.

At left, the Redwall, with Supai Group above and Muav Limestone below. The Muav is much older than the Redwall, being Cambrian in age, around 510 million years old. There are indications here that the Redwall was deposited on a very irregular erosional surface — not unusual with limestone, which tends to form rugged karst surfaces when it erodes.

Below the Muav, the greenish slopes are Bright Angel Shale, also Cambrian but around 520 million years old. Beneath this, just visible in the distance, are cliffs of the Tapeats Sandstone, early Cambrian in age (540 million years) and the rim of the innermost gorge of the canyon. Beyond are ancient metamorphic rock beds of the Vishnu Schist and other Proterozoic formations, around 1.8 billion years old. Would have been nice to see them close up, but see: 59 years old, wrecked feet, blown arteries.

Trace fossils?

The trail is very busy and we’ve met a lot of interesting people. Gary has a long conversation with a borough lawyer from Alaska who is here with her daughter. We also meet a couple of pretty young women, one of whom looks for all the world like The Girl with the Pearl Earring. I embarrass myself by crediting the painting to Rubens, then correct myself: Rembrandt.

Actually, it’s Vermeer.

Well, there were so many magnificently talented Dutch masters. A real flowering of culture at that time in the Low Countries.

Not just people and squirrels on the trail.

The last is slightly zoomed. Still incredible.

We reach the top, tired but pleased with ourselves. We briefly stop at a museum and book store and I get a book on Grand Canyon hiking trails that appears to have a pretty decent introduction to the geology. We then hurry south to Flagstaff, taking the scenic route through the San Francisco Mountains (U.S. 180). In Flagstaff we find a Korean barbeque; I try my first kimchee. (I know. At my age, about time.) It’s actually pretty good. The other dishes are very good as well.

Gary’s wife and daughter-in-law have actually bought kimchee pots and are planning to brew up a big batch. Gary mentions this to the waitress, and she is delighted.

Then south to Mormon Lake and our campsite at Dairy Springs. It is already dark when we arrive, and we quickly set up camp for the night.