Wanderlusting Colorado, day 3

Dawn at Sand Gulch Campground.

The cliff in the background is Ordovician in age, in the ballpark of 460 million years old. My map is not more detailed than that, but a good guess is that this is the Harding Sandstone. It’s apparently a very popular rock climbing area; the campers at the next campsite tell us they’re out for a weekend rock climber convention that apparently involves much beer and coffee, and they’ve come out a couple of days early to do some actual rock climbing. I can imagine that that vertical face is perfect for it. Gary even spots the glint of sunlight off some rock anchors on the cliff.

I take a morning walk along a forest road that we might drive later, which passes through Ordovician beds allegedly fossiliferous. To the west is a downthrown block of Fountain Formation.

Fountain Formation is Pennsylvanian to Permian in age, and like so many red bed formations of the western United States of that age, it is sediments eroded off the Ancestral Rocky Mountains. This makes it a cousin to the Cutler and Abo Formations in our neck of the woods and the Maroon Formation in central Colorado.

The red color indicates that the sediments were almost devoid of organic matter when deposited, which allowed the iron in the sediments to remain in the oxidized ferric state, as the mineral, hematite.

The geologic map shows that two faults converge just north of this hill. The hill is a block of younger rock that dropped between the faults and was preserved, with older rock all around it.

To the right, the mountains in shadow are underlain by granodiorite of the Routt plutonic suite. This is ancient rock, 1.69 billion years old, composed of rock slightly poorer in quartz than true granite. The Ordovician cliffs at center lie in an ancient valley eroded in the Precambrian rock.

It’s a gorgeous camp site. I chose it for its proximity to some interesting geology, but it turns out to be a good choice on its own merits.

I take the forest road north, but the Ordovician rock all seems to be sandstone, poor for preserving fossils. All I find are a few badly preserved bryozoans.

Bryozoans are distant relatives of molluscs, but living in colonies somewhat resembling corals. They are survivors; their lineage has been around from the Cambrian to the present day.

Some of the beds are striking, if devoid of good fossils.

My guess is that I’m looking at Manitou LImestone here, with Harding Sandstone above.

I turn round.

I’m a touch disappointed; I had hoped this area would be good for fossil collecting. I return to camp, getting another look at the Fountain Formation, now fully illuminated by the sun.

Gary is up and looking at his feet.

My back is feeling a bit better. I think I have more respect for our limits now. Ten miles in a day is getting to be too much.

That’s a nice piece of gneiss Gary has his feet on.

We head north on the forest road towards Cripple Creek. This is hard rock mining country.

That’s the Cripple Creek mine on the horizon.

Cripple Creek is a cluster of igneous intrusions in the surrounding Precambrian rock. These were emplaced around 28 million years ago, and were of a highly alkaline composition. Hydrothermal activity emplaced a considerable amount of gold and silver telluride in the area, an unusual ore that was not recognized for what it was until 1890. A gold rush followed, and some parts of the intrusive complex are still being actively mined.

Gary admires the vast tailings deposits.

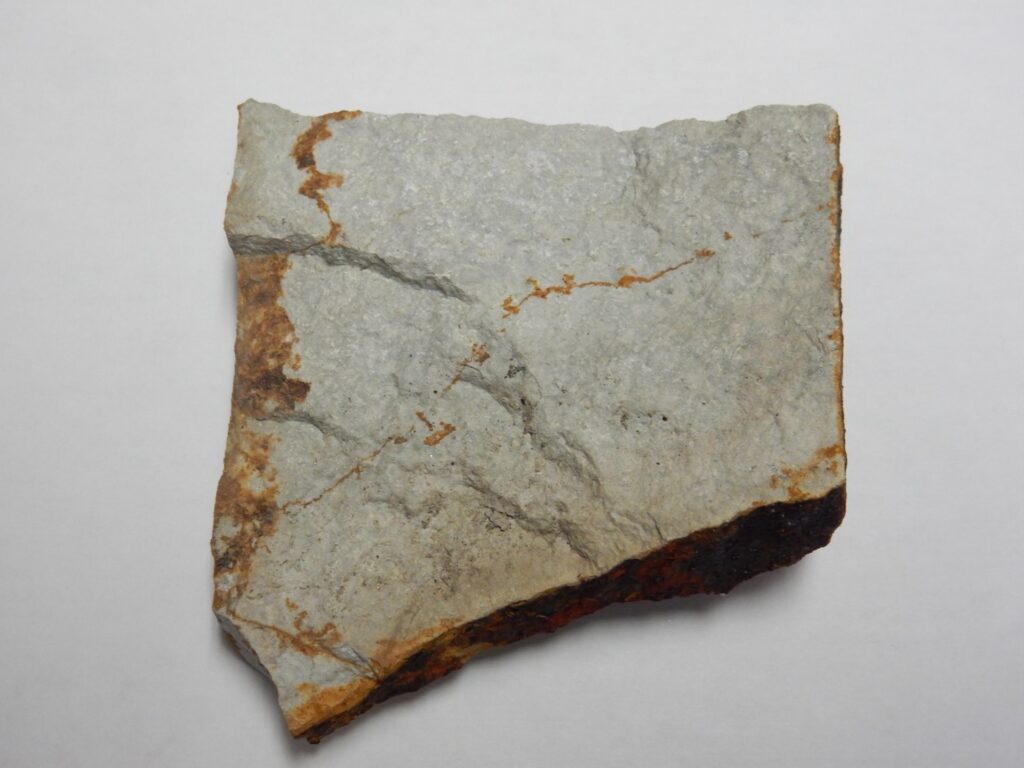

The road cut here is into a knob of phonolite, an uncommon type of igneous rock with a moderate silica content and a very high alkali metal oxide content.

Phonolite is dog-Greek for clinkstone, a name given to the rock by miners because of its tendency to ring when struck. The stuff did indeed clink underfoot, though the effect of hammering individual chunks was not as striking. (So to speak.) I grabbed a couple of samples for my collection.

Not much to look at, but it has an unusual mineral composition, rich in alkali feldspars, nepheline, and sodic amphiboles. These are all minerals rich in alkali metal oxides. Nepheline, in particular, is a feldspathoid, a mineral resembling feldspar but with a subtly different structure containing much less silica relative to sodium and potassium.

We are pressed for time, because we have an appointment at the Clare fossil quarry at noon. It’s a shame; I’d like to have explored the mines more. But this isn’t the ideal time of the year for it, since the mine tours have already closed for the season. For that matter, the Clare quarry is closed for the season, but the owner very kindly arranged to let us come by appointment.

We meet the owner, who checks us in and instructs us on how to hunt fossils.

We will not actually be working directly on the beds themselves.

This is the Florissant Formation, a lake shale formation around 34 million years old — close to the Eocene-Oligocene boundary. The underlying and surrounding rock is mostly Pikes Peak Batholith granite, but this area was a valley eroded in the granite. Volcanic eruptions to the west, associated with the Thirtyone Mile Caldera, blocked the valley and created a lake. Here volcanic ash accumulated from time to time, trapping organisms that are preserved mostly as carbon films between layers of the shale formed from the ash.

The quarry operators bulldoze large chunks of rock out of the formation, and visitors pay $15 an hour to split the shale using hand tools, looking for preserved organisms. The trick is finding a good chunk of shale and then splitting it along a dark layer, where organisms are most commonly found, using razor blades, putty knives, and hammers.

We go at it for two hours. We get considerable help from a quarry hand named Erin, who has worked at the quarry for years and is pretty good at finding the good stuff. Some of my finds:

Two leaf fossils are visible here. The one at left is magnificently preserved but, alas, the leaf literally peels off the rock and falls to pieces as it dries. The one at center is better preserved.

Close up of the one I lost.

I’m glad I got the photograph before it disintegrated.

This one (actually, the other side of the first) I was able to preserve.

Gary is enjoying himself.

Another good find. Actually found for me by Erin.

We head into Florissant, find a hardware store, and buy some transparent lacquer spray paint to better preserve our specimens. We then head back to our campsite via paved roads.

The peak at far left is Mount Pisgah, west of Cripple Creek. It’s a phonolite dome. The sharp peak just left of center is Little Pisgah Peak, if I’m reading the map right; the high ridge to its left is Grouse Mountain. Both are also phonolite. Phonolite seems to make up most of the high terrain around Cripple Creek.

View into wild country to the south.

Looking into the northern end of the Wet Mountains in the far distance.

We drive through Canon City and head north towards our camp site. The road cuts through a hogback in which the Dakota and Purgatoire Formations are exposed.

A hogback is a ridge formed when tilted sedimentary beds are eroded, and the most resistant beds stand out as one or more ridges.

A little further north:

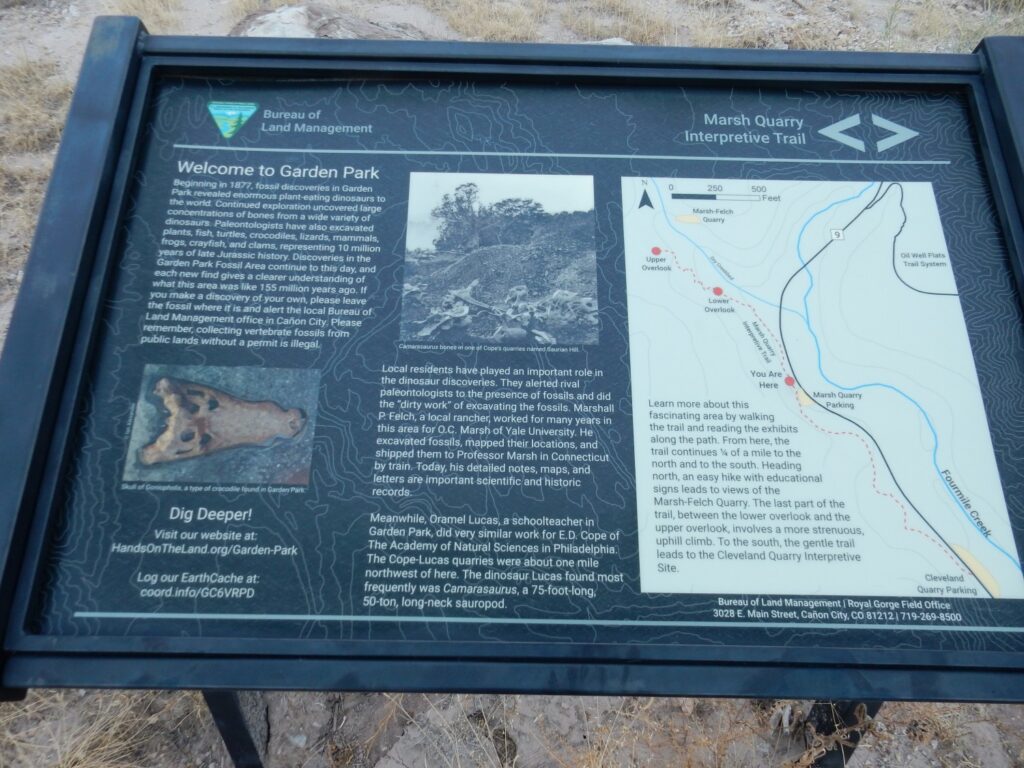

Othniel Charles Marsh was a professor of paleontology at Yale from 1866 to 1899. He is known for his bitter rivalry with Edward Drinker Cope, a self-taught field paleontologist and child prodigy who published his first scientific paper at age 19. It’s kind of a sad story: The two men initially seem to have been friends, but Marsh corrected Cope when the latter put a dinosaur skull on the wrong end of its spine, and things went downhill from there.

Commemorative plaque:

Assuming the plaque got it right, Marsh’s team found quite a selection of dinosaurs in this vicinity.

Cope had a rival team working in a quarry about a mile northwest of this location.

The quarry area.

Gary and I try to work out where the actual diggings were, and conclude that it was mostly the area below the trail visible at right. We hike some distance up the trail.

This outcrop looked interesting.

There appears to be burrows in the muddy layer.

Or possibly rhizoliths, plant root traces. I’ll go with burrows, either of crustaceans or of lungfish.

The quarry seen from the south.

The light is fading. We proceed to our camp, I cook up a steak dinner, we feast and retire for the night.

It turns out to be a windy night. The wind blows hard enough on my dome tent to bend the side down onto my feet. Fortunately I have the multiple blankets to keep me warm, but my feet get chilly enough that I make a mental note to break out my wool socks to wear to bed the next night.

That leaf you were able to save is pretty impressive!

Yes, it’s a very nice consolation for the lost one.