Thar’s gold in them thar wanderlust

Normally, after a long weekend with a long wanderlust, I’d be inclined to spend the next Saturday at home catching up on chores and giving myself a rest. But the weather was just gorgeous Thursday and Friday, and the forecast was for this to continue on Saturday. Then the monsoon would resume. Under the circumstances, I just couldn’t spend the day sitting at home.

So when I got home from work Friday, I skipped the usual unwinding period in front of my computer and got some weekend chores done, in advance. I told Cindy I really wanted to hike the next day, but that I’d try to be home early enough to get the rest of my chores done. She was pretty agreeable to this. And, to preempt any dark thoughts you may be thinking at this point, I was as good as my word.

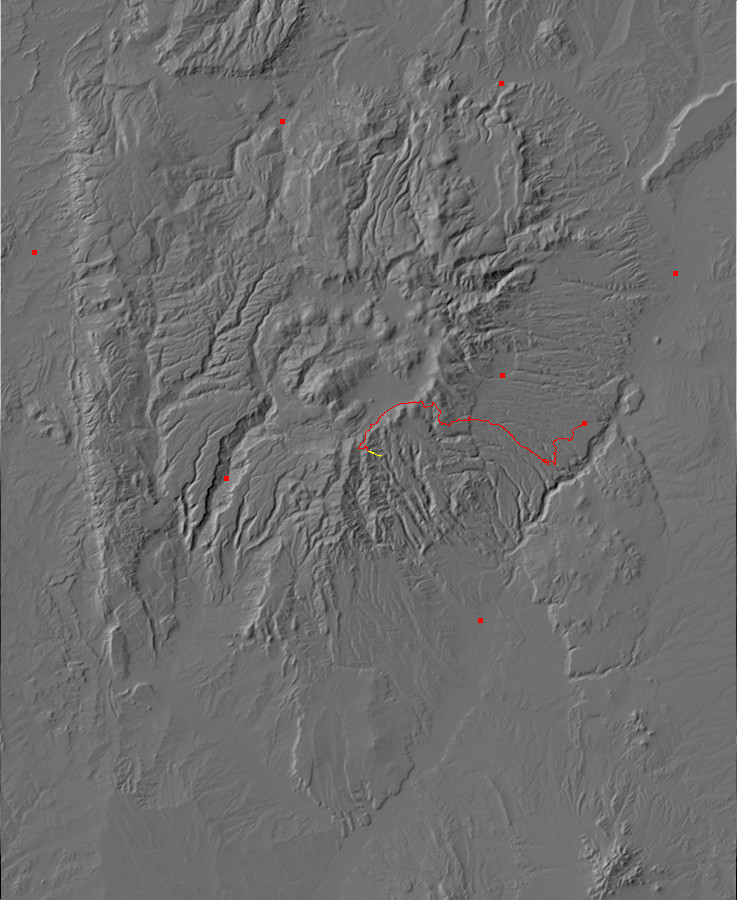

I had been planning for a long time to try to get to an outcropping of Bland monzonite. This is a formation important enough in the history of the Jemez that it really needs a place in the book, but it’s proven elusive. The main outcropping, which was mined for gold from about 1890 to 1930, is very difficult to get to; there are three roads in and all are completely washed out, plus there are some private enclaves I’d have to cross. There is another exposure west of Crager Ridge that is on National Forest land, but I have attempted every promising approach from north, east, or south and found that they all cross posted private land. After finding a good map of land jurisdictions, I settled on driving to the top of the ridge to the west (map) and then hiking down the crest of the ridge to the outcrop.

But the whole hike would be a bushwack over rough terrain, so I didn’t want to do it alone with a gimpy shoulder. Nor is it a hike to make in monsoon season, as the ridge is somewhat exposed. But here I was, with a shoulder that is feeling much better, and the weather just about perfect. Monzonite ho!

I got up at 6 (which is still sleeping in an hour, for me), breakfasted, packed, &c, and headed out. My route took me along State Road 4 into the Valles caldera, with a turn south onto the forest road leading to my trailhead.

Except that I mistook a private driveway for my forest road. This would not have mattered much, but I soon discovered that the entire length of the driveway was lined with automobiles of all makes and models. I have no idea what this was about, except that it had the feel of an automobile graveyard more than folks parking for some event. There was no easy way to turn around, either. I ended up backing a considerable distance to get to a spot where I could turn around and get back to State Road 4.

Fortunately, I hit the right exit for my forest road, 208, on my next attempt, and the gate was open. I started up into the south rim of the caldera, which here is mostly underlain by Paliza Canyon Formation andesite.

Much of the rock in the lower parts of canyons south of the rim is hydrothermally altered, from hot fluids “sweated” by magma cooling further underground. This particular outcrop is not much altered, except for some red stains of iron oxides. But a little further down the road, I came to andesite so altered that it was bleached white.

These images are worthy keeping in mind for later reference. I would be hiking into an area in which hydrothermal alteration is also present and can make rock identification uncertain.

I turned east and then south towards my trailhead, passing a striking outcrop of Bearhead Rhyolite along a fault zone.

Most of the southern Jemez is underlain by andesite of the Paliza Canyon Formation, which was erupted from around 13 to 7 million years ago with the peak at around 8 million years ago. Andesite is described as intermediate in its silica content. Some of the earlier flows were basalt (low in silica), while some late flows were dacite (higher in silica.) All of these rocks show geochemical signatures suggesting they were derived from the mantle, with the more silica-rich magmas being differentiated through crystallization and settling out of silica-poor minerals.

The Bearhead Rhyolite, which erupted mostly along faults in the southern Jemez, is around 6 to 7 million years old. It is similar to the older Canovas Canyon Formation (7 to 12 million years old) and has a geochemical signature suggesting it originated in the lower crust, where the rock was melted by more silica-poor magma that was too dense either to reach the surface or to mix with the silica-rich melted crust.

Ahead: The knoll from which my hike would start.

Yeah. The lighting is dreadful here. The knoll is not nearly as dreadful-looking in real life.

I found a perfect parking spot on the west side of the knoll and disembarked. The view to the southeast seemed worth a panorama.

The lighting is not great and the dead trees obscure enough of the view that this is not one for the book. Still, if the trees were alive, there would no view at all (and I might have gotten lost on this hike.) Forest fires are not all bad; destructive as they are (and the destruction can be pretty devastating), they renew the ecosystem and they expose the geology.

Alas, part of the renewing of the ecosystem is that the burned-over ground becomes thickly covered with shrubbery. With very sharp and numerous thorns. I would come back from this hike pretty badly scratched up.

The immediate area had numerous outcroppings of andesite.

Yeah, that’s not one for the book, either. However, I got a sample.

I began working my way around the north side of the knoll, where there seemed to be a faint game trail. It was a good spot for a panorama to the north.

In the middle distance in the first three frames is Aspen Ridge, with the road I came in on visible in the first frame. Aspen Ridge is north-south along most of its length, but turns east at its north end (second frame) to form part of the south rim of the caldera. Redondo Peak and Redondito peek above the rim in the second and third frames, and lower Valle Jaramillo and Cerros del Abrigo are visible over the rim at the boundary of the second and third frames. Beyond them, the north rim of the caldera is just visible. To their right is the top of Cerro del Medio and, on the distant skyline, Tschicoma Peak.

The mass of hills on the right of the panorama is Rabbit Mountain and the Del Norte dome. These are underlain by Cerro Toledo rhyolite, around 1.45 million years old, and are believed to be the southeast remnant of a large ring fracture dome of the Toledo caldera (1.65 million years ago) that foundered into the Valles caldera 1.21 million years ago. The identification of Rabbit Mountain as a Cerro Toledo ring dome remnant helped establish the current belief among geologists that the Toledo caldera roughly coincided with the later Valles caldera, rather than being located in the Toledo Embayment.

I turned a corner and saw what I took at first to be my ridge. Except it seemed to drop to an abyss at the end, rather than descending into Canyon del Medio, and it was aimed too far north.

I scratched my head, consulted my map, and finally decided this was a mere spur and I would have to circle the knoll further to get to where my route down started. Which turned out to be correct. It helped that my GPS (or, to be more correct, Robin Robert’s GPS on semipermanent loan) showed I was north of my target coordinates.

I descended the ridge to a very old forest road.

The road cuts through a Bearhead Rhyolite dike intruding Paliza Canyon Formation hornblende andesite. I had considered hiking in along this road, to save some bushwacking, but the distance was considerable.

I climbed the next knoll to the east, which turns out to be a source vent for Bearhead Rhyolite.

Off to the south was a curious-looking outcrop on Aspen Ridge.

Here, I think. That would put this in the center of a large outcropping of Bearhead Rhyolite, which looks about right.

Looking ahead to yet another knoll to climb. Notice the heavy brush. There was no way to avoid it, and I slowly accumulated scratches on this hike.

This knoll is underlain mostly by Paliza Canyon hornblende dacite, but with another Bearhead Rhyolite dike cutting across the top. I saw several white rock fragments marking the dike. There was also a nice view to the southeast, towards Cochiti.

That’s Cerro Picacho and Cerro Balitas at left in the middle distance. I believe that’s Bland Canyon just right of center.

And here‘s what looks very much like Peralta Tuff along the Bearhead Rhyolite dike cutting across the dome.

Or perhaps not. It’s just a little too massive for a tuff, notwithstanding what appears to be embedded bits of pumice.

Here‘s an unusually well-exposed contact between a Bearhead Rhyolite dike and the surrounding Paliza Canyon dacite.

You can see that the dark purplish dacite at the top of the photo gives way fairly abruptly to white rhyolite.

I was now approaching my destination, and began watching for any unusual rock that might be monzonite. This was complicated by the fact that I was not quite sure what I was looking for. Monzonite does not differ that much in composition from the andesites and dacites in the area; the chief distinction is probably textural, since monzonite is more coarsely crystalline. But here the rock would be more hypabyssal (formed at shallow depth underground) than really plutonic (formed at great depth underground) so the texture difference might be subtle. Plus, most of the Bland monzonite is more or less hydrothermally altered, and this sometimes extends to the rocks immediately around it. It is this hydrothermal activity that separated the gold from the monzonite and produced veins with traces of gold in the Bland area further south.

But this caught my eye on the west slope of the knoll, where my map showed a monzonite dike, I picked it up, and stuffed it in my pack.

It’s unlike any other rock in the area. As it turns out, this is almost certainly Bland monzonite. No better candidate ever turned up.

I got to the top of the knoll, where from my map I expected to see obvious outcrops of monzonite. All I saw was stuff that was not really different from the andesite I’d been seeing all along the trail.

I ate my snack orange while contemplating what to do next. I finally decided to circle around the north flank of the dome, where my map showed monzonite dikes radiating outwards, and just see what I could see.

I paused over these rocks for a few moments.

But they looked like andesite that had been subject to some mild hydrothermal alteration.

I scouted a little further east. There were one or two fragments similar to the sample I showed earlier.

Further on, and now there were substantial numbers of fragments of what I was coming to think was the monzonite.

I scouted around some more, and convinced myself that I was tracing out a thin dike of monzonite. Cool.

I paused for a photograph to the north.

Del Norte dome on the left, the Rabbit Mountain complex at center, and the east caldera rim to the right. The outcrops on the canyon rim just right of center are tent rocks of the Otowi Member, Bandelier Tuff.

I headed to the east side of the knoll.

That’s St. Peter’s Dome nicely framed by the trees.

From my map, it looked like I could continue on down the hill to an area of many monzonite dikes. On the other hand, it’s a steep hill and I already have a long climb back …

I hiked down just a little further. Here I spotted another interesting distant outcropping to the southeast. Here, I think.

This turns out to be Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, thrown down by a fault just to the west.

I found myself in a patch of El Cajete pumice shown on my geologic map.

El Cajete Pumice is a very young (in geologic terms), having been erupted perhaps 55,000 years ago from a vent just south of Redondo Peak. Little patches of it appear all over the southern Jemez. It can be distinguished from other pumices of the Jemez both for its youth (as shown by it being on top of everything else), its slightly more off-white color than most pumices, and the presence of visible flecks of biotite in the pumice. I didn’t closely examine a piece here; the color and location were enough.

Well, good. I decided to head back by way of the south side of the knoll, and see if I could pick up a monzonite dike the map showed here.

I noticed something: The pumice patch seemed to be particularly heavily infested with sunflowers.

This may be significant. The Ancestral Pueblo People who settled in this area seem to have preferred farming areas underlain by El Cajete pumice. It apparently made for easily tilled soil that held moisture and it may have supplied nutrients.

Hiking west now, I found a contact between brown, fine-grained, nondescript rock and what looked like coarsely porphyritic andesite.

This threw me into doubt. Could it be that I have found the dike, and one or both of these is the actual monzonite? And which?

I hiked a little further and was relieved to find:

Well, there’s the monzonite dike. It’s just a little further west than I expected from the geologic map. (Or my GPS has started giving readings biased to the west).

Look, I’m in no position to criticize the accuracy of a geologic map. I am, in fact, in awe of the amount of careful work that must go into producing a reasonably accurate detailed geologic map of an area of incredibly rugged terrain with considerable soil and vegetation cover. It’s incredibly impressive.

Looking at the map, I concluded that the earlier contact was between Paliza Canyon massive andesite and volcaniclastic beds.

I grabbed a big sample rock for my yard. It’s not much different than the sample I showed earlier, except for being even more coarsely grained. The rock has big phenocrysts of feldspar and a black mineral that is probably pyroxene. Pretty, in its way.

Further west still was the coolest outcropping of the day.

The photo doesn’t do this justice, so this is not one for the book. But the lower right side of the outcropping looks like monzonite, while he upper left looks like andesite. The stuff between looks like a partially fused mixture of andesite fragments and monzonite matrix, subsequently hydrothermally altered. Which is probably about right.

It occurred to me that, if there was gold ore anywhere on this hill, it would probably be here. But probably not: The gold-bearing zones further south are quartz veins, whereas there is no sign of silica alteration here. It’s just as well; stumbling across gold ore would have been awkward.

I began the long hike back, with a final look back at the monzonite-intruded knoll.

I found an outcropping in front of me in an area mapped as Paliza Canyon hornblende dacite

so pretty that I took a sample.

At first glance, this looks little different than the andesite further up the ridge. On closer examination, however, the plagioclase phenocrysts (white patches) are seen to have a distinct lath shape (they are euhedral) and they form clumps. Furthermore, the clumps incorporate a few black crystals of hornblende.

Looking back at the hornblende dacite knoll.

Wildflowers.

Oenothera drumondii, perhaps?

Looking back at the Bearhead Rhyolite knoll.

I found myself back at the old forest road.

Gosh, that looked like easier hiking than the ridge above me; I was tired by now, to the point of occasionally stumbling. I recalled seeing that the road came close to where I had parked my car, though I’d have a short but steep climb up. Sounded better than fighting through so much bramble.

The road turned out to have numerous dead trees across it, but still not too bad. But then I made the mistake of starting my climb up too soon.

(Well, maybe not such a mistake. Looking at the relief map, the route I intended was even steeper and more rugged than the one I mistakenly took.)

The climb up the hill turned into a nightmare of fighting past bramble and seeking routes through aspen. (The aspen seedlings were no problem to push past.) I was soon spotted with blood from deep scratches; I even scratched the top of my head badly. After a seeming eternity, I saw the top of the hill ahead, and heaved myself up expecting to find myself at the edge of the forest road …

Shucks and other comments. I realized now that I had started my climb up too soon, and there was the forest road, way way away.

I worked my way around the final knoll, which was covered with andesite scree.

I had a last burst of ambition: I bet I could get a truly spectacular panorama from the top of this knoll.

I started working my way up. And was that a dike ahead?

No, it was not, as I discovered when I got closer. Just an exposure of thinly bedded andesite. And the top? Not from this side; not with a shoulder still recovering from surgery; not when I’m this tired. Not safe.

And the Wandermobile was sitting invitingly not far ahead.

I climbed back down to the car.

You know? It was only around 1:00. I ate my lunch, then considered where the forest road I was on might continue to. No, I promised to get back early; Will. Resist. Temptation. To. Reconnoiter.

I’m glad I did. When I got home and checked Google Maps, I found that it essentially went nowhere.

But on the way out, I passed near an area marked as hydrothermal breccia on my map. This won’t take long.

So there are broken rocks, and they look hydrothermally altered, particularly in comparison with a neighboring area:

I’m not sure I actually found the hydrothermal breccia, whose description in the map report is a bit more dramatic. But this is more or less the area, and probably worth scouting more in the future.

You may be thinking: Was it really worth fighting through brambles to see a few poor exposures of monzonite? My verdict: I was glad I came; I would never do it again.

So why not go to the really good exposures down south? I’ve mentioned there are only three roads in, and they’re all in rotten shape. The Del Norte road is no road at all now; it’s become a deeply eroded ravine, parts of which are on posted private land. The old forest road halfway through my hike turns out to head to Bland, but it’s obviously in terrible shape as well, and it also crosses at least three private enclaves that may be posted. That leaves the Cochiti Highway from the south; it’s not in as terrible of shape, it’s more level ground most of the way, and the jurisdiction map shows that it’s fairly clear of private enclaves.

Or maybe not. Last time I drove past the turnoff to Bland, there was a locked gate with signs bearing variations on “We don’t want you here.” I sense a jurisdictional dispute between the state, the federal government, Cochiti pueblo, and private landholders in the mine area. (I can’t imagine why they’d argue over a an area that once produced gold and could do so again in the future.) I’m not sure I want to put my foot in that. So I’ll have to settle, at least for now, with having bushwacked down a brambly ridge to a few poorly exposed dikes of the monzonite, well north of the veins that were productive of gold ore.

On the drive out, I stopped for a photograph down Peralta Canyon.

The ridge on the skyline is Peralta Ridge, with radio towers. The canyon bottom is private land (you can see a cabin) but the forest road bypasses it. However, I haven’t seen anything on the geologic map that compels me to want to wander down that way. About the only thing unusual about the canyon is traces of Bandelier Tuff on the canyon walls, showing that Peralta Canyon was already a paleocanyon 1.6 million years ago down which some pyroclastic flows were channeled. … Huh. Maybe that’s interesting enough that I will explore the canyon more sometime.

As I drove along State Road 4 in Valle Grande, I found it such a beautiful day for photographing that I took four more photos of features I’ve seen many times before.

Cerros del Abrigo, north of the Valle Grande, with the north caldera rim behind (seen from here):

Cerro del Medio, showing the rugged exposures of rhyolite on its southeast face:

This shows just how steep a rhyolite flow can become (a high-aspect flow) due to the extremely high viscosity of rhyolite magma.

The Toledo embayment (from here):

Cerro del Medio to the left, Pajarito Mountain in the caldera east rim to the right. The photo is centered on Shell Mountain, which I want to see much closer up someday. (The topography seems interesting, but it would be a very long and difficult hike in.)

Finally, Cerros de Trasquilar and the caldera north rim.

And home.

Where I found Cindy headed to the doctor with Kira, who had an infected and very painful hangnail. I was hot, tired, and covered with increasingly painful scratches; I sat down for some diet root beer over ice while moving these photos onto my computer. I was adequately recovered by the time Cindy and Kira got back to clean the car, mow the lawn, straighten up the kitchen a bit, and replace the ballcock of the toilet in the main bathroom. Turns out the last one I installed was too short; this one looked like it would never fit in the toilet tank, but it just barely did — I expect by design — and the toilet is working much better. Toilets do not do well flushing from a tank that is not fully filled to its design level.

Kira was in something like agony at this point, because the lidocaine the doctor had used to numb her toe while he cleaned it out had worn off and her fibromyalgia gives her a very low pain threshold. I ran back to the store and got some lidocaine burn cream; this seemed to help.

So I tried a little on my own scratches. Did not help much. But they’ve stopped hurting today and I’ll be ready for work tomorrow. Well, as much as I ever am; it’s not a bad job, it pays very well, and at times it’s very interesting, but it’s still a job.

I guess I’m saying that a bad day in the mountains is still better than most days at the office. Quelle surprise, no?