Wanderlusting the Mitchell Trail a bit more thoroughly

My visit to the Mitchell Trail last week was mostly a case of getting my daily exercise at a different spot from usual, for a change of pace. There’s not that much variety of geology; it’s all one giant flow of the Tschicoma Formation.

But the area was so beautiful that I figured it deserved more than a quick hour of hiking, so Friday I devoted a full afternoon to hiking the trail.

At the trailhead.

I discussed the geology pretty thoroughly in my last post, so I’ll go with briefer descriptions here. The hills in the background are part of Guaje Ridge, which in turn is a spur of the Sierra de los Valles, the mountains that form the western backdrop to the town of Los Alamos. The entire Sierra de los Valles is underlain by Tschicoma Formation, which is dacite (a high-silica variety of volcanic rock) erupted in two pulses, at 5 and 3 million years ago. Almost everything we’ll be seeing today will be the Rendija Canyon Member of the Tshicoma Formation, which is dacite of the older pulse.

However, the lower part of the trail crosses Bandelier Tuff that was erupted into upper Rendija Canyon about 1.256 million years ago. Unlike the Tschicoma Formation, whose eruptio was effusive (the magma came out of the ground more or less as fluid lava, albeit extremely viscous fluid lava), the Bandelier Tuff was erupted explosively, in a giant caldera eruption that produced the Valles Caldera on the other side of the Sierra de los Valles. The magma was broken up into a mixture of tiny shards of volcanic glass and red-hot gases, which was heavier than air and flowed like a liquid for miles in all directions. It then settled to the surface and cooled into a soft, porous rock called tuff. The Bandelier Tuff records at least three such eruptions, and the tuff beds from the Valles eruption (which was the most recent) are assigned to the Tsherige Member of the Bandelier Tuff.

Here is some.

The tuff is soft enough that a few decades of hikers have worn the trail deeply into the tuff.

The trail climbs into upper Rendija Canyon.

It’s late fall, of course, so the broadleaf bushes and trees have shed their foliage. But this area is barren in part because it was burned over in May 2000 by the disastrous Cerro Grande fire, and what was left was burned over a second time by the 2011 Las Conchas Fire. We were living in Los Alamos by 2011 and have dark memories of evacuating our kids to Albuquerque for the duration. Fortunately, the fire did not get close to our house in White Rock, but the earlier fire had burned my brother-in-law’s house to the ground.

A prominent knob on Guaje Ridge.

Another knob to the southeast.

Dacite lava is so highly viscous that it tends to form high flows, plugs, and knobs like this. The flow likely was covered with a veneer of solid dacite boulders, but these were quickly eroded away to form the Puye Formation to the east. The flows were left denuded (yes, that’s a geologic term) by this erosion process, so that what we now see was the liquid interior of the flow that cooled into solid rock.

Rock like this.

The rock is full of large crystals (phenocrysts) of feldspar, likely potassium feldspar. The dark color of the rest of the rock suggests it is glassy. It’s possible almost all the dacite was originally dark glass like this, but has since devitrified to form the reddish rock predominant in this area.

Up ahead is the Guaje Window. I get a telephoto shot.

This is a popular hiking destination, though the trail is steep and requires some scrambling. I wrenched my knee pretty badly the last time I climbed to it, eight years ago. I don’t plan to hike to it today, but I have tentative plans to take some friends to it next week during the holiday break.

Pulling the view back a bit.

Further up the canyon is a rare knob with horizontal bedding.

I’m not sure why, in this one spot, the dacite is horizontally bedded, when it’s vertically jointed almost everywhere else. The geologic map offers no clues.

The Mitchell Trail has a couple of strands; I’ve been hiking the higher one, which does not lead to the Guaje window spur trail. Here the two strands rejoin in the middle of a gully.

The trait switches up Guaje Ridge from here.

Halfway up, I see a beautiful sight to the south.

(click for a high resolution version, as you can do with most images at this site)

My childhood memories of the Sierra de los Valles are of them blanketed in a beautiful dense green pine forest. The forest fires devastated that. But here, backlit by the sun, is the conifer forest returning to the area, starting with the less parched ground on the north side of ridges and hills.

A solid outcrop of dacite along the trail.

This solidified deep in the flow, and so forms a solid fine-grained rock. If you click for full resolution, you can see that it noetheless has the characteristic large white feldspar crystals.

The dacite forms slopes of grus-like debris.

True grus forms from weathering and fragmentation of granite. The stuff here weathered from much finer-grained dacite, but the chemical composition is quite similar. I suppose I should be nervous; it hasn’t been that many years since I broke an ankle slipping on grus.

The trail is steep and I’m almost 60. I pause periodically to check my pulse; it’s pushing towards 150 so I need to slow down. However, I feel pretty good, considering.

The townsite and Omega Bridge.

The canyon crossed by the bridge is Los Alamos Canyon, which separates the main Los Alamos National Laboratory site (on the south) from the main town site (on the north). The bridge is decades old, but just got a face lift this fall. Presumably it’s holding up well structurally. It’s actually quite a beautiful bridge seen from below.

Pulling back for a panorama.

Lots of ridge still above me.

Impressive that this all appears to be one massive flow from a vent somewhere to the west. Though it’s not impossible it erupted in a series of pulses, there’s no sign of erosional surfaces between separate flows.

More dacite in the trail.

This outcrop is heavily flow banded, meaning that it was slowly moving while on the verge of solidifying. There are outcrops like this here and there for miles along the ridge.

I have been climbing up a kind of sub-spur of Guaje Ridge, and now reach its crest.

A little further up the trail is some rock art.

Clearly modern, and I have no idea what its significance is supposed to be.

The trail curves around a kind of shallow amphitheater to the west. The view opens up to the east.

In the far distance is Black Mesa. It takes a few shots with the deep telephoto to get a well centered image.

Four groups of rock are visible here. In the foreground, all the darker stuff is dacite of the Tschicoma Formation. A little further east are light pink mesas of Bandelier Tuff. At center is Round Mesa, also known as Black Mesa (though there are two Black Mesas in the Espanola valley alone), composed of Cerros del Rio Basalt around 2.5 million years old. In the far distance are badlands eroded in the Santa Fe Group, sediments that accumulated in the Rio Grande Rift. The Rio Grande itself is marked by green vegetation just this side of Black Mesa (and difficult to pick out here, with the leaves fallen.)

More dacite.

I stop for lunch, then take a few panoramas and deep shots.

At center is the Barranca Mesa neighborhood of Los Alamos.

At left is the wild country northeast of Los Alamos.

The trail approaches the crest of Guaje Ridge, where the rocks for fantastic shapes.

One more look at the Los Alamos town site.

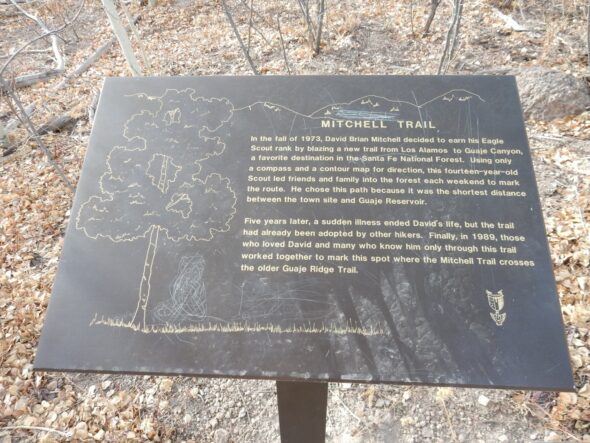

Atop the ridge, the Mitchell Trail crosses the Guaje Ridge Trail, and there is a plaque.

This was more or less the objective of my hike. But I’ve made good time, and I have three choices: Turn around now anyway; continue on the Mitchell Trail; or return via the Guaje Ridge trail. The latter will make for a long hike but it will mostly be downhill. Well, my left foot is hurting slightly; it felt like there was a rock in my shoe but I couldn’t find it. I decide to press ahead just a little further on the Mitchell Trail, enough to get a good view into upper Guaje Canyon.

Right, not left.

It’s worth the extra hikage.

We are looking here into upper Guaje Canyon. Most of the rock here is Tschicoma Formation, but the distant hills right of center are Santa Clara Mountains, underlain by much older rock of the Lobato Formation (around 9 million years old).

The outcrop down the canyon catches my eye.

The geologic map confirms this. In fact, the entire cliff here, plus the plateau beyond, is Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff.

The rugged terrain across the canyon to the left is the Caballo Mountain Member of the Tschicoma Formation. It is part of the younger pulse at around 3 million years ago. More precisely, the uppermost part of this member has been dated at 3.03 million years old.

That topmost part is the top of Caballo Mountain.

I’ve never been to the top, but Cindy has. The easiest access is from the north, but that’s Santa Clara Pueblo land; Cindy went as a guest of a member of the pueblo, a woman she worked with.

A little further, and I can see clear up Guaje Canyon.

One more of Caballo Peak

I am not quite halfway through my time budget, so I decide to turn back here. On the way back, a deep telephoto shot to the east:

The mesas are Bandelier Tuff, but the gray beds just below center, further down Guaje Canyon, are Puye Formation beds. I got a much closer look at these earlier in the year.

I come back into view of Los Alamos.

I take the other branch of the lower trail. The spur to Guaje Window is obvious.

Further down canyon, I hear voices. Turns out someone has climbed the knob above me.

I decide on one more side trip, to look at the bank cut for the big water tank here.

I know: Wut? It turns out the geology here is Bandelier Tuff overlain by what is called the Golf Course Alluvium, which is material washed across the surface by a stream network before all the steep canyons of the Pajarito Plateau were cut. IN some places, this is quite extensive, such as (cough cough) the Los Alamos golf course. Here the top stuff is clearly alluvium, and the bottom is probably Bandelier Tuff, but from a distance it’s hard to tell where the contact is. And the are is fenced off so that I can’t get a closer look. Shucks.

But I’m tired and ready to go home, so I hike back to my car, picking up a few groceries on the way home.

The next is mostly for family and close friends and may be TMI for other visitors. Don’t be ashamed to quit here.

The minor stuff first: After I got back from the hike, I checked out my foot a bit more thoroughly where it felt like I had a rock in my shoe. Sure enough, it looks like I’ve grown a couple of plantar warts on the side of my foot. It’s a minor problem but I may have my doctor take a look, and attempt removal. They’re likely to be a continuing nuisance on hikes if I don’t.

More serious: I had a bit of a scare a couple months ago, and the short of it is that I had a thorough cardio workup last month. I got the full results this week. My heart looks great, with normal valves (for my age) and good blood supply everywhere … except my right heart is mildly enlarged.

There’s no obvious reason for it. My valves all look good and the blood pressure in my pulmonary artery is normal for my age and this altitude. My cardiologist is encouraging me to continue vigorous exercise, but meanwhile I’m going in for a sleep study. A plausible candidate is obstructive sleep apnea. When I told Cindy, she kind of rolled her eyes and reminded me I snore like a horse. (Do horses really snore?) So we’ll see. Fingers crossed.