Wanderlusting Potrillo Canyon

The weather continues to be mild and dry, so I decided a good way to get some exercise would be to hike the Potrillo Canyon Trail. The trail head is off of State Road 4 (map), within easy walking distance of my home, and the other end of the trail gives yet another view of White Rock Canyon. And it’s hard to get tired of White Rock Canyon.

Potrillo Canyon itself is a shallow canyon that more or less constitutes the southern boundary of the town of White Rock. It is underlain primarily by Cerros del Rio tholeiitic olivine basalt covered with a varying thickness of colluvium, and flanked by mesas of Bandelier Tuff.

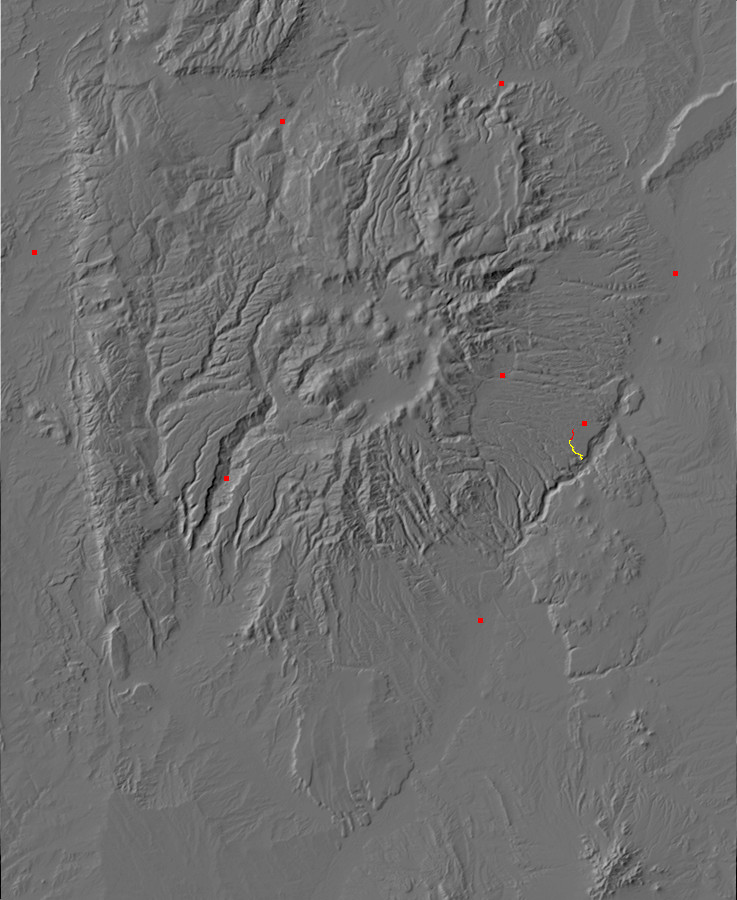

The Cerros del Rio is the broad volcanic plateau on the east side of White Rock Canyon, which was erupted between 5 million and 1.2 million years ago, with a peak around 3 million years ago. The lava flows from the Cerros del Rio extend well west of the Rio Grande, but are usually buried under Bandelier Tuff and colluvium. I wrote about the Bandelier Tuff in my last post.

Okay, some terminology. Tholeiitic olivine basalt: This is volcanic rock that is quite low in silica, so that it contains olivine, an iron-magnesium silicate mineral, rather than quartz. Tholeiitic basalt is also relatively rich in iron, due to forming in a low-oxygen environment. The high iron content makes for a very dark rock. The magma this rock formed from came more or less straight from the earth’s upper mantle.

Colluvium: This is basically the hifalutin geological term for “dirt.” More or less: Colluvium is dirt that fell, blew, or washed down from nearby high ground. In the Los Alamos area, that almost always means from mesas of Bandelier Tuff. Geologists don’t find it all that interesting, but when it is thick enough to conceal whatever more interesting rock is beneath, they have no choice but to put in on their geologic maps.

The hike down the canyon was pleasant, but unremarkable enough that I didn’t stop for pictures. (I was out for exercise, after all, and wanted to keep up the pace.) However, towards the end of the trail, Potrillo Canyon merges with the much deeper Water Canyon (map), which lies to its south. Water Canyon is large enough to have cut through much of the Cerros del Rio basalts. Here I paused for a panorama (map).

At far left and far right are the basalt cliffs that mark the sudden drop from the relatively shallow Potrillo Canyon into the much deeper Water Canyon. Water Canyon descends from the Pajarito Plateau in the third frame and continues to its confluence with White Rock Canyon in the first frame. Part of the east rim of White Rock Canyon is visible on the skyline in the first frame, with Montoso Peak on the skyline.

The feature of greatest geological interest is probably the large outcropping of light pink Bandelier Tuff in the south wall of Water Canyon in the second frame. I perused this for some time and concluded that the outcropping has not slumped down the canyon wall; it was this thick when deposited 1.21 million years ago. Since older Cerros del Rio basalt and underlying Santa Fe Group sediments form the rest of the canyon wall, this shows that the Bandelier Tuff filled a deep ancestral Water Canyon when it was erupted, and erosion has since re-cut the canyon, leaving this remnant on the canyon walls.

The San Miguel Mountains (map) form the distant skyline in the third frame, and the Sierra de los Valles west of Los Alamos (map) form the distant skyline in the last two frames.

I continued to the end of the trail (map), where is a magnificent overlook into White Rock Canyon.

All kinds of interesting stuff here. The light pink outcrops in the second frame are more Bandelier Tuff, which likely flowed down the ancestral Water Canyon and crossed the ancestral White Rock Canyon to form the beds here. These are the furthest southeasterly beds of the Bandelier Tuff, and they are likely the “white rock” from which White Rock Canyon gets its name.

There is a kind of natural amphitheater in the fourth frame, formed by landslides. This exposes a great thickness of Cerros del Rio lava flows lying atop beds of phreatomagmatic cinder. Phreatomagmatic cinder forms when lava erupts into a shallow lake or water-saturated ground and steam explosions blow the lava and country rock into tiny fragments. The buttress to the left of this natural amphitheater, on the boundary of the third and fourth frame, is identified on the geologic map as a hypabyssal plug of basalt, which cooled at some depth below ground. It looks to me like this is a paleocanyon that was filled to a great depth with lava.

Near the boundary of the final two frames, some distance down the canyon, is a conical hill of basaltic andesite at the mouth of Ancho Canyon. This is likely an erosional remnant of a natural dam that once blocked the canyon at this point, where it is particularly narrow. This dam produced a large lake, which geologists have named Lake Culebra, filling the entire Espanola Valley to the north. Lake bed deposits are scattered across the mesas to the west of the Rio Grande, north of Pueblo Canyon and the main highway to Los Alamos.

I retraced my route and headed home, tired but satisfied. And my shoulder was hurting: As I may have mentioned before, it seems I tore my left rotator cuff last spring, and it isn’t healing on its own. I’m getting an MRI tomorrow and we’ll see. I may not be able to do as much hiking this summer as I would like. Wish me luck.

Classic Kently.

How did the MRI go?

Painful. They shoved my shoulder in some kind of brace, which hurt; then I got to lie there with my shoulder in this brace inside the MRI for thirty minutes, which hurt worse.

I don’t know what it told them. I won’t find out until Thursday. I’m hoping they’ll have some kind of clever physical therapy that will strengthen my shoulder, but I’m expecting they’ll want to do surgery.