A sedimental journey, day 2

It does not quite rain during the night, but it seems to have been thinking about it. The forecast is for crummy weather today, which is regrettable considering that Capitol Reef National Monument, our destination for the day, deserves sunny weather.

Be that as it may, we breakfast on cold cereal, bacon, and eggs (having discovered we have no spatula for pancakes, and finding a hand trowel adequate only for bacon and scrambled eggs) and break camp.

I do not realize it at the time but, judging from the geologic map, we are camping on a surface of the Organ Rock Shale. This has the look of a fluvial sandstone, and it’s not a prominent formation; it tends to erode easily off the much more prominent underlying Cedar Mesa Sandstone. It’s also not immediately distinguishable from the overlying Moenkopi Formation, which is chocolate brown tidal flat deposits.

We were unable to find a spot at the Natural Bridges National Monument campsite last night, and so found a spur off a road on BLM land. We were thus engaged in what the agencies call “dispersed camping”, which means small groups camping on unprepared sites on public land for free. It’s legal most places on BLM and National Forest land, but there are local exceptions. We knew of none here.

The tent further down the spur turns out to be occupied by a couple of women. Gary strikes up a conversation. One is an older American and the other is from New Zealand. She appears to be part Maori and has a delightful educated British accent. I mention that I had been in Christchurch in 2008 and had admired the cathedral, just north of my hotel, which was severely damaged in the 2011 earthquake. The older women mentions that her son is a physicist who is looking for more interesting work; Gary brings up explosives research at LANL, and much bad punnage follows. (“I’t s a blast.” “He’ll get a charge out of it.”) The New Zealand lady winces.

We drive into the main part of the park, which is a plateau of Cedar Mesa Sandstone deeply carved by rivers.

The Cedar Mesa Sandstone was laid down around 270 million years ago, during the Permian. At this time, the west coast of North America ran north-south through Utah, roughly along what is now the mountainous spine of the state. The Cedar Mesa Sandstone was laid down as immense dune fields running inland from the sea.

Some more looks.

The pitted surface is likely a purely erosional feature.

The mesas in the background expose the other prominent rock units of the Natural Bridges National Monument area. The red slopes are Organ Rock Formation at the base (poorly exposed here), around 260 million years old. The Organ Rock Shale is part of the Cutler Group, corresponding with the Arroyo del Agua, Canon del Cobre, and Abo formations back home. It’s a floodplain deposit from when the sea withdrew further west and a river system developed over the area. Above this is the Moenkopi Formation, around 240 million years old, which is less river floodplain and more tidal flats. The mesa is capped with the lowermost resistant bed of the Chinle Formation, the Shinarump Conglomerate, which is quite prominent back home (and is there promoted to formation status.)

As with most images at this site, you can click to get a full resolution of the image. You can see that the Cedar Mesa is a massive sandstone, one indication that it was laid down as a dune field. Fluvial sandstones tend to be more thinly bedded and to include mudstone and siltstone from the flood plain.

We drive on to Sipapu Bridge overlook.

Natural bridges form when a meander of a river cutting down into hard rock cuts itself off to form an oxbow. The new course of the river is under the bridge and the oxbow is “stranded” at a higher level as the river continues to cut down. You can see part of the oxbow at left here; there will be better pictures in a moment. A natural bridge is distinguished from an arch, which is formed by wind erosion.

We drive on to the trail head, load up gear, hit the “heading out” button on the SPOT, and start down the trail.

It’s slickrock much of the way. In some portions, ladders are required.

Notice the cross bedding. Thick beds (which are nearly horizontal) are composed of sets of smaller beds laid at an angle, which can change abruptly from one thick bed to the next. The smaller beds likely formed on the lee side of dunes, which were then saturated by groundwater as the area subsided. The surface was planed off at the groundwater level by a new set of dunes, which in turn were preserved by further subsidence and saturation. This implies episodic subsidence. Geologists are increasingly aware of the importance of rare events — the thousand-year flood, the thousand-year storm, the rare earthquake — in the rock record.

We hike above the stranded oxbow.

The bridge is hidden behind the knoll at center left.

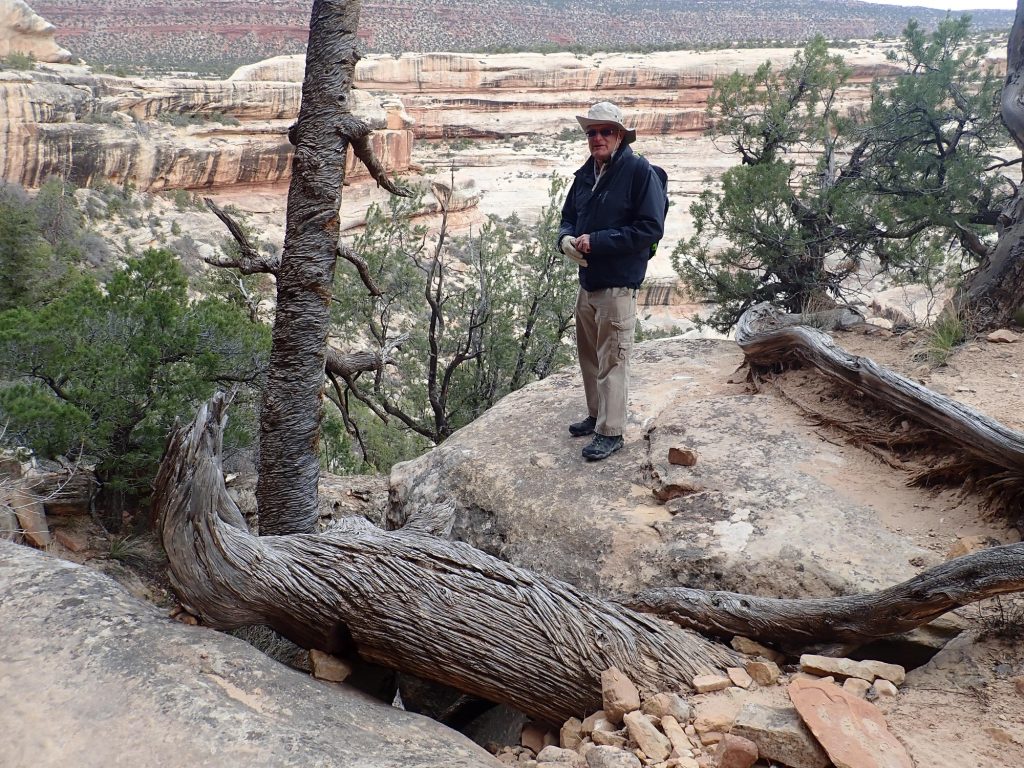

This dead tree looks distinctly crossbedded.

Not sure how old this is. One supposes it is an old Native American structure.

We hike round back into view of the bridge.

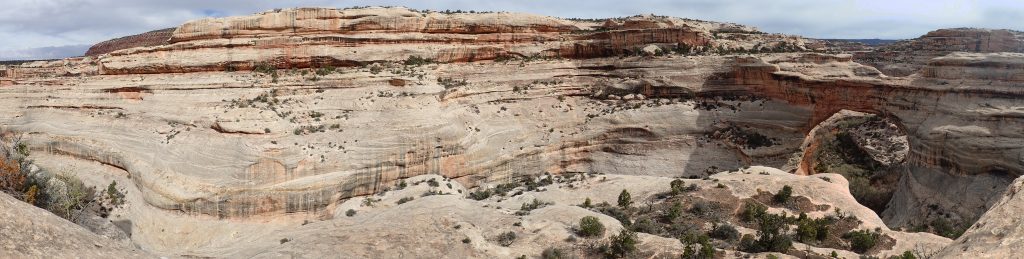

Panorama:

There are what look like human carvings in a rock nearby.

Not quite like any petroglyphs I’ve seen before.

The ledge we’re standing on was formed by a less resistant layer in the Cedar Mesa Formation.

I have an excellent book on the geology of Utah parks and monuments, and it speaks of a red mudstone facies that is distinct from the white sandstone facies that makes up most of the Cedar Mesa Formation. A facies is a particular rock type within a formation that represents a local depositional environment, but is not extensive enough to be mapped as a distinct member of the formation. This facies is mudstone and sandstone, rich in mica flakes, with occasional burrows and root casts, that is interpreted as flood deposits left in isolated interdune ponds. The process has been observed in Peru, in the altiplano region, in modern times.

Spectacular crossbedding in the east buttress of the bridge.

A scramble down a steep slope and a section of slickrock puts us finally beneath the bridge.

I note that this is poisonous rock. Gary is puzzled. I explain: One drop would kill us both.

We rest for a few minutes, eating snacks and guzzling fluids. Another hiker sloshes by; he is taking the entire loop trail that passes all three bridges. This requires some shallow wading in the river, which has significant water in it this time of year.

Starting back up, Gary explores the oxbow.

It is choked with boulders and shrubs, and we find a better view from above.

At one point, Gary suggests we try scrambling to the top of the bridge.

“No.”

I’m probably a lot less fun since I broke my ankle hiking.

We climb back to the top and drive on to Kachina Bridge overlook

and Owachomo Bridge overlook.

The hike to Owachomo Bridge is not far. We consider, then decide the time will be better spent at Capitol Reef.

On the way out: The Bear’s Ears.

Gary shares my view that the vast amount of land originally designated as Bear’s Ears National Monument grossly exceeded the statutory language of the Antiquities Act, which calls for the President to designate the minimum land necessary to protect the antiquity when proclaiming a national monument. Your mileage may vary.

The Ears are fins of the Wingate Sandstone, another massive dune field sandstone from the beginning of Jurassic time, about 200 million years ago.

The Cheesebox.

This landmark in Fry Canyon is carved out of the Moenkopi Formation. This formation will dominate the rest of our drive to Hite, where we will cross the Colorado River.

Moss Back Butte away to the southeast.

This feature gives its name to the Moss Back Member of the Chinle Formation.

We see a knoll ahead with a dirt road. Gary and I have the same impulse, and we drive to the top, finding a family from Spain there with their rental car. “Just like Spain”, Gary declares, getting a smile from the father.

The knoll is cut in the Organ Rock Formation, while the light areas in the valley are the upper surface of the Cedar Mesa Formation. The mesas are all Moenkopi Formation capped with the resistant lower bed of the Chinle Formation. In the distance, the weather is deteriorating over the Henry Mountains, which are laccoliths formed by great quantities of magma injected into the upper crust. This was part of a wave of igneous activity across the West 25 million years ago, thought to be caused by the subducted Farallon Plate disintegrating and sinking into the mantle.

We cross the Colorado and stop for lunch at the overlook near Hite.

As with the last stop, the white canyon bottom is Cedar Mesa Formation. The mesas above are Moenkopi Formation over Organ Rock shale with a cap of lower Chinle Formation. We are standing on the resistant upper surface of the Moenkopi Formation.

Behind us are mesas of younger formations.

The lower part of the mesa is Moenkopi, ending in a shelf corresponding to the surface Gary is walking across. Above is Chinle Formation, then massive cliffs of the Jurassic Wingate Sandstone. This is capped with thinner beds of the Kayenta Formation, another fluvial formation, and knobs of the Navajo Sandstone. The Navajo Sandstone is yet another dune sea formation, similar to the Cedar Mesa Formation but a hundred million years younger. That’s longer than the time interval separating the last of the non-avian dinosaurs from the modern political convention.

We continue past the feet of the Henry Mountains, where the road cuts through a rather pretty pediment gravel. The chief attraction is large hornblende crystals.

Gary and I grab some nice samples.

Hornblende is a black amphibole, a kind of silicate mineral in which the silicate forms long strands surrounded by metal ions. It is, alas, softer than the surrounding rock, and so cannot easily be polished out.

A view to the west from atop the pediment itself:

A pediment is a nearly horizontal fan of sediments eroded off a mountain face in an arid climate. Groundwater containing dissolved calcium rises to the surface and evaporates, so that calcite accumulating as caliche cements the surface and makes it resistant to erosion.

The beds to the north are labeled the Poison Spring Benches. To the west, beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation are exposed, then Dakota Sandstone forming a bench at the base of the mountains. The mountains themselves are diorite, a rock formed from magma with a moderate silica content that slowly solidifies underground. The rocks in the road cut with the large black hornblende crystals are diorite. Diorite consists mostly of plagioclase feldspar, with dark iron minerals being common. However, I’ve never seen the spectacular honblende needles found in these samples anywhere else.

Finding room for rocks in the car.

We stop in Hanksville and reprovision, getting (among other things) a spatula with which to flip pancakes and bacon and eggs. Then off to Capitol Reef.

The Morrison is a Jurassic formation, famed both for its pastel colors and its wealth of dinosaur fossils. We are probably looking here at the Salt Wash Member, with its layers of mudstone and sandstone.

Continuing west, we come to the slightly older Summerville Formation.

This formation is tidal flat deposits, forming distinctive very thin beds of mudstone and siltstone. In this location, there are beds and veins of beautifully crystallized gypsum. Gary takes samples.

We enter a syncline, where the beds warp downwards, so that we cross progressively younger formations. The road rises through the Morrison and Dakota Formations into the extensive and very thick Mancos Formation, laid down in the Western Interior Seaway around 80 million years ago. To the north is Factory Butte.

We see what looks like a dike to its east, and there is a good dirt road headed that way. We decide to explore.

Panorama of the area.

This is, incidentally, only the second really new area for me on this trip. Up to now the only road I’ve not been on before is the road from Mexican Hat to Natural Bridges, and that was in the dark.

Factory Butte, and North Cainesville Mesa to its left, are underlain by the Blue Gate Member of the Mancos Formation and capped with resistant Emery Sandstone Member.

Closer to Factory Butte.

The surrounding plateau, the Factory Bench, is largely underlain by the resistant Ferron Sandstone Member of the Mancos Shale.

Looking at the dike.

The snow-shrouded Henry Mountains to the south.

We continue north, and find a rough path to the dike.

Granted, the road was probably cut by ATVs and I’m in a Hyundai Santa Fe with only moderately high ground clearance and front-wheel drive. So long as the weather holds, the road should be okay; the Blue Gate Member tends to weather to flat, soft ground. With some trepidation, I drive to the base of the dike, park, and we head out.

It turns out there is no dike; this is purely an erosional remnant of the Blue Gate Member, left here who knows why. Perhaps some subtle difference in the sediments that made them slightly more resistant.

Gary leads me high up the sides of the monolith.

Gary hunts but finds no fossils. There is, however, an ash bed.

Or so I figure. Some eruption far upwind, from a volcano long ground into the dust.

View of Factory Butte from the top.

Gary is having a wonderful time.

So am I, for that matter.

Base of the butte.

It’s larger than it looks. It always is.

View south.

But the weather is continuing to deteriorate, and I do not want my car trapped in a sea of mud. We head back to the main road, but continue north a short distance just to see what’s there.

Some decidedly carbon-rich beds.

Had I but known, the road I am on is labeled as Coal Mine Road, and there is a branch about a mile down the road that passes an actual coal mine marked on the geologic map. But I didn’t have the map with me, we didn’t know that, and with the weather deteriorating, we stopped and explored here.

Ferron Member. The coal is consistent with this sandstone bed marking a regression-transgression sequence like that of the Mesaverde Formation back at the Hogback.

On the way out, we pull into a flat area with a sign, which turns out to list the restrictions on camping there. The surface is a nice exposure of the upper surface of the Ferron Member.

We head into Capitol Reef National Park, only to find that the campground is already full. Well. Last time I was here, the ranger said they never fill the campground. It turns out the area is swarming with German tourists; it is their vacation season. They are invariably quite pleasant when encountered on the trail, but they have filled all the reservable camp sites in southern Utah. They are joined by a few Chinese and some American tourists whose spring break coincides with Easter.

We head west, pausing atop Panorama Point where there is cell phone reception for Gary to call his wife. East is the Reef itself.

A prominent landmark is Ferns Nipple, eroded out of the Navajo Sandstone that caps the reef.

There are several such features scattered across southern Utah, including both of Mollies Nipple. Someone was getting lonely.

To the north are spectacular cliffs.

We’re looking at Moenkopi Formation capped with Shinarump Conglomerate of the Chinle Formation. Capitol Reef is a hogback similar to the Hogback bach near Farmington, where beds are draped over a deep fault so that older beds are exposed to the west.

We still have to find a camping site. There is BLM land further down the road where we can do dispersed camping. Curiously, just outside the park, there is a large area of level ground with a couple of outhouses, several campers and tents already set up, but no signage whatsoever. It doesn’t look like traditional dispersed camping. Gary’s theory was that the town fathers of Torrey wanted campers staying nearby. We pull in and find a spot.

Our camp is in the upper Moenkopi Formation.

We head into Torrey and find a Mexican restaurant. It is filled to the brim. We backtrack to a hotel restaurant which turns out to have good food and good service. By which I mean that the waitress is a cute blonde thing who is eager to please. Gary strikes up a conversation with the folks at the neighboring table; they are from Wyoming and know of some very nice fossil beds there. Turns out to be the Kemmerer beds, near Fossil Butte National Monument. The monument itself is off limits for fossil hunting, but there are several private quarries in the area. Filed for future reference. It wouldn’t be a long side trip from Bear Lake next time my family has a reunion there.

Back to the tent and we turn in for the night. Rain is softly pelting the tent as we drift to sleep.

Next: Hunter of trilobites

Pingback: Wanderlusting Mount Taylor, Day 2 | Wanderlusting the Jemez