A sedimental journey, day 4

Up at sunrise.

At left is Howell Peak, underlain by (among others) Cambrian Howell Formation.

Morning in Marjum Pass.

Gary does breakfast.

We pack up and start south for the pass. Along the way there is what looks a lot like a landfill. Gary is curious and persuades me to pull up.

It looks like a quarry, though a nearby sign identifies it as a community site, suggesting a borrow pit. We find it is excavated in a shale not unlike that at U-Dig. I will later find from the geologic map that this is indeed another outcrop of Wheeler Formation.

Our initial impression is that this outcrop is barren of fossils. Some are.

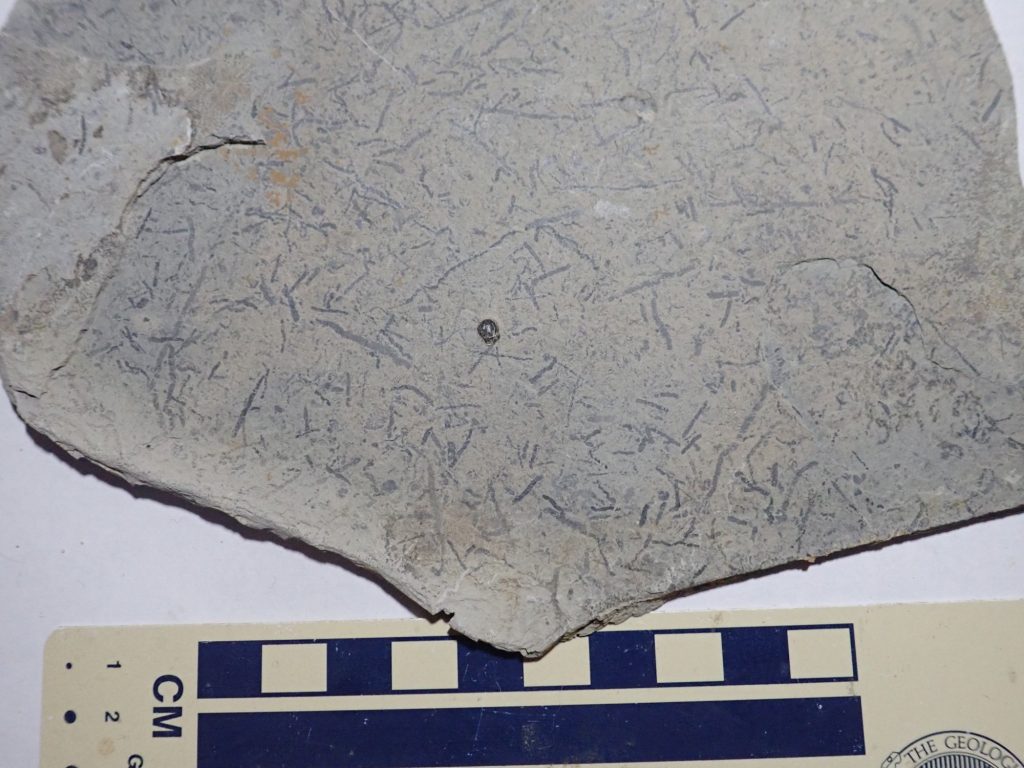

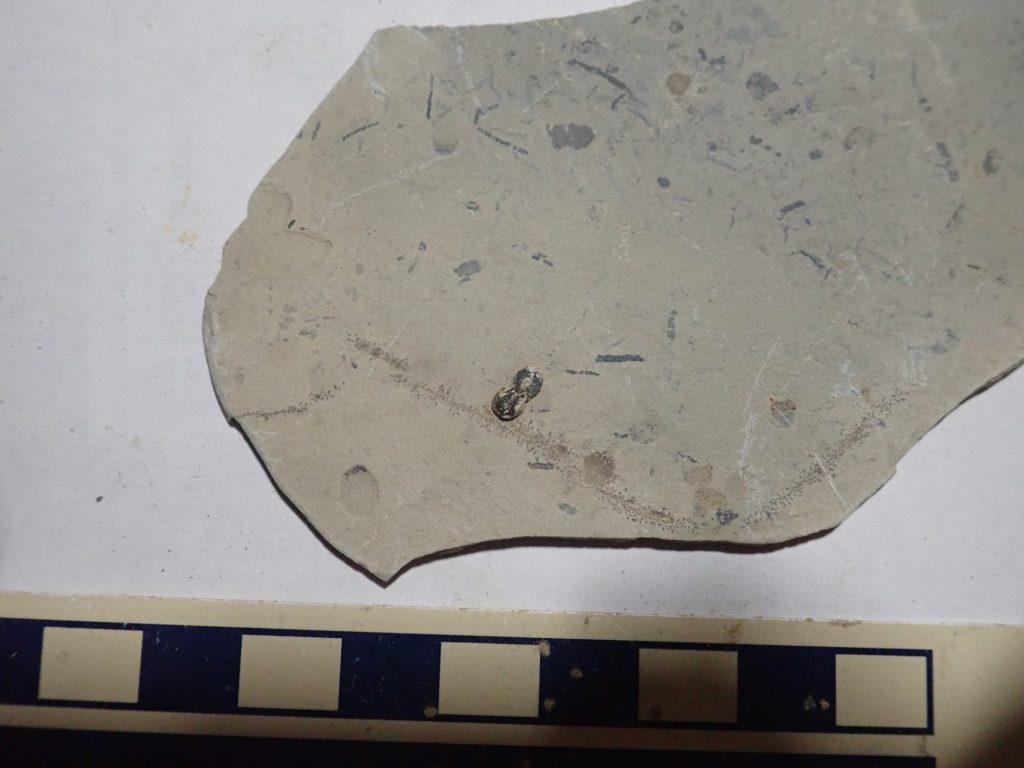

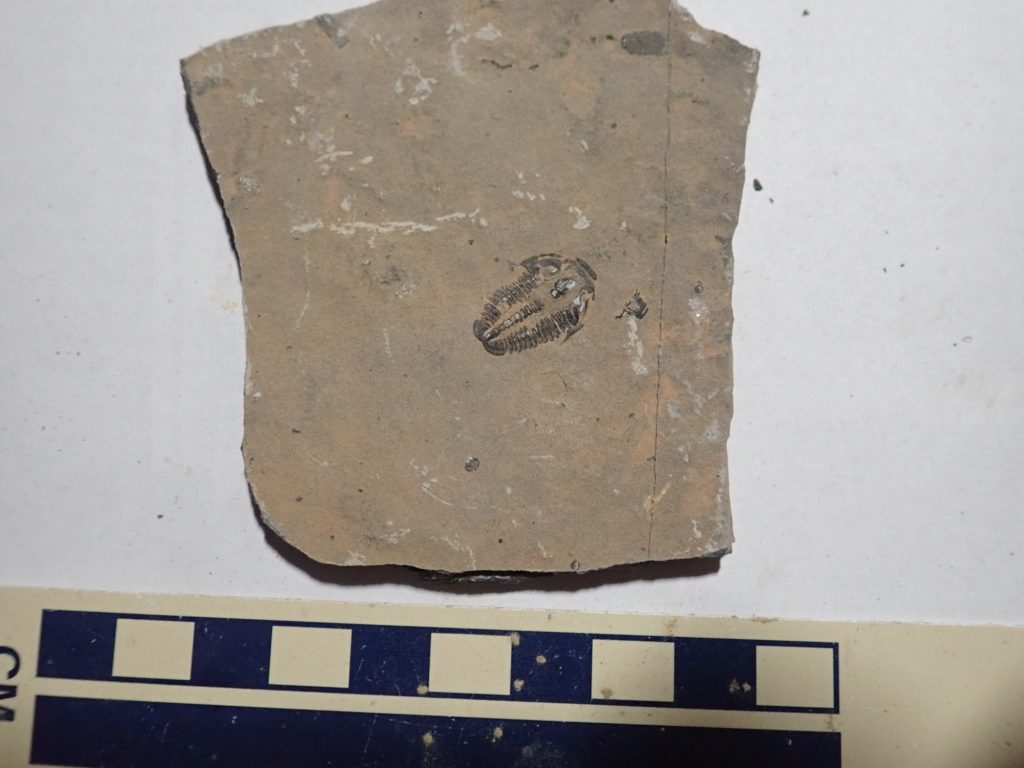

However, we eventually come across a spot where there are a scattering of agnostid trilobites, a variety that seemed very scarce at U-Dig. These are small eyeless trilobites with large cephalons and pygidia compared with their thoraxes.

The cephalon is the head region, while the pygidium is the tail region. Between is the multisegment thorax. Trilobites do not actually get their names from these three sections; they get their name from the three longitudinal sections, the left pleural, axial, and right pleural lobes.

And I once joked to Bruce Rabe, who is a nontheist, that agnostidism had been practiced for 540 million years. (He laughed politely.)

Gary is pleased with his find.

We continue south and reach the intersection of our road with Old 6 and 50 at the mouth of the pass.

The cliffs are capped with Weeks Limestone, atop Marjum Formation. Further into the pass, Wheeler Formation is exposed again.

We head on in, navigating by GPS to find the spot I found mentioned online.

And now for the stunning confession of this trip: When I get home and check GPS coordinates for this photograph, I find that we are a good 1160′ further along the road than we should be. We should be here. Could explain why our hunt was less immediately productive than I expected.

Which is not to say it was not productive. The first beds we come to seem barren at first, but they soon produce a scattering of agnostid trilobites. And the location of the beds relative to the road, and presence of agnostids, is consistent with the Google tip, so I remain firmly under the impression we’re at the right spot for the rest of the morning.

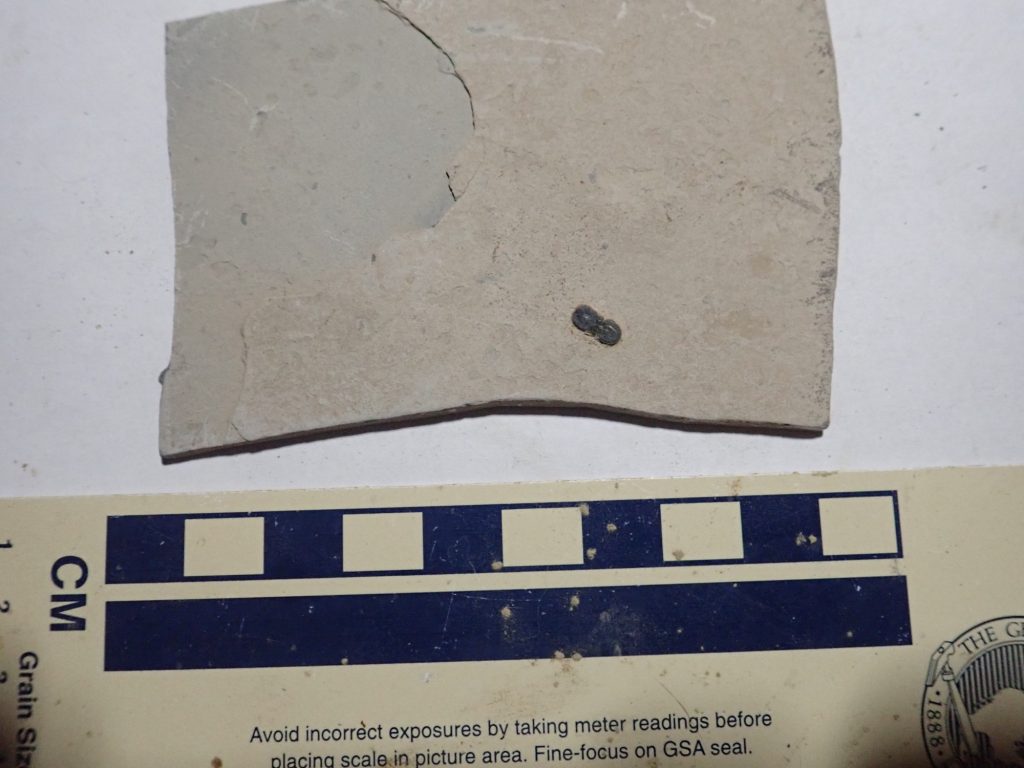

I suspect these are little buggy trails, with one bug.

We scramble atop the bank, and my attention is drawn by a red bed to the north.

It looks almost like a dike. I hike over.

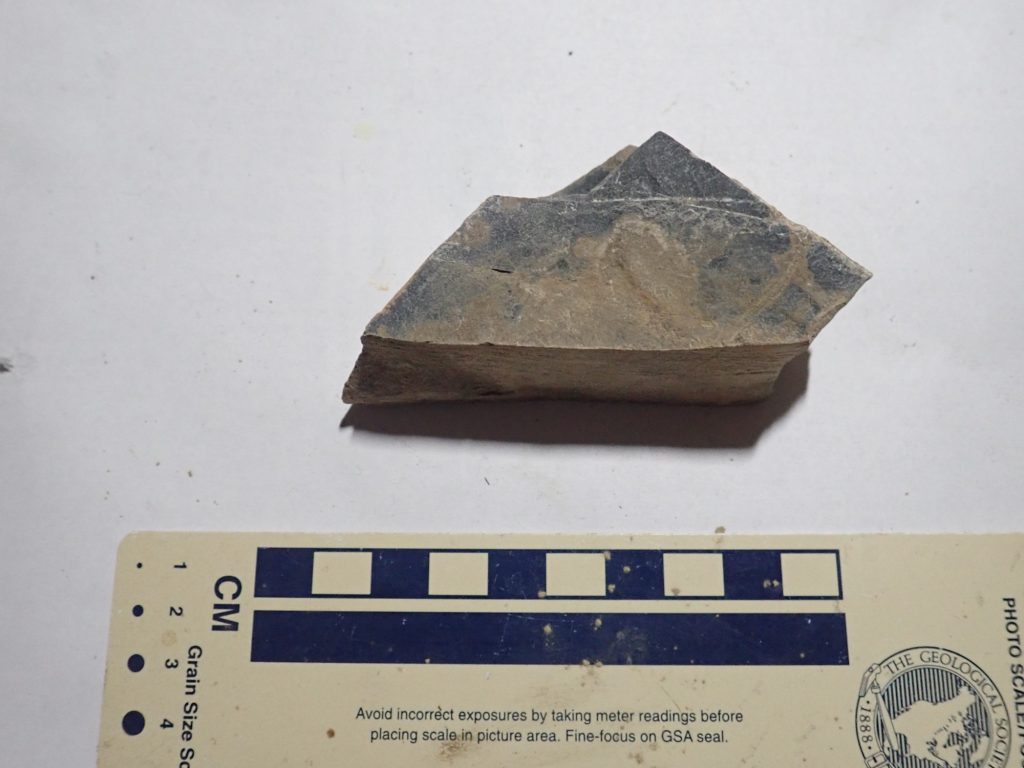

It’s a dense limestone that weathers red but is dark in fresh specimens. Had I but known, this is precisely the kind of bed that had the fossils at the correct location further north.

We walk some distance up the hill without spotting any fossils. There are, however, live critters.

Gary finds a slab that has what we hopefully think may be agnostids, once it is polished off.

I find a more myself.

This is the closest to a mortality plate.

View to the west through the pass.

The distant snow-covered peak is probably Mount Moriah, across the Nevada border.

Gary has found a couple of trilobite fragments.

But nothing else turns up. We continue climbing, and start to have some success.

We scout the area. So far as I can tell from my very crummy printed map, we are close to the right spot. Near here.

Or perhaps here.

It does look like someone has been digging furiously here, so I conclude that this is the spot from my Google tip, but that the area has been pretty thoroughly worked over for the best specimens. We do find some more but not a lot.

Of course, we’re nearly half a mile from the right location, due to my faulty navigation. But we don’t know this.

We continue to work the area and find the occasional trilobite.

This may be a fossil algae or bryozoan.

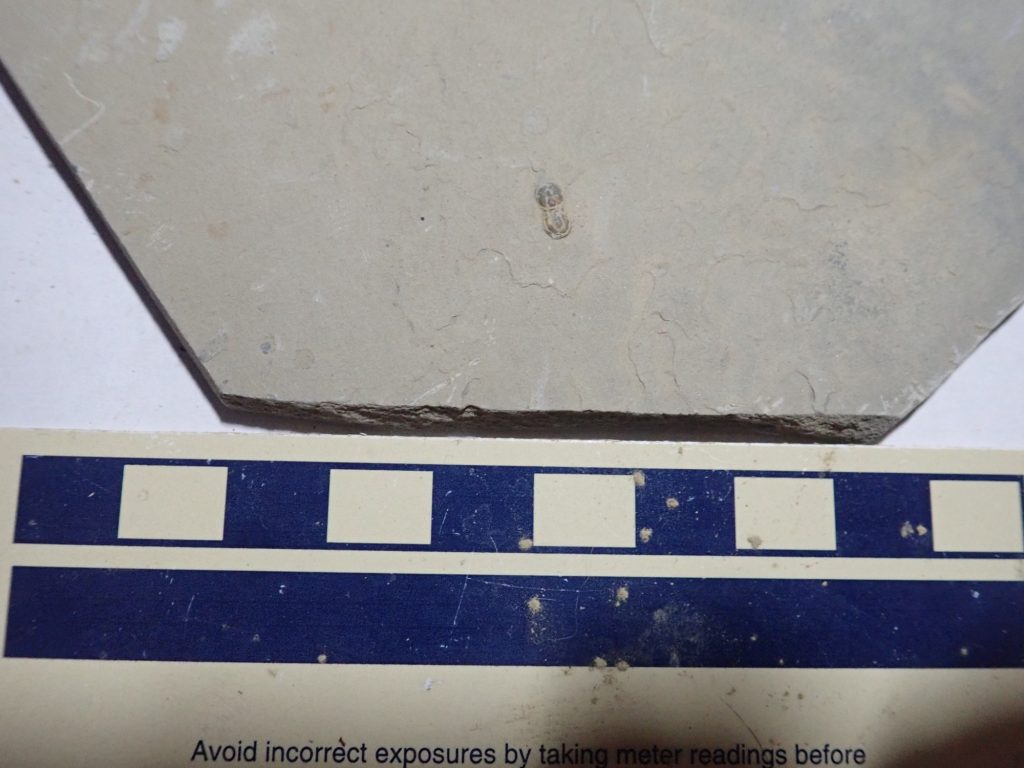

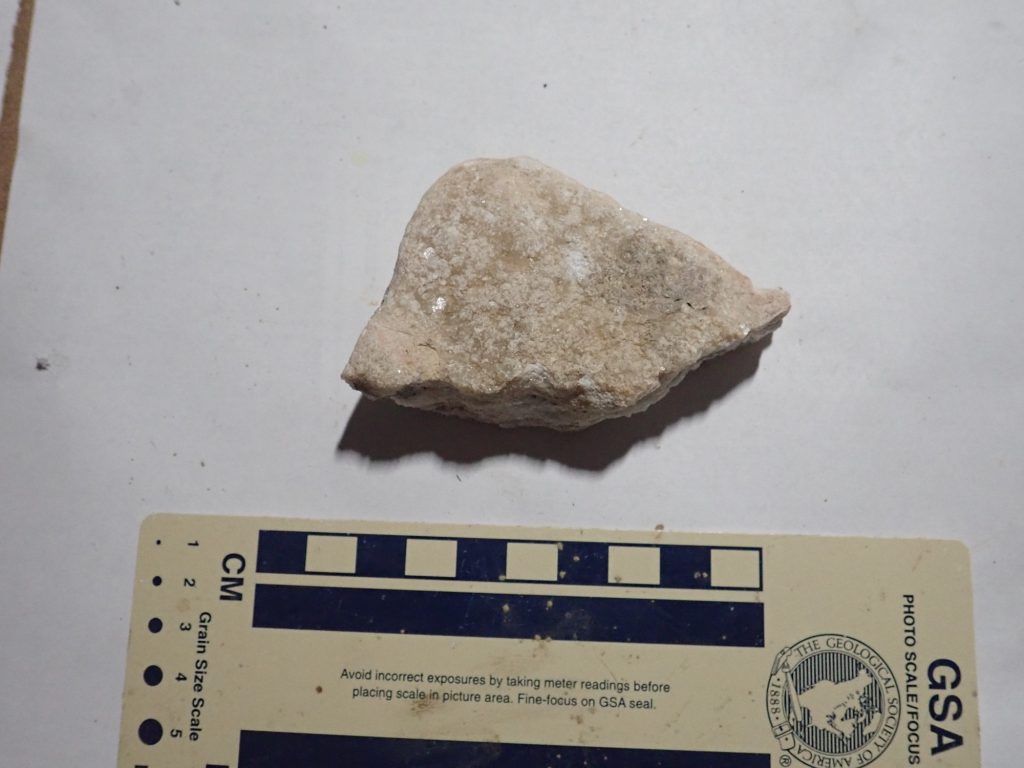

Coarsely crystalline limestone, probably from some higher bed.

This is I dunno.

The fossils here are clearly not the quality of those back at the U-Dig Quarry. They are, in fact, much more typical of the kinds of fossils one usually finds in a sedimentary formation. The Wheeler Shale at U-Dig and a few other localities in the House and Drum Ranges is a lagerstätte, or “storage place”, where unusual conditions have resulted in exceptionally good preservation of fossil remains.

Our time is up. We work our way back down the mountain to the car and depart, somewhat unimpressed with our finds. Though we did find some.

On the drive out: Sevier Lake.

The mountain ahead catches my attention.

Notice how the southern half of the mountain (to the right) is darker? It’s labeled Blue Mountain on the map; apparently I wasn’t the first to notice. The geologic map says the rock to the left is the Tintic Quartzite, a very prominent and widespread Cambrian formation in Utah that is indeed distinctively tan colored. The rock to the right is mapped simply as undivided Upper and Midde Cambrian carbonate rock. In other words, the geologists punted. The lazy ——-s.

Okay, in fairness, the geologists who mapped the area comment that the beds here are extraordinarily deformed. Probably picking out individual formations was just not easily done.

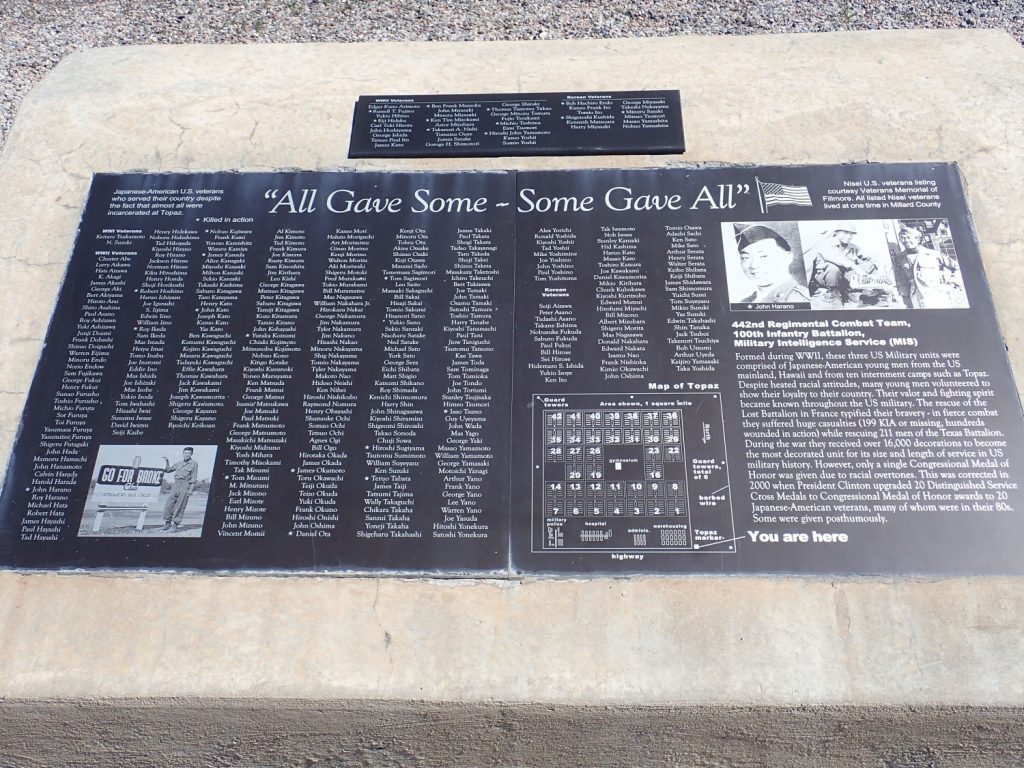

We drive through Delta and visit a site that ought to occasion some sober reflection: Topaz Relocation Camp.

Topaz is where some 9000 internees of Japanese ancestry were involuntarily relocated from the West Coast out of exaggerated fear for their loyalty following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The land was sold after the war and almost everything except the concrete building pads removed.

We arrive at the memorial, erected by the Japanese American Citizens League.

A fair number of internees enlisted in the military, particularly the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, which had an excellent combat record.

It was a shameful episode, but I found the memorial a bit off-putting. Look, I’ve written extensively about this here, and see no need to repeat myself.

We head for Provo, needing to be at the car rental before closing time so Gary can pick up his car. We do pause for some geology, like the lake deltas northwest of Delta:

The low beds at the base of the Gilson Mountains to the north (at left) are delta deposits of the Sevier River where it entered Lake Bonneville. The small knoll is underlain by Precambrian Caddy Canyon Quartzite, basement rock that has been strongly metamorphosed. The more distant mountains are underlain by various Mississippian limestone formations. The knoll at right, just before the valley through which we will be passing, is separated from the rest of the range by a large fault and is underlain by more Caddy Canyon Quartzite.

Right of the highway, the colorful beds

are Neoproterozoic (late Precambrian) Mutual Formation, overlain by lighter Cambrian Prospect Mountain Quartzite, The nearer knoll that is almost a dark purple in color is more Caddy Canyon Quartzite.

The rest of the range to the south is Prospect Mountain Quartzite over Mutual Formation.

The Neoproterozoic is the time interval just before the Cambrian. That would make these contemporary with the Grand Canyon Supergroup found towards the bottom of Grand Canyon. These may be sand deposited during the breakup of Pannotia, the supercontinent that preceded Pangaea.

In the pass, we encounter tuff and stop to look.

It is heavily vandalized.

This is the Fernow Quartz Latite, a welded tuff from the Oligocene flareup. The source was a caldera in the Tintic Mountains to the north, which was an important mining district a century ago. I point out some fiamme to Gary; these are bands caused when solid rock caught up in the very hot pyroclastic flow softened and was squashed flat, and they are diagnostic of a welded tuff.

Mount Nebo ahead.

This is the highest point in the Wasatch Range, at 11,933 feet. Most of the mountain is underlain by the Pennsylvanian Oquirrh Formation overlying Mississippian limestones. This is pretty much the pattern all along the Wasatch range as far as Mount Timpanogos.

A view of the mountains south of Nebo.

The hill at left is more unusual than it looks. It is Arapien Shale, a Middle Jurassic formation, that has been domed upwards by underlying salt beds. This is almost certainly the same formation we saw in the poorly mapped area around Brine Creek on Wednesday. Its evaporite beds have been exploited since pioneer times.

The mountain behind, San Pitch Mountain (as near as I can read from a confused topographic map) is the first range of Utah’s spine south of the Wasatch. It is underlain by the Cretaceous Indianola Group, which includes the Red Cliffs visible on the north side of the mountain.

From there we proceed to Orem. We are following directions given us by Gary’s digital assistant, Siri. Siri carefully guides us to the wrong location, and by the time we realize the car rental is miles south and head that way, the place is closed. Gary comes with me to my mother’s place and waits for his niece to pick him up while I pull his stuff out of the car, put everything in Mom’s garage that we won’t need until the return trip, and settle in.

Mom takes me to Olive Garden. I’m not terribly impressed; Olive Garden strikes me as a fast food place with pretensions of being a real restaurant. But the shrimp and chicken carbonara is quite tasty even if it’s not terribly healthy for me. (Perhaps because it is not terribly healthy? …)

My mother and I turn in early, because we have a long drive the next day to my nephew’s wedding.

Next: A reversal of tradition