Wanderlusting Guaje Mountain

I’ve explored the Pajarito Trail north of Rendija Canyon a couple of times before. However, I was looking for a not too long hike today, the weather was absolutely cloudless, I have not actually hiked to the top of Guaje Mountain before, and it seemed like a perfect day to hike to the top and get some panoramas.

So after completing few morning chores, I grabbed my pack and gear and headed up to the trail head.

I hiked quickly along the first part of the trail, since it’s familiar ground. But the dry stream bed at the bottom of Rendija Canyon continues to impress me.

It’s the gravel filling the dry stream bed. It’s extremely well-sorted but angular Tschicoma Formation, which is indeed the dominant formation upstream. Tschicoma Formation is composed mostly of dacite, a volcanic rock moderately high in silica, which was erupted west of Los Alamos between 7 and 2.5 million years ago. The Sierra de los Valles, the mountains west of Los Alamos, are all underlain by Tschicoma Formation dacite, and Guaje Mountain is part of a large Tschicoma Formation flow.

It’s a beautiful spring day and the wildflowers are in bloom. Los Alamos is between the Upper Sonoran and Transition life zones, meaning it’s at the upper altitude limit of the high desert. We had an unusually wet and cold winter (which we like)\, but, even in a normal year, spring is a time of rapid growth for many plants. They draw on winter moisture in the soil, struggling to set seed before the early summer drought spell sets in. This lasts until mid-July or so, when the summer monsoon brings the bulk of our annual moisture (15″ in a good year), and we get a second burst of wildflowers in the late summer and early autumn.

So there are going to be lots of wildflowers in today’s post. The first is a penstemon:

Possibly Penstemon strictus, Rocky Mountain penstemon, though the flowers are not quite deep enough blue.

I come into view of Cabra Canyon.

Click to embiggen, as you can do with most images at this site. At center right is Guaje Peak, underlain by Tschicoma Formation 3 million years old, the oldest formation you can see in this panorama. At far left is Beanfield Mesa, underlain by Tsherige Member, Bandelier Tuff, an ignimbrite erupted from the Valles caldera 1.25 million years ago. An ignimbrite forms when high-silica lava with much dissolved gas, which is extremely viscous, comes to the surface and disintegrates into shards of volcanic glass suspended in red-hot gas. This heavy mixture flows across the surface like a liquid, filling low areas and settling to the surface to harden into solid rock.

More Tsherige Member is visible across the canyon at left and on the flanks of Guaje Peak at far right.

The low ground is mostly Cerro Toledo Formation, which was deposited between the time of the Valles eruption and the preceding Toledo eruption at 1.62 million years ago. The Toledo Eruption produced a caldera that was nearly coincident with the younger Valles caldera.

Closer view of Guaje Peak.

The peak is vaguely “L”-shaped, with the upstroke running north/south and the base running to the east. We are looking at the corner of the “L” here.

Mustard.

Something in the mustard family, I think. Possibly western wallflower.

Daisies.

Exact species is difficult; there are bazillions of possibilities. The Compositae, aster family, is one of the largest in the plant kingdom.

North face of Beanfield Mesa.

This is a pretty typical finger mesa of the Los Alamos area. These mesas are all underlain by Tsherige Member, and you can see the multiple pyroclastic flows making up this unit. There are at least three here: A, B, C, and D in one mapping system, Qbt1g, Qbt1v, Qbt2 and Qbt3 in another. Um, three? A and B (1g ande 1v) may be a single flow; geologists haven’t sorted that out yet.

Thistle and yucca.

New Mexico thistle seems like a good guess. Yucca intermedia, possibly, for the other.

Oenothera.

Evening primrose. The pumice-rich soil is derived from the Cerro Toledo Formation.

I arrive at the rim of Guaje Canyon.

Both rims of the canyon are capped with Tsherige Member. Below are darker slopes of Puye Formation, rubble eroded from the Tschicoma Formation shortly after its eruption.

Here the trail branch to the summit is rather obscure.

Yeah, the first part is up that rock face. Fortunately I’m wearing a knee brace for my weak right knee. And here I enter onto new ground for me. Fortunately, the trail becomes much more distinct about 20′ up.

The trail turns south, and Guaje Peak is ahead.

There are wonderful views in all directions. I decide to take my panoramas on the way back down, after I’ve seen all the possibilities.

The summit area, halfway along the upright of the “L”:

Note the banding in the Tshicoma Formation. This is consistent with this being near the top of the lava flow, where the cooled lava would have begun to form shear bands as it solidified.

And a survey marker.

Curiously, there’s no elevation (it’s about 7610′). But the date is 1936.

It’s already clear I won’t get a good 360 panorama. This spot is as good as any for a panorama to the west.

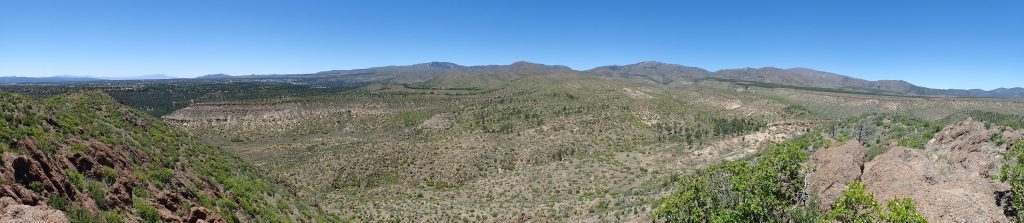

The panorama begins looking almost directly south, towards Sandia Crest on the distant skyline. To its right on the nearer skyline are the San Miguel Mountains, an outlier range of the Jemez, which were a cluster of volcanoes eight to ten million years ago. In front of them is the Pajarito Plateau and the city of Los Alamos. Extending across the panorama on the skyline is the Sierra de los Valles, the eastern rim of the Valles caldera.

The Tschicoma Formations beds here are sharply tilted.

The steep west face of Guaje Mountain is a fault escarpment, with the Guaje Fault at its base. This north-south fault is part of the eastern boundary of the Diamond Drive Graben, a low area at the foot of the Sierra de los Valles where the rock beds have dropped significantly.

Hullo, there’s a second marker nearby:

This one has no date, but my guess is it was installed the same time as the other, and shows the surveyed direction to true north.

A little further on, the trail turns east, but there is a rock cairn.

There is no obvious trail beyond, but I took this to mark the best place to leave the trail if you wished to bushwack south to the elbow of the “L”. It certainly turned out to be the best path.

Panorama to the south from the L:

The panorama starts directly east, towards the Sangre de Cristo Mountains and the valley of the Rio Grande. Round Mountain is visible in the distance in the valley.

I start back.

Panorama to the north.

Northern Sierra de los Valles at left, with Tschicoma Mountain just peeking over the ridge. At left center is Clara Peak, and at right is the Sangre de Cristo.

Barrel cactus.

They’re just starting to come into bloom. Prickly pear will come later, with rather unspectacular yellowish-green blossoms.

Yucca in full bloom.

Lupine. These are also just coming into bloom.

One final photo, of the west face of Guaje Mountain, which is the fault escarpment.

And back to the car.

It’s a four-day weekend for me. I will get in at least one, possibly two, more hikes. Tomorrow for sure is a fossil hunt near Taos. Monday depends on the availability of Gary Stradling; if he’s available, it will be an obsidian hunt; otherwise, I plan a long hike from the ski hill in Los Alamos to the north, towards Shell Mountain.