90th Birthday Wanderlust, Day 4: Needles District

I awake to another beautiful morning. I have some breakfast, fuel up again in Monticello, and head for the Needles district. I’m still playing it cautious, choosing the main route rather than a shortcut through the Abajo Mountains. But it’s a lovely drive either way, though I’ve driven the main route before.

I arrive at the visitor’s center and find the rangers outside with masks. The museum is closed, but fortunately the restrooms are open. I get in line to talk to the rangers, who are giving advice on hiking choices. My plan is to hike the Confluence Trail, but it’s a good 10 miles and the route look daunting on Google Maps. My backup is the Elephant Hill trail. However, after talking with the ranger, I feel more confident that I’m up to the Confluence Trail.

I drive to the trail head and saddle up. I’ve got a good day pack into which I load a trail lunch, can of Coke (for my headaches), and four pints of water. I slather on sunscreen and activate my SPOT satellite tracker. As I prepare to head out, a fellow waves me over. “See that young couple? I don’t think they know what they’re doing.” They are having trouble finding the start of the trail; it helps me that I checked it out first on Google Maps. It’s not completely obvious. But they also have no experience with hiking trails marked with cairns. I give them a quick education (a cairn is an obvious pile of stones that marks the correct path) and they are all right after that. (I meet them again at the end of the trail.)

The trail descends at once into a small canyon.

At this point the trail is lined with stones, so it’s not hard to pick out. It is, however, occasionally steep. Much of the trail is obvious, but where it crosses rocky ridges and becomes faint, there is abundant cairnage to show the way. The rock beds here all belong to the Cedar Mesa Formation, which we saw yesterday at its type location on Cedar Mesa. This is a Permian sandstone formation, formed from sand that was carried west by rivers, deposited along the shoreline (which was then in western Utah), then blown back east by the wind — over and over, sorting and polishing the grains to produce a very pure sandstone. This will be the only formation we see for most of the hike.

There is a scramble up a rocky ridge, and then a view of Island in the Sky district to the north.

The distant butte at left is Junction Butte. The plateau to its right is Island in the Sky. Both are well worth visiting, and I have done so several times. But they are not on the agenda for this trip.

This is the only spot where the Park Service had to put in a ladder to make a passable trail over a rocky ridge.

There are some scrambles in other spots, but obviously within the ability of a reasonably fit 59-year-old. Generally speaking, the first mile of the trail turned out to be the most rugged, and the last half mile the next most rugged. But I am getting ahead of myself.

Here we are past rocky ridges, for the moment, and hiking colorful flats.

The trail is reasonably clear. Anywhere there is any ambiguity about which way to go, the Park Service has placed a cairn to show the right way. There is really not much danger of getting lost so long as you pay attention to the cairns.

For my friend Dorothy Stradling: Cryptobiotic soil!

The crust is actually living, composed of cyanobacteria and other microscopic organisms that form a film over the soil. The Park Service strongly discourages hikers from wandering off the trail, in part, because they will pound down these living communities, which then take a long time to recover.

A nice view of The Needles towards the southwest.

Much of the Arches/Canyonlands region is covered with sandstone beds that have been fractured into numerous parallel fins that often extend for miles. The direction of fracturing reflects local geologic structure. Here it is northeast to southwest and we’re looking almost directly along the fracture direction. Near Moab, the fractures are roughly east-west. At Arches National Park, they’re northwest to southeast. In each case, the fractures are perpendicular to the direction in which the Earth’s crust was being stretched.

Visiting the Needles is on the agenda for my next trip through this area.

The trail comes to a big rocky butte.

Alas, my camera chooses this moment to lose its GPS lock. Here, I think. The knoll us unnamed on my topographic map.

I arrive at Twin Valleys.

This is the northeasternmost of the grabens that characterize the Needle District close to the Colorado River. Here several miles of sandstone beds have slumped towards the river as it has dissolved out the salt beds of the Paradox Formation from beneath them. Deep faulting produces narrow valleys where the rock has dropped relative to either flank.

Getting close.

Here the hiking trail joins a broad jeep trail. We are now crossing Cyclone Canyon.

This is reckoned by geologists to be the youngest of the graben valleys, judging from the lack of any established drainage. I am tempted to hike south into the canyon, but I don’t know if my stamina will be up to it. I have a ten mile hike as it is. In retrospect, I wish I had explored just a little further south.

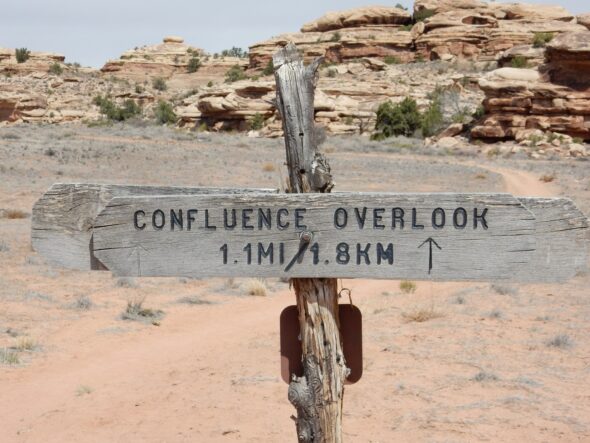

The jeep trail ends at a picnic area, then climbs a final rocky ridge to the confluence overlook.

Just right of center, the Green River coming in from the west joins the Colorado River flowing from north to south. You can see that the Colorado River is muddier, and the waters flow alongside each other for a time before mingling. I found that watching the slow eddies of brown water of the Colorado working their way out into the green waters of the Green River was relaxing, almost like watching clouds.

The cloud cover above is not ideal for photography, but it makes for a very pleasant cooler hike.

The light red beds forming the uppermost rims of the canyons are Cedar Mesa Formation. The somewhat darker beds below are lower Cutler Group beds. (The distinction is clearest at right, where the Cutler forms slopes under the vertical cliffs of the Cedar Mesa.) Below these are gray beds of the Honaker Trail Formation. We’ve seen all these formations earlier in the trip. However, the Cedar Mesa Formation is thinner here than at Cedar Mesa, and the lower Cutler beds contain more sandstone and less shale.

The young couple I met at the start of the trail catch up. I take a picture for them of the two of them against the stunning backdrop, using his camera. I then eat my trail lunch, rehydrate thoroughly with my can of Coke and a couple of pints of water with electrolyte tablets, and enjoy the scenery for a few more minutes, and then it’s time to head back.

Dramatic crossbedding in the Cedar Mesa Sandstone just east of the confluence.

Crossbedding is where a formation consists of larger beds which in turn consist of much smaller beds at an angle to the larger beds. It is characteristic of sediments laid down in a strong prevailing wind or water current — the former is much more common in this part of the world. The smaller beds dip in the direction towards which the wind was blowing.

Someone has decided to enhance a cairn.

More crossbedding.

In Cyclone Canyon, I meet a friendly ranger coming the other way. He confirms that I am, indeed, in Cyclone Canyon, and suggests a diversion south. I decide I’m already pushing my endurance.

Again, my GPS chose this moment not to lock.

Back in the grabens.

One of the natives.

Not a rattler, but he sure has his head puffed up to look like a venomous snake. Pacific gopher snake, perhaps.

Life endures in harsh environments.

Here the rock has a thick coat of desert varnish.

Desert varnish is a natural coating of iron and manganese oxides, possibly with trapped clay particles or silica.

I come within viewing range of the trailhead, where the Wandermobile waits patiently.

I am tired enough that I occasionally stumble. I remind myself to be extra careful here at the end, where the trail is probably at its worst.

The final stretch.

And then I’m done. I’m feeling pretty good. The water with electrolyte tablets, together with the can of Coke, seem to have really helped keep me from developing a headache. (I’m prone to headaches.)

On the drive back, a nice view of The Needles.

I turn briefly into the road to Elephant Trail trail head. Past the campground, the road is still nominally paved, but steep and poor. I pause for a final view of The Needles, then turn back.

I drop briefly by the visitor center. The ranger from my earlier visit tells me I look “happy tired.” It was a wonderful hike.

From there, back to Devils Campground. Gary Stradling has been trying to call; my cell phone was off to save power in areas with no tower coverage. We finally connect, and a few minutes later, his car slides into the space behind the Wandermobile at the campground. Gary sets up his hammock, then we drive down to Blanding to the burrito place. Then back to camp for the night.